CHAPTER 7

PSYCHOANALYTIC PSYCHOTHERAPY

The psychoanalytic approach began with Freud’s discovery of the unconscious and the use of free association at the end of the nineteenth century and blossomed in the mid-twentieth century. Psychoanalysis ushered in a new form of scientific inquiry that many consider as an intellectual milestone of the twentieth century and the birth of the modern study of the mind and self (Schwartz, 1999). Contemporary neuroscientists have found support for the neurobiological basis of many of Freud’s constructs (Ayan, 2006). “For the first half of the 1900s, Sigmund Freud’s explanations dominated views of how the mind works. [Freud’s] basic proposition was that our motivations remain largely hidden in our unconscious minds” (Solms, 2006, p. 28). Psychoanalysis gained credence and evolved into various branches and schools, each with its own perspective about the root cause (etiology) of psychopathology and its own approach to change. Almost all contemporary systems of psychotherapy have their roots in psychoanalysis and base many of their constructs and principles on the foundation that Freud laid out in his comprehensive metapsychology of mind, psychopathology, and psychotherapeutic techniques (Adler, 2006). According to Gabbard (2005):

Modern psychodynamic theory has often been viewed as a model that explains mental phenomena as the outgrowth of conflict. This conflict derives from powerful unconscious forces that seek expression and require constant monitoring from opposing forces to prevent their expression. These interacting forces may be conceptualized (with some overlap) as (a) a wish and a defense against the wish, (b) different intrapsychic agencies or “parts” with different priorities, or (c) an impulse in opposition to an internalized awareness of the demands of external reality. (pp. 3–4) This chapter presents an overview of the evolution and current state of contemporary psychoanalytic psychotherapy, also known as psychodynamic psychotherapy.

HISTORY OF PSYCHOANALYTIC PSYCHOTHERAPY AND ITS VARIATIONS

Beginnings of the Approach

The origins of psychoanalysis cannot be separated from the life, culture, and time of its founder Sigmund Freud (Gay, 1988). Freud is considered by many to be one of the most influential figures of the twentieth century (Millon, 2004) in the pantheon of individuals revolutionizing their fields, just as Darwin did for biological science and Einstein physics. According to Bischof (1970), “There is a unique parallel between the careers of Freud and of other intellectual giants. Freud, Darwin, Einstein, Dewey all pioneered certain aspects of their professional fields, [and] lived rather long certainly productive lives” (p. 31). Freud trained as a medical doctor and originally planned to be a neurologist. Freud’s early work focused on the scientific investigation of the workings of the nervous system, and he wrote numerous scientific papers on cellular foundations of the brain. Freud, “the would-be neuroscientist” (Hunt, 1993) desired to pursue a career as a researcher and professor but because of anti-Semitic attitudes prevalent at his time it was unlikely that he would advance in the European academic system, so he sought an alternative career path as a clinician. The financial pressure he felt after marrying resulted in establishing a private medical practice as a way to support his growing family.

One of the most commonplace and debilitating psychiatric disorders of Freud’s time was hysteria, which was typically treated with hypnosis or institutionalization in sanatoriums. The search for the etiology, classification, and treatment of this debilitating disorder was a major focus of clinical scientists of his time, most notably Charcot (1882) who pioneered the use of hypnosis and documented this disorder with newly developed photographic techniques. Freud’s daughter Anna also sought a career as a psychoanalyst and became an influential figure in the psychoanalytic movement and pioneering innovator of child analysis techniques. Carl Jung was the heir apparent to the Freudian legacy, but he fell out of favor after he developed his own theory of archetypes that emphasized the collective unconscious. The collective unconscious refers to memories that are carried from one generation to another.

Populations and Places Where Psychoanalysis Developed

Psychoanalysis emerged from a convergence of cultural, scientific, and historical events in Vienna where Freud lived and refined his theory and therapeutic approach, working primarily with patients suffering from hysteria. It is significant, therefore, to place Freud’s work in the context of time in which he developed his groundbreaking theory and treatment methods. Freud was raised in a rather repressive puritanical system that was the norm in post-Victorian society. He grew up in a culture where sexual expression, especially among the bourgeoisie, was highly restricted. Eastern European society had strong sanctions against expression of sexuality. Therefore, Freud’s life experience was not one that enjoyed open discussion, examination, or even recognition of human sexual expression (Gay, 1988). The members of society, mostly female, that tended to consult with him in his clinical practice, unduly suffered from these repressive forces in society. Freud’s notions about repression were not unknown to previous intellectuals and philosophers; however, his explication of this mechanism was central to understanding symptom formation and the basis of the talking cure that heralded contemporary psychotherapy. When society or an individual is under the force of severe repression, outbreaks of bottled-up impulses are expressed in disguised forms, both as a defense against and expression of the central conflict.

In his clinical practice, Freud was faced with many cases where it seemed apparent that the etiology of the patient’s symptoms and suffering had their origins in sexual trauma, often perpetrated by family members or caretakers. Originally, he posited that sexual traumata were the etiology of hysteria. Later, and much criticized by successive generations, Freud modified this seduction or trauma theory (Masson, 1984), developing a psychosexual theory that viewed these reports of childhood seduction as childhood fantasy or wish fulfillment. This is one of the central controversies of psychoanalysis that many believe led to a conspiracy of silence about the widespread prevalence and impact of child sexual abuse. Other psychoanalytic pioneers, most notably Sandor Ferenczi, were not so ready to eschew trauma theory in favor of a developmental psychosexual framework. This and other theoretical disagreements led to fractions between and division of Freud’s disciples, many who went on to evolve their own psychoanalytic theories.

In 1909, Freud was invited to the United States by the prominent psychologist Stanley Hall at Clark University. Accompanied by Carl Jung, Sandor Ferenczi, and Abraham Brill, Freud gave a series of lectures on psychoanalysis (Hunt, 1993) that introduced the theory of psychoanalysis to Northern America and set in motion a nascent movement that would later come to dominate American psychiatry and psychology, reaching ascendancy during the mid-twentieth century before falling out of favor when challenged by converging societal and scientific forces. Psychoanalysis found fertile soil in the emerging fields of psychiatry and psychology, both of which were ready for a theory with which to understand psychopathological adaptations and to guide those treating patients with mental illness. North America became a major force in disseminating psychoanalytic thought and in the establishment of psychoanalytic training institutes. The psychoanalytic movement was also fueled by the wave of psychoanalytic pioneers who fled Europe during the ascendancy of Nazi Germany with its persecution of Jewish intellectuals. Many of these psychoanalysts sought positions in North America and were extremely influential in training another generation of analysts and advancing psychoanalytic theory and practice.

Key Figures and Variations of Psychoanalysis

Psychoanalysis has generated many pioneering social scientists and clinicians far beyond the scope of this chapter to review. In his volume Masters of the Mind (2004), Millon identifies four seminal themes that distinguished Freud’s contribution to psychoanalysis:

(1) the structure and process of the unconscious, that is, the hidden intrapsychic world; (2) the key role of early childhood experiences in shaping personality development; (3) the distinctive methodology he created for the psychological treatment of mental disorders; and (4) the recognition that the patient’s character is central to understanding psychic symptomatology. (p. 262)

Freud’s metapsychology laid the groundwork for his disciples to use as a scaffold on which to delineate further the workings of the mind and methods of treatment. During the upheaval of World War II, many leading psychoanalysts (e.g., Melanie Klein and Anna Freud, along with her father) immigrated to England. Other key psychoanalytic figures (e.g., Franz Alexander, Karen Horney, Wilhelm Reich, Helene Deutsch, Heinz Hartmann, Otto Rank, Erik Erickson, and Heinz Kohut) immigrated to North America where their influence in theory development and practice remains highly influential.

Unfortunately, as with any intellectual movement, there was political strife and infighting amongst Freud’s disciples. The most notable and tragic casualty was Sandor Ferenczi (Rachman, 1997), one of Freud’s brilliant and creative followers and the founder of active therapy (now called short-term dynamic psychotherapy). He was an innovator in many techniques and methods of psychotherapy that are highlighted later in this chapter. Remaining committed to the centrality of trauma theory, Ferenczi died in professional exile, after having his papers suppressed in part because they challenged psychoanalytic dogma. Another innovative psychoanalyst was Wilhelm Reich, a well-respected European analyst who immigrated to North America and the pioneer of a psychoanalytic treatment known as character analysis. His classic volume Character Analysis (1945) advanced the understanding of treating previously refractory patients who suffered from what Reich described as character armor.

Many women were attracted to this new discipline and exerted a major influence on the theoretical and technical developments. Helene Deutsch, Karen Horney, Anna Freud, and Melanie Klein rejected much of the centrality of sex in Freud’s theory and instead emphasized maternal experience as central to shaping personality. They turned psychoanalysis “upside down” and a once “patriarchal and phallocentric” approach became “almost entirely mother-centered,” shifting from an emphasis on the past to the interpersonal (Sayers, 1991, p. 3). Their influence was broad and long lasting. They were innovators in developing forms of treatment and assessment methods for children. Although there are numerous psychoanalytic therapists who had a major impact on the field, some key figures are highlighted in the following sections.

The Interpersonalist—Harry Stack Sullivan

Rejecting Freud’s structural-drive theory and instinctual basis for psychoanalysis, Sullivan believed that interpersonal relationships are the foundation of personality and psychopathology. In The Interpersonal Theory of Psychiatry, Sullivan (1953) wrote that all needs are essentially interpersonal. Instead of viewing the micro-level of intrapsychic functioning as the main domain of concern, he widened his theoretical perspective to observe what transpires in or between dyadic relationships as opposed to within a person. This was a phenomenal advance for the time because the dyad was not emphasized. Until Sullivan’s explorations, the processes and terrain were not mapped. He believed that the psychoanalyst was not merely a detached objective observer of the psychotherapeutic process but a participant observer who shares in making meaning and thus mutually influences the process. This challenged the notion of the detached, objective observer who was not engaged emotionally with the therapeutic process, reshaping the therapist’s role as someone who becomes engaged in the process in a unique manner.

The Self Psychologist—Heinz Kohut

Another emigrated psychoanalyst, Kohut diverged from standard psychoanalytic conceptualizations, by developing a theory of the self that has particular application from those suffering from narcissistic disorders or disorders of the self. In The Analysis of the Self, Kohut (1971) described his clinical findings and theoretical system and suggested certain technical strategies for working with self-disordered patients who were generally beyond the reach of classic psychoanalytic technique.

The Short-Term Psychodynamicists—Habib Davanloo and David Malan

There were many pioneering psychoanalysts who believed that the length of treatment could be abbreviated with technical modifications. Beginning with Ferenczi, many others including Franz Alexander (Alexander & French, 1946) experimented and risked their careers in their pioneering efforts to shorten the length of treatment. Two key figures, whose work is highlighted later in this chapter, challenged the notion that psychodynamic psychotherapy necessarily had to be lengthy. Working separately, but later engaging in a productive collaboration, Davanloo (1978, 1980) in Montreal and Malan (1963, 1976, 1979) in England advanced the work of their most notable predecessors Franz Alexander (Alexander & French, 1946) and Sandor Ferenczi. Combining theoretical constructs depicted as triangular configurations, Malan (1963, 1976, 1979) mapped the process of psychodynamic psychotherapy and Davanloo (1980) advanced techniques and methods for accelerating the course of treatment, expanding the work of Ferenczi, Reich, and others.

The Severe Personality Disorder Systemizer—Otto Kernberg

Originally from South America, Kernberg has been one of the most prominent contemporary psychoanalytic theorist-clinicians. Kernberg (1975, 1984), and as a prolific writer he has added substantially to our understanding of severe personality pathology such as borderline and narcissistic personality disorders. Along with his associates, he developed transference-focused therapy, an approach to working with patients with borderline personality disorders (Clarkin, Yeomans, & Kernberg, 1999). Kernberg elaborated our understanding of the way in which the structural components of each individual can be arranged along a continuum (psychotic, borderline, and neurotic) and how at each level the uniqueness of a person’s personality is colored by the temperamental predispositions and character development.

The Child Therapists—Anna Freud and Melanie Klein

Professional rivals and innovators in the application of psychoanalytic methods to the treatment of children, Anna Freud and Melanie Klein were highly influential psychoanalysts. A. Freud not only pioneered treatment approaches for childhood disorders but also expanded her father’s conceptual system of ego defenses that she outlined in The Analysis of Defense (Sandler & Freud, 1985). Klein (1946) developed the concept of projective identification and explored the area of primitive emotional states that she identified as consisting of two primary positions: (1) depressive and (2) paranoid-schizoid. To understand projective identification, a person must first understand the concept of projection—the process in which thoughts and feelings outside of awareness are projected onto someone else. This mechanism is the basis for how projective tests operate. When a person views a cloud or an inkblot and is asked to imagine what it is, his or her unique perceptual processes interprets the stimuli, and thus the person projects him- or herself in the way makes meaning of the pattern. Projective identification goes a step farther in its action. In our interpersonal relationships, when someone projects onto another person (e.g., seeing him or her as “bad” or “unfeeling”) and this is unrelenting, the person may actually assume some features of the projection and began to act consistently with that projection. In essence, the projection is received and accepted by the other member of the dyad. This is an important mechanism that occurs in intensive psychotherapy, especially when treating individuals with self or personality disorders who tend to use this primitive defense. Klein’s concept of the schizoid position is one whereby the infant splits good from bad experiences with maternal attachment. The depressive position occurs when the infant recognizes the maternal attachment as a “whole object” and then has to deal with the anxiety that ensues from the fear of losing his or her mother. Both A. Freud and Klein, although child analysts, approached working with children from divergent perspectives. A. Freud’s style was more psychoeducational than Klein’s, who used techniques and methods of adult analysis such as interpretation.

Most Popular Currently Practiced Psychoanalytic Variants

These frameworks may be categorized in a range of ways according to theoretical differences, emphasis on various component systems of human functioning (Magnavita, 2005), and ways of conducting psychoanalysis can differentiate most approaches.

Structural-Drive Theory—Intrapsychic Perspective

In structural-drive theory, the psychodynamic psychotherapist conceptualizes symptoms as manifestations of unconscious drives and conflicts among intrapsychic agencies (id, ego, and superego). Conflicts between the desire for gratification and societal restraints, along with developmental and traumatic events, may emerge in symptoms and characterological patterns that are ways in which equilibrium is attempted. Later, ego psychology (Blanck & Blanck, 1974, 1979) added substantially to structural-drive theory by emphasizing the concept of defenses and how they are utilized. These traumata result in either structural problems (i.e., managing affect, maintaining a coherent sense of self, utilizing appropriate defenses) that indicate problems with internal regulatory systems or developmental deficits that are related to poorly organized integration in internal structural domains such as the affect system, the cognitive-perceptual system, and so forth. This approach is based on the structural model of the mind whereby forces generated by repressed traumata result in anxiety that cannot be effectively managed and result in neurotic adjustment or clinical syndromes such as eating disorders, depression, substance abuse, and so forth. Ego psychology, another important development in psychoanalysis, evolved from structural-drive theory and paid particular attention to ego mechanisms of defense. Anna Freud’s The Ego and Mechanisms of Defense (Freud, 1936/1966) described nine individual defenses explaining how they operate, offering clinicians a crucial tool for understanding how affect is regulated. Her original list, which has been elaborated by many others, includes:

Heinz Hartmann (1939/1958), along with others, made further contributions to ego psychology by elaborating the zones of functioning that were protected by effective defenses. These zones include cognition, perception, affective regulation, reality testing, and impulse control and are part of our ego-adaptive capacities. Currently, there are over 100 defenses that have been catalogued (Blackman, 2004). Defenses have adaptive value in that they are incorporated to help the individual survive. Some defenses are useful in moderation but extreme versions are maladaptive. Primitive defense generally indicates a low level of function. Modern psychodynamic psychotherapists carefully evaluate these functions when doing a comprehensive assessment.

Relational Psychoanalysis—Object Relations and Interpersonal Theory

Two popular variants of psychodynamic psychotherapy recognize the profound importance of early attachment experiences on the internal models of the individual. In these theoretical models, aggression does not emerge from biologically based instinctual organization but from a disruption of attachment relations. Object relational psychotherapists believe that the dyad must be studied to understand the individual; the essential dyad is the maternal-infant attachment system. In the relational approach, the quality of the psychotherapist and patient’s relationship is the essential vehicle of the healing process. Early attachment schema are represented and activated in relationships and the psychotherapist attempts to figure out what parts of the internalized parental objects are standing in the way of developmental processes and mature self-other relationships. There is accumulating evidence for this perspective summed up by Anderson and his associates (S. M. Anderson, Reznik, & Glassman, 2005): “We argue that the nature of the self is fundamentally interpersonal and relational, providing all people with a repertoire of relational selves grounded in the web of their important interpersonal relationships” (p. 467).

The interpersonal branch of the relational approach was pioneered by Harry Stack Sullivan (1953), and it emphasized the transactions that occur between individuals in dyadic configurations. The most basic needs are biological satisfaction and interpersonal security. Again, as in object relations, the relationship with the psychotherapist is the crucial agent in healing and the real relationship with the psychotherapist is often emphasized over the transference relationship. The centrality of the relational matrix increasingly guided Bowlby’s landmark work in attachment theory (Bowlby, 1969, 1973, 1980) and assumed an increasingly prominent place in contemporary psychoanalysis (Fonagy, 2001). Bowlby elaborated how the attachment system was vital to growth and development and how psychopathology can develop when attachment bonds are prematurely disrupted. Current empirical studies have demonstrated that there are four basic attachment styles: (1) secure, where the child experiences the security of a firm foundation; (2) insecure, where the child is anxious due to maternal insufficiency; (3) preoccupied, where the child is vigilant and ambivalent about maintaining a connection with an inconsistent parental figure; and (4) disorganized, where the infant behaves erratically often sending opposing messages at the same time, often due to neglect or abuse (Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters, & Wall, 1978). Accumulating evidence is demonstrating that the most robust curative factor for all types of psychotherapy is the therapeutic relationship (Norcross, 2002).

Self-Psychological Theory

Heinz Kohut (1971, 1977) and to some extent Carl Rogers (1951, 1961) founded self-psychology with an emphasis on the self of the patient as a functional unit. Primarily concerned with the treatment of narcissistic disorders, Kohut emphasized the centrality of cohesiveness of self-functions. Kohut eschewed drive theory with its focus on sexual and aggressive drives and emphasized the importance of mirroring and idealization of the parental attachment as significant to self-development. Opposed to the intrapsychic conflict model of the structural-drive approach, self-psychology emphasizes developmental defects. This suggests that psychopathology is related primarily to deficits rather than conflict. In self-psychology, the psychotherapist seeks to identify weakness and deficits within the self such as unstable self-esteem or impaired self-concept. Through the use of empathic attunement and mirroring, the psychotherapist seeks to provide a corrective emotional experience that allows the individual to develop more integrative self-functions and thus be less symptomatic.

Multiperspective Approach

Human beings are much too complex for any one perspective or narrow theoretical school to capture the phenomenology and uniqueness of the individual. Most contemporary psychodynamic psychotherapists utilize a multiperspective approach combining elements from structural-drive, ego psychology, object relations, and self-psychological theory (Pine, 1990). Thus, the psychoanalytic clinician views the patient’s patterns, personality configuration, and symptom constellations through multiple lenses to enhance understanding and facilitate treatment planning.

THEORY OF PERSONALITY AND PSYCHOPATHOLOGY

Key Aspects

The publication of Freud’s (1900) first work, The Interpretation of Dreams, “regarded as his magnum opus” (Goldenson, 1970, p. 348), was one of the most important psychological works of contemporary psychology. Although slow to take hold, Freud’s book gradually became iconic in its influence on our understanding of the human psyche and advancement of dynamic psychiatry. S. Freud’s (1966) essential technique of free association and conceptualization of the unconscious allowed him, and others who followed, to explore the dark recesses of the human psyche and to provide a map of the unconscious and psychological suffering. The concept of the unconscious refers to that which is out of conscious awareness. Current evidence from neuroscience supports the discovery that processing occurs at a subcortical or limbic part of the brain (i.e., emotional processing and memory consolidation). Freud found in his own analysis and with his patients that dreams are clues to the problems and passions of life. His discovery of and delineation of dreams, or condensations of both conscious and unconscious experience, are considered a window into unconscious processes. His technical advance was the discovery of free association, which allowed the analyst to have access to unconscious processes. Free association is a procedure by which the individual freely reports whatever comes into his or her head without censoring (as we all do in our daily lives). In this way, the analyst could interpret the fantasies, dreams, and musing of the patient. He outlined the topographical contours with his delineation of the unconscious, preconscious, and conscious zones. He proposed a tripartite model of the human psyche, with the three structural components that are now taught in every introductory psychology course: (1) the id, (2) the ego, and (3) the superego. Freud explained how the “instinctual” sexual and aggressive forces are modulated and channeled either neurotically into symptom formations or characterologically into personality disturbance. His emphasis on psychosexual development, much of which has not been empirically supported, represented one of the first attempts at developing a stage theory of human development. The key concepts of repression and resistance offered psychoanalysts a way to understand how unacceptable impulses and painful affects are lost to the conscious mind but are expressed in a variety of symbolic ways and how and why the patient resists attempts to achieve a cure. Repression is the process by which the conflicts that the person is unable to face, because of the painful associated affects, are essentially pushed down into the unconscious where they are expressed in derivative form such as slips of the tongue and symptom formations. Resistance refers to the patient’s use of defenses to keep the analyst from getting too close to the painful feelings associated with the trauma. Dealing with resistance is one of the major challenges for the analyst who must bypass these through free association and interpretation. Current-day psychotherapists of just about every ilk have incorporated the concept of repression into their theoretical system (Magnavita, 2002).

Freudian psychology has become so popularized that many of his constructs are engrained in contemporary language, shaping Western attitudes and culture. Viewing the basic structure of the mind, Freud described these three parts and their functions:

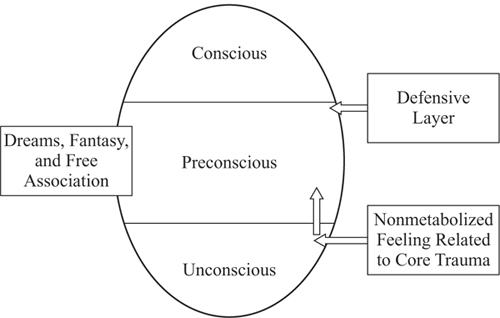

Topography of the Mind

Viewing the topography of the mental apparatus, we can further delineate the terrain depicted by Freud. The mind has three main subsystems or domains: (1) the unconscious, (2) the preconscious, and (3) the conscious. These zones reflect different levels of awareness of experience, self-knowledge, narrative memory, and ongoing mental processes (see Figure 7.1). The unconscious zone is the part of the psyche that is out of awareness. The preconscious is the zone where awareness is only partial and communicated in disguise, for example, what we remember dreaming or slips of the tongue. The conscious zone entails the realm of functioning where full awareness is experienced. The construct of the unconscious has been supported by experimental research in social cognition and neuroscience. Within the unconscious are embedded the relational schema or scripts that we use to navigate the relational world. S. M. Anderson et al. (2005) wrote, “In our view, research in the realm of the “new unconscious” has demonstrated that unconscious processes occur in everyday life” (p. 422). They summarize four main conclusions from their research:

The operational system for how these structural and topographic aspects of the mind work necessitates a brief review of some essential constructs. The first is anxiety that results from conflict in the aims of the mental agencies or when faced with external threat or threat to the integrity of the ego. In order for the system to operate and function adaptively, defenses are used to modulate anxiety so that it does not overwhelm the system. According to Blackman (2004), “Defenses are mental operations that remove components of unpleasurable affects from consciousness” (p. 1). These are organized at four primary levels: (1) psychotic (e.g., delusional projection, gross denial of reality), (2) immature or primitive defenses (e.g., projection, dissociation, idealization, withdrawal), (3) neurotic (e.g., repression, displacement, reaction formation, rationalization), and (4) mature (e.g., altruism, humor, suppression, anticipation, sublimation). Defenses may be used in a maladaptive or adaptive manner and can be called on in a crises or an emergency to allow us to survive and function under duress.

Therapeutic Elements

The therapeutic foundation on which all psychodynamic psychotherapy rests is the construct of transference. Gabbard (2005) writes: “The persistence of childhood patterns of mental organization in adult life implies that the past is repeating itself in the present” (p. 18). In essence, transference is our tendency to utilize internal relational schematic representations to orient our interactions with others. These internal cognitive-affective maps are used to navigate the challenges of the complex world by reducing incoming data and matching this with our internal template. The essential technique pioneered by Freud to access the internal schemata was free association, the window into unconscious process that psychoanalysis uses to begin to make interpretations between current behavior, transference patterns, and past experience. This process will bring to the conscious zone, the injuries and trauma that were suffered and the feelings that were repressed or split off from consciousness. Later, the concept of countertransference—the feelings aroused in the analyst as his or her unconscious takes in and responds to the patient’s transference—was elaborated. Various schools of psychoanalysis emphasized countertransference as a crucial aspect of the therapeutic process that informs the analyst about the nonmetabolized feelings and conflicts of the patient. In addition to the technical aspects of transference and countertransference, psychoanalysis also emphasizes the unique character formation of each individual.

Character or personality has a central place in psychodynamic theory and practice. Personality development is conceptualized by Freud as a biologically derived model in which the centrality of instinctual processes are emphasized and where humans pass through an orderly progression of bodily preoccupations from oral to anal to phallic and finally to genital concerns (McWilliams, 1994). Failure to navigate successfully through these stages could fixate the character and the conflicts of these periods would be embedded in the character structure of the individual.

Early psychodynamic clinicians and theorists were seminal in developing a deep understanding of the importance of personality function and adaptation. Personality is not a compilation of traits but a dynamic holistic system (Angyal, 1941). Carl Jung and Alfred Adler diverged from Freud over the primacy of sexual and aggressive instincts and instead emphasized the social aspects of human functioning. Jung emphasized the collective unconscious, which was previously mentioned. In addition to this diversion from Freud, he emphasized various personality attributes that individuals use to relate to their world. He popularized the terms extrovert and introvert and believed that there are four modes of adaptation or functioning: (1) thinking, (2) feeling, (3) sensation, and (4) intuition. These four would later be used as a foundation for the popular personality inventory, the Myers-Briggs. Yet another seminal figure who departed from Freud’s beliefs, Alfred Adler emphasized the tendency to counteract deficiencies through compensation. Compensating for feelings of inferiority was seen as a major motivation of individual functioning.

Contemporary psychodynamic theory does not rely on this conceptualization but instead views personality from more of an ego psychology perspective, whereby personality is shaped by the unique combination of dispositional, neurobiologically predisposed, and temperamental variations shaped by relational experiences, resulting in the best adaptation for the personality system. According to the Psychodynamic Diagnostic Manual (PDM, 2006), “Classification of personality patterns takes into account two areas: the person’s general location on a continuum from healthier to more disordered functioning, and the nature of the characteristic ways the individual organizes mental functioning and engages in the world” (p. 8).

Dynamic System in Operation

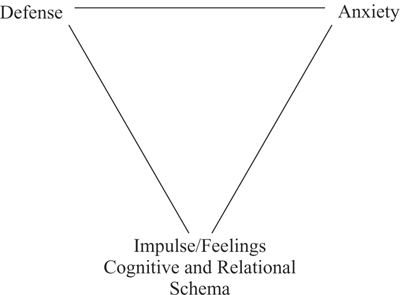

The conceptual system developed and refined by generations of psychodynamic psychotherapists can be represented by using two primary triangular configurations to depict the structure and process of psychotherapy. Termed by Malan as the Triangle of Conflict (see Figure 7.2), the first triangle can be depicted by domains and processes at three corners. At the bottom of the triangle, impulses and affect are represented. On the upper right side of the triangle, anxiety is located; and in the upper left-hand corner, defenses are placed. This triangular matrix depicts what occurs at the intrapsychic organization of the individual and this can be observed through the physiological reactions and defensive operations that are activated by intimacy and closeness with another person. This in turn activates the core relational schemata and any nonmetabolized feeling in relation to these people. As threatening situations, such as beginning psychotherapy are entered, underlying feeling related to attachment experiences give rise to anxiety that signals the individual that there is danger, either real or imagined, to the ego. This anxiety then is modulated by the unique constellation of defenses (depicted in the upper left-hand corner of Figure 7.2) that the individual has incorporated along the developmental path. If these are mature and adaptive, the individual can tolerate a certain amount of stress and maintain adequate ego functions. If their defenses are marginally functioning and at a lower level, such as primitive or neurotic, the individual might become symptomatic by developing clinical syndromes such as anxiety disorders, depression, relational disturbances, and so forth. Later, we discuss how this information is used in making an assessment of the patient.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>