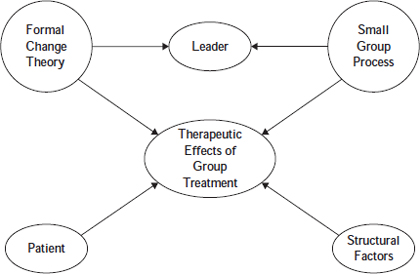

Chapter 11 A comprehensive definition of group psychotherapy includes groups that are used for the purpose of prevention, guidance, counseling, and training (Dagley, Gazda, Eppinger, & Stewart, 1994). However, group psychotherapy encompasses far more than simply a group functioning for a particular purpose. Fuhriman and Burlingame (2000a) defined group psychotherapy as “the treatment of emotional or psychological disorders or problems of adjustment through the medium of a group setting, the focal point being the interpersonal (social), intrapersonal (psychological), or behavioral change of the participating clients or group members” (p. 31). Group therapy does not spontaneously occur when several clients meet together with a therapist. Rather, a group therapist is conscious of group processes and dynamics and fosters member interactions that allow the group to function as the medium facilitating therapeutic change. Group psychotherapy provides several benefits. Perhaps the most obvious benefit is its resource efficiency. Clients receive treatment for a fraction of the cost devoted to individual sessions because group therapists typically treat 6 to 8 clients in a typical 90-minute session. Group psychotherapy’s resource efficiency, when compared to other treatment modalities, may be the reason its use has been predicted to continue on an upward trajectory for the foreseeable future. For instance, among clients using nationwide managed-care systems, group treatment was predicted to constitute nearly 40% of all patient visits over the next 10 years (Roller, 1997). Furthermore, Fuhriman and Burlingame (2001) found in their survey of directors of accredited mental health training programs (clinical, counseling and school psychology, psychiatry, and social work) that most believe the use of individual psychotherapy as a treatment modality will decrease, whereas that of group psychotherapy will increase. However, neither the cost-efficiency of a given treatment program nor its capacity for broad dissemination provide convincing evidence for its widespread use. As Davies, Burlingame, and Layne (2006) have queried, “Indeed, what is the social value of providing large numbers of people with efficient access to a watered-down treatment, as some theorists, and prospective patients, no doubt believe?” (p. 388). Fortunately, group psychotherapy is not only resource efficient, but it is also an efficacious treatment for a wide variety of disorders and disabilities (Burlingame, MacKenzie, & Strauss, 2004). Hence, it is “widely used in almost every treatment setting” (Fuhriman & Burlingame, 2001, p. 401). How can group psychotherapy be efficacious when each client in the group receives only a portion of the group’s time or the therapist’s attention? For the past several decades, proponents of group treatment have argued that the group processes and group dynamics that occur in the group are potent therapeutic forces that are additive beyond the change associated with specific protocols. Therapists who appreciate these group features view the “group as an entity larger than the sum of its individual members or the specific protocol used to guide treatment. These therapists acknowledge that the collective, interactive properties of the group have potent effects on members that extend well beyond interventions associated with the formal change theory” (Davies et al., 2006, p. 393). Therefore, although a formal change theory is often present, therapists rely on the group processes for therapeutic effects. This chapter continues a more thorough investigation into group psychotherapy. It begins with a brief look at the history of group psychotherapy, including its origins, development, and current status. It then discusses group psychotherapy’s “borrowed identity” (Burlingame et al., 2004), with an exploration on the theory and process of group psychotherapy, therapeutic factors, and strategies and interventions. Special issues that arise in group treatment, as well as group adaptations for specific populations are also discussed. We address the empirical support for the modality, and then highlight cognitive-behavioral group therapy, followed by a clinical example of its use in the treatment of depression. We end with a brief section on resources for training. Group psychotherapy does not have a clear beginning. The written history of groups in general only began at the end of the nineteenth century, and it appears to have originated from simultaneous efforts (Ruitenbeek, 1969). Therefore, to whom credit belongs for beginning the treatment modality is subject to conjecture (Dreikers 1969a, 1969b; Fuhriman & Burlingame, 1994; A. M. Horne & Rosenthal, 1997). Using the chronology of publications, the first contributor was Joseph Henry Pratt who began treating tuberculosis patients in a group “class” format (Pratt, 1969). Pratt attributed success to a patients’ identification with one another, hope of recovery, as well as faith in the class, methods, and physician (Fuhriman & Burlingame, 1994). Some time later, Pratt evolved his classes to a more psychotherapeutic approach that looked more like modern-day group psychotherapy. Some have argued for simultaneous efforts in the United States and Europe, but note that European efforts went unnoticed because they lacked formal publications (Dreikers, 1969a, 1969b). One European contributor, Jacob Moreno (1932), offered a theory of therapy based on interpersonal and group influence, spontaneous expression, and acting out (i.e., psychodrama). He was instrumental in helping group psychotherapy come of age by publishing the first book devoted to the subject in 1932 and applying the name group therapy (Moreno & Whitin, 1932). Moreno later came to America, in part, to introduce his ideas concerning “group” because previous group experiences only addressed the group members as individuals, whereas the new focus was on working with individuals in the context of the ensuing interactions. Freud (1921) is also considered a contributor to group psychotherapy. He held Wednesday night discussion groups with his students at 19 Berggasse Street in Vienna, Austria. Freud understood that the inclusion of others in therapy influenced the process of analysis; he considered the group as a whole producing its own dynamics and experiences. He emphasized the importance of the leader in group formation and group functioning; in our modern-day group work, the leader is known to be central to a group’s cohesion (Dies, 1994). Alfred Adler was using a group approach in his “child guidance centers” in Vienna in 1921. His theory viewed humans as social beings, primarily and exclusively (Dreikurs, 1969b). Humans were viewed as having a primary motivation to belong, as well as being goal-directed and willing contributors in their environments. This was known as the principle of social interest and was viewed as a prerequisite for social functioning, whereas a lack thereof was the cause of deficiency and social maladjustment. It is not surprising that group became, for Adler and his coworkers, a suitable setting to address the nature of problematic behavior and offer “corrective influences” in which people make efforts to relate to each other as equals and to solve their problems based on mutual respect (Dreikurs, 1969b). One of Adler’s coworkers, Rudolf Dreikurs began experiments with group treatment in 1923 and finally used what he termed collective therapy. Group psychotherapy has matured over the past 87 years, with several prominent individuals making significant contributions. In the 1920s, Trigant Burrow used a group modality in an intensive residential setting working with clients suffering from neurotic disorders. He credited self-disclosure, consensual validation, and a here-and-now focus as factors that facilitated change in his clients (Behr, 2004; Burrow, 1927, 1928; Galt, 1995; Hinshelwood, 2004). In the next decade (late 1930s), Louis Wender and Paul Schilder applied a psychoanalytic approach to psychotic, hospitalized adult patients in groups. They credited the re-creation of the family and universality as factors that facilitated change in their clients (Wender, 1936). Samuel Slavson (1943, 1962), who is considered by some to be the father of modern group therapy, worked mainly with children. He maintained an individual focus in the group, rather than focusing on group dynamics, and underscored the importance of transference for facilitating client change. More recently, prominent figures in the group literature are associated with particular models or patient populations. For example, Heimberg and associates have been a “dominant force” (Burlingame, Fuhriman, & Johnson, 2004, p. 653) in the treatment of social phobia developing and refining a cognitive-behavioral group therapy protocol that reduces social phobic anxiety, depression, and catastrophic cognitions in group members (Heimberg et al., 1990; Heimberg, Salzman, Holt, & Blendell, 1993). Piper is known for his contributions to brief group therapy (Piper & Ogrodniczuk, 2004) and more recently for his work with complicated grief (Piper, Joyce, McCallum, & Azim, 1993; Piper & Ogrodniczuk, 2004). This work is significant in the current zeitgeist of managed care where cost-efficiency is maximized and because of the progressiveness and comprehensiveness of the research program that not only showed that the treatment was effective, but also identified specific components of both the treatment and client presentation that predicted improvement (Burlingame et al., 2004). A final historical perspective lies within the theoretical models guiding group treatment protocols with four dominant models evident. Interpersonal group therapy, also known as “process-oriented” group therapy is “perhaps the most influential theoretical approach to group therapy” (Brabender, 2002, p. 319). It was developed by Harry Stack Sullivan, yet popularized by Yalom’s (1970) book The Theory and Practice of Group Psychotherapy, currently in its fifth edition (Yalom & Leszcz, 2005). Interpersonal group therapy was designed for long-term, open-ended, outpatient groups with a diagnostically heterogeneous membership that Yalom (1995) calls the “prototypic type of group therapy” (p. xii). One of the most important underlying assumptions of Yalom’s approach is that interpersonal interaction is crucial to the group therapy process; it is a catalyst for the development of therapeutic factors (discussed later in this chapter). In recent years, interpersonal group therapy has been applied to time-limited groups, inpatient groups, and diagnostically homogenous groups (Brabender, 2002). The core therapeutic premise is that disturbance in mental health and well-being finds its roots in interpersonal relationships, leading to the goal of improving a member’s capacity for meaningful relationships. The here-and-now process is the primary vehicle of change (Fuhriman & Burlingame, 1990) and events in the session take a higher priority than those occurring outside the group or in the distant past of the members (Yalom, 1995). In recent years, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) groups have become widely used in both clinical practice and research (Barlow, Burlingame, & Fuhriman, 2000). Cognitive-behavioral therapy groups are typically structured, manualized, short-term, problem-focused, and diagnostically homogenous (e.g., depression, eating disorders). Due to these characteristics, symptom relief and skill-acquisition are the main goals. Group members learn to recognize cognitive distortions and work to change maladaptive cognitive schemas through a variety of structured exercises such as role-playing, homework assignments, and bibliotherapy. Although members engage in a process of collaborative empiricism with the therapist and other members (Brabender, 2002), group dynamics tend to be marginally utilized in CBT groups (Burlingame, Fuhriman, & Mosier, 2003) in spite of their potential for increasing effectiveness (Fuhriman & Burlingame, 1994). Behavioral group therapy became popular in the 1970s as a cost-effective, time-limited treatment (Burlingame et al., 2003; Sundel & Sundel, 1985) that focused on modifying observable, measurable behaviors associated with a disorder (Gelder, 1997). The group format allows therapists to address problems in a testable conceptual framework (Burlingame et al., 2005). The social learning that occurs in groups through modeling and reinforcement of approximations to new behaviors has a crucial role in modifying maladaptive responses (Alonso, 2000). Different behavioral techniques, such as exposure and response prevention, are applied to specific clinical populations using time-limited models although long-term approaches also have been proposed (Belfer & Levendusky, 1985). Group psychotherapy does not have its own theory of personality and psychopathology. Indeed, Burlingame et al. (2004) note that most psychotherapy groups have a borrowed identity when it comes to formal change theory. This borrowed identity is often adopted from the theoretical orientation to which the group therapist subscribes. Yet, the collective properties of the group have effects on members that go beyond that of the formal change theory (Burlingame et al., 2004). Hyunnie and Wampold (2001) estimate that common factors may account for up to nine times more patient improvement (as measured by relative effect sizes) than the specific formal change theory used. This does not mean that a guiding formal theory of change is irrelevant. Burlingame et al. (2004) note that the formal theory of change (e.g., cognitive-behavioral, psychodynamic) is the most studied influence on therapeutic outcomes in group psychotherapy. Due to the pervasive influence a formal theory of change has throughout all stages of treatment—including assessment and diagnostic procedures, case conceptualization, the selection and use of specific therapeutic interventions, treatment monitoring strategies, and methods for evaluating treatment effectiveness or efficacy—its importance cannot be overstated. Indeed, a theory is needed to “explicate the mechanisms of change associated with ‘generic’ group processes that produce therapeutic effects of magnitudes that rival effects produced by formal theory-based groups and individual-based interventions irrespective of formal theoretical orientation” (Davies et al., 2006, p. 391). However, integration of such theories with theories of group processes can account for the latter’s added or interactive effects. This discussion brings to light a concern noted by Davies et al. (2006) that “the absence of a consensual theory or framework that effectively organizes the conceptual and empirical knowledge regarding group process or dynamic constructs is a major shortcoming in the field” (p. 391). Currently, researchers are attempting to remediate this limitation. There are several core assumptions about the group psychotherapy process: (a) the focus of the group is on each individual member’s change, (b) the group itself is the vehicle for change (i.e., the main mechanism of change), (c) interpersonal interaction is the medium through which change occurs, and (d) therapeutic factors occur within the group that facilitate the change process (Fuhriman & Burlingame, 2000a). With these assumptions, we have developed a framework of multiple therapeutic influences constituting elements of a general theory of group-specific mechanisms of action (Burlingame et al., 2004; see Figure 11.1). This framework begins with therapeutic outcomes of group treatment and asks the question: “What components of group treatment might explain observed [client] benefits?” (Burlingame et al., 2004, p. 648). The first major area used to answer this question is that of formal change theory, as has already been discussed. The second major area includes the principles of small group processes—the collective properties of the group that naturally emerge from the interactive nature of group treatment. The group leader represents the third area that governs the effectiveness of group psychotherapy because it is the leader that determines if the group is or is not “used as a vehicle of change to enhance the active ingredients of the formal change theory” (Burlingame et al., 2004, p. 649). The fourth area of the framework is the patient or client. Client characteristics, such as basic listening skills, have been found to influence psychotherapy outcome (Yalom, 1995). The last area in conceptualizing therapeutic outcomes is the group’s structural features, such as number and length of sessions, size, use of booster sessions, and so on. For instance, adding a booster session can increase the long-term effects of group psychotherapy (Burlingame et al., 2004). Group psychotherapy’s complexity becomes evident in this framework because each of these areas interrelates to influence therapeutic outcome in group members. Therapeutic factors have been examined for over half of a century. In the 1970s, researchers defined the possible mechanisms of change, or group processes, as curative factors (Bednar & Kaul, 1978; Parloff & Dies, 1977). These group processes have also come to be known as therapeutic factors; Bloch and Crouch (1985) have defined a therapeutic factor as “an element of group therapy that contributes to improvement in a patient’s condition and is a function of the actions of the group therapist, the other group members, and the patient himself” (p. 4); these elements may be intrapersonal or interpersonal. The most widely recognized therapeutic factors are from Yalom’s interactionally based theory (1970, 1995); due to their prominence in the group psychotherapy literature, they are outlined in Table 11.1. Another perspective on therapeutic factors is that of Bloch and Crouch (1985), which was derived atheoretically, allowing it to be applied to groups operating from a variety of theoretical approaches. The elements of their perspective include self-understanding, catharsis, self-disclosure, learning from interpersonal interaction, universality, acceptance, altruism, guidance, vicarious learning, and instillation of hope. It can be seen that there is some overlap between these two perspectives. Table 11.1 Yalom’s Therapeutic Factors

GROUP THERAPY

HISTORY OF GROUP PSYCHOTHERAPY

THEORY OF PERSONALITY AND PSYCHOPATHOLOGY

THEORY OF GROUP PSYCHOTHERAPY: HOW CHANGE OCCURS

Therapeutic Factors

| Instillation of hope: Members interact with each other though they are all at different points in their progress; this allows them to see others who have improved as a result of therapy. |

| Universality: Group members see others who may struggle with similar experiences or feelings, which disconfirms their feelings of uniqueness. |

| Imparting information: Imparting information is not unique to group but is of importance. |

| Altruism: Members receive therapeutic benefits through giving. Often group members will accept observations (gifts) from another member before accepting one from the leader. It is in this manner that members of the group act as an auxiliary therapist with members exchanging client and therapist roles with each other; this exchange process is believed to be growth promoting for both group members and the group as a whole (Fuhriman & Burlingame, 2000a). |

| Corrective recapitulation of the primary family group: The therapy group resembles a family; in the group, members interact with others and the leaders in ways similar to the way they once interacted with parents and siblings, which may help them resolve unfinished business. |

| Development of socializing techniques: This factor is also not unique to group but group (rather than individual treatment) may offer more opportunities for growth in this area. |

| Imitative behavior: Imitation is more diffuse than in individual therapy because members may model themselves on aspects of other group members, as well as the therapist. Vicarious or spectator therapy is important because group members learn from each other. “Even if imitative behavior is, in itself, short-lived, it may help to unfreeze an individual enough to experiment with new behavior, which in turn can launch an adaptive spiral” (Yalom, 1995, p. 16). |

| Interpersonal learning: Members may more readily point out group members’ roles in perpetuating their interpersonal difficulties. If they learn they have created their own social-relational world, then they realize they have the power to change it. |

| Group cohesiveness: Sharing affective experiences and the subsequent acceptance by others are strong factors in therapeutic outcome. |

| Catharsis: Cleansing is related to outcome, only if it is followed by some form of cognitive learning. |

| Existential factors: Group membership can more fully help members recognize the realities of life, such as life is not fair and bad things happen to good people. |

MacKenzie (1987) organized the therapeutic factors as supportive factors, learning factors, self-revelation factors, and psychological work factors. Supportive factors include universality, acceptance (cohesion), altruism, and hope. Learning factors include modeling, vicarious learning, guidance, and education. Self-revelation factors include self-disclosure and catharsis, whereas psychological work factors include interpersonal learning and insight. These therapeutic factors are differentially valued by outpatient, inpatient, and peer groups and Table 11.2 presents a quantitative summary of the most highly valued therapeutic factors in these settings.

Table 11.2 Quantitative Summary of the Most Highly Valued Therapeutic Factors

| Outpatient | Inpatient | Peer Groups |

| Catharsis | Altruism | Interpersonal learning |

| Cohesion | Cohesion | Insight |

| Insight | Universality | Altruism |

| Self-understanding | Insight | Cohesion |

| Universality | Hope | Catharsis |

| Interpersonal learning | Vicarious learning | Guidance |

| Self-disclosure | Guidance | Universality |

| Hope | Self-disclosure | Catharsis |

Therapeutic factors can be common to both individual and group psychotherapies or unique to group (Fuhriman & Burlingame, 1990). Those common to both modalities are those experienced intrapersonally (e.g., insight, catharsis), with the therapist (e.g., hope, disclosure), or with others (e.g., reality testing, identification). Therapeutic factors unique to group psychotherapy are those that are experienced only in the presence of others (e.g., vicarious learning, universality) or when engaged with others (e.g., altruism, family reenactment). Therefore, a therapist can enhance curative capabilities of group through the utilization of the interpersonal process. Holmes and Kivlighan (2000) experimentally examined these propositions and confirmed different therapeutic processes in group and individual treatments. Specifically, they found those therapeutic factors related to components of “relationship-climate and other-versus self-focus” are more prominent in group psychotherapy. Those therapeutic factors more common to individual treatment were those related to “emotional awareness-insight and problem-definition-change” (p. 482). Table 11.3 summarizes the interpersonal therapeutic factors unique to group and those common to individual treatment (Fuhriman & Burlingame, 1990; Holmes & Kivlighan, 2000).

Table 11.3 Enhancing the Therapeutic Quality of Group through Unique Interpersonal Factors

| Unique to Group | Common to Individual Treatment |

| Vicarious learning | Insight |

| Universality | Catharsis |

| Altruism-role flexibility | Hope |

| Cohesion—Social microcosm | Disclosure |

| Interpersonal learning | Guidance |

| Modeling | Education |

Goals of Group Psychotherapy

In group psychotherapy, the therapist chooses the goals of the group that are appropriate to the clinical situation, yet achievable in the available time frame (Vinogradov & Yalom, 1989). Key goals in group psychotherapy may be categorized into two camps: (1) attainable goals and (2) ideal goals. Attainable goals are typically viewed as those that help a client achieve the optimal level of functioning consistent with his or her financial resources, motivations, and ego capacities (e.g., symptomatic relief, skill acquisition, or social improvement). These attainable goals are only modifications of the ideal goal of personality maturation or characterological change (Yalom, 1995). However, Burlingame et al. (2004) indicate that attainable goals such as symptomatic relief may be the only appropriate goals for some groups. For example, a long-term group, such as a private practice clinic running a weekly interpersonal group for 2 years, has goals of both symptom relief and characterological change; yet, most time-limited groups are limited to symptomatic relief. An acute inpatient psychiatric unit has the goal of restoration of function because its duration may only last a few days to a few weeks (Vinogradov & Yalom, 1989). Indeed, Vinogradov and Yalom (1989) have indicated, “In time-limited, specialized groups, the goals must be specific, achievable, and tailored to the capacity and potential of the group members. Nothing so inevitably ensures the failure of a therapy group as the choice of inappropriate goals” (p. 33).

Assessment Procedures

Today’s climate in the mental health community has come to be known as the age of accountability because clinicians are often required to demonstrate the effectiveness of their mental health treatments to satisfy third-party payers, such as health care corporations (Lambert & Ogles, 2004). Therefore, it is recommended that group therapists use evidence-based assessment measures.

Group psychotherapy assessment involves the use of selection, process, and outcome measures. Selection measures identify clients who will most benefit from group psychotherapy. Building a group with members that can do the therapeutic work of the group is, in large measure, related to its success. Process measures track important aspects of the groups, such as group climate, therapeutic factors, quality of member interactions, and group cohesiveness. Outcome measures track individual group member change due to the therapeutic intervention; this can alert therapists to those clients for which no change or deterioration is occurring, allowing them to intervene before the member prematurely drops out of treatment.

In the 1980s, the American Group Psychotherapy Association (AGPA) sponsored the development and dissemination of a Clinical Outcome Results Evaluation (CORE) battery, a series of measures to assist in the evaluation of group-based therapeutic interventions. This battery has recently been revised and is called the CORE-R (Burlingame et al., 2006). It includes samples of handouts for group members, examples of group measures, and information regarding the measures. However, the AGPA does not necessarily endorse specific or individual measures, so clinicians are encouraged to select measures that best fit their specific needs. See Table 11.4 for a list of included measures.

Table 11.4 Group Assessment Measures from AGPA’s CORE-R Battery

| Pregroup preparation | Group Therapy Questionnaire (MacNair-Semands & Corazzini, 1998) |

| Group Selection Questionnaire (Cox, Burlingame, Davies, Gleave, & Barlow, 2004; Davies, Seaman, Burlingame, & Layne, 2002) | |

| Process measures | Working Alliance Inventory* (Horvath & Greenberg, 1989) |

| Empathy Scale (Persons & Burns, 1985) | |

| Group Climate Questionnaire-Short Form (MacKenzie, 1983) | |

| Therapeutic Factors Inventory Cohesiveness Scale (Lese & MacNair-Semands, 2000) | |

| Cohesion to the Therapist Scale (as needed basis) (Piper, Marrache, et al., 1983) | |

| Critical Incidents Questionnaire (as needed basis) (Bloch & Reibstein, 1979) | |

| Outcome measures | OQ-45: (Lambert, Burlingame, et al., 1996; Lambert, Hansen, et al., 1996) |

| Inventory of Interpersonal Problems (Horowitz, 1999) | |

| Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (Rosenberg, 1965) | |

| Group Evaluation Scale (Hess, 1996) | |

| Target Complaints (Battle, Imber, Hoehn-Saric, Nash, & Frank, 1966) |

*Recommended by AGPA CORE-R task force

The task force commented on the use of these measures as follows:

We envision the evidence-based group leader periodically taking the “pulse” of the group, being curious about group processes and being open to the possibility that measures of such may reveal “surprises” about differences in individual member experiences of the group-as-a-whole. The intent of using outcomes and process instruments is not to supplant clinical wisdom. Indeed, we see them as an adjunct to clinical experience and intuition. (Burlingame et al., 2005, p. 17)

To accomplish this view, the task force suggests an evidence-based group clinician periodically use process measures to assess constructs, such as the climate of the group and the ubiquitous therapeutic factor of cohesion, with at least one outcome measure to assess individual member change.

PROCESS OF PSYCHOTHERAPY

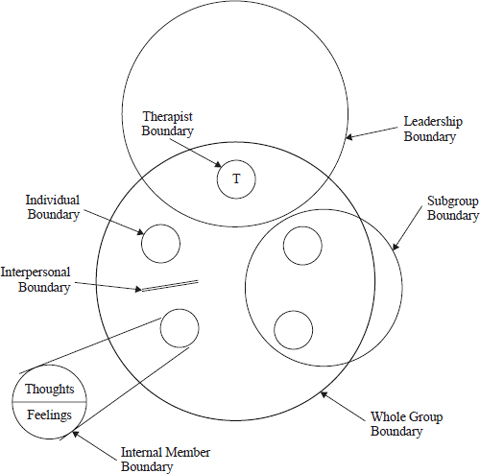

The process of group psychotherapy can be conceptualized from a structural perspective. At a high-level, relationships emerge from interaction at the member-to-member, member-to-leader, and member-to-group perspective. Greater complexity is added when two or more leaders are present. We (Burlingame et al., 2004) illustrated this complexity by considering the multiple boundaries evident in small groups as depicted in Figure 11.2, where the term boundary is used both in a physical sense (e.g., closing the door, where members sit) as well as an emotional sense due to the interactions of group members.

The whole group boundary recognizes the properties regarding the group as a dynamic, revolving entity, such as the number of group members or inclusion/exclusion criteria. The subgroup boundary recognizes the possible positive or negative impact clusters of group members may have on the group. The leadership boundary recognizes the theoretical model as well as the style used to deliver the treatment. The therapist boundary recognizes the impact a therapist may have on the group or some of the group members as a result of their personal characteristics (e.g., gender, age, personality). The interpersonal boundary recognizes the complexity of the relationships between the group members. The internal member boundary recognizes the internal processes of individual members, such as thoughts and feelings. As we have said elsewhere:

At any one time, individual, subgroup, and total group properties are operating. . . . At the same time, the focus may be on the interpersonal relationships as well as the psychological problems of individual members. Additionally, while the therapist, individual clients, and the group each has a singular influence, the interactive influence must also be considered. (Fuhriman & Burlingame, 1994, pp. 6–7)

These multiple boundaries can be considered according to two types of structure: (1) imposed and (2) emergent (Burlingame, Strauss, Johnson, & MacKenzie, in press). Imposed structure and process include those features of the group that the therapist does to the group, such as determining logistics, pregroup training, and leadership. Emergent structure and process include those features that naturally transpire during the therapy process (i.e., the therapist does not do it to the group), such as group development and feedback.

Imposed Structure

Logistics

Imposed structural principles begin with established logistics. Setting (e.g., outpatient, inpatient), duration (e.g., 60-, 90-, or 120-minute sessions), frequency (e.g., daily, weekly, bimonthly), total number of group sessions (e.g., 15, 30), and the degree to which the group is open to new members are important considerations. The physical location of the group is important. A secure (i.e., minimal interruptions), comfortable room that is available for the duration of the group is recommended. Seating should be fluid so that members can arrange chairs in a circular fashion to see one another and so the therapist does not occupy an attention-commanding position (Vinogradov & Yalom, 1989).

The typical duration of a group meeting is 90 minutes with a range of 60 to 120 minutes. Groups that contain lower functioning clients, such as you may find in inpatient settings, usually require shorter sessions of 45 to 60 minutes. The frequency of group psychotherapy meetings varies with most outpatient psychotherapy groups meeting once a week and inpatient groups meeting once a day or several times a week. Ultimately, the frequency of meetings depends on the clinical constraints and the therapeutic goals of the group (Vinogradov & Yalom, 1989). The question of establishing an open group (new members are added once the group has begun), a closed group (no new members are added once the group has begun), or a slow-open group (members leave and/or are added throughout the group treatment process) is also highly important to the success of a psychotherapy group. Inpatient groups are usually open, with high turnover rates for clients and therapists alike, whereas interpersonal groups are often closed so as not to disrupt the member interactions that mature over the course of the group (MacKenzie, 1994, 1997). Slow-open groups may be used in various ways, such as in primary care to make long-term group psychotherapy possible.

Size

Size of the group is a critical feature of imposed structure. Optimal size may vary slightly based on the purposes of the group; however, Dies (1994) indicates size is effective if it allows the group to interact, be compatible, and be responsive—including displaying high levels of empathy, acceptance, and openness. Converse trends that occur as group size increases include:

- Individual rates of interaction decrease.

- Infrequent contributions increase.

- There are more reports of threat and inhibition.

- Giving information and suggestions increase.

- Showing agreement decreases.

- There are more leader-directed statements.

- There are more frequent occurrences of the leader addressing the group as a whole (Dies, 1994).

- Showing agreement decreases.

Yalom’s (1995) suggestion for an interpersonally oriented interactional group is 7 or 8 group members, with no fewer than 5 and no more than 10 members. The lower limit is determined by the difficulties in having an interacting group when the number of clients drops too low; the upper limit is determined by the difficulties in having less time available for working through individual problems within the group processes as membership rises.

Pregroup Training

Like the intake process that occurs with individual therapy, group psychotherapy utilizes a pregroup training where the therapist meets with each group member in an individual meeting. In this meeting, assessment is combined with clinical efforts to prepare clients for group treatment. Assessment, such as using those measures in AGPA’s CORE-R battery, is vital to alerting therapists to someone who may be at risk for premature termination. Although group members are often not excluded from participation based on scores from these measures, a high score can alert the therapist to the importance of engaging the member in the group process. Clinically, a therapist’s main goal in this meeting is to present group as an effective and appropriate treatment. According to Dies (1993), most clients acknowledge group is as effective as individual but still express a preference for an individual format. Furthermore, clients can report negative expectations regarding group psychotherapy, such as fears of attack, embarrassment, emotional contagion, coercion, or actual harmful effects (Slocum, 1987; Subich & Coursol, 1985). Pregroup training reduces client apprehensions and instills positive role and outcome expectations.

Pregroup interventions are designed to provide a framework for clients to understand their individual experiences and events within the group context. Clients are educated about constructive interpersonal behaviors, helpful therapeutic factors, and group development issues (Dies, 1994). Particular information includes why groups are curative, why group therapy is the treatment of choice for the specific individual, what the therapist likes about group therapy, and an explanation of the responsibilities and time commitment the client is making.

Pregroup training can also be a method for determining the appropriateness of a client for group. According to Yalom (1995), frequently highlighted contraindications include the sociopathic client, the less psychologically minded client, the deviant client (in regards to their ability to participate in the group), and those that are likely to drop out due to external factors—such as those with long commute or scheduling conflicts. Yalom indicates that the therapist’s “expertise in the selection and the preparation of members will greatly influence the group’s fate” (p. 107).

Leadership

In regards to characteristics of the group therapist, warmth, openness, and empathy are as important as they are in individual therapy. Successful group leaders are also competent, trustful, and invested in the group process (Dies, 1994).

A group therapist is active, particularly in the early stages of the group’s development when group norms are established via “group interplay” (Fuhriman & Burlingame, 2000a, p. 32). Leadership style is very important in determining if the group is a vehicle of change by integrating formal change theory with small group processes, or if it becomes individual therapy with an audience (Burlingame et al., 2003; Yalom, 1995). Research has demonstrated that once norms have been established they persist for the life of the group and are resistant to change (Bond, 1983; Jacobs & Campbell, 1961; Lieberman, 1989). The responsibility for creating healthy norms falls primarily on the therapist (Davies et al., 2006). Yalom (1995) notes, “Wittingly or unwittingly, the leader always shapes the norms of the group and must be aware of this function. The leader cannot not influence norms; virtually all of his or her early group behavior is influential” (p. 111; italics in original).

Furthermore, groups establish norms as a natural consequence of their operation and if the leader does not work to establish healthy norms in “an informed, deliberate manner” (Yalom, 1995, p. 112), the group itself may adopt norms that are maladaptive to the therapeutic process. Therefore, it is the responsibility of the therapist to provide a positive climate for therapeutic change. According to Billow (2005), conforming to adaptive group norms provides not only the clients, but also the therapist with a sense of identity, regularity, and security.

One example of the therapist’s influence on the group lies in the realm of self-disclosure and interaction. Billow (2005) indicates that in here-and-now interactions with the group a therapist’s words and actions betray much of his or her personality and values—disclosures made to the group that the therapist may only recognize in hindsight. Although group leaders often attempt to maintain a neutral, objective stance, they have “quite human presences whose subjectivity the group tests, monitors, and responds to with varying accuracy” (p. 175). The transparent milieu of group treatment beckons leaders to be mindful of principles associated with self-disclosure.

Therapist self-disclosure facilitates greater openness between group members; therefore, as the group progresses, therapists become more transparent and the therapeutic process is demystified (Yalom, 1995). Yalom advises that the content of effective self-disclosure includes such things as positive ambitions (e.g., personal/professional goals), personal emotions (e.g., loneliness, sadness, anger, worries, and anxieties), or accepting and admitting personal fallibility. Groups object to a leader expressing negative feelings about any particular member of the group or of the group experience as a whole (e.g., boredom, frustration). Therapists’ use of self-disclosure when they have similar personal problems (Yalom, 1995) or during the early phase of the group’s development may be harmful (i.e., the same disclosure with a more mature group could prove beneficial). Maslow (1962; as cited in Yalom, 1995) commented on this: “The good leader must keep his feelings to himself, let them burn out his own guts, and not seek the relief of catharting them to followers who cannot at that time be helped by an uncertain leader” (p. 213). Ultimately, the therapist considers the purpose of the self-disclosure and its value in assisting the group to achieve its therapeutic goals (Vinogradov & Yalom, 1989).

Emergent Structure

Group Development

Group dynamics typically refer to predictable changes that occur over the life of the group in the group structure (i.e., norms and member roles) and feeling tone (i.e., climate). Trotzer (2004) indicates that knowing the stages of group development “is a crucial dimension of a group leader’s competence” (p. 79). Although there are several models of group development, for illustrative purposes, MacKenzie (1994, 1997) is used due to its prominence in the empirical literature; this model describes four stages of group development —engagement, differentiation, interpersonal work, and termination.

Stage 1: Engagement

Stage 2: Differentiation Differentiation

is the process of self-assertion and self-definition in which members own, or become responsible for, their (and the group’s) progress in achieving treatment goals. Therapists can facilitate the differentiation process by reducing the level of structure they imposed in Stage 1 (Bednar, Melnick, & Kaul, 1974; Dies, 1993). An important by-product of the differentiation stage is member-to-member conflict; specifically, members’ ownership of their individual- and group-level treatment goals can lead to irritability and conflict as the group transitions from leader-established to member-owned (Brabender, 2002; Usandivaras, 1993). Members are also more comfortable in the group and begin to exhibit their “interpersonal habits and symptomologies” (Satterfield, 1994, p. 188). These conflicts provide group leaders with an opportunity to develop patterns for conflict resolution as well as model tolerance for negatively charged emotions (MacKenzie, 1997).

Stage 3: Interpersonal Work

The interpersonal work stage represents the shift to greater introspection and personal challenge as members address their individual problems more intensely. This stage of work can be devoted to higher levels of therapeutic work identified by the formal change theory guiding treatment. Success in this stage typically results in greater cohesion as members work together to solve common problems.

Stage 4: Termination

The termination stage represents the end of the group and comprises the last few sessions. Endings are typically difficult for clients of psychotherapeutic services so a structured approach can ensure that all members participate. A time-limited group creates an ideal environment for working through issues related to loss—“maturational tasks that are central to the human condition” (MacKenzie, 1997, p. 280).

Brabender (2002) offers therapists four reasons to track the group according to the developmental process. A developmental perspective helps the therapist:

Beyond these, by awareness of the group developmental stages, a therapist can enhance the qualitative value of the therapeutic factors. Factors associated with supportive features (e.g., universality) should be emphasized early in therapy during Stage 1. Factors associated with learning (e.g., vicarious learning) should be emphasized in Stage 2. Factors associated with self-revelation and psychological work (e.g., self-disclosure) should be emphasized later in therapy during Stages 3 and 4.

Feedback

Feedback is an important component in both leader-to-member and member-to-member interactions. Group feedback is defined as “any interaction between two or more group members in which reactions or responses to a particular activity or process are communicated” (Davies et al., 2006; p. 398). Kaul and Bednar (1994) note that “feedback from other members is commonly accepted as a critical therapeutic factor in group treatment and is so widely held that we would be embarrassed to mention it to an audience of group leaders” (p. 161). Morran, Stockton, and Teed (1998) summarized this empirical literature and concluded that feedback, over and above that which naturally occurs in groups, is related to more successful group and individual outcomes—heightened motivation for change, greater insight into how a person’s behavior affects others, increased comfort in taking interpersonal risks, and higher ratings of satisfaction with the group experience.

Interpersonal feedback may be related to better patient outcomes in group treatment because it increases cohesion. Members who report high levels of cohesion make more self-disclosing statements of important and meaningful material. These disclosures, in turn, lead to more frequent and intense interpersonal feedback among group members. Closeness and cohesion increase the likelihood that members will accept the feedback they receive from other members (Greller & Herold, 1975) and ultimately create better patient outcome (Burlingame et al., 2002). In Table 11.5; Davies et al. (2006) offer five recommendations to group therapists regarding how to encourage feedback between group members that will be productive in promoting higher levels of cohesion.

Table 11.5 Facilitating Feedback within the Group Session

1. Emphasize positive feedback during early stages of the group’s development, whereas in later stages balance between positive and corrective feedback. 2. Precede corrective feedback with positive feedback messages, or sandwich it between positive feedback messages to increase the likelihood that it will be received. 3. Focus feedback on specific and observable behaviors rather than vague complaints (i.e., “I feel uncomfortable when I ask you a question and you do not respond” versus “You seem aloof “). 4. Assess a group member’s receptiveness before delivering corrective feedback messages to them on an individual level (as opposed to corrective feedback to the entire group). < div class='tao-gold-member'>

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|