Figure 9.1 The reticular activating system

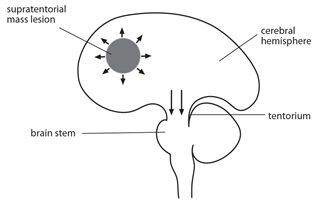

Figure 9.2 Sites that produce loss of consciousness

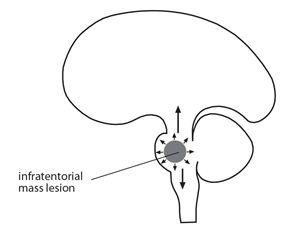

Figure 9.3 Sites that produce loss of consciousness

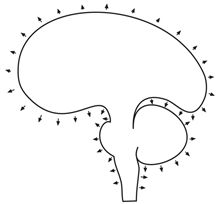

Figure 9.4 Encephalopathy diffuse

Table 9.1 Main disorders causing coma

| Site/aetiology | Disorder |

| Intracranial | |

| Focal stroke infections trauma tumours Diffuse infections seizures trauma | infarct, ICH, SAH brain abscess haematoma (ICH, EDH, SDH) primary or secondary HIV, meningitis, malaria, encephalitis post ictal/status epilepticus traumatic brain injury |

| Extracranial | |

| hypoxia metabolic/toxic hypertension | cardiac, respiratory, renal, shock, anaemia hyper-hypoglycaemia, organ failure, hyponatraemia overdose, opiates, alcohol encephalopathy, eclampsia |

Pathophysiology

Consciousness is a person’s awareness of themselves and their surroundings. Normal consciousness is maintained by an intact reticular activating system in the brain stem and its central connections to the thalamus and cerebral hemispheres. The reticular activating system keeps us awake and alert during the waking hours. Disorders that physically affect these areas can lead to disordered arousal, awareness and to altered states of consciousness. A focal brain lesion occurring below the tentorium (Figs.9.1 & 2) interfering with the reticular activating system can result in coma whereas a focal lesion occurring above the tentorium in one cerebral hemisphere results in coma only if the contralateral side of the brain is simultaneously involved or compressed (Fig.9.3) Diffuse lesions which affect the function of the brain as a whole including the reticular activating system can result in coma (Fig.9.4).

ASSESSMENT

Acute

Coma is an acute life threatening condition and evaluation needs to be quick, comprehensive and may involve starting emergency management even before the cause is established. Emergency management starts with an immediate assessment of airway, breathing and circulation (ABC) and involves the following steps. Firstly check that the airway is clear without secretions and that no cyanosis is present. This is achieved by rapid visual inspection and checking the vital signs. Secondly ensure that breathing rate is satisfactory (rate >10-12/min), that there are adequate breath sounds bilaterally on auscultation and that the oxygen saturation is >95%. If ventilation is inadequate or GCS is ≤8 then consider intubation and assisted ventilation. Thirdly check that the circulation is adequate by measuring pulse and BP. If the systolic blood pressure is <90 mm Hg then start immediate fluid resuscitation, and with inotropic support if BP remains persistently low despite adequate volume replacement. Fourthly insert an IV cannula and withdraw blood for laboratory studies. All comatose patients should have their blood glucose checked on arrival and treated immediately if hypoglycaemic (blood sugar <2.5 mmols/l) or hyperglycaemic. Finally treat any other immediately reversible cause without delay e.g. iv thiamine 100 mg in patients with history of alcoholism and naloxone 0.4-2 mg in patients with drug habituation (Table 9.4). If the patient is stable, then the clinical assessment can start.

Key points

- airway: make sure it is clear

- breathing: count RR & listen to the lungs, if respiration inadequate give O2 & ventilate

- circulation: check pulse/BP and treat if systolic <90 mm Hg

- glucose: check urgently and treat any reversible cause immediately

Clinical assessment

This involves history, general examination, level of consciousness and neurological examination.

The history

The history is the most important part of the assessment as it frequently points to the underlying cause of coma. The diagnosis may already be obvious from the circumstances surrounding the coma e.g. head injury in a road traffic accident (RTA), stroke in hypertension or hyperglycaemia or hypoglycaemia in diabetes or a seizure in epilepsy. If the cause is not obvious then it is necessary to obtain a history from the patient’s family members, friends or colleagues. The history should include information and details concerning the immediate circumstances and the possible cause of the coma. It should also include the patient’s previous medical history, medications, allergies, possible toxins and details of social and family history including recent travel or anything relevant. In particular, ask if there was a recent preceding illness e.g. fever, headache, if the onset was sudden or gradual and check specifically for a history of trauma or fall, a history of epilepsy, alcohol or drugs. The main causes of coma are outlined below (Table 9.1).

Key points

- loss of consciousness is a medical emergency

- assessment needs to be brief and focused

- history is the most important part of the initial assessment

- cause may be obvious & reversible causes need to be considered

- main causes are head injuries, encephalopathies, infections & strokes

Easy way to remember the causes of coma

A = anoxia/apoplexy

E = epilepsy

I = injury/infection

O = opiates

U = uraemia

The general examination

This involves confirming the vital signs and checking for evidence of obvious injury or major underlying illness. Signs of head injury/basal skull fracture include lacerations or bruising to the head, around the eyes, behind the ear (Battle’s sign) or CSF leak from the nose or ears (Chapter 19). Palpation of the head/neck may show signs of a fracture and swelling. Signs pointing to an underlying illness include paresis, hypertension, tongue biting, ketoacidosis, jaundice and evidence of infection including fever, meningitis, and pneumonia or discharging ear.

The level of consciousness (LOC)

This is the most important part of the assessment of the unconscious patient. Altered states of consciousness range from confusion and delirium to stupor and coma (appendix 1). Confusion is characterized by the patient being fully conscious but with impaired attention, concentration and orientation. Confusion can be tested at the bedside by checking if the patient is fully orientated in time, person and place with a score of 10/10 being fully orientated (Table 9.2).

Table 9.2 Testing for orientation 10/10*

| Time | Person | Place |

| time day month year | name age year of birth | hospital town/district country |

*score one for each correct answer

In a state of delirium, the patient although fully conscious is confused and restless with hallucinations. In a state of stupor, the patient is in coma but is rousable after intense stimulation; this is in contrast to coma where the patient is unrousable. In general the use of these terms has been replaced by the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) (Table 9.3).

Table 9.3 Glasgow Coma Scale

| Best response | Score | |

| Eye opening (E) | spontaneously to speech to pain nil | 4 3 2 1 |

| Motor response (M) | obeys commands localizes stimulus flexes withdrawal flexes weak extension nil | 6 5 4 3 2 1 |

| Best verbal (V) | oriented fully confused inappropriate incomprehensible (sounds only) nil | 5 4 3 2 1 |

| Maximum score | 15 |

Glasgow coma scale

The depth of coma can be measured by the GCS. This measures eye opening, best motor and verbal response, and is a reliable method for measuring and monitoring level of consciousness. It should be carried out and if necessary repeated on every comatose patient. When using the GCS, look carefully at the patient’s face while assessing eye opening, and then check on the patient’s ability to follow simple motor commands and listen to the patient’s speech for content and orientation. If the patient is not responding to voice then test eye opening and limb movement response to deep pain by applying pressure to sternum or supra orbital ridge or nail beds. Record best eye opening, motor and verbal response as E4, M6 and V5. Patients are considered comatose if the GCS ≤ 8/15.

The AVPU Method

A more simplified bedside assessment of the level of consciousness is the AVPU method (yes/ no response). Its advantages are that it assesses the main levels of consciousness quickly and is easy and quick to use and communicate.

AVPU method

A: is the patient alert

V: is the patient responsive to voice

P: is the patient responsive to pain

U: is the patient unresponsive

Key points

- check the vital signs

- examine for signs of head injury or a systemic disorder

- assess the level of consciousness

- level of consciousness is the most important part of the assessment

THE NEUROLOGICAL ASSESSMENT

This frequently gives the clues towards establishing the aetiology of the coma. The neurological assessment in coma is necessarily shortened concentrating on the possible neurological causes of coma e.g. stroke, meningitis and the presence of any localizing signs. Note the level of consciousness and any obvious neurological abnormalities such as seizures, the pattern of breathing and the position of the eyes and posture of the trunk and limbs. In particular, record pupil size, equality, response to light and eye position or movements. Normal pupils are 3-4 mm in diameter and respond briskly to light. Abnormalities include fixed dilated pupil (s), >7 mm in size and non reactive to light. In states of coma the most common cause of a unilateral fixed pupil is herniation (Table 9.4.) and of bilateral fixed pupils is brain death. The presence or absence of the corneal reflexes should be noted and fundi checked for papilloedema. If there is no contra indication to moving the neck such as spinal or head injury neck stiffness should be tested although its absence is unreliable in coma.

Table 9.4 Main localizing neurological features & causes in coma

| Neurology finding | Localization | Main causes |

| Respiration pattern Cheyne Stokes (breathing progressively deeper and then shallower in cycles) | brain stem herniation/encephalopathy | ↑ICP, stroke |

| Eye position eyes looking to one side (conjugate deviation) | unilateral lesion | stroke, head injury & any focal lesion |

| Pupils fixed & dilated pupils a fixed & dilated pupil pin point pupils | brain herniation of medial temporal lobe through tentorium compressing 3rd CN pontine lesion | anoxia, trauma, brain death unilateral mass lesion above tentorium due to any cause stroke, organophosphorous poisoning, opiate overdose |

| Meningism | meningeal inflammation | infections & haemorrhage |

| Limb position hemiparetic/asymmetrical arms flexed, legs extended all 4 limbs hyper extended & extensor posturing to pain | unilateral lesion decorticate posturing decerebrate posturing | stroke & any focal lesion cortical damage brain, brain stem damage |

| Limb examination hypertonia & hyperreflexia & extensor plantars bilateral extensor plantars | brain/cord non localizing | any diffuse or focal lesion coma any cause |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree