extramedullary

AETIOLOGY

Paraplegia can arise from a lesion either within or outside the spinal cord or cauda equina. These are classified as compressive and non compressive. Compression is caused either by bone or other masses. The main compressive causes are Pott’s disease (TB of spine) and tumours (usually metastases). The main non compressive causes are transverse myelitis secondary to viral infections, HIV, TB and very occasionally syphilis. Less common causes include Devic’s disease, B-12 deficiency and helminthic infections. There also exists in Africa a large group of nutrition related non compressive paraplegias, termed the tropical myeloneuropathies. These include konzo, lathyrism and tropical ataxic neuropathy (TAN). The main causes of paraplegia are presented in Table 10.1.

Common causes of paraplegia in Africa

- Pott’s disease (TB)

- inflammation (transverse myelitis)

- malignancy (metastases)

- infection (HIV)

- nutritional (konzo)

Localization/anatomy

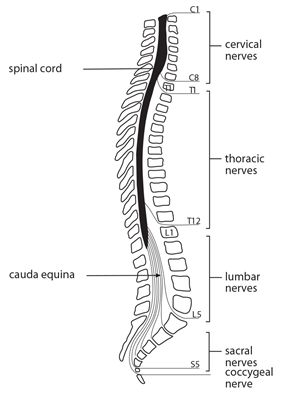

The spinal cord extends from C1 in the neck to the lower border of L1 (Fig. 10.1). The cauda equina extends from the end of the cord down to S5 within the sacral canal. Paraplegia arises from disorders affecting the thoracic spinal cord and the cauda equina, whereas quadriplegia or quadriparesis arises from disorders affecting the cervical cord. The most important information to elicit at the bedside is whether paraplegia is spastic or flaccid in type and whether there is a sensory level on the trunk above which sensation is normal (Chapter 2). This helps to localise the site of the lesion causing the paraplegia.

Figure 10.1 Spinal cord. Spinal nerves and vertebral column.

Key points

- paraplegia is a common neurological disorder

- clinically classified as compressive & non compressive

- main causes are Pott’s disease, transverse myelitis & malignancy

- the most common community based cause is nutritional myelopathy

- disorders of the spinal cord result in a spastic PP

- disorders of the cauda equina result in a flaccid PP

COMPRESSIVE CAUSES

The causes of compressive paraplegia can be classified on neuroimaging (CT/MRI) as being either extradural or subdural in site. Subdural includes those arising from either within the spinal cord (intramedullary) or those arising outside the cord (extramedullary) (Table 10.1). The two main compressive causes in Africa are Pott’s disease and metastatic malignancy, both of which are extradural. Acute cord compression is a medical emergency and needs rapid evaluation and intervention in order to prevent permanent disability. The history and neurological examination localise the level of weakness, and help to determine the likely cause of the paraplegia. However on their own without further laboratory and imaging investigations they may not reliably distinguish the cause.

Spinal TB

Spinal TB accounts for <10% of extrapulmonary TB. Extrapulmonary TB accounts for about 15% of all TB. Spinal TB can result in paraplegia in two main ways, either by infection of the spine (Pott’s disease) accounting for the majority of cases of paraplegia or less commonly by direct infection of the spinal cord and cauda equina (spinal cord tuberculosis).

POTT’S DISEASE

Pott’s disease is a leading cause of paraplegia in Africa and is the most common cause in childhood, adolescence and in young adults. It arises from haematogenous spread of the tubercle bacillus from pulmonary infection. The paraplegia occurs either at the time of the primary infection or more commonly 3-5 years later by reactivation. This results in infection of the spine affecting the intervertebral disc space and adjacent vertebrae which if not treated may result in characteristic extradural compression of the spinal cord causing paraplegia.

Clinical features

The main clinical features of Pott’s disease are a history of localised back pain, over weeks or months, which is made worse by weight bearing and followed by a slowly progressive paraplegia. The paraplegia may be accompanied by low grade features of active systemic TB including fever, sweating and weight loss but this is not common. Neurological examination confirms paraplegia, the clinical signs depending on the level and the extent of the lesion. The lower thoracic and the lumbar spine are the most common sites affected. The spine should be carefully inspected for signs of local tenderness and the presence of any deformity, in particular a gibbus formation. A gibbus is a visible angular deformity of the thoracic or lumbar spine caused by collapse and anterior wedging of adjacent vertebrae. Local tenderness is best elicited by gently tapping the spines of the vertebrae with a finger tip or a patellar hammer.

Investigations

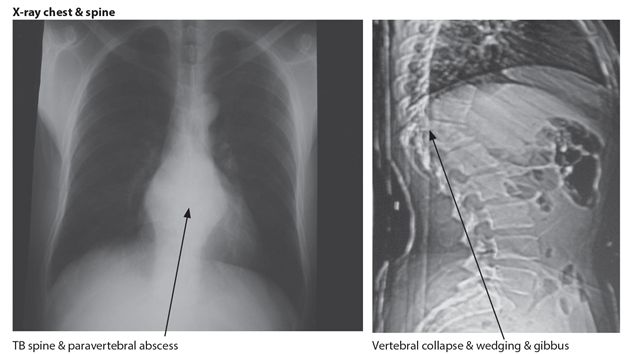

The ESR is typically elevated early on and throughout the course of Pott’s disease and may be the only laboratory clue as to the likely underlying cause. Radiological evidence shows a characteristic loss of the disc space at the site of infection with destruction and wedging of adjacent vertebrae but the latter is a late finding. There may also be a paravertebral soft tissue swelling (Fig. 10.2) or uncommonly a psoas muscle abscess. A CT scan of the spine may also be helpful, particularly in early disease when plain X-rays may be normal. The diagnosis of Pott’s disease is usually made by clinical suspicion, in combination with an elevated ESR and typical spinal X-rays. All suspected cases of Pott’s disease should have a chest X-ray to exclude active pulmonary tuberculosis.

Figure 10.2 Pott’s disease

Treatment

Treatment is mostly carried out on clinical and X-ray grounds alone. Where possible a needle biopsy confirming the presence of acid fast bacilli should be performed and this is diagnostic. The standard anti tuberculous treatment for spinal TB is for a total of 18 months, however a shorter 12 month course has been recently recommended. Surgical treatment involving decompression of the cord and stabilization of the spine is helpful in a few mainly early cases of spinal cord compression.

Prognosis

The treated mortality rate is between 10-20% and full recovery rates of from 25 to 40%.

SPINAL CORD TUBERCULOSIS

Direct infection of the spinal cord with TB presents clinically either as an acute myelitis developing over days or as a chronic radiculo-myelitis (Fig. 10.3) occurring over weeks to months. The resulting paraplegia is mostly lower motor neurone or flaccid in type with absent or depressed reflexes with urinary and faecal incontinence. Tuberculoma of the cord may also result in paraplegia but this is uncommon. TB meningitis may also arise from a source of infection within the spinal cord and the combination of TB meningitis and paraplegia is not uncommon in Africa. All patients presenting with paraplegia should be screened for HIV infection. The diagnosis and management of spinal cord tuberculosis is similar to that of TBM which is presented in Chapter 6.

Figure 10.3 TB cauda equina

Key points

- Pott’s disease is one of the most common causes of PP in Africa

- PP can also arise from direct TB infection of spinal cord or meninges

- clinical features of Pott’s disease are back pain, spinal tenderness & progressive PP

- laboratory findings are a high ESR with typical spinal x-ray changes

- treatment is with anti TB Rx for at least 12 months

- CFR is 10-20% & morbidity rate is 25-40%

TUMOURS

Tumours affecting the spinal cord can be either primary arising from the cord, roots or meninges or secondary or metastatic arising from outside the cord. The most common overall cause of spinal cord tumours is secondary or metastatic. The main sources are prostate, breast, lung, kidney, lymphoma and multiple myeloma. They are mostly located extradurally and the most common sites affected are the thoracic followed by the lumbar spine. These are the main cause of paraplegia in older age groups (>50 years). Primary spinal cord tumours are very uncommon with an expected incidence of <1/100,000 per year and can occur in all age groups. These include meningioma arising from the meninges, neurofibroma arising from peripheral nerves and astrocytoma and ependymoma arising from the cord.

Clinical features

Patients presenting with paraplegia resulting from metastatic tumours typically have a history of localised back pain in combination with a mainly flaccid type paraplegia developing over a short period, usually days or weeks. Pain arising from the spinal site of metastasis is usually a distinctive feature. The paraplegia may be the first presenting complaint or a complication of known systemic malignancy. In contrast benign tumours tend to present with paraplegia evolving more slowly over months or years, and pain is less pronounced.

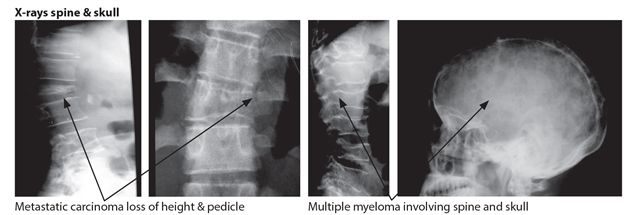

Investigation

Investigations help to confirm the suspicion of a malignancy with plain spinal x-rays showing lytic or blastic lesions or vertebral collapse depending on the primary (Fig. 10.4). CSF may sometimes show a high protein level and yellow discolouration particularly if there is a block to flow resulting in a concentration of CSF constituents. This is called the Froin syndrome. Neuroimaging (CT/MRI) of the spinal cord is necessary in all patients with suspected primary cord tumours and in some with suspected metastatic tumour.

Figure 10.4 Malignancies

Treatment

The treatment depends on the type of underlying tumour. Metastatic tumours causing cord compression initially require urgent steroids and analgesia if needed. More definitive treatments include local radiotherapy and occasionally surgical decompression. Chemotherapy may be helpful in patients with lymphoma and myeloma, whereas hormonal therapy can be very beneficial in those with metastatic breast and prostate cancer. Some benign tumours can be removed depending on their histology, size and local invasiveness. The prognosis for metastatic spinal cord tumour is generally poor.

Key points

- metastatic malignancy is the most common cause of PP in the elderly

- prostate and breast are the most common primary sources

- paralysis is usually painful & flaccid with a sensory level on the trunk

- treatment includes steroids, analgesia, radiotherapy & chemotherapy

ACUTE EPIDURAL ABSCESS

Acute spinal epidural abscess is a relatively uncommon cause of paraplegia but is a medical emergency when it happens. It tends to occur in debilitated patients with diabetes, alcoholism or renal failure but may occur in an otherwise healthy person. Staphylococcus aureus is the most common organism accounting for 90% of cases, skin abscesses and boils are the most common sources of infection. It can affect all age groups.

Clinical features

The clinical features are those of a painful sub acute paraplegia developing over hours or days. The distinguishing features are very severe pain, sometimes radicular, and local tenderness at the site of the epidural abscess which is usually situated in the cervical or lumbar spine. These are frequently but not always coupled with fever and signs of infection with or without meningism.

Investigations

Investigations suggest a bacterial cause when the peripheral WBC (neutrophil count) and ESR are both elevated but these can be normal. CSF examination may reveal the presence of a few white blood cells and elevated protein level or be normal. Lumbar puncture should not be performed near the suspected abscess site as this may spread the infection to the CSF causing meningitis. A CT scan of the spinal cord with contrast may show epidural enhancement but can also be normal. MRI of the spinal cord with contrast is the investigation of choice.

Treatment

Emergency treatment is recommended on the grounds of clinical suspicion without waiting for the results of any investigations. Appropriate high dose intravenous antibiotics including cloxacillin are started and continued for a period of up to 6 weeks. High dose intravenous steroids may be of value if given early on during the first week or two of treatment. Urgent decompressive laminectomy may sometimes be indicated.

Key points

- epidural abscess is a medical emergency which requires urgent treatment

- sub acute painful PP occurring over hours or days

- occurs in DM, alcoholism, renal failure & skin infection & in healthy persons

- diagnosis is confirmed by contrast enhanced CT/MRI spinal cord

- treatment is iv antibiotics & steroids & sometimes surgery

CERVICAL SPONDYLOSIS

This is one of the most common causes of paraplegia in high income countries but appears to be a relatively uncommon cause in Africa.

Clinical features

Affected patients are usually older, >60 yrs and typically present with a slow insidious onset of weakness or stiffness in the legs, sometimes coupled with numbness and tingling in the upper limbs. There may be a history of previous neck injury or accident. Pain and bladder symptoms are uncommon. The main clinical findings are those of a spastic paraplegia coupled with wasting of the small hand muscles.

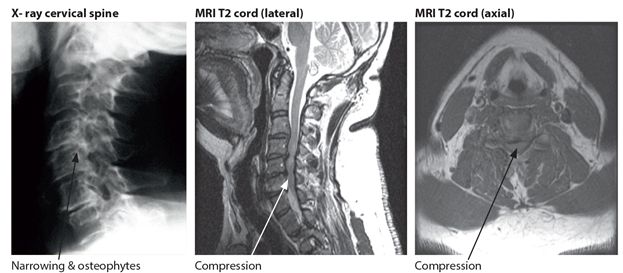

Investigations

Plain X-ray or CT of the cervical spine confirms the diagnosis, showing narrowing of one or two disc spaces with prominent osteophytes, narrowing of the cervical canal and evidence of cord compression (Fig. 10.5).

Figure 10.5 Cervical spondylosis

Management

Management is mostly conservative and includes analgesics, cervical collar and very rarely traction. Indications for consideration for decompressive surgery include progressive paraplegia, severe weakness and intractable pain. Surgery is aimed at the prevention of any further deterioration rather than making the patient better, although neurologic improvement is occasionally seen.

Key points

- cervical spondylosis is an uncommon cause of PP in Africa

- presents with slow onset spastic PP with numbness & wasting in hands

- occurs in older persons, often with a history of previous neck injury

- X-ray/CT neck: narrow disc spaces & canal with osteophytes & cord compression

- treatment usually conservative with analgesics & cervical collar

FLUOROSIS

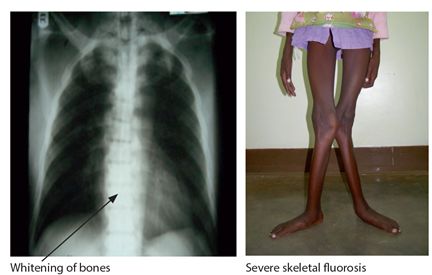

Fluorosis is a disorder characterized by the deposition of excess fluoride in bones (osteofluorosis) and teeth (dental fluorosis). It results from chronic ingestion of fluoride rich waters over many years. Water contamination with fluoride occurs naturally in volcanic areas of the world. This is particularly the case in volcanic areas in the rift valley region of East Africa where there can be exposure to high levels of fluoride in drinking water. The degree of water contamination and exposure can vary enormously within adjacent areas in affected regions. Neurological disorders are uncommon and arise in fluorosis as consequence of the chronic deposition of fluoride in bone occurring over many years. This can result in narrowing of the diameter of the spinal canal and the intervertebral foramina which can cause compression. It mainly affects the cervical canal but may also affect the lumbar sacral canal. The resulting neurological disorders are mostly forms of spastic paralysis with or without associated radiculopathies. These lead to quadriplegia and paraplegia characterized by immobility, flexion deformities, severe spasms, and urinary incontinence. The diagnosis is usually suggested by the typical clinical and X-ray findings occurring in a person from a known volcanic area (Fig.10.6). Treatment is symptomatic. Primary prevention is the intervention of choice either by filtering all water at the point of access or drinking water at the point of usage.

Figure 10.6 Fluorosis

Key points

- skeletal fluorosis results from chronic high fluoride intake in drinking water

- cervical & lumbosacral spine are most commonly affected sites

- result in a quadri/paraparesis & radiculopathy

- PP is an uncommon complication of skeletal fluorosis

- skeletal X-rays confirm the diagnosis

- prevention is by filtering drinking water

SYRINGOMYELIA

This is an uncommon disorder in which a CSF filled cavity called a syrinx forms in the centre of the spinal cord. The time course of symptoms and signs is one of slow progression over many years. It typically starts slowly in the lower cervical cord and over many years, the cavity can involve the whole spinal cord down to T12 & L1. The cause is considered to be related to abnormalities in the dynamics of local CSF pressure and flow. Predisposing causes include a developmental abnormality of the skull base with flattening or platybasia coupled with variable protrusion of the lower brain stem and cerebellar tonsils through the foramen magnum. This is called the Arnold-Chiari malformation. Neck and cervical cord injury is another risk factor which is an important cause in Africa, particularly in women because of falls whilst carrying heavy loads on the head. There is usually a gap of 20-30 years from the time of the accident to the onset of first symptoms.

Clinical features

Syringomyelia results in a characteristic pattern of motor and sensory deficits with signs of a spastic paraplegia in the legs, and lower motor neurone signs in the upper limbs. Pain is a feature; this is often severe, burning or neuropathic in type and often in a radicular distribution in the limbs. The sensory findings are diagnostic, with involvement of the spinothalamic tracts producing loss of pain and temperature in a characteristic cape distribution over the shoulders. Sensory involvement occurs in the arms and legs depending on the site and extent of the syrinx. Because the cavity is situated in the centre of the cord there is sparing of the posterior columns with preservation of joint position, vibration and light touch. Characteristic clinical findings include neuropathic scars because of the loss of pain sensation, wasting of small hand muscles and claw hand deformities (Fig. 10.7). The clinical course in severe cases is a slowly progressive quadriplegia or paraplegia occurring over many years with the patient gradually becoming wheelchair and bedbound.

Figure 10.7 Hands in syringomyelia

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree