16 Coma, Vegetative State, Brain Death, and Increased Intracranial Pressure

Coma

Clinical Vignette

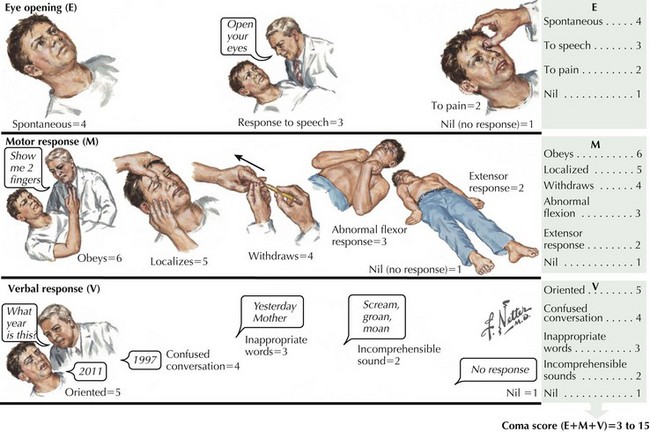

The Glasgow Coma Scale assesses and quantifies the degree of consciousness across three measures: response to verbal commands, response of eye opening, and the nature of motor movements in response to verbal or physical stimuli. Those not responding to verbal commands or opening their eyes with a Glasgow Coma Scale score of 8 or less are defined as being in a coma (Fig. 16-1). The Glasgow Coma Scale is one of the primary predictors of long-term outcomes, especially in cases of head trauma.

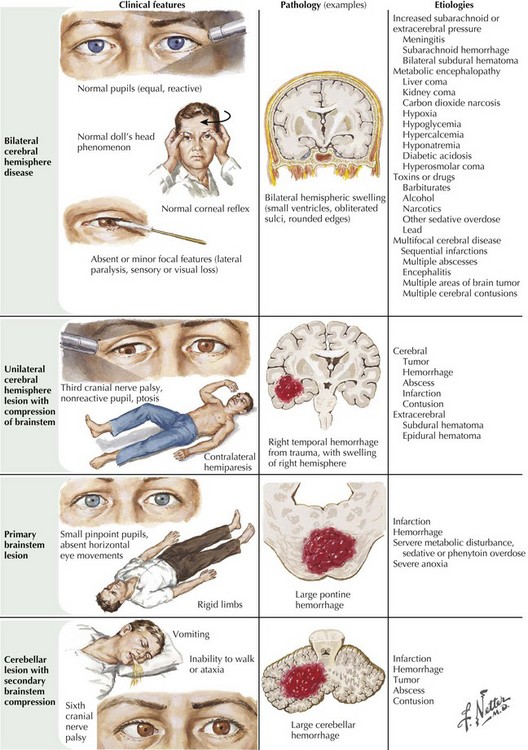

Prevalence of the different etiologies of coma varies depending on the population surveyed. For example, head trauma and intoxicants are the major causes in registries based on densely populated high-crime areas. Stroke and cardiac events are the leading etiologies in suburban areas with retirement communities. Overall, trauma, stroke, diffuse anoxic–ischemic brain insult (secondary to cardiorespiratory arrest), and intoxicants are the leading mechanisms for coma. Infections, seizures, and metabolic–endocrine disorders account for the remaining cases (Fig. 16-2).

States that affect cognition and attention without affecting wakefulness such as the various degenerative dementias (characterized by progressive cognitive deterioration) and focal brain lesions (which cause restricted cortical dysfunction) do not fit the definition of coma. Sleep is a normal patterned physiologic disconnection of the cortex from external stimuli and is discussed elsewhere (Chapter 15).

Evaluation and Treatment of the Comatose Patient

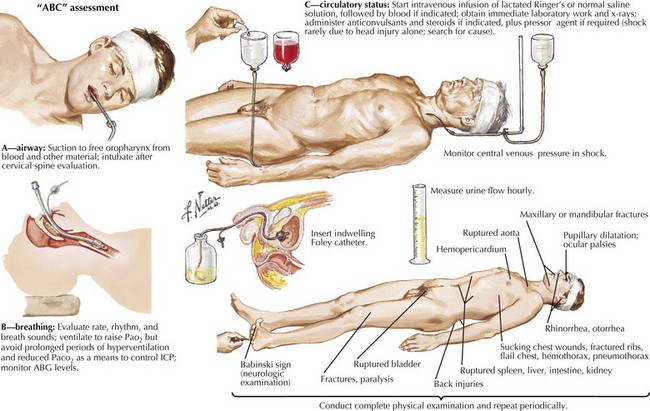

The initial evaluation of a patient in coma must occur simultaneously with its management. Any delay in treatment while waiting to determine the exact cause is not acceptable. Clearing the airway and ensuring adequate ventilation and oxygenation with a bag mask or intubation, if needed, must be addressed immediately. Management of hypotension must be prompt, especially in suspected cases of increased intracranial pressure (ICP). Hemodynamic collapse should never be attributed to an intracranial process, and cardiac or circulatory causes need to be sought. These form the “ABCs of coma management”: airway, breathing, and circulation (Fig. 16-3). Immobilizing the neck until a cervical spine injury is excluded is also important in cases of suspected trauma.

Urgent intravenous antibiotic coverage is indicated for febrile patients because time is crucial in treating meningitis and septicemia (Chapter 48). Lumbar puncture should be performed only after brain imaging has excluded mass lesions that could lead to herniation.

Prognosis

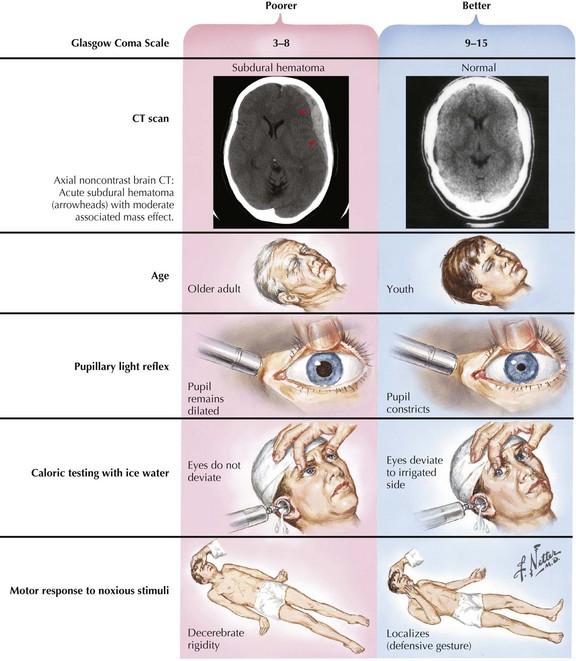

In most instances, coma from head trauma has a better outcome than that from nontraumatic mechanisms or cardiac arrest. Although severe head trauma has a mortality of approximately 50% within the first 48 hours, few surviving patients remain in a permanent vegetative state and most progress toward some degree of functional improvement. Those who remain vegetative usually succumb within 3–5 years. There are rare reports of patients who awaken after a prolonged vegetative period and show some return of functionality. None, however, return to their premorbid status or even an independent state. Signs that correlate with a poor prognosis after head trauma are age older than 60, bilateral pupillary abnormalities or absent oculocephalic reflexes at initial examination in a relatively stable patient. Large volumes of contused brain, large intra- or extra-axial hematomas, and lack of intracranial pressure response to conventional medical treatment (usually associated with compression of basal cisterns on CT) also betoken a poorer prognosis (Fig. 16-4).