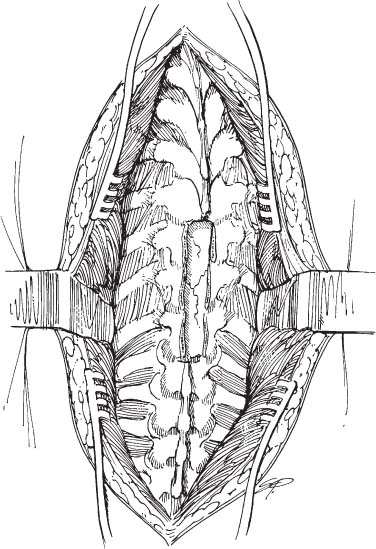

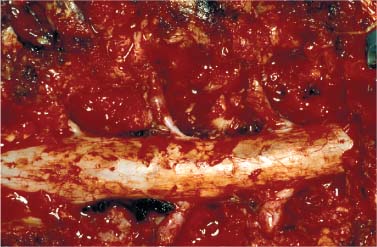

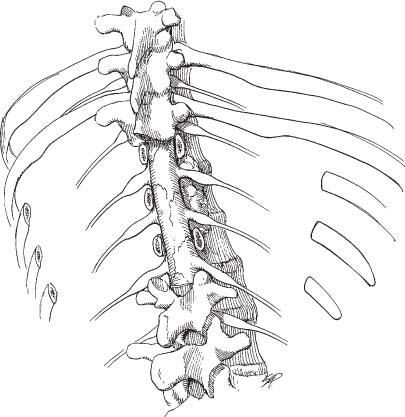

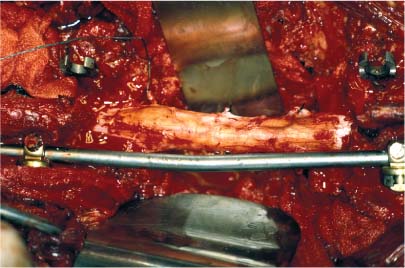

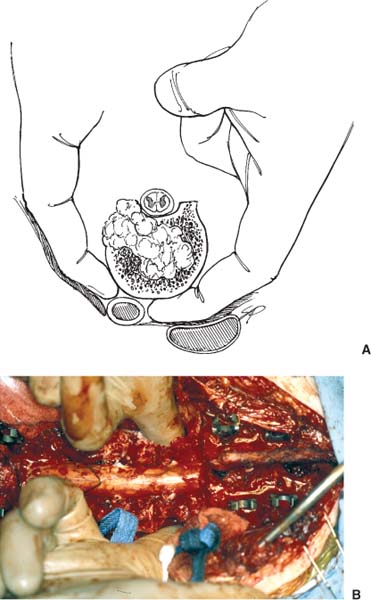

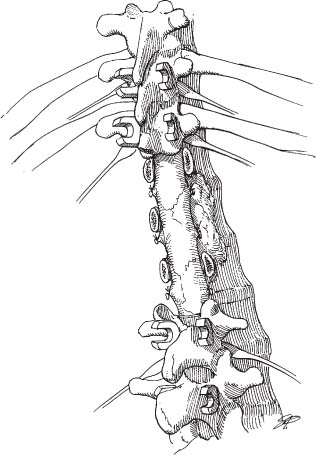

34 Even with the recent philosophical shift toward minimally invasive approaches to the spinal column, there will still be indications for more invasive spinal procedures, at least in the foreseeable future. Advances continue in adjunctive treatments for spinal disorders, including modalities such as radiation and chemotherapy, and even experimental treatments such as gene therapy and immunologic interventions. Nonetheless, definitive en bloc resection is still necessary for certain spinal neoplasms. Spondylectomy is a core approach that must be included in the armamentarium of surgeons dealing with spinal neoplasms. Spondylos comes from the Greek and means vertebra; spondylectomy is used to describe the procedure of removing the vertebra completely. The technique represents a surgical tour de force and is highly effective when performed well in the appropriate surgical candidates. Surgery for spinal neoplasms has constantly evolved beginning with the posterior approaches first described by LeCat,1 Macewen,2 Cushing,3,4 and Elsberg.5,6 Comfort with the posterior approach made it the defining tool of neurosurgeons during the first half of the 20th century. Advances by Hodgson and Stock,7 Lane and Moore,8 and Humphries and coworkers9 added anterior techniques to the armamentarium. In parallel, more aggressive posterior approaches were developed by pioneers such as Ito et al,10 Harmon,11 and Capener.12 Stener13 first described a complete spondylectomy and was followed by many others.14–31 Various techniques, ranging from a pure posterolateral approach to combined anterior and posterior approaches, have been used with various degrees of success. Deciding which approach is best for a certain case depends on the exact location and extent of the pathology, the surgeon’s familiarity with the approach, and the goal of intervention. The goal of spondylectomy is to remove a spinal tumor en bloc with a margin of normal bone tissue. Complete spondylectomy is best suited for well-demarcated primary spinal neoplasms that involve all vertebral elements circumferentially, that have not metastasized, and that have not invaded intradurally. This approach may also be used for solitary spinal metastases in the absence of widespread metastatic disease. An accurate and honest appraisal of disease burden and life expectancy is critical in choosing the most appropriate surgical approach for patients with malignant neoplasms of the spine. Most surgeons would consider intervening in the case of a patient with terminal cancer who was rapidly becoming paraparetic from spinal cord compression; however, a long life expectancy and the absence of widespread metastatic disease can help sway surgeons from a palliative approach to a more durable solution like complete spondylectomy, which is potentially curative. Multifocal metastases and a limited life expectancy are contraindications to spondylectomy. The optimal timing of surgery for spinal neoplasms, especially malignant lesions, is also controversial. Acute decompression of a patient with spinal cord compression is well accepted. However, the role of surgery in an asymptomatic patient is controversial. Sundaresan et al32 described the only prospective study that evaluated the role of surgical decompression in patients with neoplastic spinal cord compression. They found that patients undergoing de novo surgery had better outcomes than those treated with external radiation therapy and steroids alone. The watershed zone of the spinal cord supplied by the anterior spinal artery in the thoracolumbar region poses a potential risk of vascular injury for thoracolumbar junction tumors treated with complete spondylectomy.33–35 There have been reports of anterior spinal artery syndrome following spinal surgery, and it may be unavoidable in some cases. The surgeon may consider preoperative angiography to determine the level and morphology of the artery of Adamkiewicz in patients with tumors in the T9 through L1 regions of the spine who are under consideration for complete spondylectomy. If appropriate, preoperative embolization of the tumor could also be undertaken to reduce the blood supply to the tumor. Angiography is especially helpful with vascular tumors (i.e., renal cell carcinoma, thyroid carcinoma, etc.). Complete spondylectomy is a formidable surgical procedure, often requiring combined anterior and posterior approaches or a large posterolateral approach. Complete spondylectomy in the thoracic spine is best suited for patients with disease processes associated with a high likelihood of long-term control. The best example would be a primary tumor of the spine that ostensibly could be cured with radical resection. Complete spondylectomy has been performed in the cervical, thoracic, lumbar, and sacral regions of the spine. This chapter focuses on the techniques associated with thoracic and lumbar spondylectomy. Techniques for sacrectomy are discussed elsewhere in this book. Choosing a suitable surgical approach for patients with spinal neoplasms also requires considering the location and extent of the disease. Tumors confined to the vertebral body are best accessed with anterior approaches. Tumors that involve laminae, facets, and spinous processes are best accessed posteriorly. Tumors that involve all three columns of the spine can be accessed through wide bilateral costotransversectomies or through combined anterior and posterior approaches. During surgical planning, the preoperative imaging studies must be reviewed carefully to ascertain whether the tumor extends beyond the ventral plane of the vertebral body and whether it encases, invades, or displaces the aorta or vena cava. An accurate radiographic impression of potential pitfalls is critical. An anterior extension of a tumor that encases or invades one or both of the great vessels or the mediastinal structures cannot be cured with spondylectomy. Also, intradural tumor invasion precludes a surgical cure with a spondylectomy. Such lesions would most likely be addressed best through a palliative surgical approach or nonsurgical treatments rather than through a complete spondylectomy. Lesions that involve the vertebral bodies and the posterior elements are candidates for spondylectomy. Complete spondylectomy is best suited for patients in whom the neoplastic process involves all three columns of the spine, or at least the anterior or middle column and the posterior column. Preoperatively, it is important to distinguish patients who would potentially benefit from the wide resection offered by a spondylectomy from those who are best treated by palliative surgery or nonsurgical treatment. Tomita et al,36 therefore, devised a strategy to determine which patients are best suited for radical surgery. Their scoring system is based on three prognostic factors: grade of malignancy (slow growth, 1 point; moderate growth, 2 points; rapid growth, 4 points); visceral metastases (no metastasis, 0 points; treatable, 2 points; untreatable, 4 points); and bone metastasis (solitary or isolated, 1 point; multiple, 2 points). When summed, the total possible score ranges from 2 to 10. This prognostic score was used to determine which patients were offered radical surgery. A score of 2 or 3 suggests that a wide or marginal excision is indicated for long-term control. A score of 4 or 5 indicates that marginal or intralesional excision is indicated for intermediate-term control. A score of 6 or 7 justifies palliative surgery for short-term control, and a score of 8 to 10 indicates the need for nonoperative supportive care. Although therapies always must be tailored to the individual patients, this framework can be used to review a patient’s suitability for surgery. Preparations for this procedure require a thorough medical evaluation, including chemistries, a complete blood count, electrocardiography, chest radiography, systemic evaluation to assess for metastatic disease, and pulmonary function testing if indicated. Packed red blood cells should be available as well. Intraoperative fluoroscopy is a critical component to confirm the surgical level and to help insert spinal instrumentation. Spine and chest radiographs and imaging studies must be reviewed to confirm the correct location of the pathology and to demonstrate the extent of the disease. Intraoperatively, we also monitor somatosensory-evoked potentials as an indicator of neurologic compromise. Frameless stereotaxy and intraoperative CT scans can be valuable adjuncts, helping to place thoracic pedicle screws accurately and to verify the margins of tumor within a vertebral body. Given all of the approaches used for complete spondylectomy, it is paramount that all bone and tumor are resected sharply with bone rongeurs, osteotomes, and Gigli saws. Pneumatic drills should be avoided because their use creates tumor debris that could seed the surgical bed. For the purpose of this discussion, the technique for complete lower thoracic (T10 through T12) spondylectomies with reconstruction and stabilization is described. The patient is placed in the prone position on an operating table. Chest rolls, a Wilson frame, or a Jackson spinal table is used. A long midline posterior incision from T6 through L2 is necessary to obtain satisfactory lateral exposure and for spinal fixation. Laminectomies are performed at the levels to be excised (T10–T12) (Fig. 34-1). The facets, transverse processes, and pedicles are then removed at the levels of interest (Fig. 34-2). All bone is resected sharply with bone rongeurs. Drills are avoided to prevent creating tumor debris that could seed the operative site. The ribs at the levels for the spondylectomy are resected widely; the proximal 10 to 12 cm are removed bilaterally (Fig. 34-3). The thoracic nerve roots are ligated with sutures and sectioned near their origin at the dural tube to provide unobstructed access for dissection and tumor removal. A subpleural exposure is performed using a sponge stick to elevate the pleura from the lateral and ventral surfaces of the spine. Malleable retractors are inserted to maintain exposure of the vertebral bodies and segmental vessels. The intercostals arteries are ligated, coagulated, and sectioned (Fig. 34-4). The anterior surfaces of the vertebral bodies are dissected bilaterally. Wide, blunt, malleable, hand-held laparotomy retractors can be used to depress the pleura and to aid visualization of the anterior and lateral aspects of the vertebral body. The segmental arteries and veins on the surfaces of the vertebral bodies are identified, mobilized, and ligated with hemoclips or suture ligatures. Subperiosteal dissection with sponge sticks or peanut dissectors is used to separate the azygos vein, aorta, esophagus, and thoracic duct from the surface of the vertebrae. The most anterior portion of the dissection is performed bluntly with a finger (Fig. 34-5). Gentle blunt finger dissection is required to complete the tissue mobilization and avoid tearing the azygos vein. Laparotomy sponges are inserted to protect the mediastinal soft tissues and the vasculature during the osteotomy. FIGURE 34-1 A wide surgical exposure extending several levels above and below the pathologic region is necessary. The procedure begins with complete laminectomies of the affected levels. (Courtesy of the Barrow Neurological Institute.) FIGURE 34-2 Intraoperative photograph showing that the laminae, pedicles, facets, and transverse processes have been removed. The dura and nerve roots have been completely exposed. FIGURE 34-3 Bilateral costotransversectomies extending laterally 10 to 12 cm are undertaken at the affected levels. (Courtesy of the Barrow Neurological Institute.) FIGURE 34-4 The thoracic nerve roots are ligated and sectioned bilaterally to provide a wide corridor of access to the ventral surfaces of the vertebral bodies. Malleable retractors are inserted to displace the pleura and to maintain exposure. A unilateral rod is connected to pedicle screws to partially stabilize the vertebral column during the spondylectomy. FIGURE 34-5 Illustration (A) and intraoperative photograph (B) showing circumferential exposure around the affected levels. Using blunt finger dissection prepares for completion of the spondylectomy. (A, Courtesy of the Barrow Neurological Institute.) Prior to making the osteotomies in the vertebral bodies to remove them en bloc, spinal instrumentation is placed in the adjacent normal vertebrae in anticipation of complete destabilization of the thoracic spine. Pedicle screws are placed bilaterally several levels above and below the levels to be excised (Figs. 34-4 and 34-6). Initially, a unilateral rod is used to secure the pedicle screws provisionally on one side of the spine until the spondylectomy and reconstruction are completed (Figs. 34-4 and 34-7). The second rod is placed after the vertebral bodies have been removed and the graft is inserted.

Complete Spondylectomy for the Excision of Spinal Neoplasms

Historical Background

Historical Background

Treatment Decisions

Treatment Decisions

Surgical Technique

Surgical Technique

General Considerations

Posterolateral Approach for Complete Thoracic Spondylectomy

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree