Continuous Spike Wave of Slow Sleep and Landau-Kleffner Syndrome

Brian Neville

J. Helen Cross

Epileptic encephalopathies are disturbances of cognition, behavior and motor control that occur with epileptic seizures and are attributed to epileptiform activity, which may be subclinical. The definition generally excludes impairments caused by brain damage, either pre-existing or disease related, and those caused by drug treatment. Such encephalopathies can have permanent or reversible, mild or severe, and global or selective effects. This chapter discusses two uncommon epileptic encephalopathies, Landau-Kleffner syndrome (LKS) and continuous spike wave of slow sleep (CSWS). A major focus of the discussion is the degree to which these conditions overlap. CSWS manifests clinically in various ways, including LKS, whereas LKS in a similar clinical form may feature less-florid electroencephalographic (EEG) abnormalities not fulfilling the criteria for CSWS.

LKS was not mentioned in the 1969 and 1981 classifications of the International League Against Epilepsy because encephalopathies were not included (1). The 1989 proposal classifies “acquired epileptic aphasia (LKS)” under “epilepsies and the epileptic syndromes undetermined whether associated with focal and/or generalized seizures”; however, this revision used the clinical and electrical phenomenology of the seizures as the handle for definition when encephalopathy is the main issue (2). CSWS is defined as the association of partial or generalized seizures during sleep and atypical absences during wakefulness with a characteristic EEG pattern of continuous, diffuse spike-and-wave complexes during slow-wave sleep, which is noted after onset of the seizures (2). The relationship between CSWS syndrome, also known as electrical status epilepticus of slow sleep (ESES), and LKS, as well as with the much-less-severe benign epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes (BECTS), has been extensively discussed (3, 4, 5, 6). Children with cognitive or language regression, high rates of centrotemporal or wider epileptiform activity, and normal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans can be placed into a single category. Until our understanding of these disorders improves, LKS may best be regarded as a specific subgroup of CSWS, at least for historical and treatment purposes.

CONTINUOUS SPIKE WAVES OF SLOW SLEEP

Definition

CSWS is characterized by neuropsychological and behavioral changes temporally related to the almost continuous spike-wave activity on electroencephalography that is most prominent and pervasive during slow-wave sleep. It was first described in 1971 as “subclinical status epilepticus” induced by sleep in children (7). Subsequently, other terminology has followed on further descriptions of the syndrome. Although CSWS and ESES are used synonymously, some investigators have proposed that ESES designate the

EEG abnormalities and CSWS the combined electroclinical picture (3); this definition is used in this chapter. The prevalence of CSWS among the epilepsies is unknown, although Morikawa and colleagues (8) found an incidence of 0.5% in 12,854 children reviewed at their center over 10 years. Other investigators (9) have reported similar figures.

EEG abnormalities and CSWS the combined electroclinical picture (3); this definition is used in this chapter. The prevalence of CSWS among the epilepsies is unknown, although Morikawa and colleagues (8) found an incidence of 0.5% in 12,854 children reviewed at their center over 10 years. Other investigators (9) have reported similar figures.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is made primarily on the basis of electrical findings in association with clinical manifestations. Tassinari and colleagues proposed the following characteristics (10):

Neuropsychological impairment seen as global or selective regression of cognitive or expressive functions such as acquired aphasia

Motor impairment in the form of ataxia, dyspraxia, dystonia, or unilateral deficit

Epilepsy with focal and or apparently generalized seizures, tonic-clonic seizures, absences, partial motor seizures, complex partial seizures, or epileptic falls (tonic seizures are not typical)

Electrographic status epilepticus occurring during at least 85% of slow sleep and persisting on three or more records for at least 1 month

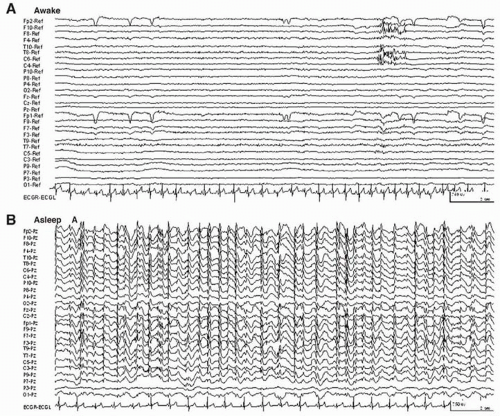

The diagnostic continuous spike-wave discharges occur at 1.5 to 2.5 Hz and persist during slow-wave sleep (Fig. 29.1), particularly in the first sleep cycle (11). Although early investigators required spike-wave activity during 85% of slow sleep for diagnosis, several authors now accept a lower proportion with a clear sleep/wake discrepancy. Previously the abnormality was described as “spatially diffuse”; however, more focal abnormalities have been reported.

Initial reports also proposed that the condition be present over more than three records for at least 1 month (7). Subsequent definitions do not consider duration, which may be related to the timing of the diagnosis.

Early investigations suggested that both sexes are equally affected, but larger collections of case studies show a male preponderance (12).

Clinical Presentation

Even with supposedly similar electrical findings, the clinical presentation remains diverse. Moreover because of considerable overlap it is generally difficult to differentiate CSWS and LKS solely on the basis of clinical features. Some children present with classic regression of language after onset of seizures. In others changes in cognitive performance, varying from the severe to subtle, may be seen within the context of normal or abnormal early developmental progress (8,13,14). In 62% to 74% of patients reported, cognitive development prior to onset was normal (8,13,15), necessitating a high degree of clinical vigilance for diagnosis. Reviewing 209 cases from the literature, Rouselle and Revol (16) classified the neuropsychological presentation into four groups: Group 1 (n=35) had an initially normal neurologic state (except for one child); all children presented with severe epilepsy and little or no neuropsychological deterioration (although cognitive state was often poorly documented). Group 2 (n=33) presented with language deterioration and 28 were classified as having LKS. Group 3 (n=99) included children who were initially neurologically normal and had deterioration of neuropsychological (global or selective) but not language function. Group 4 (n=42) presented with either focal or diffuse brain lesions and unknown clinical manifestations.

The key points of differentiation among the groups were the topographic features of the main electrical focus and the duration of ESES. The neuropsychologically normal children (group 1) had a predominantly rolandic focus and ESES for 6 months. The children with language deterioration (group 2) exhibited a temporal lobe prominence on the electroencephalogram and ESES for 18 months. Children with global deterioration (groups 3 and 4) showed a frontal prominence on the electroencephalogram and ESES for more than 2 years.

Whether the clinical presentation can be correlated with diffuse frontal or temporal predominance of scalp EEG abnormalities during sleep is unclear from the number of cases published. Some researchers propose that acquired aphasia may accompany a temporal prominence of EEG discharges, whereas more global deficits may be linked to diffuse EEG changes with a frontal prominence (16). Analysis of cases involving unilateral pathologic lesions shows that at least some discharges arise focally but propagate rapidly within and between hemispheres, suggesting secondary bilateral synchrony (17,18). Another presentation may involve bilateral pathologic lesions, such as perisylvian polymicrogyria.

Seizures are often not the major feature but often present between 3 and 5 years of age before the diagnosis is made. These are typically focal or generalized motor seizures that tend to occur at night. Drop attacks, such as atonic seizures, occur in approximately 50% of the patients, heralding the appearance of ESES (8). Absence seizures are associated with bursts of spike-wave activity. Some children may have myoclonic absences and generalized nonconvulsive seizures (19,20). Tassinari and associates (10) noted that the severity and frequency of seizures often change when ESES is discovered; to what extent this may be related to the change in EEG pattern that prompts further investigation is unknown. These authors proposed three groups based on seizure patterns: group 1 with rare nocturnal motor seizures (11%); group 2 with unilateral partial motor seizures or generalized tonic-clonic seizures occurring mainly during sleep with absences in wakefulness (44.5%); and group 3 with rare nocturnal seizures but with atypical absences, frequently involving atonic or tonic components, that lead to sudden falls. Negative myoclonus

is common and contributes to the motor impairment (15,21,22).

is common and contributes to the motor impairment (15,21,22).

Etiologic Factors

Genetic factors are unknown although there is one report of monozygotic twins (23) and of familial seizure disorders, including febrile convulsions in 15% of patients (24). Of 71 cases collected for discussion at a 1995 symposium, MRI or computed tomography scan was performed in 58, and 33% of these were abnormal. Children with CSWS are more likely to have abnormal radiologic findings than are children who present with acquired epileptic aphasia, with or without ESES. The most common abnormality is diffuse or unilateral cerebral atrophy, but developmental disorders also figure in a significant proportion of the cases. A particular association has been noted between ESES and multilobar polymicrogyria (18). Atonic seizures (negative myoclonus) were notable in these children, as was the lack of apparent cognitive deterioration at diagnosis, although neuropsychological assessment was difficult.

Kobayashi and colleagues (25) hypothesized two mechanisms of secondary bilateral synchrony that may explain ESES. The first mechanism may involve spread through the corpus callosum. In the second mechanism an initial diffusion of discharges through the corpus callosum may be followed by generalization of discharges through the corticothalamic system. Whether ESES activity in all cases is the result of secondary bilateral synchrony is unclear. Recently, neonatal lesions in the thalamus have been found in cases of CSWS (26,27). The underlying mechanisms leading to ESES are probably complex and poorly understood.

Outcome

CSWS is generally believed to be an age-related phenomenon and prognosis for the EEG abnormality and seizures is relatively good. In most children seizures resolve by the teenage years, preceding (30%), coinciding with (30%) or following (40%) the resolution of ESES. One case report described an adult with nearly continuous spike wave of slow sleep that were present over 4 years (28).

The major long-term morbidity relates to neuropsychological outcome, which is difficult to predict and at best remains guarded. In most cases, a significant, though often partial, improvement occurs after resolution of ESES, and 50% of patients have a nearly average neuropsychological outcome and can lead independent lives (13,29). To what extent cognitive recovery is related to early aggressive treatment (and presumed resolution) of ESES is difficult to determine from the literature; however, trials of aggressive treatment under close supervision may be indicated in an attempt to normalize the EEG pattern when cognitive decline is documented.

LANDAU-KLEFFNER SYNDROME

An uncommon condition, LKS is probably the clearest illustration of the acquired epileptic encephalopathies. A “classical” definition has been articulated since the original description in 1957 (30), but several of the first six patients had wider impairments than some authorities might accept. In LKS, normal development including language for at least the first 2 years of life is followed by loss of language, particularly speech comprehension, in association with partial epilepsy of centrotemporal origin. In 20% to 30% of children, no clinical seizures are obvious at presentation but a typical EEG abnormality is enhanced during sleep. MRI scanning shows negative results. Even with these strict criteria, however, children with LKS commonly have additional impairments that are often more amenable to treatment than is the aphasia. Consequently, we prefer a broad definition with acquired aphasia being an early feature and the inclusion of additional attention deficit, hyperactivity, motor organization problems, features of autistic spectrum disorder, and global cognitive regression. Some authorities choose to restrict use of the term LKS to children who retain social responsiveness and regard the development of autism as a different condition (31). We include children with these disorders if they otherwise satisfy the criteria for LKS. We recognize two variant forms: one with mild primary language delay and typical regression after 2 years of age and a second variant with a lesion, usually temporal. Children younger than 2 years of age with regression are excluded despite evidence of concurrent epileptiform activity.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree