Controversies, Myths, and Realities Regarding the Surgical Treatment of Cervical Spondylotic Myelopathy with a Special Focus on Laminoplasty

Brett A. Freedman

John G. Heller

Spondylosis is the most common cause for myelopathy/spinal cord injury in patients over the age of 50. It is most easily thought of as “gray hair of the neck,” which is virtually ubiquitous in our aging population. Spondylosis is manifest radiographically as disk space height loss, end plate sclerosis, and osteophyte formation. These anatomic changes may contribute to stenosis of the spinal canal and neuroforamen. In a subset of individuals, the narrowing may lead to spinal cord compression and clinical manifestations of myelopathy. Since the natural history of myelopathy is one of stepwise progression for 75% of patients, spinal cord decompression is in order once significant signs and symptoms are apparent (1,2). At issue in this chapter is whether and when such a surgical decompression requires concomitant fusion.

In North America, the most common surgical procedure performed for cervical spondylotic myelopathy (CSM) is anterior decompression and fusion (ADF) via anterior cervical discectomy and fusion or corpectomy and fusion. In the case of single- or two-level spinal cord compromise, ADF is held to be the superior surgical approach. It provides reliable, direct decompression through removal of the ventral compressive lesions. The procedure has been used effectively for more than a half century (3,4). More recently, cervical disk replacement has been shown to be effective in treating single-level cervical myelopathy due to central disk herniations (5). Thus, we feel there is little controversy that ADF is the appropriate treatment for one- and two-level cervical myelopathy arising from ventral spinal cord compression. It is the de facto standard of care for one- and two-level compressive myelopathy.

Controversy exists in selecting the best treatment for multilevel compressive myelopathy. While there are numerous subtle modifications, in general, there are three basic approaches to the treatment of multilevel compressive myelopathy—laminectomy with or without fusion, ADF, and laminoplasty. Laminectomy was the original treatment for multilevel CSM (6). While it provides adequate decompression in the majority of cases, it is has a risk of poor long-term outcomes, due to progressive kyphosis, instability, and recurrent ventral spinal cord compression with worsening myelopathy. To address this shortcoming, surgeons have added segmental instrumentation and fusion to such laminectomies (7,8). As long as the fusion is successful, this more involved procedure does reduce the incidence of kyphosis, iatrogenic instability, and late progression of myelopathy. But like all multilevel fusion procedures, it invites the potential complications inherent to segmental instrumentation and graft healing (7, 8 and 9). Like the multilevel ventral procedures, motion is sacrificed in favor of neurologic recovery.

Dorsal operations, like laminectomy with or without fusion, decompress the spinal cord through indirect means as the spinal cord migrates dorsally when the lamina are removed. This therefore requires a lordotic or at a minimum neutral or slightly kyphotic (<5 to 10 degrees) cervical sagittal alignment (10). If this condition is not met, or when there is mobile listhesis, laminectomy alone leads to inferior neurologic recovery rates. The addition of an instrumented fusion can overcome these geometric and stability constraints. However, in doing so, there is risk of cervical root palsy due to iatrogenic foraminal stenosis (9).

Nonetheless, while laminectomy alone has fallen into disfavor, laminectomy with dorsal spinal fusion remains a popular treatment option for multilevel CSM. Unfortunately, the literature regarding this technique is sparse, specifically regarding direct comparison to the other two primary approaches to CSM.

Nonetheless, while laminectomy alone has fallen into disfavor, laminectomy with dorsal spinal fusion remains a popular treatment option for multilevel CSM. Unfortunately, the literature regarding this technique is sparse, specifically regarding direct comparison to the other two primary approaches to CSM.

In the late 1950s, Smith and Robinson and Cloward pioneered the concept of ADF (3,4). The techniques have since been refined and improved to safely tackle multilevel CSM. The addition of plate fixation greatly improved fusion rates and reduced graft-related complications like migration, extrusion, and subsidence (11, 12 and 13). Nevertheless, the nonunion rate remains proportional to the number of levels treated and continues to be a significant complication of ADF (14). Additionally, the ventral exposure of multiple spinal levels is associated with its own morbidity, which is amplified in the elderly patients who most commonly undergo this procedure. These morbidities may include swallowing difficulty, airway compromise, and stroke from carotid artery disease or vertebral artery injury. In addition, patients undergoing multilevel ADF are frequently placed in rigid postoperative collars, even halo vests on occasion, which are a significant impediment to activities of daily living in the short term. Furthermore, some patients receive ventral and dorsal fusion procedures, exposing patients to the risks and morbidities of both approaches. Fortunately, the more complex circumferential operations are reserved for a subset of patients with particularly challenging circumstances. Lastly, the acute stiffening of multiple cervical spinal segments results in point loading of the adjacent nonfused disks above and below, theoretically accelerating adjacent segment disease, with a potential 10-year greater than 25% reoperation rate.

To place in perspective the significance patients place on surgical morbidity and postoperative activity restrictions (i.e., immobilization), Masaki et al. (15) reported that when counseled that neurologic recovery rate was superior for ADF over laminoplasty, but morbidity and postoperative immobilization was worse for ADF, elderly patients chose laminoplasty by a ratio of 2:1. Thus, weighing the overall risks and benefits of the operations for CSM (laminectomy with/without fusion and ADF), which predated laminoplasty, these surgical strategies did not provide an ideal solution to the challenging problem of CSM.

When critical stenosis exists over three or more levels, there is great regional disparity on how best to proceed. In North America and Europe, the preferred choice continues to be ventral or dorsal decompression and fusion, while in Japan, laminoplasty has become the prevalent option. Over 75% of the clinical publications on laminoplasty come from Japan. The procedure evolved there, while ventral decompression methods were under refinement in North America and Europe (16,17). The creators of these procedures sought to find a surgical treatment for compressive myelopathy, which could provide better neurologic recovery than laminectomy, while avoiding postoperative instability issues.

Japan was a natural site for the introduction and development of surgical options for CSM, such as the laminoplasty concept. Above and beyond the prevalence of spondylosis, it has one of the highest rates of ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament (OPLL) and developmental spinal canal stenosis in the world. Furthermore, its surgical training programs are very centralized. Starting in the mid-1970s, university hospitals in Japan progressively utilized laminoplasty as a primary treatment for compressive myelopathy from all etiologies. While neurologic recovery has been repeatedly shown to be equivalent for laminoplasty, laminectomy and fusion, and ADF in well-selected patients, the procedure has not gained similarly wide acceptance in the United States and Europe. The focus of the remaining portion of this chapter is to sort through some of the myths surrounding laminoplasty and provide an evidenced-based understanding of the efficacy and complication profile of laminoplasty for the treatment of compressive myelopathy.

The indications for laminoplasty are similar to those for laminectomy with or without fusion and ADF. They include compressive myelopathy involving three or more disk levels, salvage for failed ADF and primary treatment in poor bone healers (i.e., smokers and patients with metabolic bone diseases). Laminoplasty is an especially good choice in patients with developmentally narrow spinal canals (midbody AP diameter <12 mm), since expanding the dorsal arch directly treats the underlying primary pathology. Over 50% of patients undergoing ADF for CSM have relative (<13 mm) or absolute (<10 mm) developmental spinal canal stenosis (18). Patients with developmental stenosis tend to manifest myelopathy earlier in life. Since laminoplasty does not intentionally fuse the operated segments, it is in fact the only “motion-preserving” technique for addressing multilevel CSM (approved in the United States), which is another consideration in selecting a surgical approach to CSM.

It should be noted that there is controversy related to laminoplasty and its ability to preserve cervical range of motion (ROM). Is it actually optimal to preserve motion in patients with MCM? Some contend that dynamic stresses on the spinal cord are important pathogenic factors (19,20). This position is taken by those who maintain that the reduced motion associated with a multilevel fusion favors the possibility of neurologic improvement. We feel motion preservation is a favorable aspect of laminoplasty based on the results reported by Buchowski et al. following total disk replacements in patients with myelopathy; our own personal experience and the lack of strong evidence to the contrary suggesting that ROM is negative (5,21, 22 and 23). In addition, it has been shown repeatedly that recurrent neurologic compromise due to adjacent segment degeneration will follow fusion procedures (the converse to motion preservation) at a predictable rate (22,24,25). Nevertheless, in the absence of randomized trials comparing laminoplasty and laminectomy/fusion or ADF, the impact of motion preservation remains a point of discussion. Despite this limitation in the current knowledge base, most laminoplasty surgeons specifically seek to preserve motion following laminoplasty. In fact, a primary advantage of instrumented laminoplasty is immediate hinge stabilization, which permits early active ROM exercises and less postoperative immobilization, with the goal of maximizing motion preservation (23).

As with all procedures, there are absolute contraindications, which include (a) fixed kyphosis (>10 to 15 degrees), (b) epidural fibrosis (i.e., following infection, previous dorsal spinal surgery, or ossification of the ligamentum flavum), (c) large “hill-shaped” focal ventral lesions that

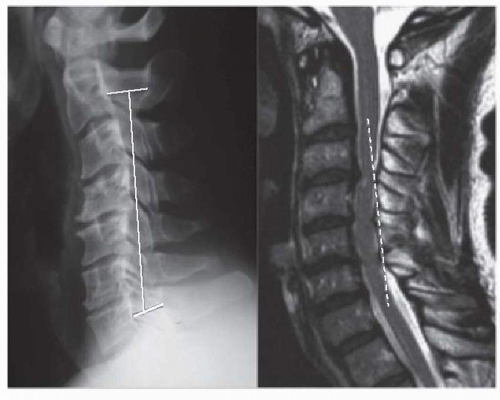

occupy more than 50% to 60% of the AP canal diameter, and (d) axial neck pain as the patient’s primary clinical complaint. Fujiyoshi et al. (26) have reported on a single, easy-to-perform radiographic or MRI line that can be used to quickly eliminate the first and third contraindications. Their “K-line” is constructed by connecting the midpoints of the spinal canal on upright lateral radiograph or midline sagittal MRI of C2 and C7. If all of the compressive pathology lies ventral to this line, the patient is termed K-line positive and laminoplasty is indicated. If ventral compressive structures intersect this line, the patient is K-line negative (Fig. 130.1). In K-line positive cases, the average neurologic recovery rate following laminoplasty was 66% compared to 19% when it is negative (26). Likewise, 63% of K-line negative patients had continuous contact between the spinal cord and ventral lesions following laminoplasty, as measured by intraoperative ultrasound, versus none of the K-line positive patients. Tani et al. (27) showed that when the occupation ratio (AP length of ventral lesion/AP canal diameter at same level) is greater than 50% (average was 65% in their study), the neurologic recovery rates are unacceptably poorer for laminoplasty versus ADF, with 33% actually worsening following laminoplasty (27). Masaki et al. (15) have shown that segmental hypermobility at the level of maximum preoperative compression also leads to poorer outcomes with laminoplasty. This study also reconfirmed that high occupation ratio is a poor prognosticator for neurologic recovery after laminoplasty, average 56%. The results of Kawakami et al. (28) suggest that hypermobility is less detrimental to outcome than occupation ratio, as hypermobility had no impact on the 67 patients they studied (28). Thus, there are contraindications for laminoplasty. But the majority of patients with compressive myelopathy over three or more levels are candidates for laminoplasty.

occupy more than 50% to 60% of the AP canal diameter, and (d) axial neck pain as the patient’s primary clinical complaint. Fujiyoshi et al. (26) have reported on a single, easy-to-perform radiographic or MRI line that can be used to quickly eliminate the first and third contraindications. Their “K-line” is constructed by connecting the midpoints of the spinal canal on upright lateral radiograph or midline sagittal MRI of C2 and C7. If all of the compressive pathology lies ventral to this line, the patient is termed K-line positive and laminoplasty is indicated. If ventral compressive structures intersect this line, the patient is K-line negative (Fig. 130.1). In K-line positive cases, the average neurologic recovery rate following laminoplasty was 66% compared to 19% when it is negative (26). Likewise, 63% of K-line negative patients had continuous contact between the spinal cord and ventral lesions following laminoplasty, as measured by intraoperative ultrasound, versus none of the K-line positive patients. Tani et al. (27) showed that when the occupation ratio (AP length of ventral lesion/AP canal diameter at same level) is greater than 50% (average was 65% in their study), the neurologic recovery rates are unacceptably poorer for laminoplasty versus ADF, with 33% actually worsening following laminoplasty (27). Masaki et al. (15) have shown that segmental hypermobility at the level of maximum preoperative compression also leads to poorer outcomes with laminoplasty. This study also reconfirmed that high occupation ratio is a poor prognosticator for neurologic recovery after laminoplasty, average 56%. The results of Kawakami et al. (28) suggest that hypermobility is less detrimental to outcome than occupation ratio, as hypermobility had no impact on the 67 patients they studied (28). Thus, there are contraindications for laminoplasty. But the majority of patients with compressive myelopathy over three or more levels are candidates for laminoplasty.

When evaluating the overall efficacy of a surgical procedure in the treatment of CSM, five outcome measures stand out (Table 130.1). Recently, the authors performed a systematic analysis of the English literature regarding laminoplasty to accurately assess the results of laminoplasty in terms of these five outcomes (29). We identified and reviewed 75 articles published prior to November 2008, which reported results of laminoplasty with at least a 12-month follow-up. The following paragraphs will summarize our analysis. The impetus for the study was a contradiction between favorable personal experience and a general disinterest in laminoplasty within the United States, which is often fueled by reports of worse outcomes following laminoplasty versus the more accepted ADF approaches. Our review of the literature identified the reality behind several prevailing myths about laminoplasty outcomes.

Since CSM is a progressive neurologic disorder, the most important outcome to assess is neurologic recovery. One of the advantages of the fact that 78% of the literature reporting clinical outcomes from laminoplasty comes from Japan is that a single neurologic outcome assessment tool has been used in the overwhelming majority of clinical studies. The Japanese Orthopaedic Association (JOA) score is a 6-part, 17-point scoring system, which assesses fine motor skills, ambulation, and sensation in the upper and lower extremity as well as the trunk and bladder function (30) (Table 130.2). Hirabayashi in his original reports of laminoplasty outcomes set the standard for assessing recovery rate as the quotient of (postoperative JOA score—preoperative JOA score)/

(17—preoperative JOA score) (16). Thus, recovery is measured as the percentage improvement from baseline to the complete normal state. Since myelopathy is often a disease of slow stepwise progression, in which symptoms are present for months or years prior to surgical intervention, and it is a disease most common to the elderly, it should not be a surprise that achieving 100% neurologic recovery is rare. In fact, the average postoperative JOA score following laminoplasty, which was not significantly different than ADF, was 13.6 in our study. This equates to a median 58% neurologic recovery. To lend some perspective to the reader, it should be noted that a patient with a score of 14 would be someone with minimal extremity sensory loss, mildly reduced manual dexterity, and able to walk without support but slowly in the community with normal bladder function—in short, a pretty functional elderly person. Thus, neurologic recovery following decompressive surgery for myelopathy is almost always incomplete, regardless of the surgical approach, but still quite favorable following laminoplasty and ADF.

(17—preoperative JOA score) (16). Thus, recovery is measured as the percentage improvement from baseline to the complete normal state. Since myelopathy is often a disease of slow stepwise progression, in which symptoms are present for months or years prior to surgical intervention, and it is a disease most common to the elderly, it should not be a surprise that achieving 100% neurologic recovery is rare. In fact, the average postoperative JOA score following laminoplasty, which was not significantly different than ADF, was 13.6 in our study. This equates to a median 58% neurologic recovery. To lend some perspective to the reader, it should be noted that a patient with a score of 14 would be someone with minimal extremity sensory loss, mildly reduced manual dexterity, and able to walk without support but slowly in the community with normal bladder function—in short, a pretty functional elderly person. Thus, neurologic recovery following decompressive surgery for myelopathy is almost always incomplete, regardless of the surgical approach, but still quite favorable following laminoplasty and ADF.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree