4 Cranial Nerve II

Optic Nerve and Visual System

Intraocular Optic Nerve

Clinical Vignette

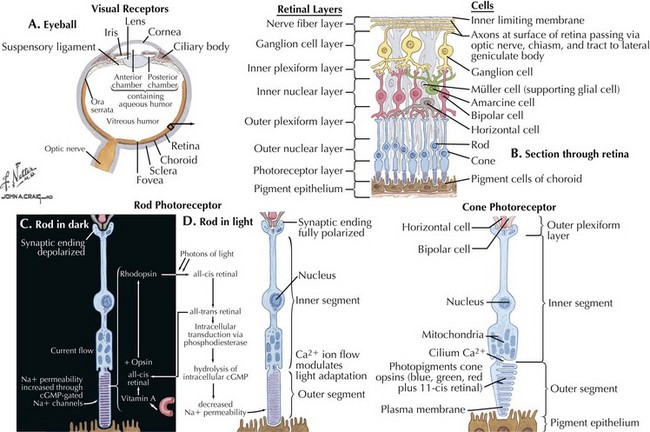

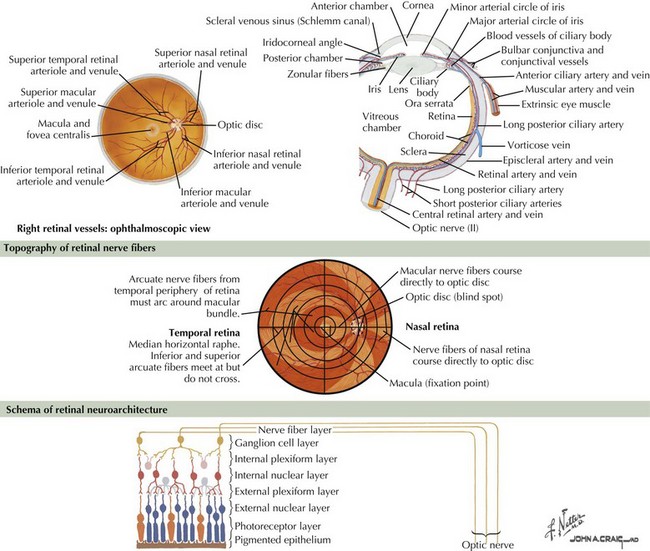

The optic nerve is not a peripheral nerve but rather a central nervous system (CNS) tract containing central myelin formed by oligodendrocytes. It is composed of long axons, whose cell bodies comprise the ganglion cell layer of the inner retina (Figs. 4-1 and 4-2). The axons run in the retina’s nerve fiber layer to gather at the optic disk.

The optic nerve nominally begins when the axons of the ganglion cells (the nerve fiber layer of the retina) turn 90°, changing orientation from horizontal along the inner retinal surface to vertical, passing through the outer retina via the scleral canal (Fig. 4-3). The gathering of axons at the canal forms the optic disk (also, optic nerve head) of the fundus. Myelin is usually absent from the nerve fiber layer where the nerve exits the globe.

Clinical Presentations

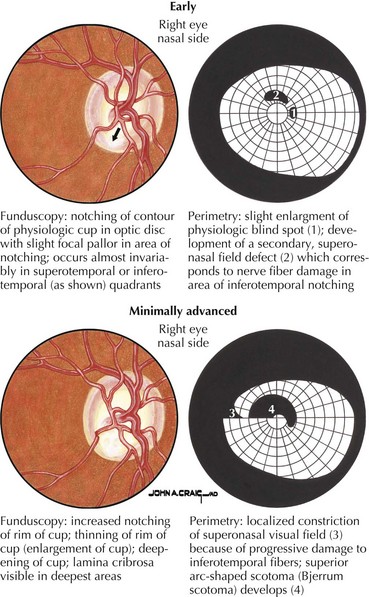

Primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG) is a chronic, progressive, degenerative disease of the optic nerve. Its usual hallmark is high intraocular pressure (IOP; above 21 mm Hg), but glaucoma without high IOP (normal pressure or low-tension glaucoma) is occasionally seen, especially in the elderly. The typical optic nerve finding is cupping atrophy (i.e., enlargement of the disk’s central cup as nerve fibers are lost), coupled by progressive visual field loss that often starts nasally, progresses superiorly and inferiorly, and finally extinguishes the central and temporal fields (Fig. 4-4). POAG is usually bilateral and asymmetric and the visual loss is permanent. The time course is measured in years, and because of the slow pace and the late involvement of the central field, patients may remain asymptomatic until the disease is quite advanced. It is essential that all standard eye examinations include screening IOP measurements and optic disk inspection.

CRAO, BRAO, and TMVL may also serve as a warning sign of impending hemispheric stroke. Identification and treatment of the embolic source, if one can be identified, becomes the main focus of therapy after the window for acute treatment of the involved eye has passed. CRAO is often a sign of carotid stenosis, the appropriate management of which will significantly reduce long-term stroke risk (see Chapter 55, “Ischemic Stroke”). Heart embolism is another cause and a full stroke investigation is usually required. Nevertheless, up to 40% of cases remain without a definite identifiable cause with the presumed mechanism relating to intrinsic narrowing of the retinal artery due to atherosclerosis or, less commonly, other arteritides or compression.

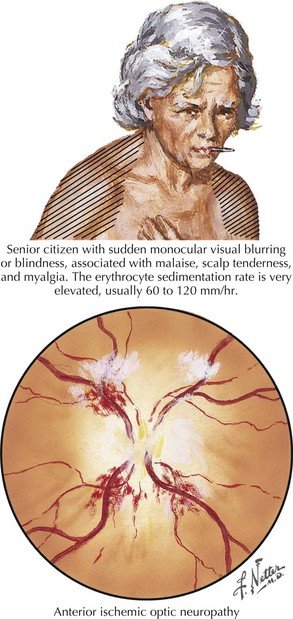

Anterior ischemic optic neuropathy can be divided into nonarteritic and arteritic (associated with temporal arteritis [TA]) and is caused by loss of blood flow in the short posterior ciliary arteries. Patients usually experience sudden and severe painless monocular visual loss, often on awakening. Examination classically reveals an altitudinal (superior or inferior) visual field loss, with a unilaterally swollen, hemorrhagic disk (Fig. 4-5). The disk loses its swelling and becomes pale within weeks. The visual loss in most cases does not change following the event but 20% may show measurable change for better or worse over days. In contrast to retinal artery occlusions, embolic AION is extremely rare. In most cases, AION occurs in middle-aged individuals who have a congenitally small, elevated (“crowded”) optic disk, or in those with one or more vascular disease risk factors, such as diabetes, hypertension, or sleep apnea. In these cases, a transient fall in blood pressure causes hypoperfusion of the posterior ciliary circulation and subsequent ischemic damage to the optic nerve head.

Papilledema (see Fig. 1-6) is bilateral optic nerve elevation and expansion due to high intracranial pressure (ICP). In mild cases, patients may have no visual symptoms. Moderate papilledema is typically accompanied by transient binocular visual obscurations, either spontaneously or during coughing, straining, or abrupt postural change. Other symptoms of high ICP may be present and include headaches (worse with recumbency) and diplopia (resulting from nonlocalizing abducens palsy; see Chapter 5). When visual loss occurs, it starts with blind spot enlargement (see Fig. 1-6), a nonspecific and often reversible change. Visual field loss resembling that of glaucoma can ensue, often over a period of many weeks. However, papilledema due to very high ICP can progress rapidly, with severe permanent visual loss within days.

Many pathophysiological mechanisms are associated with papilledema, including CNS tumor with mass effect or edema, obstructive hydrocephalus, meningitis, certain medications (e.g., tetracycline or vitamin A), and intracranial venous thrombosis or obstruction. Papilledema is occasionally seen without explanation in obese women of childbearing age and is then termed idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH; also, pseudotumor cerebri; see Chapter 11). Treatment involves only weight loss if the condition is mild and there is no evidence of progressive visual loss or debilitating headache. In progressive IIH, in addition to weight loss, carbonic anhydrase inhibitors such as acetazolamide (typically 1–2 g/day in divided doses) are used to reduce cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) production and optic nerve edema. When medical treatment fails, two surgical options exist: optic nerve sheath fenestration or CSF shunting either with lumboperitoneal or ventriculoperitoneal shunts.

Orbital and Intracanalicular Optic Nerve

Clinical Vignette

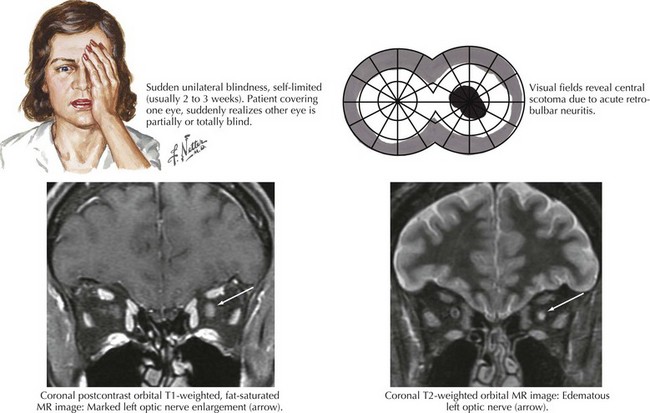

Multiple sclerosis (see Chapter 46), however, remains the chief cause of orbital optic nerve disease and is the initial manifestation in approximately 20% of patients. An additional 20% will eventually experience it throughout the course of the disease. It is estimated that more than 90% of patients suffering “isolated” optic neuritis will eventually receive a diagnosis of MS. Diagnostic testing in optic neuritis naturally mirrors that for MS, with brain MRI and CSF analysis being the primary tools.

Clinical Presentations

Optic neuritis is the clinical syndrome of subacute painful, monocular visual loss. The pain often precedes visual loss by a day or more and is a periorbital ache made worse with eye movements. Ensuing visual loss is often sudden and severe, with perceived worsening over several days. The degree of visual field loss varies, but a central scotoma is the classic finding (Fig. 4-6). Examination may also demonstrate loss of central acuity, contrast sensitivity, and color perception in the affected eye.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree