Cranial Nerve Symptoms

Michael Ronthal

Sean I. Savitz

▪ INTRODUCTION

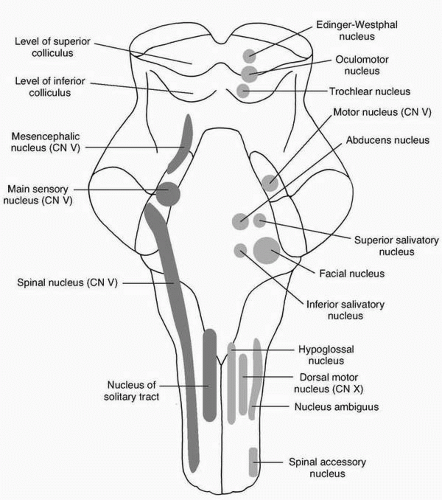

This chapter covers common symptoms referable to dysfunction of the cranial nerves or their proximal or distal connections. For certain symptoms, such as dizziness, for example, the vestibular nerve may be the site of pathology or the upper neuron pathways within the brainstem/cerebellum controlling the vestibular system. For each symptom, an approach to the evaluation of the cranial nerves involved and the differential diagnosis are provided. Overall, the nuclei for cranial nerves II to XII can be found scattered throughout the brainstem (Fig. 1.1). Specific symptoms are caused by disorders of the upper brainstem (visual), middle brainstem (facial), and lower brainstem (dysphagia). Details of each symptom are described in the following sections.

▪ DOUBLE VISION

The normal upper motor neuron (UMN) control of eye movements results in smooth conjugate gaze. Diplopia, or double vision, implies a defect in the yoking mechanism of the eyes, and that in turn implies a defect in the lower motor neuron (LMN) mechanism.

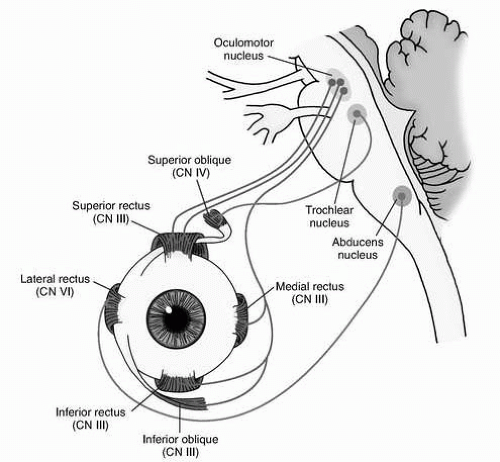

The LMN stretches from and includes the ocular motor nuclei; the third, fourth, and sixth cranial nerves; the neuromuscular junctions; and the external ocular muscles.

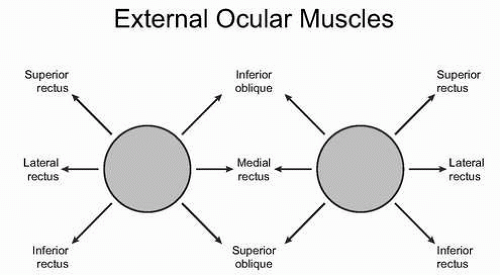

Each muscle has a specific direction of pull, and weakness secondary to a defect somewhere along the line results in misalignment of the eyeball with resultant diplopia when the patient looks in the direction of gaze controlled by that muscle. The lateral or external rectus is applied by the sixth nerve on each side. The superior oblique is supplied by the fourth, or trochlear, nerve. All other muscles are innervated by the third nerve, which also supplies the pupil and the levator of the eyelid.

Clinical Examination

Patients may clearly describe a symptom as double vision, or they may simply complain of blurriness. To sort this out, two key questions should be asked: “What do you see?” and “What happens if you close one eye?” Resolution of the blurriness if one or the other eye is closed suggests that the true symptom is diplopia.

The next step in analysis is to sort out monocular from binocular diplopia. If vision is normal when using one eye only yet blurred or doubled when using the alternate eye only, the diagnosis is monocular diplopia, which implies a local ophthalmological problem rather than a neurological one.

If the diplopia is truly binocular, the examination should sort out which eye is involved and which muscle is weak.

A test object, for example, a finger or light source, is held before the patient in the prime directions of gaze. Horizontally, it will be to left and right, but for vertical gaze, given the direction

of pull of the muscles, as shown in Figure 1.2, the object is held not directly vertically but off to one side. Figure 1.3 shows the distribution of cranial nerves (CNs) VI, IV, and III.

of pull of the muscles, as shown in Figure 1.2, the object is held not directly vertically but off to one side. Figure 1.3 shows the distribution of cranial nerves (CNs) VI, IV, and III.

The “false” object, that is, the object subtended by the weak eye, is always external to the “true” object. It remains to sort out which object is indeed “false.” This can be ascertained by closing one eye and asking which image disappears, or, better still by using a red glass. The red glass is, by convention, held over the right eye. Objects seen with the right eye will be red, those with the left eye normal in color. In the absence of diplopia the object will appear single and pink. Each direction of gaze is tested and the weak muscle diagnosed.

Once diplopia in a specific direction of gaze is established, the test object should be held in position for a minute or two to establish or deny a fatigue or myasthenic response. If the two perceived objects separate progressively, the diagnosis is ocular myasthenia.

Third Nerve Palsy

A third nerve lesion may be complete or partial. A partial deficit, that is, when only some of the muscles innervated by the nerve are weak, suggests that the lesion is in either the midbrain or retrobulbar area. The third nerve nucleus is large, and pathology such as tiny infarctions can affect only part of the nerve. From the nucleus itself, strands of nerve course ventrally through the brainstem; a partial lesion of these strands is termed a fascicular third nerve palsy.

From the ventral brainstem the nerve courses forward to the cavernous sinus and through it to the superior orbital fissure, where it divides into a superior division to levator palpebrae and superior rectus and an inferior division that then breaks up to supply the various extraocular muscles. Local pathological processes in the orbit should be excluded by imaging, and activity tests in the blood should be done to exclude an inflammatory cause such as arteritis.

A lesion along the course of the third nerve at the base of the brain usually results in a complete palsy with ptosis, sparing of lateral movement of the eyeball, and intorsion movement of the eyeball when looking downward past the horizontal meridian. The differential diagnosis includes a posterior communicating aneurysm compressing the nerve or a meningitic process. If the pupil is spared, the cause is likely diabetes with microvascular infarction (“pupil-sparing third”). Imaging, including angiography and a spinal tap, if there is no aneurysm, are indicated.

Fourth Nerve Palsy

Diplopia will be present when looking down and inward. If the head is tilted to one or the other side, it may be possible to see misalignment of the eyeballs.

The nerve is thin and has a tortuous course, emerging from the dorsal brainstem and coursing around it before passing anteriorly at the base in the direction of the orbit. Usually the cause of a fourth nerve lesion is obscure; it could be traumatic, infective, postinfective, or microvascular in origin.

Sixth Nerve Palsy

Diplopia is present on lateral gaze. The causes of a sixth nerve palsy are legion, and its presence, as with any of the previously described syndromes, triggers extensive imaging, blood studies, and a spinal fluid study.

Neuromuscular Junction

Myasthenia results in fluctuating diplopia and may or may not be associated with weakness of other somatic muscles. Reversal of an overt external ocular muscle palsy or just diplopia by an intravenous injection of edrophonium confirms the diagnosis. The drug should be administered with electrocardiographic control, and atropine should be at the bedside as a muscarinic antidote in case of severe bradycardia. The response for a positive test should be dramatic and not equivocal.

Botulism paralyzes the eye muscles and can also affect the pupil, a sign that is never seen in myasthenia. There is often a history of ingestion of imperfectly preserved food.

Ocular Muscles

Orbital myositis is an inflammatory myopathy affecting the extraocular muscles. Pain on eye movement is the clue, and imaging of the orbit may show swollen or edematous muscles. It responds to steroids.

▪ VISUAL LOSS

As with the analysis of diplopia, loss of vision may be binocular, which implies a retrobulbar problem, or monocular, which implies a pathological condition locally in the eye or optic nerve. Retrobulbar problems affect the fields of vision of both eyes and have specific patterns.

Clinical Examination

If we are to evaluate visual loss, we must have reliable methods to measure vision. A reading card is used for near vision, and for distant vision a Snellen chart suffices. Refractive errors should be compensated for with appropriate spectacles; if these are not available, a pinhole eliminates refractive error. Subtle visual loss can be appreciated by testing color vision—a red object looks red with the normal eye or field and washed-out pink or black in the defective areas.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree