aValues are approximate.

The MCT diet has been used since the 1970s. This diet provides large quantities of this highly ketogenic oil in order to free up more carbohydrates, and this in turn improves tolerability. The MCT diet was studied in a prospective, controlled, randomized manner by Dr. Neal and colleagues from London in 2008, and although the classic KD led to higher serum ketone levels, fatigue (at 3 months), and mineral deficiencies, there was no difference in growth, efficacy, and overall tolerability (5,25,26). There may be some benefit to dyslipidemia (27). The MCT diet is mostly used in the United Kingdom and Canada at this time.

The LGIT was first published by Dr. Thiele and colleagues from Boston in 2005, based on previously anecdotal reports of excessive carbohydrates (at times from cheating) leading to immediate seizure breakthroughs (28). This diet targets glucose by providing carbohydrates with glycemic indices <50 in order to maintain stable blood glucose levels (28). Although serum ketones do increase, changes are usually minimal. The LGIT is started as an outpatient without a fasting period. An update in 2009 from the same group includes 76 children, of which 50% of those remaining on the diet at 3 months had >50% seizure reduction (7). Nearly one-quarter found the LGIT restrictive and stopped this diet for that reason. Recent studies have described benefits for children with tuberous sclerosis complex and Angelman syndrome (29,30).

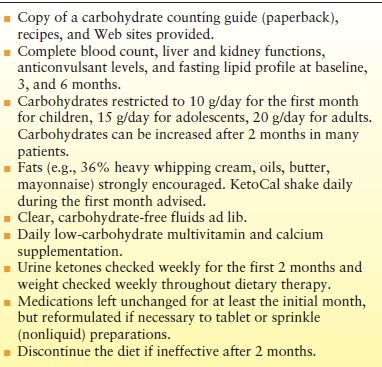

The fourth therapeutic diet, the MAD, was first published by our group in 2003 (31). The MAD is also started on an outpatient without a fast, but does not restrict calories, fluid, or protein (Table 70.2). Carbohydrates are restricted to 10 g/day (children) or 20 g/day (adults), and fats are strongly encouraged in order to maintain ketosis. When analyzed, the MAD mimics a 1:1 ketogenic ratio. To our knowledge, there are now 33 publications that detail the use of the MAD in children and adults, with 207 (46%) of 452 total subjects having >50% seizure reduction after 6 months of which 108 (22%) had >90% improvement. These results are quite similar to findings in patients treated with the KD. One recent publication suggests that using one of the KD formulas (KetoCal) during the initial month may in fact boost the efficacy of the MAD by providing additional fat sources (6). Children can be switched from the MAD to the KD, with 30% of those switched having additional benefit, especially if their underlying condition was myoclonic astatic epilepsy (Doose syndrome) (32). Long-term outcomes on the MAD after 12 months appear similar to the short-term benefits as well (33). The MAD may also be especially useful for centers in developing countries with limited resources to implement the classic KD (34). At our center, the MAD has largely supplanted the KD for adolescents and adults nowadays.

Table 70.2 Modified Atkins Diet Protocol 2014

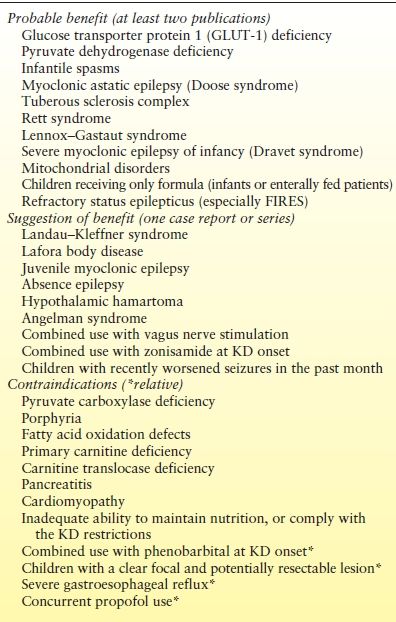

INDICATIONS

For many years, as evidence for its efficacy grew, the KD was solely indicated for “children with intractable epilepsy” in chapters such as this and review articles. There were no particular indications mentioned with the exception of GLUT-1 (glucose transporter-1) deficiency and pyruvate dehydrogenase deficiency. As studies have demonstrated the benefits of the KD for specific conditions, this concept has changed. The 2009 Consensus Statement focused on indications and provided a list of “indications” for the KD is available (Table 70.3) (4). These included myoclonic astatic epilepsy, tuberous sclerosis complex, Rett syndrome, infantile spasms, Dravet syndrome, and children receiving only formula (4). Since 2009, the data justifying the strong benefit of the KD for Dravet syndrome, myoclonic astatic epilepsy (Doose syndrome), and mitochondrial disorders have continued to increase (35–37).

Table 70.3 Potential Indications and Contraindications for Dietary Therapy

Pediatric patients with infantile spasms may be the fastest growing population to be started on the KD, perhaps due to the combination of its efficacy as well as ease of use with myriad ketogenic formulas widely available worldwide. Several studies have been published on the use of the KD for infantile spasms since 2001. The largest to date included 104 infants, of which 64% had at least a >50% decrease in their spasms within 6 months of treatment, including 38 (37%) who became spasm free for at least 6 months (38). As a result of this growing evidence for intractable infantile spasms, our center has used the KD in children for new- onset infantile spasms (if the family brings the child in within 2 weeks after seizure onset) (10). To date, 10 out of 24 (42%) infants became spasm free within 2 weeks of treatment. Additional information about the use of the KD for new-onset infantile spasms is available through the Carson Harris Foundation.

New indications continue to be studied. One exciting development has been the recent attention to the use of the KD for refractory status epilepticus (39). The epilepsy condition entitled FIRES (febrile infection–related epilepsy syndrome), often difficult to control with poor outcomes, appears to be very susceptible to the KD (40). Providing the KD as a formula through a nasogastric tube to a patient in an intensive care unit with status epilepticus is a very feasible option, with successful results typically described within 7 to 10 days (39). Prospective multicenter studies for refractory status epilepticus are under way. Other conditions recently reported as responding to dietary therapy in recent years include absence epilepsy, juvenile myoclonic epilepsy, Sturge–Weber syndrome, and hypothalamic hamartoma.

Contraindications to the diet do exist and are primarily metabolic in nature. Children with malnourishment, primary carnitine deficiency, carnitine translocase deficiency, porphyria, pancreatitis, fatty acid oxidation defects, and cardiomyopathy should not be started on the KD (4). In addition, families with poor oral intake, vegan food preferences, dyslipidemia, parent noncompliance, and epilepsy surgery candidates [for whom surgery is more likely to lead to seizure freedom (41)] should receive detailed counseling on the KD prior to its implementation. One study suggested that those receiving phenobarbital at KD onset were less likely to respond as well (18).

ADULTS

Although described in the 1930s, KD treatment in adults with intractable epilepsy has more recently rarely been utilized and infrequently studied (8). Largely as a result of the emergence of the MAD as a less restrictive alternative, there has been a large amount of interest in this population and emergence of adult epilepsy diet centers (including in Baltimore and London) in the last few years. Evidence would suggest that when effective, the MAD will lead to seizure reduction within several weeks, thus the potential restrictiveness (if ineffective) need only be short-lived (15). Dietary therapy has been studied for adults with juvenile myoclonic epilepsy and refractory status epilepticus (39,42). The benefits of weight loss for obese patients with epilepsy may also be an additional valuable outcome. A prospective, randomized trial evaluating the MAD in combination with KetoCal [in a manner similar to a study in children (6)] is enrolling patients at our institution.

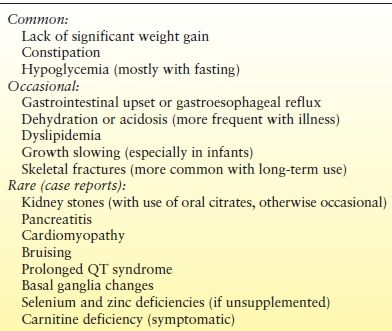

SIDE EFFECTS

Side effects do occur with dietary therapies as these treatments are neither alternative nor designed to be healthy (Table 70.4). They include constipation (improved with fiber supplements), acidosis (increased with illness), gastrointestinal upset and reflux, and lack of significant weight gain (occasionally weight loss) (13). Children who do not receive adequate vitamin and calcium supplementation will become deficient, and this must be avoided. At this time, the only mandatory supplements suggested in the Consensus Statement include an oral multivitamin, calcium, and vitamin D (4).

Table 70.4 Reported Side Effects of the KETOGENIC DIET

Less common, but potentially more serious side effects include dyslipidemia, kidney stones, bone fractures, and growth deficiency. Total and LDL cholesterol will often initially rise by 30% on the diet. However, lipid values stabilize after 6 months and return to normal values after several years on the KD (27,43). Kidney stones have been described historically in 6% of children placed on the KD but appear to be nearly completely prevented by empiric treatment with oral citrates (44). Decreased linear growth may occur, especially in young infants, and may be related to the level of ketosis rather than protein content of the KD (5,45). Less common side effects such as selenium and zinc deficiency, cardiomyopathy, pancreatitis, vitamin D deficiency, bone density decrease, and basal ganglia changes have also been reported. Years after the KD has been discontinued, there do not appear to be any obvious long-term adverse effects (46).

DISCONTINUATION

If ineffective, the KD can likely be discontinued within 3 to 6 months, as data suggest that benefits will occur in that time period. The optimal duration if beneficial is less clear, with several adults receiving the KD for several decades and being transitioned from pediatric KD centers (47,48). After 2 years, regardless of outcome, the risks of dietary therapy for general health and issues regarding compliance may outweigh benefits, and consideration of a gradual discontinuation should be discussed. Children with structural lesions, abnormal EEG findings, 50% to 90% seizure reduction, and those with tuberous sclerosis complex are at highest risk for worsening of seizures with diet discontinuation (49). There is no upper limit for KD duration, however, and each patient and family needs to be considered on an individual basis and involved in the decision-making process. We have found that many adults who are seizure free and driving will refuse to consider MAD discontinuation after 2 years when suggested.

Evidence indicates that once the decision has been made to wean the KD, the speed at which the diet is tapered and stopped is not relevant (50). Most children who are on the KD for long periods are weaned more slowly, in a manner similar to anticonvulsants. If ineffective, the KD can be stopped immediately without obvious ramifications (50). Our practice nowadays is to gradually reduce the ratio (or increase the daily carbohydrate limit for the MAD) every 2 weeks over a 2-month period. Abrupt discontinuations are more typically employed in monitored settings, such as a video–EEG monitoring unit.

SUMMARY

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree