Chapter 52 Dreams in Patients with Sleep Disorders

Abstract

Dreaming is defined as mental activity that occurs during sleep.1 Because dream recall and dream content have been shown to be linked to sleep physiology,2,3 the question arises as to whether the presence of a sleep disorder alters dream recall or dream content. If, for example, dream recall frequency is related to the frequency of nocturnal awakenings in healthy persons, one might expect that dream recall frequency is heightened in insomnia patients.

This chapter focuses on several sleep disorders that have been studied in relation to dreaming: insomnia, sleep apnea syndrome, narcolepsy, and the restless legs syndrome. For other diagnoses, including idiopathic hypersomnia or NREM parasomnias such as sleep walking and night terrors, systematic dream content analytic studies are lacking. See Chapters 53, 97, and 98 for a discussion of nightmares4–6 and dreams in REM sleep behavior disorder7,7a and in posttraumatic stress disorder.8,9

Dream Recall and Sleep Parameters in Healthy Persons

In order to interpret the dream recall findings of patients with sleep disorders, the arousal–retrieval model of dream recall10 and empirical evidence supporting it is briefly outlined.

The arousal–retrieval model10 hypothesizes that two steps are necessary for recalling a dream. For the first step, a certain amount of cortical arousal is necessary in order to transfer information (in this case, the dream content) from short-term into long-term memory. A period of wakefulness must follow the dream experience for the person to recall it because these storage processes do not occur during sleep. Once the dream is stored in long-term memory, the second step of the model, retrieval of the memory, takes place. Salience11 and interference12 are factors that might affect retrieval of the information. The more salient the dream experience and the less interference that occurs during retrieval, the higher the probability that the dream will be recalled. Even the repression hypothesis13 has been integrated into the model, namely, that very intense emotions may also reduce the chance of recalling the dream.

Studies in healthy persons have shown that nocturnal awakenings14,15 and low sleep quality16,17 are associated with heightened dream recall frequency, supporting the importance of the first step of the arousal–retrieval model. Findings regarding the effect of cortical activation before awakening, as measured by the electroencephalogram (EEG), on the ability to remember the dream experience are conflicting (for an overview, see reference 2). Some studies found an increase in beta activity that was related to better dream recall,18,19 but others failed to find any correlation between EEG parameters and dream recall.20,21 Because of the methodologic complexity of such studies, a conclusive statement cannot be made. Future research might use, for example, the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) arousal criteria22 to investigate whether dream recall is heightened when the person is awakened immediately following an EEG-defined microarousal.

Findings regarding the effects of salience, interference, and repression—the second step of the arousal–retrieval model—are also conflicting (for an overview, see reference 2). For example, interference reduced dream recall percentages in the sleep laboratory12 but did not seem to be of importance in explaining the variance in home dream recall.23 Whereas direct correlations between dream recall and stress measures were often not found, study participants often report that periods of stress are accompanied by increased dream recall.23,24 Repression as a trait measure was not related to dream recall in most of the studies.2 One can therefore conclude that the empirical evidence at least partially supports the arousal–retrieval model.

Waking Experience and Dreaming: The Continuity Hypothesis

Although one can find evidence for a continuity between waking experience and dreaming in Freud’s Interpretation of Dreams (for example, the term “day residue” refers to many of his associations to his own dreams that are presented throughout the book),25 the continuity hypothesis was formally introduced into dream research by Hall and Nordby.26 The basic notion is that dreams reflect waking concerns and emotional preoccupations.27 Schredl28 proposed a more-detailed model that includes several factors that can modulate the probability of specific experiences, thoughts, and feelings from waking life being incorporated into subsequent dreams. The model includes the following factors: exponential decrease of the incorporation rate of waking-life experiences into dreams with elapsed time, emotional involvement, type of waking-life experience, personality traits, and time of night.

To test the continuity hypothesis, two different approaches are typically used: experimental manipulation (e.g., showing a film before sleep) or field study (e.g., collecting dreams after a major life event such as divorce). Whereas experimental studies29 have not found strong effects of presleep stimuli on dream content, field studies clearly demonstrate relationships between waking experience and dream content.30,31 One of the factors postulated by the continuity model—that emotional intensity of a waking life experience is directly related to the incorporation rate of this event into subsequent dreams—was confirmed by a diary study.32 The empirical evidence reviewed by Schredl28 indicates that the other factors of the model also seem important even though supportive systematic research is still lacking.

Insomnia

Dream Recall

A questionnaire study of 137 insomnia patients found a relationship between the number of nocturnal wakefulness periods and dream recall.33 Whereas a small pilot study34 did not detect any differences in dream recall frequency between patients with primary insomnia and healthy controls, the first systematic study showed, as expected, that dream recall frequency was elevated in insomniacs compared to healthy controls.35 The fact that the group difference vanished when the frequency of nocturnal awakenings (questionnaire scale) was covaried in the statistical analysis supports the idea that heightened dream recall frequency is due to the frequency of nocturnal awakenings.

A laboratory study including 26 patients with primary insomnia did not find differences in the recall of visual dreams after experimental REM awakenings or NREM awakenings.36,37 However, lower dream recall after spontaneous REM awakenings was found in the patients (28%) than in the healthy controls (66%). This finding should be viewed with caution because of methodologic issues, mainly the altered sleep patterns in the patient group, including shorter REM periods before the spontaneous awakenings and inadequate gender matching (higher dream recall in women).38

To summarize, dream recall elicited in the laboratory from insomniacs via an awakening technique does not seem to differ from that of healthy controls, and the elevated home dream recall frequency for insomniacs might be explained by more frequent nocturnal awakenings. In clinical practice, insomnia patients often report that they must have slept because they remembered dreams: sleep state misperception (thinking that one is awake while the polysomnographic record indicates a sleep stage) is smallest for REM sleep.39

Nightmare Frequency and Negative Dream Emotions

Two studies40,41 reported that persons with insomnia report nightmares more often than do patients without insomnia. However, both samples were not limited to patients with primary insomnia but also included patients with other diagnoses, such as depression. Because nightmare frequency is elevated in depression,42 these findings do not permit conclusions to be drawn about nightmare frequency in patients with primary insomnia.

In another study, there were more negatively toned sleep-onset dreams in patients with insomnia, reflecting the presleep brooding or heightened cognitive arousal often present in these patients.43 However, these results were not replicated in a second study.44 More negatively toned night dreams were found in adolescents with sleep-onset problems45 and in adult insomnia patients undergoing two diagnostic polysomnographic recording nights (without forced awakenings) in the sleep laboratory.35 In addition, negative dream emotions correlated with the number of waking life problems.35 Taking into account the fact that stressors or major life events can trigger insomnia, these findings are in line with the continuity hypothesis of dreaming.28

Dream Content

Dream content analytic studies in patients with primary insomnia are scarce. A small pilot study34 including 44 diary dreams of six insomnia patients did not find any differences in dream length, dream emotions, and problems occurring in the dreams when compared with the dreams of healthy controls. The dream series of one patient, however, clearly reflected his waking-life problems:

In the presence of my boss and several coworkers, I was unable to perform a repair job. After being verbally attacked by the boss, I told him that I would like to be placed in another department. Thinking about it, I regretted saying that because I felt that the job suits me and he is the one who is not qualified for the job because of his insufficient education.34, p. 143

This pilot study34 also showed that the number of dream persons was reduced in comparison with the dreams of healthy controls, a finding that fits the continuity hypothesis because the insomnia patients in this sample scored higher on introversion (personality questionnaire) than did the controls.

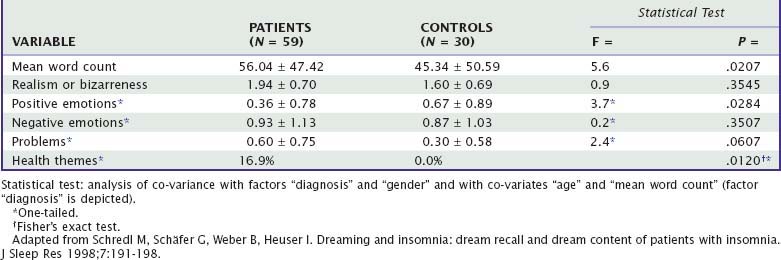

Ermann46 studied the dream content of 26 insomnia patients obtained by REM awakenings in the sleep laboratory and after spontaneous awakenings during the night. The dreams of these patients more often contained negatives in self-description, such as low self-esteem, and negatives in dream descriptions, including words like no or never or references to something being missing. Schredl and colleagues35 were able to confirm that negatives in self-description were more prominent in patients’ dreams when compared to the dreams of healthy controls. However, the other previously reported findings of negatives in the dream description and reduced number of dream persons were not replicated. Their results are based on the analysis of dream reports of 59 insomnia patients recorded after undisturbed nights in the sleep laboratory. The patients reported longer dreams, fewer positive emotions, more problems within the dream, and more aggression and health-related themes than were present in the dreams of healthy controls (Table 52-1). Moreover, the occurrence of waking-life problems was significantly related to the occurrence of problems in their dreams (r = .357, P < .005, N = 50). Similarly, if the patients reported health problems, they dreamed about health-related issues more often (r = .255, P < .05, N = 50).

Sleep Apnea Syndrome

Dream Recall Frequency

Carrasco and colleagues47 postulated two contradictory mechanisms that might affect dream recall in sleep apnea patients. First, the cognitive impairment often found in sleep apnea patients48 might impair dream recall and, second, light sleep and frequent arousals might increase dream recall (compare with the findings for insomnia patients). Questionnaire studies that applied a retrospective dream frequency scale49 with high retest reliability50 have yielded mixed results. Whereas Schredl and colleagues51 reported increased dream recall frequency in a sample of 44 sleep apnea patients, a separate study52 found lower dream recall frequency in patients (n = 309) than in healthy controls. A third study17 found no differences at all. This is in line with REM awakening studies47,53,54 that report similar recall rates for patients and for age-matched healthy controls: Schredl and coworkers found 64.2% recall for patients and 68.3% for controls,53 and Carrasco and colleagues found 51.5% recall for patients and 44.4% for controls.47 Furthermore, two studies52,55 did not find any relationship between dream recall frequency and sleep apnea parameters such as respiratory disturbance index or oxygen saturation nadir.

Nightmares and Negative Dream Emotions

In the 19th century, several researchers56–59 hypothesized that nightmares are caused by a shortage of oxygen. Using a cloth to block the mouth and nose, Boerner58 was able to induce nightmares in three different sleepers. To confirm or reject this hypothesis, the investigation of nightmare occurrence in patients with sleep apnea could be highly illuminating.

De Groen and colleagues,60 indeed, reported a relationship among snoring, breathing pauses reported by the spouse, and nightmares in a sample of Dutch World War II veterans. Fifty-six percent of the sample, however, suffered from posttraumatic stress disorder, which limits generalization of the finding. Two studies61,62 have shown significant reductions in nightmare frequency after successful treatment of a comorbid sleep apnea syndrome in posttraumatic stress disorder patients. Taking the results reported next into account, one might speculate that posttraumatic nightmares are triggered by a different mechanism than idiopathic nightmares.

Hicks and Bautista63 and Schredl64 did not find an association between snoring and nightmare frequency in a student sample. The first systematic study of nightmare frequency in sleep apnea patients52 found that on average, nightmares occurred about once per month in the patient group (n = 309), which was comparable to the mean of the healthy controls after correcting for age, sex, and overall dream recall frequency. Moreover, nightmare frequency was not related to a respiratory disturbance index or the oxygen saturation nadir. Solely the presence of a psychiatric comorbidity like depression or anxiety disorder was associated with heightened nightmare frequency,52 a finding that is in line with studies of psychiatric patients.42

The findings indicate that sleep apnea patients do not suffer from nightmares caused by oxygen desaturation. Nevertheless, it would be interesting to further the research conducted by Boerner58 by applying a full-face mask during sleep, blocking the airway for short time periods and assessing reactions to the manipulation. This paradigm would induce breathing pauses without prior adaptation processes that might occur during gradual development of sleep apnea severity over time.

Regarding negative dream emotions, Gross and Lavie54 reported that dreams were more negatively toned on nights with sleep apneas compared with nights with continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) treatment. Their sample consisted of 33 patients already treated with CPAP for at least 2 months, and they were asked to sleep 1 night without CPAP for a dream recall night. Sleeping without the beneficial treatment, however, might have stimulated worries in these patients (high indices on this night: 218 ± 138 apneas per night) and, therefore, more negatively toned dreams on the nights with apneas might simply reflect these worries rather than apneic events. On the other hand, Carrasco and colleagues47 reported a significantly increased number of violent and highly anxious dreams in 20 never-treated patients with severe sleep apnea as compared to healthy controls and speculated as to whether a hyperactivation of the limbic system might explain this finding. More negatively toned dreams were also reported by 59 sleep apnea patients rating dreams recalled in the morning after a diagnostic night in the sleep laboratory.55 Because intensity of negative emotions was not related to symptom severity (respiratory disturbance index, oxygen saturation nadir51) one might speculate whether the more negatively toned dreams are explained by the continuity hypothesis, for example, they reflect patients’ daytime problems engendered by daytime sleepiness.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree