Epidemiology of Acute Symptomatic Seizures

W. Allen Hauser

Introduction

What condition looks like epilepsy, is frequently called “epilepsy,” is frequently counted as epilepsy in epidemiologic studies, but in general has a different basis from that of epilepsy and is seldom treated as epilepsy? The answer is acute symptomatic seizures, also referred to as reactive seizures, provoked seizures, or situation-related seizures. Acute symptomatic seizures are seizures that occur at the time of a systemic insult or in close temporal association with a documented brain insult.7,8,16 This class of seizure falls into the category of situation-related seizures in the Revised Classification of Epilepsies and Epileptic syndromes suggested by the International League Against Epilepsy.7

Acute symptomatic seizures differ from epilepsy in several important aspects: First, unlike epilepsy, these seizures have a clearly identifiable proximate cause, to the extent that one can never be certain of a causal association. When one considers the temporal sequence of acute symptomatic seizures (e.g., uremia, head injury, or stroke immediately preceding a seizure), the biologic plausibility (acute disruption of brain integrity or metabolic homeostasis) and in many cases the dose effect (severity of injury correlated with the risk for seizures) all quite compellingly indicate causation. Although a risk ratio for the immediate association between cause and effect has not been calculated, it must be enormous. Second, unlike epilepsy, acute symptomatic seizures are not characterized by a tendency to recur. The risk for subsequent epilepsy may be increased in individuals experiencing such insults; in general, one does not expect seizures to recur unless the underlying condition recurs. As a corollary, such individuals usually do not need to be treated with antiseizure medication on a long-term basis, although such treatment may be warranted on a short-term basis until the acute condition is resolved.34

Few epidemiologic studies report the frequency of acute symptomatic seizures. This may be caused in part by the difficulties involved in identification. Such seizures are seldom indexed as acute symptomatic seizures; rather, the underlying condition is likely to be diagnosed and coded. This makes a study design relying on medical record review inefficient and probably leads to gross underenumeration. Individuals with acute symptomatic seizures are seldom referred to neurologists for long-term follow-up, and given the acute nature of the condition, an electroencephalographic evaluation may not be warranted or appropriate. These important sources of patient identification are thus eliminated. In studies relying on field surveys, a moderate amount of sophistication is necessary to distinguish acute symptomatic seizures from unprovoked seizures. Thus, even though causation and prognosis of acute symptomatic seizures are quite different from those of epilepsy, some recent epidemiologic studies have categorized individuals with such seizures as having “epilepsy,”31 have failed to distinguish between unprovoked and acute symptomatic seizures,28 or have not provided detailed information on cause, age, or gender.13,20,21 To study acute symptomatic seizures properly, it is more efficient to study the associated conditions, such as head injury or stroke. This procedure is not usually undertaken by most epileptologists, and seizures are not a major interest to specialists treating underlying conditions such as stroke or hyponatremia. Nonetheless, in aggregate, acute symptomatic seizures account for more than half, and in some geographic areas as much as 80%, of all newly occurring seizures. Failure to consider these conditions separately will greatly modify the apparent epidemiologic characteristics of what is called “epilepsy.” In addition to greatly increasing the apparent incidence of “epilepsy” mortality, age and gender structure of those affected is quite different if such cases were included as epilepsy, as has been suggested by some.14,18,27 At present, acute symptomatic seizures continue to be a useful concept for classification and prognosis, and the suggestions by some that the term (and presumably the concept) be abolished seems inappropriate.

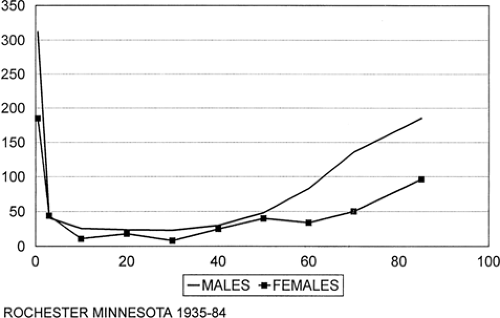

FIGURE 1. Age-specific incidence of acute symptomatic seizures (excludes childhood febrile seizures). CVD, cerebrovascular disease. |

A major difficulty with acute symptomatic seizures remains their definition. For conditions such as stroke or brain trauma, seizures occurring in the first week of an insult have generally been classified as acute symptomatic. This is clearly an artificial cut-point of convenience and would better include all seizures occurring until the point of clinical stabilization. For metabolic conditions, it is frequently unclear for systemic metabolic derangements how severe a derangement must be or for what duration it must persist. For some conditions (e.g., neurocysticercosis), the acute insult may persist for weeks or months, defying a strict temporal definition.11 This chapter reviews the incidence of acute symptomatic seizures and the incidence of seizures in conditions associated with acute symptomatic seizures. Although febrile seizures in childhood are by definition acute symptomatic seizures, they differ from other acute symptomatic seizures in their unique age specificity, high frequency in the population (up to 9%), and universality of exposure. It therefore seems appropriate that they be discussed separately.

Incidence of Acute Symptomatic Seizures

Overall Incidence

Only two studies provide detailed information regarding the incidence of acute symptomatic seizures.5,24,26 The incidence of seizures occurring at the time of systemic metabolic insults or temporally associated with an insult to the central nervous system (CNS) was determined for the residents of Rochester, Minnesota. The age-adjusted incidence rates for 1955 to 1984, the period of most complete case ascertainment, was 39 per

100,000 person-years (U.S. 1970 population). This represents about 40% of all cases of afebrile seizures identified in the community during the study period and underscores the overall importance of this class of seizure disorder in population-based incidence surveys.

100,000 person-years (U.S. 1970 population). This represents about 40% of all cases of afebrile seizures identified in the community during the study period and underscores the overall importance of this class of seizure disorder in population-based incidence surveys.

This rate is somewhat higher than that reported in Gironde, Bordeaux, France, which was 29 per 100,000 person-years. In this community-based study, acute symptomatic seizures also accounted for about 40% of all newly identified cases of afebrile seizures. The difference in absolute incidence of acute symptomatic seizures in these two communities may reflect a difference in the completeness of case ascertainment or a difference in the frequency of underlying conditions rather than any true difference in the epidemiologic characteristics. In any case, the similarities in the patterns and causes reported in the two studies are considerable.

Other studies provide some concept of frequency, but do not provide additional detail about age, etiology, or gender. In Switzerland, incidence was 25.2 per 100,000, accounting for 35% of all new cases of unprovoked seizures (Jallon). In Martinique, the incidence was 17 per 100,000, accounting for about 20% of all incident cases; in a study in children in Tunis, about 10% of all new cases were acute symptomatic. Although not specifically population based, a study from a British general practice survey33 reported 21% of newly occurring seizures to fall into the category of acute symptomatic seizures.

Gender

From what we know about the conditions associated with acute symptomatic seizures, men seem to be at higher risk than women. In both the French study and the U.S. study, the age-adjusted incidence in men was considerably higher than that in women. Sex-specific incidence in the French study, adjusted to the U.S. 1970 population, was 33 for men and 17 for women. In contrast, the adjusted incidence in the United States during a similar time interval was 56 for men and 33 for women. These differences would seem to reflect gender-related differences in incidence of underlying conditions associated with acute asymptomatic seizures rather than any specific biologic phenomena.

Age

The age-specific incidence of acute asymptomatic seizures in the U.S. study was by far the highest during the first year of life (Fig. 1). This is attributable to the high incidence of acute symptomatic seizures associated with metabolic, infectious, and encephalopathic causes during the neonatal period. Incidence declined in childhood and the early adult years and reached a nadir of 15 per 100,000 person-years among those 25 to 34 years of age. After 35 years of age, the incidence increased progressively, and reached 123 per 100,000 among those older than 75 years of age. Cerebrovascular disease accounted for about half of all acute symptomatic seizures in persons older than 65 years of age.

As mentioned previously, age-adjusted incidence is considerably higher in men than women. The sex difference was greatest at the extremes of age. Between the ages of 15 and 44, there were few differences among all causes of acute symptomatic seizures. Seizures associated with eclampsia in women of childbearing age offset a lower incidence of seizures among women associated with other causes.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree