INTRODUCTION

The most common geriatric psychiatric disorder is depression. Depression in older people has become a serious health-care issue worldwide. But it is often ignored, and thus opportunities are lost for prevention and early treatment. Blazer in his introduction to this section in the second edition of this book states, ‘Many symptom checklists have been used to estimate the burden of depressive symptoms in community populations. The results of these studies are remarkably consistent, with the range of significant depressive symptoms estimated to be 10–25%’. He quotes from 10 studies. In order to update information on prevalence and incidence of depression, we have now been able to review 38 studies of prevalence and 10 of incidence appearing in the English language during the last 10 years. Blazer continues, ‘Lower prevalences of major depression have been found in more rural samples with an estimate of less than 1% in a North Carolina rural sample, whereas urban studies have typically estimated higher prevalence. The prevalence of dysthymic disorder is generally higher than that for major depression, approximately 2–8%, depending on the instrument used in the survey’.

The problem that Blazer highlights including the diverse case-finding methods causing difficulties in drawing comparisons has substantially increased since the second edition. Most of the studies reviewed used at least one of the following instruments to diagnose depression, including those clinically based, replicating a psychiatrist’s diagnosis using ICD-10, DSM-III,-R DSM-IV criteria, CSNMD (clinically significant non-major depression) applied to the results of case-finding instruments, others to the results of psychiatrists’ clinical examination, CIDI and GMS-AGECAT (Geri-atric Mental State-Automated Geriatric Examination for Computer Assisted Taxonomy), and those based on scale cut points such as GDS-30, 15-item GDS (score >5), EURO-D scale, CES-D (Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale). Although there is some correspondence between these methods, precise comparisons are difficult to make. There is also the problem of the type of selec-tion of samples, whether or not they were purely community based, that is to say people living in their own homes or also in residential accommodation, or included hospital admissions, especially in those countries where hospitals still accommodate large proportions of patients. Are the samples randomly selected and what were the dropout rates? Was a one-stage method of identification used or a two-stage method with loss due to death, illness or refusal between stages (a particular problem in the calculation of incidence rates). Studies report their samples, grouping the data in different ways. Most do not state the kind of case they are trying to identify. The majority are likely to be interested in cases suitable for intervention but use DSM or ICD criteria aimed specifically at improving reliabil-ity between psychiatrists, and therefore likely to lead to a narrower more sharply defined concept of a case than would be acceptable to most clinicians who, as a consequence, are tempted to invent their own ‘subsyndromal’ cases for treatment. Nevertheless, in spite of these difficulties it may be possible to draw broad conclusions.

Blazer warns: ‘One of the major tasks facing psychiatric epidemiol-ogists studying depression cross-nationally in the elderly is to explain the residual depressive symptoms in community samples not easily captured by the usual diagnostic categories’ and goes on to quote the 34 studies of the prevalence of late-life depression where the preva-lence varied from 0.4% to 35%1. Arranged according to diagnostic category, major depression was relatively rare (weighted average prevalence of 1.8%), minor depression more common (weighted average prevalence of 9.8%) while all depressive syndromes deemed clinically relevant yield an average prevalence of 13.5%. Depression was more common among women and among older people living under adverse socioeconomic circumstances.

Below, we review 38 studies of the prevalence of depression and 10 of incidence across the world, published over the last 10 years, divided by continent and whether clinically-based diagnosis was used or scale cut scores.

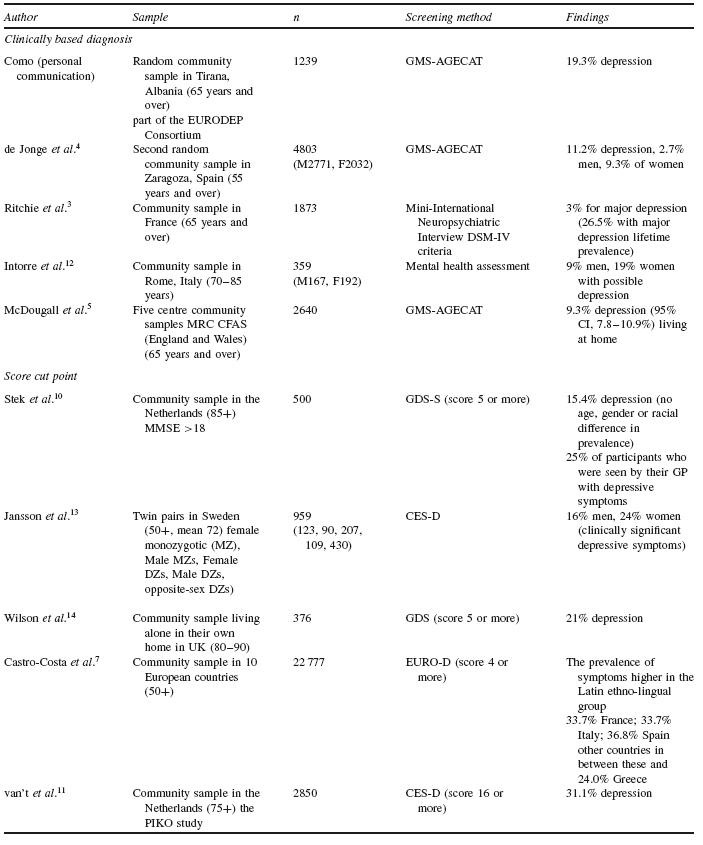

PREVALENCE OF DEPRESSION IN EUROPE (TABLE 77.1)

The EURODEP study2 (1999) reported the prevalence of depression in nine countries in Europe, which had all used the GMS-AGECAT assessment and computerized differential diagnosis. This instrument was designed to facilitate large epidemiological studies in older peo-ple where psychiatrists could not be employed for screening every case. A case was defined as one requiring some form of intervention. This package was prepared before DSM-III and ICD-10 revisions but AGECAT cases of depression have been shown in a number of stud-ies to equate with major depression, dysthymia and ‘depression not otherwise specified’.

In the EURODEP study2 all subjects were aged 65 or over, randomly selected or total samples in the community except for the Dublin centre which sampled a general practice, to yield a total of 13 803 individuals. Substantial differences in the prevalence of depression were found, with Iceland having the lowest level at 8.8%, followed by Liverpool 10.0%, Zaragoza 10.7%, Dublin 11.9%, Amsterdam 12.0%, Berlin 16.5%, London 17.3%, Verona 18.3% and Munich 23.6%. There was no constant association between prevalence and age. A meta-analysis of the pooled data on the nine European centres yielded an overall prevalence of 12.3% (95% CI, 11.8–12.9%); for women 14.1% (95% CI, 13.5–14.8%) and for men 8.6% (95% CI, 7.9–9.3%).

Using Clinically Based Diagnosis

DSM-IV criteria. Prevalence of major depression in France. Ritchie et al.3 randomly recruited 1873 non-institutionalized persons aged 65 and over from the Montpellier district electoral rolls to assess cur-rent and lifetime depression symptoms using the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview. Cases identified were re-examined by a clinical panel. Major depression was found to be 3% and lifetime prevalence 26.5%. A level consistent with many other studies.

GMS-AGECAT . Como (personal communication) reported the findings of the random community study of participants aged 65 and over in Tirana, Albania, which formed part of the EURODEP study but entered at a later date. Prevalence levels of depression were 19.3%. This is the first EURODEP study from a Muslim state in Europe. de Jonge and colleagues found levels of depression in the second Zaragosa study of persons aged 55 and over of 11.2%4. McDougall et al.5 reported the prevalence of depression in the Medical Research Council Cognitive Function and Ageing Study (MRC-CFAS), and the prevalence of depression and depressive symptoms in those living in institutions6. The MRC-CFAS is a population-based cohort comprising 13 004 individuals aged 65 and above from five sites across England and Wales. A stratified random sub-sample of 2640 participants were interviewed by GMS-AGECAT, showing that the prevalence of depression in those living at home was 9.3% (similar to the 9.2% in an earlier Liverpool study (n =5222)2 and for those living in institutions was 27.1%. The prevalence increased if subjects with concurrent dementia were included. This is of interest because such cases of dementia are often excluded in surveys of depression but may require treatment for depression. Also, such exclusion may give a spurious impression of a fall in the proportion of people with depression with increasing age as the prevalence of dementia escalates. Depression was more common in women (10.4%) than men (6.5%) and was associated with functional disability, co-morbid medical disorder and social deprivation.

Using Scale Scores

EURO-D based prevalence in 10 European countries.Castro-Costa et al.7 administered the EURO-D with score ?4 to cross-sectional nationally representative samples of non-institutionalized per-sons aged 50 years and over (n =22 777) across 10 European countries – Denmark, Sweden, the Netherlands, Germany, Austria, Switzerland, France, Spain, Italy and Greece – as part of the SHARE study. The distribution of gender and age did not differ between countries. Educational levels were lowest in the Latin countries (France, Italy and Spain) and in Greece. The highest country-specific depression prevalence rates were found in France (33.7%), Italy (33.7%) and Spain (36.8%), with a 9% difference between the lowest of these (33% in France) and the next lowest (24% in Greece). Prevalence in the remaining countries was 18–19%. Heterogeneity between countries was statistically significant (p 0.001). The pattern and extent of between-country differences were not affected by direct standardization for gender, age, education, verbal fluency or memory. But the SHARE data are limited by the relatively low proportion of households and individuals responding. This may, unfortunately, represent a secular trend in more developed countries. The net effect may be an underestimation of the true prevalence of depression8,9.

The EURO-D scale was developed in order to include more cen-tres in the EURODEP study. It was shown to have strong conceptual validity and high internal consistency when applied to data from 21 724 subjects. EURO-D scores tended to increase with increasing age, unlike the levels of prevalence of depression. Women had gen-erally higher scores than men, and widowed and separated subjects were higher than those who were currently or never married.

GDS in the Netherlands.Stek et al.10 assessed the prevalence of depression and correlates from a representative sample of 599 community-based 85-year-old subjects with a MMSE >18. The prevalence of depression, as measured with a GDS-S score of 5 points or more, was 15.4%, not very different from the EURODEP level for Amsterdam of 12.0%.

CES-D in the Netherlands.Van’t et al.11 assessed the prevalence of depressive symptomatology and risk indicators in 2850 partici-pants aged 75 years or more in the PIKO study. The prevalence of depressive symptoms was 31.1% across all participants.

PREVALENCE IN THE AMERICAS (TABLE 77.2)

Using Clinically Based Diagnosis

DSM-IV . One study15 in the United States examined the current and lifetime prevalence of depressive disorders in 4559 non-demented individuals aged 65 to 100 years. This sample represented 90% of the elderly population of Cache County, Utah. The researchers employed DSM-IV criteria for major depression, dysthymia and sub-clinical depressive disorders using a modified version of the Diag-nostic Interview Schedule. The point prevalence of major depression was 4.4% in women and 2.7% in men (p =0.003), similar to the level (3%) found by Ritchie et al.3 in France using similar criteria. Other depressive syndromes were surprisingly uncommon (combined point prevalence, 1.6%), and the current prevalence of major depres-sion did not change appreciably with age. They also estimated that lifetime prevalence of major depression was 20.4% in women and 9.6% in men (p 0.001) (Ritchie 26.5%), decreasing with age.

In Quebec, Preville et al.16 used the ‘Enquete sur la sante des aines’ study, conducted in 2005–6, to obtain a representative sam-ple (n =2798) of community-dwelling older adults. Of this sample, 12.7% met the criteria for depression, mania, anxiety disorders or benzodiazepine dependency. The 12-month prevalence rate of major depression was 1.1% (again demonstrating the low levels found with these criteria) and the prevalence of minor depression was 5.7%.

ICD-10, SCAN . Two studies were conducted in Brazil, and one study in Peru, Mexico and Venezuela. Costa et al.17 investigated the prevalence and correlates of common mental disorders with semi-structured interviews administered by a psychiatrist. During the study, a two-phase population survey of 392 persons aged 75 years and over were screened for depression and mental disorders using the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12) and Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS). In the second phase, 20% were evaluated using the SCAN to generate ICD-10 diagnoses. The prevalence of depressive episode was 19.2% with no effect of gender or age. Lay-administered interviews were thought to underestimate the prevalence of mental disorders in older people and they recom-mended one-month prevalence as more appropriate for the oldest-old given patchy recall of distant experiences.

DSM-IV .Xavier et al.18 described the prevalence of minor depres-sion as 12% of the oldest-old in a random representative sample (n =77 subjects) aged 80 years and over from the Brazilian rural southern region using DSM-IV criteria. A small but interesting study which was found to be consistent with others quoted here concerning younger age groups.

DSM-IV and ICD-10 GMS-AGECAT . Investigating the prevalence in five locations in Latin America, Guerra et al.19

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree