14 Epilepsy

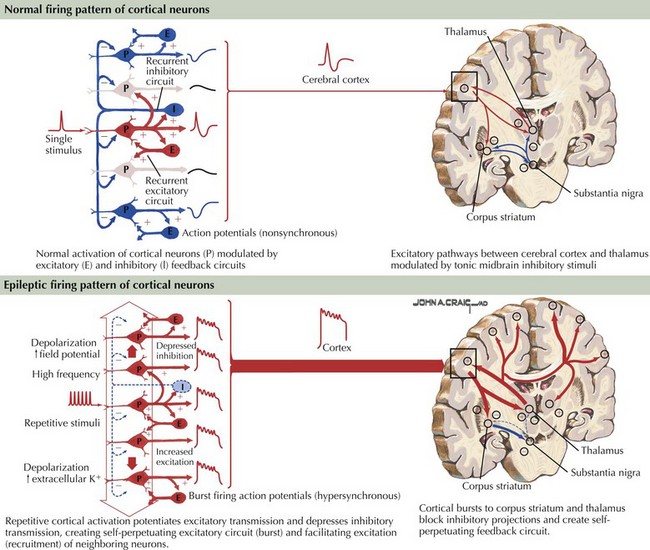

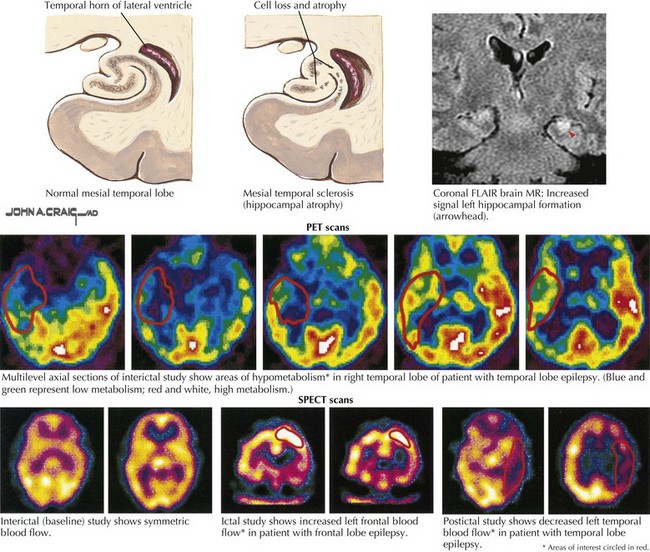

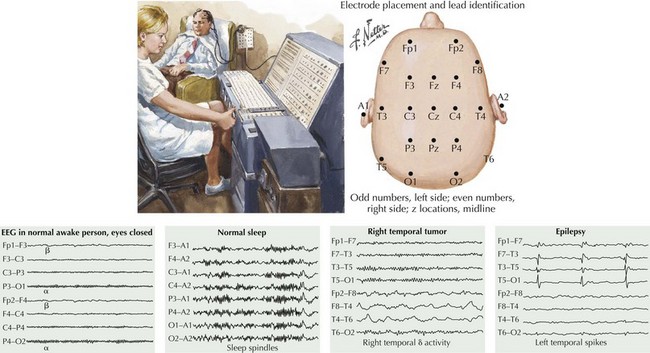

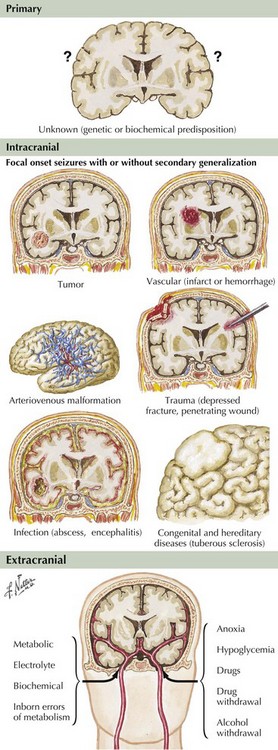

Epilepsy is generally defined as an illness of recurrent seizures. The prevalence of epilepsy is estimated at 1 in 200 persons. It affects all ages and is generally a chronic problem with significant personal, social, and economic impact, often affecting the ability to hold jobs and drive. Poor epilepsy control and the seizures themselves can lead to significant cognitive and personality changes as well as chronic depression. The incidence is about 200,000 new cases yearly in the United States. The clinical manifestations are initiated by abnormal electrical discharges within the brain. The underlying pathophysiology is complex and not completely defined, but ultimately involves repetitive cortical potentials leading to altered modulation of excitatory inputs and suppression of inhibitory feedback circuits (Fig. 14-1). The diagnosis of epilepsy is primarily clinical, based on patient and witness history of the events and on the neurologic examination. An abnormal electroencephalograph (EEG) may substantiate a suspected diagnosis with specific EEG patterns, particularly focal or generalized spikes or spike-and-wave discharges, being highly associated with seizures. Many other EEG changes are not specific for seizures and are of little help in differentiating epileptic from nonepileptic events. Epilepsy is a treatable disease, often with a specific correctable medical or surgical pathology. Accurate diagnosis must be the predominant goal in approaching a patient with seizures of recent onset. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and neuroimaging studies are critical to define any potentially treatable structural brain disease (Fig. 14-2). Laboratory testing may assist in the evaluation and treatment. Patients with chronic forms of epilepsy require long-term medical treatment. Failure of medical therapy or quality-of-life issues may necessitate intensive patient evaluation for potential seizure surgery. Surgical removal of carefully selected areas of diseased brain may provide improvement and often a cure.

Partial Seizures

Simple Partial Seizures

Clinical Vignette

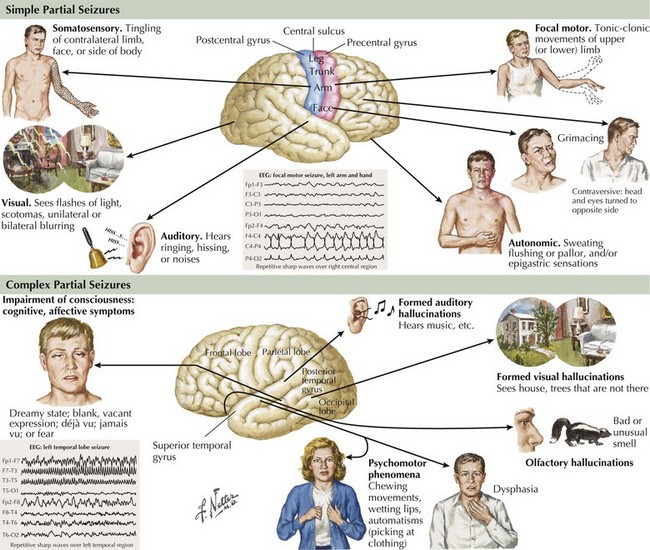

This history represents typical simple partial seizure (SPS). During the episodes, patients are conscious, aware of their surroundings, and able to respond appropriately. Partial seizures originate and develop within a discrete area of the cerebral cortex (Fig. 14-3). They may have a “Jacksonian march” wherein the cortical epileptic discharges spread along contiguous cortical regions. The brain area involved determines the clinical signature of the event. Symptoms may be somatosensory, as in the above vignette, when the origin is in the parietal lobe, motor when discharges arise from the frontal or motor cortex, and visual when they begin in the occipital lobe. However, the relation of focal cortical location to clinical expression is not absolute. Seizures may start in a “silent” cerebral cortical area with the manifest ictal symptoms representing the result of the discharge spreading to neighboring cortical areas. SPSs may occasionally have autonomic, psychic, or cognitive manifestations. Other seizure types may start off as SPS and then evolve into broader disruptions. By definition, these simple ictal events do not include any change in level of consciousness and it is this preserved responsiveness to the external environment that characterizes SPSs. Auras, a warning that a patient experiences prior to altered or loss of consciousness, are, in effect, SPS.

The clinical evaluation of patients with partial epilepsy must include an EEG, a neuroimaging test, and laboratory testing. Although routine EEG recordings may often be normal in patients with unequivocal seizure disorders, it remains of paramount importance for the correct diagnosis and classification of the ictal events. Even when the neurologist suspects a seizure disorder from the clinical description, the EEG, if positive, may serve as an important confirmatory test when the episode is not well described. It should be remembered, however, that a routine EEG represents only a limited time sample and that sporadically firing interictal discharges can, therefore, be easily missed in patients with unequivocal seizure disorders. Long-term seizure telemetry units and ambulatory EEG monitoring are now available to increase recording time and enhance detection rates. The EEG hallmark of partial epilepsy is focal spikes or spike-and-wave discharges. Because delta-wave non-REM sleep activates or disinhibits epileptiform discharges, the EEG is preferably recorded during both wakefulness and sleep to increase the probability of making the correct diagnosis and defining the focal origin (Fig. 14-4). A definitive result is often obtained only during sleep recordings. Repeated recordings may be necessary if the nature of the episode is unclear or if psychogenic nonepileptic seizures are suspected. In contrast, the EEG in patients with epilepsia partialis continua contains spike-wave discharges in a variably continuous manner, often in the contralateral frontal lobe. A small number of individuals in the healthy population have abnormal EEG containing focal spikes but do not go on to have seizures later in life. This emphasizes that an abnormal EEG can only be interpreted in light of the presenting clinical symptoms and that it does not, on its own, define a seizure syndrome or dictate treatment. At best, the EEG may capture an ongoing seizure and greatly clarify its origin. It may also help to localize the epileptogenic pathology, guiding surgery if medical treatment fails.

Neuroimaging studies, especially MRI, are vital to the evaluation of new-onset or changing-pattern seizures. Brain computed tomography is a useful screening technique when MRI is not available. The onset of new partial seizures strongly suggests the development of a new pathologic process, including tumors (primary or metastatic) or abscess in the adult population, stroke from emboli or rarely vasculitis in older age groups, and focal encephalitis such as Rasmussen encephalitis in children, herpes simplex encephalitis in children or adults, or head trauma (Fig. 14-5). However, sometimes a patient with a lesion, for example, mesial temporal sclerosis or an AVM, does not present with partial seizures until adulthood. Rarely, acute-onset partial seizures may be caused by metabolic abnormalities, such as nonketotic hyperglycemia or hypoglycemia.

Complex Partial Seizures

Clinical Vignette

This patient’s history represents a typical example of complex partial seizures (CPSs). The clinical manifestations of this seizure type include changes in alertness or level of consciousness, partial amnesia, and automatisms (Fig. 14-3). Patients often perform simple motor tasks and even may walk during the seizure. CPSs usually arise from mesial temporal structures but can also originate in other extralimbic temporal structures or the inferior frontal lobe and spread via the uncinate fasciculus and other pathways to the mesial temporal area.

Because complex seizures are of focal origin, patient evaluation is similar to that undertaken for SPS. Typically, the interictal EEG (i.e., obtained between seizures) reveals spike discharges in one or both anterior temporal lobes. The ictal EEG is usually abnormal, with recurrent focal spikes or rhythmic activity. Brain MRI with special attention given to the temporal lobes shows that these patients often have mesial temporal lobe sclerosis with cell loss and atrophy (see Fig. 14-5).

Generalized Seizures

Tonic–Clonic (Grand Mal) Seizures

Clinical Vignette

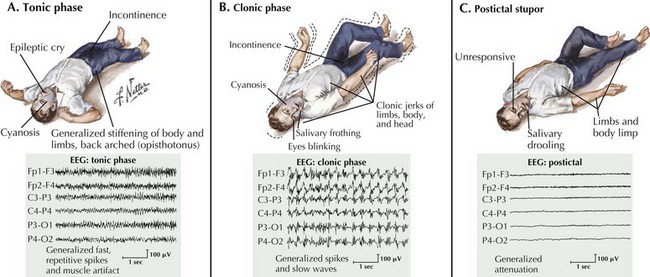

Grand mal seizures start with loss of consciousness, a cry, generalized tonic muscle contraction, and a fall (Fig. 14-6). Autonomic signs are often present during the tonic phase, including tachycardia, hypertension, cyanosis, salivation, sweating, and incontinence. The tonic muscle contraction becomes interrupted relatively soon and is followed by the clonic phase of the seizure with brief relaxation periods progressively lengthening until the seizure eventually abates. Patients may remain stuporous for a moment and eventually awaken confused with postictal headaches, lethargy, disorientation, and myalgia that may persist for up to a few days.

Absence (Petit Mal) Seizures

Clinical Vignette

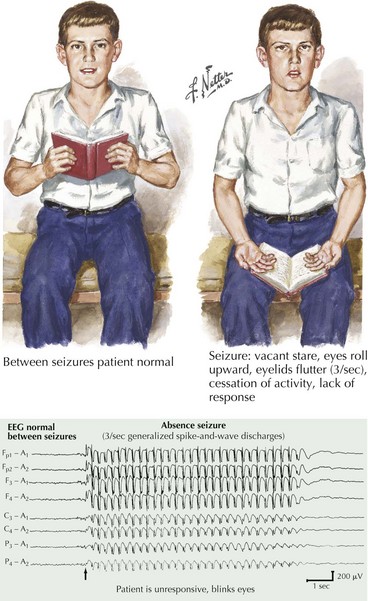

This is the typical history of a child with generalized absence (petit mal) seizures. Petit mal epilepsy is the classic example of benign primary generalized epilepsy, which tends to remit in adulthood. Brief lapses in consciousness without an aura or any postictal symptoms are the main features (Fig. 14-7). Automatic movements may be observed but are generally simple and brief. The neurologic examination is usually normal.