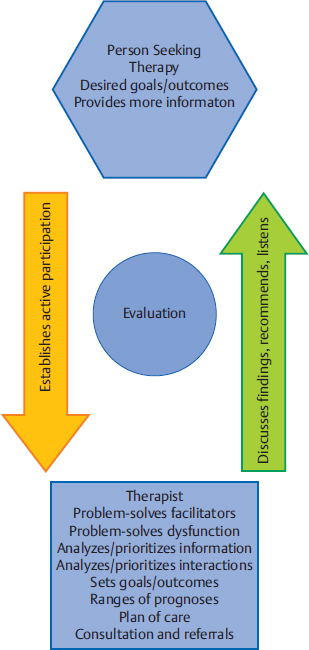

8 Evaluation and Developing the Plan of Care This chapter develops and explains the evaluation process of the Neuro-Developmental Treatment (NDT) Practice Model. Its purpose is to make cognitive processes of clinical reasoning explicit. Evaluation involves determining why clients do what they do. On a detailed and interactive level, clinicians using NDT constantly seek to understand the relationships among participation in individual contexts, activity, and body structure and function; prioritize these factors in their analyses of their clients’ abilities and disabilities; and use this problem-solving process to set prognoses, measurable functional outcomes, and the plan of care. The last sections provide information and guidelines for mentoring students and novice clinicians in evaluation processes, and the details of two outcome writing and measurement systems. Learning Objectives Upon completing this chapter the reader beginning to learn about NDT will be able to do the following: • List the sequence of evaluation processes in the NDT Practice Model. • Write a profession-specific, measurable functional outcome for a client from his or her practice, and identify whether the outcome is an activity or a participation outcome. • Identify at least two body system integrities and two body system impairments that influence the outcomes listed above. • List the components of the plan of care important to the NDT Practice Model and describe briefly why each is important. Upon completing this chapter the reader who is more experienced with NDT will be able to do the following: • Use the evaluation process in the NDT Practice Model to document evaluation of clients from his or her practice. • Write functional outcomes, quickly determining how changing contexts (personal and environmental) can lead to additional outcomes and greater activity/participation for clients from his or her practice. • Describe the interaction of body systems typically evaluated by the profession of the reader, emphasizing how one system may alter, intensify, or create new integrities or impairments in another body system. • Describe the interactions of body systems, activities, and participation in terms of their mutual influences on a client from his or her practice. • Write an individualized plan of care for clients from his or her practice, including all components listed in this chapter. Upon completing this chapter the advanced reader who is experienced with NDT will be able to do the following: • Write evaluations and plans of care for clients in concise descriptions that can also be used to teach the process to novice clinicians. • Explain to novice clinicians, team members, clients and family members, and peers the structure and purpose of the NDT Practice Model evaluation and plan of care content in terms applicable to each person’s role in the therapeutic process. • Develop problem-solving templates to explain the relationships among participation/participation restrictions, activity/activity limitations, and body system integrities/impairments to instruct him- or herself and others in the possibilities of these interactions as they relate to client outcomes. The evaluation portion of practice (Fig. 8.1) asks the question, Why? Why can clients do what they can do, why can’t they do what they can’t do, and what can the clinician do about it? Evaluation is a complex process dependent on the clinician’s knowledge base of pathophysiology, domains of functioning, typical and atypical development throughout the life span, and the lifelong influences on functioning of effective, ineffective, and compensatory postures and movements. Evaluation requires profession-specific abilities to synthesize and analyze examination findings. The process requires cognitive problem-solving skills using analytic (hypothesis-guided inquiry or hypothetico-deductive reasoning) and nonanalytic strategies (forward reasoning or pattern recognition), and understanding the situation from the client’s perspective, life story, and context (narrative reasoning).1,2,3,4,5,6,7 Fig. 8.1 Evaluation is the problem-solving and hypothesizing portion of the Neuro-Developmental Treatment Practice Model. Evaluation is a process of assigning meaning to all of the information gathered through client/family interviews and discussions, observation of all domains of human functioning (participation, activity, body structure and function), handling for examination, and standardized and nonstandardized testing of all domains of human functioning. Clinicians evaluate this information in accordance with their professional practice acts. Clinicians also seek information from theoretical sources, such as theories of motor control, motor learning, motor development, neuroplasticity, human behavior, and related areas of inquiry to evaluate their findings. See Unit III for detailed information on motor control, motor learning, motor development, and neuroplasticity theories. In clinical practice, therapists must decide how to synthesize and analyze information from these many fields of inquiry, interpreting theoretical possibilities and research findings to form the rationale for intervention strategies. On a deeper level, the why questions lead the clinician to hypothesize about or recognize relationships: Do each of the impairments directly cause activity limitations and participation restrictions, or do combinations of impairments and context have a greater impact and correlation to activity and participation than any one system would have by itself? Are there impairments or combinations of impairments that affect activity and participation more than others do? Are there impairments that influence other impairments, increasing their severity or preventing improvement in structure or function? For example, in excessive and sustained coactivity of muscles around a joint, joint mobility through its full range is prevented, and muscular strength and endurance cannot fully develop, resulting in secondary impairments of joint soft tissue restrictions, muscle stiffness and morphology changes, weakness, and decreased muscle endurance. This in turn may increase co-activity force and endurance in very small joint ranges in voluntary attempts to control a limb position or to move, further preventing mobility and strength development and resulting in permanent morphology changes within the muscles. Describing how clinicians use Neuro-Developmental Treatment (NDT) to analyze and synthesize information is a daunting task. However, it is necessary to describe and explain the problem solving that NDT clinicians use to create a deeper understanding of NDT practice. Evaluation requires a model to structure its tenets—a reference for hypothesis generation and pattern recognition. A set of beliefs about organizing and interpreting information is inherent in evaluation for any clinician practicing with any clinical approach, whether the clinician is able to express these beliefs explicitly or not. In NDT, the NDT assumptions and philosophy describe the beliefs that NDT holds. The NDT Practice Model provides the structure for these beliefs and assumptions upon which evaluation depends. Because of this organizing and interpretive structure, the way an NDT clinician interprets and applies all information to intervention is distinct from other approaches. Given that evaluation assigns meaning to all information gathered and measured, there needs to be a process whereby the clinician recognizes, groups, and prioritizes the information to determine whether intervention is warranted. How do clinicians perform this process in the professions of occupational therapy, physical therapy, and speech-language pathology? A search for literature that explains the evaluation process reveals a great paucity of information, with only a few studies addressing the subject.2,3,8 These few studies of clinical decision making or clinical reasoning outline an evaluative process that includes prioritizing problems, deciding which problems are the largest barrier to function, and which problems may be most amenable to intervention. How this process works requires qualitative research methods. The most detailed literature concerning the evaluation process focuses on the difference between novice and expert practitioners, describing their problem-solving processes. Qualitative research methods based on structured and repeated interview analysis and coding are used to understand the cognitive processes that clinicians use during clinical reasoning.4,5,9,10,11,12,13 Further information about this process is found in the section on Mentoring Students’ and Novice Clinicians’ Problem-Solving Activities. It is the basis for sample teaching strategies for students and novices. Gaining expertise in evaluation and intervention appears to be a developmental process for the clinician.10 Although gaining effective evaluation and intervention skills is unquestionably a highly complex phenomenon, this chapter identifies salient characteristics of the process. How can a clinician organize, analyze, and prioritize the vast amount of clinical information using the NDT Practice Model? Let’s begin with a general pathway through the evaluation process that can assist clinicians in problem solving, synthesizing, and analyzing information in preparation for intervention. Evaluation Summary and Prioritization of Participation/Participation Throughout the evaluation process, the clinician must realize that no two clinicians will make the exact same lists and priorities, even if they are of the same profession. Each clinician’s own contextual factors, educational background, and experiences influence the evaluation. In addition, as the clinician becomes more familiar with the client, the lists of participation, activity, and impairments are refined. As the client changes, these lists also change. Finally, it is likely that clinicians in the different professions (occupational therapy, physical therapy, speech-language pathology) will make different lists and priorities. After the information gathering and examination, the clinician lists and prioritizes information in each domain and context in order of importance for the client and family. • The client’s participation/participation restrictions within the client’s personal, family, and community facilitators and barriers. • The client’s activities/limitations within the client’s personal, family, and community facilitators and barriers. This individualized list is the rationale for detailed information gathering and examination. No two prioritized lists will ever be the same; each client will have a unique list. The therapist using NDT considers this list to be the foundation for further analysis, outcome setting, and intervention planning. Next, the clinician hypothesizes which body system integrities and impairments influence participation/restrictions and activity/limitations. The list is prioritized based on hypotheses of influence each system has on participation and activity. Therefore, listing and prioritizing single- and multisystem integrities and impairments are highly individualized. For example, let’s assume that one client’s participation restriction is that she cannot unload her dishwasher at home. We will assume the same restriction for a second client for comparison purposes. The two clients, however, have different integrities and impairments that are hypothesized to cause the restriction. Table 8.1 provides a comparison. Furthermore, the context of unloading the dishwasher will influence intervention. Perhaps for the first client, unloading the dishwasher has been a daily skill used for many years, and it is important to that client to regain the skill. Perhaps for the second client, the skill is easily taken over by her husband, who frequently performed this task anyway. It may not be so important for the second client to set unloading the dishwasher as an outcome for intervention, and she may choose another outcome that is more important to her. Participation and activity outcomes for intervention are set collaboratively between the therapist and the client and family. The client and family often know what they want as outcomes: “I want to walk again,” “I just want her to call me ‘Mom’,” “I want to go back to work,” “I want him to eat at the table with us.” These outcomes are always respected by the NDT clinician, even if the clinician thinks that the outcomes may not be attainable. Clinicians are well aware that setting outcomes with their clients requires compassion, humility, and the ability to express possibilities as knowledgably as possible. Talking with the client and family about what can be accomplished today, this week, this month, and adjusting outcomes, based on the knowledge that the individuals involved gain with time and work as they build a therapeutic relationship, is required. This approach helps both client and clinician to strive for attainable outcomes over time. Table 8.1 Comparison of two clients with the same desired participation outcome

8.1 Evaluation Using the Neuro-Developmental Treatment Practice Model

8.1.1 Evaluation Requires a Framework

8.1.2 What Do We Already Know about How Clinicians Evaluate and Treat?

8.1.3 A System for Evaluation Using the NDT Practice Model: The Problem-Solving Process

Restrictions and

Activities/Activities Limitations with Contextual Factors

↓

Summary and Prioritization of Body System Integrities and Impairments with Contextual Factors as They Affect Participation and Activity

↓

Set Participation and Activity Outcomes

↓

Analysis

(Clinical hypotheses of relationships among all domains)

↓

Analysis

(Potential for change and prognosis based on optimal participation, activity, body structure/function, and contextual resources decreasing function in participation, activity, body structure/function, and lack of contextual resources)

Listing and Prioritizing Information

Setting Outcomes with the Client and Family

Client One | Client Two |

Integrities (prioritized) | Integrities (prioritized) |

• Intact cognition | • Adequate strength in shoulder complex for overhead reach |

• Intact motor planning | |

• Adequate passive range of motion in UEs | • Ability to use trunk control in all three planes of motion with UEs supported on countertop |

• Initiates shoulder motions below 90° | |

Impairments (prioritized) | Impairments (prioritized) |

• Lacks UE movement against gravity above 90° shoulder flexion | • Poor awareness of body position in space; visual attention to body part improves awareness |

• Lacks thoracolumbar extension mobility to assist overhead reach | • Unreliable gradation of muscle force production—uses either too much or too little grip force (visual attention to task helps), therefore grasp of items in dishwasher is unreliable |

• Delayed initiation and limited ability to sustain postural extension in LEs, notably hip extension and isometric ankle extension in weight bearing | • Unpredictable timing of muscle activity of LE postural extensors for reliable postural stability during reach down and diagonally to dishwasher, followed by the overhead reach |

• Lacks control of eccentric LE extension when reaching down into bottom dishwasher rack | • Delayed eccentric extension in LEs when reaching down to dishwasher |

• Motor planning impairments suspected |

Abbreviations: LE, lower extremity; UE, upper extremity.

Note: We can see that, although the task is the same one, the two clients differ vastly in the integrities and impairments that are hypothesized to contribute to the restriction. Therefore, the intervention for each of these clients requires different strategies. The integrities and impairments will also influence participation outcome setting by the client and clinician and will influence the length of time predicted to achieve the selected outcome.

Writing Outcomes

Outcomes are the anticipated participation and activities (functions) that are expected under stated contexts. They include the following information:

1. The name of the client. Occasionally the name of the family appears in an outcome.

a. Mrs. Jones.

b. Claire’s mother.

2. An action verb that is observable.

a. Mrs. Jones will stand.

b. Claire’s mother will feed.

3. The functional performance itself.

a. Mrs. Jones will stand up from her bed.

b. Claire’s mother will feed Claire.

4. The contexts (conditions and criteria) of the function.

a. Mrs. Jones will stand up from her bed every morning next week after placing her feet on the floor while her husband supports the left side of her trunk and shoulder.

b. Claire’s mother will feed Claire pureed fruits from an adaptive spoon (may state brand or type) at lunch tomorrow, completing the entire meal within 20 minutes while Claire sits in her adapted high chair with all straps secured.

Note that the functional participation or activity is stated immediately after the verb. With our clients who change slowly or who are anticipated to achieve a limited number of functions, the supporting contexts (conditions and criteria) are stated in a detailed way so that changes in these details can denote progress.

Take care to separate the function from the conditions under which that function will occur. For example, an outcome may be written “Johnny will sit…” Sitting may be the function the clinician targets or it may be the condition under which Johnny will do something else. “Johnny will eat his dinner while sitting in his booster chair” or “Johnny will write his name on his English paper when sitting at his desk in his wheelchair” may better reflect that sitting is a condition of the function and not the function itself if the clinician is measuring eating or writing as an activity rather than achieving sitting activities.

Contexts (conditions and criteria) describe where, when, for how long, and how well the client performs a particular activity. Johnny may sit in his wheelchair in his classroom to complete his spelling test for 15 minutes with his left hand holding the paper down while using a dynamic tripod grasp on his pencil.

The NDT clinician plans outcomes for each client that reflect more skillful function over time. However, is the progression from session outcome to long-term outcome simply a manipulation of performing a functional skill longer or faster, with more strength or better range of motion? Or does the function itself change over time? Any of these measures may change to reflect progress, and the clinician thinks carefully about what will change and how it will change to influence functional performance as the client moves through each intervention session. A clinician may change the following:

• The participation or activity function itself.

• The conditions and criteria under which the function will be performed. These conditions and criteria include the following:

The various environments the client will function in.

The various environments the client will function in.

The range of personal contextual factors, such as personality and family structure and function.

The range of personal contextual factors, such as personality and family structure and function.

The people the client will interact with while functioning.

The people the client will interact with while functioning.

Criteria such as the time of day the function will be performed, the time required to complete the function, how far or how long the function is performed.

Criteria such as the time of day the function will be performed, the time required to complete the function, how far or how long the function is performed.

The posture and movement used to perform the function.

The posture and movement used to perform the function.

For example, a client who is recovering from a stroke or traumatic brain injury (TBI) or a child with cerebral palsy (CP) after a hip surgery may quickly recover the skill of sitting up again and move on to more challenging activities in standing and walking, or progress from no speech and gesturing to using single words and multiple gestures. The clinicians treating these clients may predict that participation and activity domain functions will progress quickly based on the pathology, medical history of the client, and predictable patterns of recovery. Therefore, outcomes reflect performance changes in several functional skills.

Conversely, a 10-year-old child with CP with Gross Motor Function Classification System (GMFCS),14 Manual Ability Classification System (MACS),15 and Communication Function Classification System (CFCS)16 Level V functioning may achieve a few participation and activity functions only over many years’ time. With this child, sensitive measures of the environmental conditions and performance criteria are critical to show progress and, in fact, may show changes in participation because the conditions and criteria change. For example, for those caring for this child, there is a clear advantage to the child’s ability to eat orally safely when fed by his parents, aides at school, a respite care worker, and an aunt versus only being able to eat when his mother feeds him. The activity remains the same for this child—that of eating when fed by an adult—but his skill in eating safely when fed by less trained and less familiar adults allows him to be cared for at home and at school, and when his parents are out of town. His participation has broadened as a result.

Outcomes may be categorized by length of time to complete. In the initial documentation, clinicians often designate short- and long-term outcomes, but the lengths of time vary for each clinician according to workplace setting. Therefore, it is wise to record a time length for these outcomes. For example, a school-based therapist might write 9-month (long-term outcomes) on the individualized education plan (IEP), with the short-term outcomes designated as 3-month outcomes. In contrast, a therapist working at an inpatient rehabilitation facility with adults may view long-term outcomes as those measured after a 3- to 4-week period, whereas a short-term outcome in an acute setting is set to be measured in 3 to 5 days. As we will see in the next chapter, the therapist also sets a session outcome that is functional.

Progression from session to short-term to long-term outcome does not necessarily have to be a graduated change in criteria and conditions. For example, a long-term outcome may be that a client is able to ascend six steps without a handrail on the outside of his home, and a short-term outcome may be to step up a curb to a sidewalk. A long-term outcome may be that a child dresses himself in the morning for school, whereas a short-term outcome is that he dresses himself on Saturday mornings (when there is more time to complete the task). A long-term outcome may be that a teenager feeds himself lunch in the cafeteria at school, whereas a shorter-term outcome is that he feeds himself a sandwich in the classroom with only adults present. Each of these outcomes is itself a participatory outcome, yet the shorter-term outcomes have fewer postural, movement, and contextual demands.

The NDT clinician is often likely to set outcomes established and valued by the client or family rather than those taken from standardized and nonstandardized test items. These tests have the limitation of offering only selected functions (or postures and movements that are said to be functions) to measure and are often not compatible with the highly individualized care provided by the clinician using the NDT Practice Model.

Finally, the clinician using NDT considers lifetime outcomes. Because stroke, TBI, CP, and related neurodisabilities affect people for their lifetime, the clinician is concerned with the effects of participation restrictions, activity limitations, and body system impairments that are likely to change through the years. The clinician considers possible consequences of the relationships among these domains and the possible effects of practicing ineffective postures and movements on the future in terms of years and decades. These variables expand the knowledge that the clinician seeks—that of life span understanding of skill development and decline, variability in people with and without pathology, and the consequences of functioning with ineffective and compensatory posture and movement.

For further information about outcome writing and measuring, see section on Writing Outcomes for Clinical Practice and Statistical Analysis.

Analyzing Relationships among Domains of Functioning

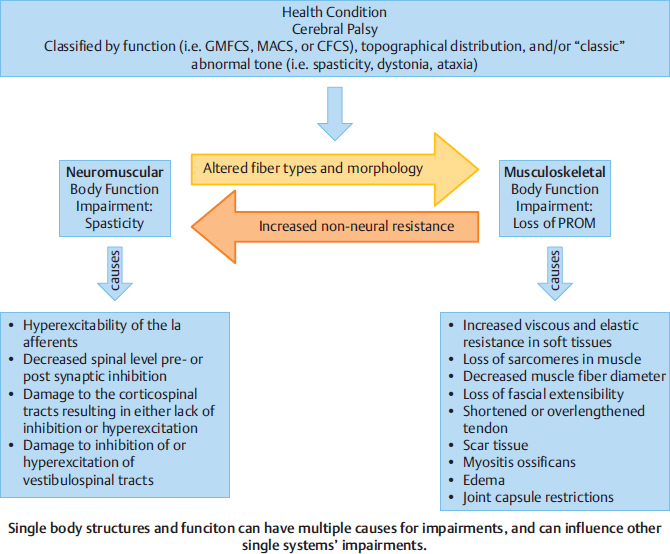

The clinician analyzes the relationship of all domains of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF), looking at a big picture of how each item of a domain influences aspects of the same domain and other domains. An example in Fig. 8.2 from the body structure and function domain shows the complexity of influences of body systems on each other over time.

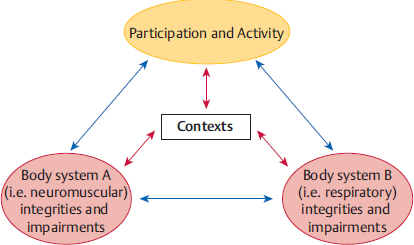

The clinician analyzes how participation and activity affect body systems and how single- and multisystem integrities and impairments influence participation/restrictions and activity/limitations. These relationships are not linear, however, and the problem-solving possibilities are complex. Body system integrities can support participation and activity, as well as support function in other systems. Participation and activity can support body system integrities. Impairments can cause participation restrictions and activity limitations, but the restrictions and limitations can also cause further impairments or new impairments. Impairments in one body system can cause impairments in another, and these influences could potentially continue. The NDT clinician considers all of these current and potential future relationships (Fig. 8.3).

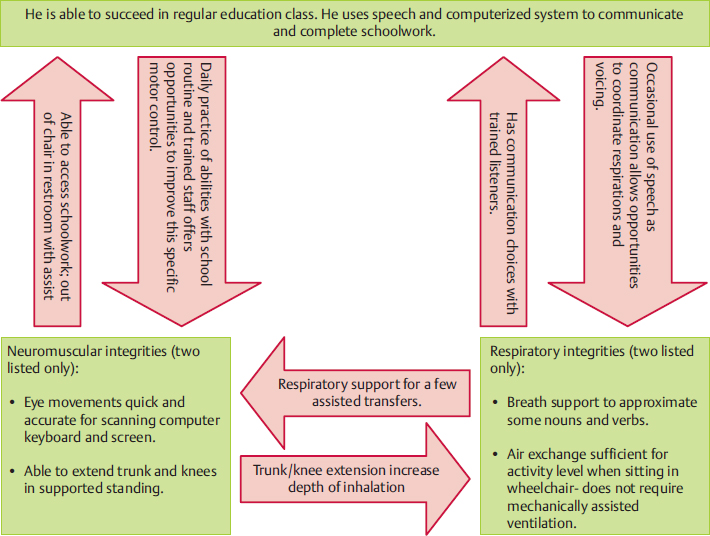

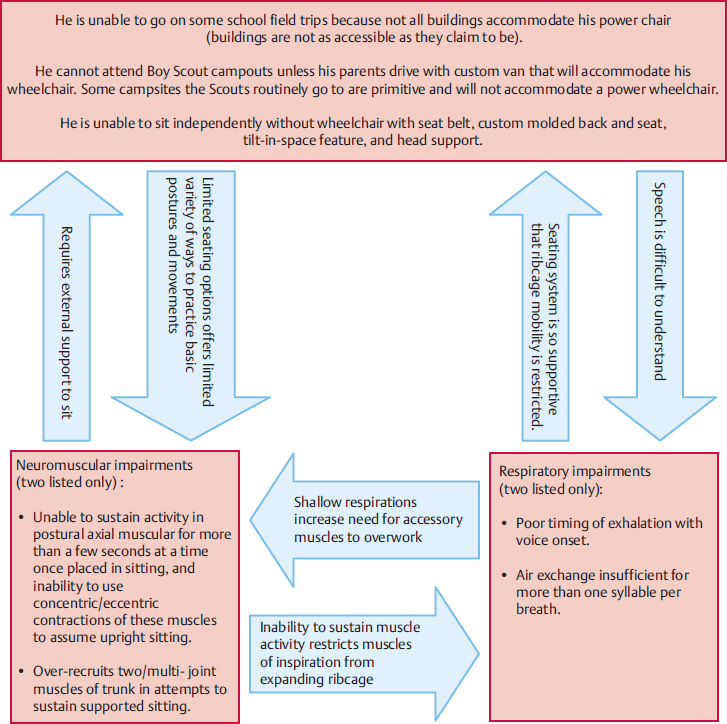

Fig. 8.4 and Fig. 8.5 show examples of positive ICF domain function and negative domain function in a teenager with CP.

A Look at the Literature—Linking Impairments to Function

Inherent to the structure in both the ICF model and the NDT Practice Model is that impairments have a relationship to participation restrictions and activity limitations.17,18 Researchers are careful to make clear that we do not know if the relationship is causal.17,18,19,20,21,22,23 However, case reports that include examination of impairments, activity limitations, participation restrictions, and contextual factors generate hypotheses about the relationships of each of these categories. They describe intervention with measured outcomes that may assist in determining how impairments influence function (activity limitations and participation restrictions). In Ling and Fisher’s24 case report of a client 4.5 years poststroke with severe upper extremity impairments and a Fugl–Meyer upper extremity motor score of 18/66, the authors/clinicians examined impairments using standardized tests to quantify impairments and functional abilities/disabilities. They also used detailed posture and movement analysis to evaluate and plan intervention for a specific functional outcome. The outcomes were specific to the client’s participation needs. Using posture and movement analysis, the authors generated hypotheses about how single-system and multisystem impairments affected these specific functional tasks. Intervention consisted of 8 weekly 1-hour intervention sessions, and intervention strategies were described in detail.

In a study performed by Slusarski,25 40 ambulatory children with CP participated in a total of 12 hours of intervention based on NDT principles, with each child working toward individually set functional ambulation goals. In addition, pedographs measured stride and step length, foot angle, and base of support. Cadence and velocity of gait were also measured. Significant positive changes toward age appropriate gait parameters occurred for the group in stride and step length, foot angle, and velocity, with improvements also measured in base of support and cadence. In this study, the intervention strategies were not described in detail in the research report, but they were stated to be individualized for each child. The study showed that pedographs can be sensitive to gait changes in children with CP and that the group improved significantly in four of the six measures of gait toward normal parameters. Keep in mind that “normal parameters” indicate energy efficiency and more normal stresses on joints. This study linked posture and movement changes to improved gait.

Fig. 8.3 The interrelationships of all domains of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). Any number of body systems could be considered in this diagram.

Arndt et al26 studied the efficacy of an operationally defined NDT-based trunk intervention protocol on gross motor function (activity) in babies ages 4 to 12 months with posture and movement dysfunction. The protocol for trunk activity was described in the research report. These infants were compared with a group of infants exposed to a structured parent–infant play group on gains on the Gross Motor Function Measure (GMFM) after each group received 10 hours of intervention. An examiner masked to group assignment rated each infant. Both groups of infants improved their GMFM scores, but the NDT trunk protocol group increased their scores significantly (p = 0.048) more than the parent–infant play group, and maintained the skills in a 3-week follow-up. This study showed posture and movement changes linked to gains made on a standardized test.

Fig. 8.4 An example of a teenager with severe dystonia using the information in Fig. 8.3 (participation, activity, and body system integrities).

Fig. 8.5 Example of the same teenager with severe dystonia using the information in Fig. 8.3 (participation restriction, activity limitations, and body system impairments).

Linking Integrities and Impairments to Activity and Participation Using the NDT Practice Model

Clinicians using NDT have the opportunity each time they evaluate and provide intervention services to a client to hypothesize how impairments may be linked to activity and participation. Each intervention is designed and planned around a functional outcome. This outcome is recorded in the documentation, and then the clinician generates hypotheses as to what is interfering with the attainment of that outcome. Intervention is planned to address the single- and multisystem impairments and contextual factors that are hypothesized to interfere with activity and participation. NDT hypothesizes that system impairments are linked to activity limitations and participation restrictions. Multiple case reports linking or failing to link these hypotheses to function, such as the published reports by Ling and Fisher,24 Slusarski,25 and Arndt et al,26 will continue to shape intervention and refine the NDT Practice Model.

For example, Chris is a 5-year-old kindergartener who loves to play and have fun. He likes music and watching videos. He is social and engaging. He also has CP. His speech-language pathologist (SLP) notes Chris’s integrities of the abilities to speak one to two words per breath, his communicative intent in a variety of social contexts, his perseverance in attempting skills that interest him, and his intact language skills. Chris shows impairments in active control of his respiratory cycle, specifically in grading exhalation for speech that requires trunk postural muscle timing and endurance (Fig. 8.6). Chris’s SLP hypothesizes that the total body extension and laryngeal valving he uses to phonate constitute a compensatory posture and movement strategy for this respiratory control impairment. She also hypothesizes that this compensatory posture and movement strategy negatively affects alignment of Chris’s oral structures (lips, tongue, and jaw) for rapid, connected speech production and decreases his speech intelligibility for most listeners. She hypothesizes that communication in the participatory domain is restricted. She sets a functional outcome about the number of words or syllables that Chris can consistently produce per exhalation in the context of interacting with peers in kindergarten or with his siblings under particular environmental conditions. A range of prognoses from use of verbal communication in a variety of (although perhaps not all) contexts to a poorer prognosis of limited verbal communication only with people familiar with Chris is possible.

Fig. 8.6 Chris works in intervention with one of his therapists, who is addressing his rib cage position and mobility.

The outcome is set, and Chris’s SLP hypothesizes that active rib cage expansion with respirations, control of inhalation/exhalation timing and airflow through the larynx, use of postural muscle activity rather than phasic extension movements throughout the body to control airflow, and optimal alignment of oral structures will be necessary to achieve the outcome. She then selects intervention strategies to address selected single- and multisystem impairments, including ineffective postures and movements, while assisting him to practice efficient and functional postures and movements. She constantly monitors if, in fact, the posture and movement changes achieved in intervention result in the desired outcome. Evaluation is constant and ongoing throughout the intervention. Examination, evaluation, and intervention interweave and are essentially inseparable.

Chris’s occupational therapist (OT) sets a functional outcome regarding his ability to control a switch to access his computer. He attempts to reach the switch but is unsuccessful. He knows what a computer and switch can do and attempts to reach for the switch. His OT hypothesizes that the posture and movement strategy that Chris uses to reach is ineffective, however, because he is seldom successful in activating the switch, even when it is placed within his range of reach. Chris uses thoracic flexion with head and neck hyperextension, shoulder girdle elevation with scapular abduction and anterior tipping, shoulder internal rotation and adduction, elbow flexion, and forearm pronation to reach. His OT further hypothesizes that this posture and movement strategy is a compensation for impairments in several single and multisystems, notably the following:

1. Difficulty initiating and sustaining postural muscle activity in the synergy of trunk extension while grading small ranges of hip flexion/extension.

2. Lack of development of spinal, rib cage, and shoulder complex alignment to allow the possibility of using scapular stabilizers to move the scapulae out of abduction, elevation, and anterior tipping.

3. Trunk flexion with scapular position as in number 2 places the shoulder joints in a position of internal rotation and adduction, with distal components following.

4. Possible range of motion restrictions in the spine, rib cage, shoulder, elbow, forearm, and hand.

5. Decreased somatosensory awareness of upper extremity position and movement.

6. Impairments of visual perception that may interfere with accuracy of reach.

As the SLP did, Chris’s OT will structure a plan of care based on hypotheses that link single- and multisystem impairments to outcomes. She can envision a range of prognoses from little/no successful functional reach to the ability to reach and possibly use limited grasp and release with a variety of objects. As she engages Chris in intervention, she will constantly monitor the success or lack of success of her strategies. Examination, evaluation, and intervention interweave and are essentially inseparable.

Analyzing the Range of Possible Prognoses

The clinician analyzes the range of possible prognoses. Prognosis is based on the following:

1. Severity of participation restrictions, activity limitations, and impairments.

2. Responses to therapeutic intervention to change participation, activity, and impairments.

3. Contextual factors, such as attitude, determination, desire to work to change, and family, community accessibility, and monetary resources.

During each session with a client, the NDT clinician gathers information about responses to intervention and therefore can adjust the prognosis as necessary.

Example of Evaluation Overview Using a Case Report

As an example of the evaluation process, we will look at parts of the case report of Carol (Fig. 8.7) found in Unit V (A3), an adult poststroke. Information from her history, interview, and examination is summarized and prioritized in Table 8.2 and is weighed by her physical therapist (PT) as they work together to determine intervention outcomes.

Table 8.2 Problem-solving and decision-making process during Carol’s evaluation portion of clinical practice using the Neuro-Developmental Treatment Practice Model

ICF domainsa | Prioritization within each domain and explanationsb |

Contextual factors: | The contextual factors determine available facilitators and barriers, settings for intervention, and physical, emotional, social, and financial support that affects outcome decisions. Carol’s PT may be able to suggest durable medical equipment that results in outcomes for intervention that are different from outcomes if equipment is not available. This is also true for health care services—physical assistance in addition to Carol’s husband may allow more difficult postures and movements to be practiced safely and effectively. |

• Carol’s husband is determined to provide care for her in their home. | |

• Carol is a retired nurse; her husband is retired. | |

• The home is one level. | |

• New equipment is needed since the stroke: ramp over outdoor steps into house, bedrail, wheelchair, commode chair. | |

• Her husband provides daily care, including support of Carol’s efforts to do activities herself as much as possible. | |

• Her husband is emotionally supportive. | Examples: |

• Carol’s husband’s decision to care for Carol at home affects every choice of outcome—who will be assisting Carol physically and emotionally (her husband), what settings they participate in, how care will be safely performed. | |

• Carol is able to participate in partnership with her husband regarding decision making for the house, family, finances, etc. | • The couple is retired, which allows for a daily routine devoted to their personal wants and needs. |

• The one-level home affects decisions about mobility outcomes and priorities. | |

• Insurance coverage provides part-time home health care services, therapies, and equipment. | • Carol and her husband view decisions as a joint effort, and Carol’s PT will include both of them in decision making throughout the intervention. |

• No outpatient services are close to where she lives (or that she’s eligible for). | • The couple has a limited social and family network in place that may serve as resources for physical, emotional, and social support as well as participation choices. |

• Personal care attendants are not trained/allowed to transfer/practice skills with her because of her low physical abilities (i.e., she’s too low level and there are rules about how much they’re allowed to “lift”). | |

• Care aides assist with personal care and dressing every morning and evening. | |

• Carol possesses a previous social network in the community at the gym, with friends/family, at work, and through travel. | |

Participation: | • Carol is currently unable to participate in community involvement, of which physical barriers are the most restrictive, but personal issues (including her self-consciousness about drooling) are also factors. Carol, her husband, and her PT prioritize which community participation choices Carol would like to return to first. |

• Unable to perform any step of sewing for business enterprise. | |

• Unable to grocery shop, garden, attend craft fairs (business and leisure), travel long distances to visit children and grandchildren. | |

• Unable to participate in community physical exercise/mobility. | • Carol’s hobbies and routine family roles have been severely altered. Problem solving revolves around what Carol wants to try to do—what are the most important roles or parts of roles she wants to regain first? |

Activity: | • Carol is dependent on her husband for all mobility needs, and many of her activities of daily living (ADLs) routines. Carol’s PT considers the physical, social, and emotional implications on this drastic change in Carol’s daily lifestyle. |

• Eats at a table; wipes mouth with cloth; reads books/watches TV—all when set up in a wheelchair or propped in bed by husband. | |

• Dependent in all home tasks, where her current activity takes place—husband transports via wheelchair and manages all transfers, including bedside commode; in and out of bed and van; assists care aides with dressing when standing is needed. | • Carol, her husband, and the PT prioritize which activities are most important and may be the least difficult for her to work on first in intervention. Activities that affect participation outcomes will be priorities (e.g., will Carol and her husband feel car/van transfers are the first activities to focus on? or getting in/out of the pool?). |

• Unable to use sewing machine or cut out patterns. | |

Most significant system integrities: • Cognitively intact • Continence of bowel and bladder • Sensation tests as intact (light touch, pain, proprioception) • Skin intact | Carol’s system integrities allow her to make decisions about her intervention and the outcomes she desires. Continence allows a return to pool participation. Intact sensations and skin condition assist relearning of posture and movements. |

Most significant multisystem impairments: • Pushes strongly with right arm and leg to the left and backwards with any attempts to shift weight forward and up, i.e., scooting forward, sit to stand, transfers (sensory, graviceptive, perceptual systems could contribute). • Very fearful of coming forward in space (sensory and perceptual systems, and knowledge of loss of postural control and movement with experience could contribute). • Sits in a flexed trunk in all postures (neuromuscular, musculoskeletal, sensory, perceptual systems, and external seating support could all contribute). • Trunk passively elongated on the right in sitting and standing (neuromuscular, sensory, perceptual, musculoskeletal systems, and habitual positioning could contribute). • Left scapula wings and rests in downward rotation, elevation, and abduction compared to right scapula (neuromuscular and musculoskeletal systems plus disuse could contribute). • Left GH joint subluxed approximately three finger widths (neuromuscular, sensory, and musculoskeletal systems, as well as disuse, gravity, and alignment of entire body could contribute). • Muscle atrophy around left scapula and GH joint (not only musculoskeletal, but disuse and lack of full sensation could contribute). • Left hip deviates laterally > posteriorly in standing (neuromuscular, sensory, perceptual, and musculoskeletal systems could contribute). • Hyperextends left knee 100% of the time in standing and stepping (neuromuscular, musculoskeletal, sensory systems along with ground reaction forces could all contribute). • Drools, primarily from left side of mouth (sensory and neuromuscular systems, as well as body alignment could contribute). • Left fingers rest in flexion with slight wrist flexion (neuromuscular, sensory, musculoskeletal systems as well as disuse could contribute). • Holds head/neck to the left rotation and side flexed (neuromuscular, sensory, perceptual, and musculoskeletal systems could contribute). • Never attempts to use left limbs for any task, i.e., no volitionally active movement seen (neuromuscular, sensory, perceptual systems as well as learned disuse could contribute). • Left foot/ankle tends to passively invert and plantar flex, and it is difficult to position with foot flat on floor for transfers and transitions, i.e., scooting, sit to stand (neuromuscular, sensory, and musculoskeletal systems as well as gravity and body positioning could contribute). | This list of Carol’s multisystem impairments is significant because the postures, movements, and behaviors observed, measured, and perceived through handling can each have many sources that contribute. In addition to single-system structure and function that could contribute, the clinician must hypothesize about how the contextual factors contribute, and then how all of these possibilities reinforce each other. For example, as Carol sits with a flexed trunk in all postures, how are her sensory receptors adapting to this position? How do any musculoskeletal impairments that contribute to this posture become reinforced and magnified by constant asymmetrical positioning, leading to new perceptions of correct upright posture? How does the posture increase perceptual impairments over time? How do Carol’s wheelchair, commode chair, and bed contribute to increasing number or severity of impairments in all of these body systems? How does the way care aides and Carol’s husband help her perform transfers and daily care improve or increase the severity of the interaction of all these factors? |

| |

Most significant single-system impairments: Neuromuscular • Inappropriate over-activity of right lateral trunk and limb extensor muscles (UE > LE). • Decreased ability to sustain activity in spinal extensor muscles (thoracic >> lumbar and L >> R). Perceptual and Graviceptive Sensory Systems • Decreased awareness of midline primarily in frontal plane, but also in sagittal plane. Musculoskeletal • Weakness in left lateral trunk muscles. • Weakness in left hip abductors, extensors, and quadriceps muscles. • Tightness in:

Neuromuscular • Inability to initiate activity throughout left UE and scapular muscles. • Inability to initiate activity in left LE muscles other than hip abductors, extensors, and quadriceps. Cardiovascular • General cardiovascular deconditioning. Regulatory (Arousal/Attention) • Decreased attention. | This list of Carol’s single-system impairments is significant because they are hypothesized to interfere with most or all attempts at activity and participation. They are listed in order of the impairment that makes the biggest impact on activity limitations and participation restrictions. |

Abbreviations: GH, glenohumeral; ICF, International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health; PT, physical therapist.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

All neck muscles for side flexion, rotation, and long pivot extension (left > right).

All neck muscles for side flexion, rotation, and long pivot extension (left > right). Left > right soleus > gastrocnemius muscles.

Left > right soleus > gastrocnemius muscles. Right lateral trunk muscles (rotators included).

Right lateral trunk muscles (rotators included). Left shoulder (GH) internal rotators and adductors.

Left shoulder (GH) internal rotators and adductors. Left MCP and PIP flexors (especially digit 4) and long wrist flexors.

Left MCP and PIP flexors (especially digit 4) and long wrist flexors.