Chapter 75 Evaluation of the Cervical Spine after Trauma

Unrecognized injury to the cervical spine can produce catastrophic neurologic disability; clinicians are obligated to actively rule out cervical spine injury (CSI). The absence of injury is both difficult and imperative to define. Emergency departments in the United States and Canada are treating more than 13 million trauma victims annually who are at risk for CSI. The guidelines for cervical spine clearance are conflicting, and the management of patients is variable across medical institutions and different countries. Among neurologically intact patients, CSI is detected in 1%, the incidence in blunt trauma patients is 4.3%, and patients suffering a traumatic brain injury have a 5% to 10% chance of having CSI.1–4

Recent published studies examined radiation exposure as the cause of cancer. These studies extrapolate from data collected on radiation exposure and secondary malignancies in populations that experienced atomic bombing. Richards et al. compared the use of cervical radiographs combined with head CT to CT of the head and cervical spine. The calculated risk for lifetime cancer was 1:4500 and 1:2400, respectively. They concluded that as a screening procedure for a low-incidence finding, the risks might outweigh the benefits.5

Clinical Clearance of the Cervical Spine

The proper diagnosis of cervical spine trauma is considered extremely important and therefore results in the liberal use of cervical radiographs. These radiographs are easy to perform, but they expose the patient to ionizing radiation and account for substantial medical health expenses. Several small studies have suggested that patients with blunt trauma have a low probability of injury to the cervical spine if they meet all five of the following criteria: They do not have tenderness at the posterior midline of the cervical spine, they have no focal neurologic deficit, they have a normal level of alertness, they have no evidence of intoxication, and they do not have a clinically apparent, painful injury that might distract them from the pain of a CSI. These studies led to a large trial by the National Emergency X-Radiography Utilization Study Group (NEXUS) regarding criteria for clinical cervical spine clearance. A prospective observational multicenter study in 21 centers in the United States evaluated 34,069 patients with blunt trauma, of whom 4309 patients fulfilled all criteria for clinical clearance. The implementation of the criteria identified all but 8 of the 818 patients who had CSI picked by three-view radiographs. Only 2 of the 8 patients, missed by the clinical evaluation, had significant CSI. Following the outlined clinical algorithm, 12.6% of blunt trauma patients would have avoided the radiography screening.2

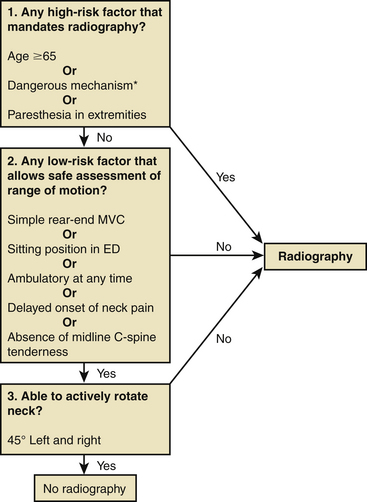

Stiell et al. proposed a different algorithm (Fig. 75-1) for cervical spine trauma. They studied 8924 patients after blunt head or neck trauma with stable vital signs and a Glasgow Coma Scale score of 15 points, of whom 151 (1.7%) had important C-spine injury. The algorithm consisted of three questions: whether the patient has high-risk factors, whether the patient has low-risk factors, and whether the patient has the ability to rotate the head. The sensitivity of this algorithm was 100% and the specificity was 42.5%, compared to three-view cervical radiograph or 2-week follow-up, reducing the radiography ordering rate to 58.2%.6

Stiell et al. compared the use of the NEXUS criteria to those of the Canadian Cervical-Spine Rule (CCR). The sensitivity and specificity for both tests were calculated after evaluation of 8283 Canadian patients suffering from head or neck trauma, 169 of whom (2%) had clinically significant spinal injury. The CCR was more sensitive than the NEXUS (99.4% vs. 90.7%, P < .001) and more specific (45.1% vs. 36.8%, P < .001) for injury, and its use would have resulted in lower radiography rates (55.9% vs. 66.6%, P < .001).4 The CCR algorithm is statistically superior but is also more complex to remember and implement, thus necessitating screening by well-trained trauma physicians. On the other hand, the NEXUS is less complex and can be utilized by physicians of various specializations.

Rethnam et al. retrospectively analyzed 114 alert trauma patients who had radiographs for cervical spine screening. If the CCR had been utilized, there would have been a 75.8% reduction in the number of patients who received radiographs, and neither of the two CSI patients would have been missed.7 Grossman et al. surveyed trauma centers in the United States and reported a wide variety of approaches to cervical spine clearance, with significant differences according to the trauma center level.1 Guidelines from the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma (EAST) are based on the NEXUS algorithm.8,9 Because the best algorithm for cervical clearance is not agreed upon, it seems prudent that trauma centers should have a consensus algorithm implemented by all trauma caregivers.

Radiologic Clearance of the Cervical Spine

Radiographs

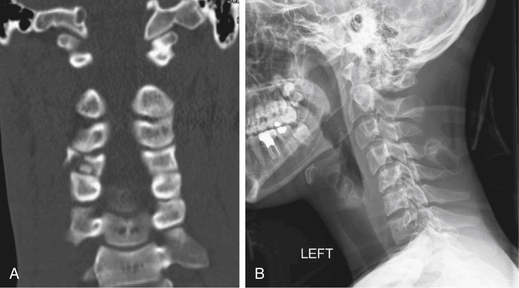

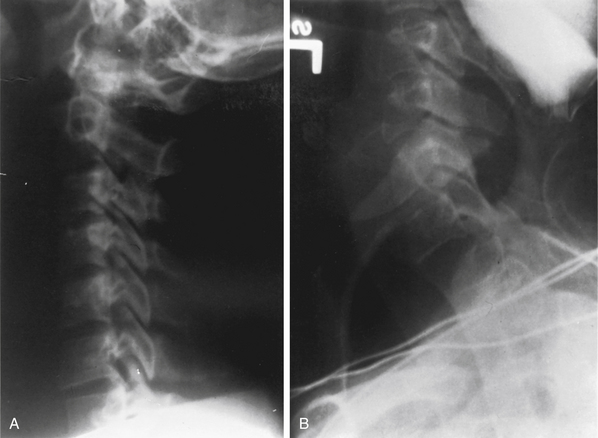

The American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma published recommendations for the initial cervical spine radiographic evaluation in trauma victims. The committee included anteroposterior (Fig. 75-2A), lateral (Fig. 75-2B), and odontoid views of the cervical spine in this evaluation. Optimally, the lateral view images the rostral aspect of the first thoracic vertebra. Lateral films were reported to identify 85% of bony pathology; the addition of anteroposterior and odontoid views increases the sensitivity to 95%.10,11 However, newer studies utilizing CT and MRI scans in addition to radiographs report a 39% to 94% sensitivity with radiograph alone.12 Some authors conclude that CT is superior to radiography as a screening tool and should be utilized routinely in severe trauma, with or without radiography.13,14 Often, conventional lateral radiographs are insufficient, and a swimmer’s view may be necessary to image the cervicothoracic junction (Fig. 75-3).

Computed Tomography

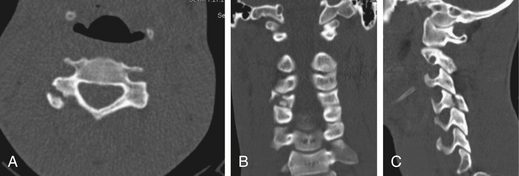

Many centers use CT as the first subsequent study following radiography. CT is fast, is readily available, and facilitates patient monitoring (Fig. 75-4). The sensitivity of CT for cervical spine fractures has been reported to be between 90% and 99%, with specificities of 72% to 89%, and studies examining the sensitivity of radiography usually consider CT scan to be the gold standard.14,15 Nunez et al. compared radiographic screening to CT screening in 88 severe trauma patients. CT depicted 32 fractures that were not identified by radiography, most at the C1-2 and C6-7 regions. One third of these were unstable or clinically important.13 Link et al. demonstrated that inclusion of the cervicocranial region in the head CT, in addition to a three-view cervical radiograph, revealed additional cervical fractures in 5% of severe head trauma patients.14 According to EAST recommendations, CT should be utilized, in addition to radiography, for all patients with insufficient imaging of a specific region or evidence of radiographic abnormality, neurologic deficit, or impaired consciousness.8,9 Patient evaluation with both radiography and CT raised the question of whether the radiographic studies were necessary. In patients with severe trauma, it is difficult to obtain high-quality radiographic studies. Furthermore, imaging the patient delays further studies that may be needed and delivers further radiation to the thyroid. Hashem et al. retrospectively examined the added value of radiography to CT, in patients with CSI admitted to a level 1 trauma center. While CT demonstrated 100% of the pathologies, the sensitivity of radiography was 61%.16 These data should be considered when the guidelines for cervical spine clearance are being updated.

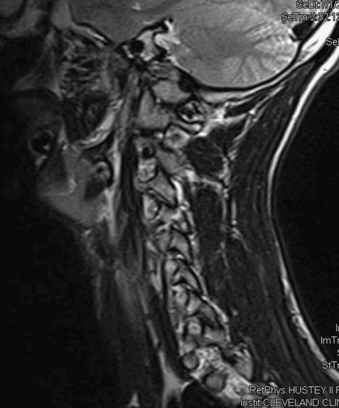

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Radiographic and CT images are very sensitive to bony anatomy but are not efficient or sensitive in the detection soft tissue injury. Occurrence of cervical spine ligamentous injury, which is potentially unstable, is estimated to be 0.04% to 0.9%17; it is a rare condition but with possible severe consequences. MRI is considered by some to be the gold standard modality for evaluation of soft tissue injury. The images can identify prevertebral hematomas, lesions pressing on the cord such as herniated discs, ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament, epidural hematoma, and spinal cord contusions or edema (Fig. 75-5). The data that are presented by MRI are a valuable diagnostic tool. Unlike CT, in which axial acquisition is reconstructed to three planes, MRI acquisition is accomplished in three planes, thus reducing the possibility of missing pathology that parallels the acquisition plane. MRI does not deliver radiation and hence reduces potential future risks for cancer. On the other hand, MRI is not always available in some trauma centers; it requires more time and personnel; it requires the use of special ventilator and monitoring techniques; and some immobilization and traction devices will not fit into the MRI or are not MRI compatible. Finally, hemodynamically or respiratory unstable patients should not undergo an MRI.12,18,19

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree