External Examination of the Head, Neck, and Spine

Ana Rubio

Acritical difference between forensic and hospital autopsies is the emphasis given to the external examination in the forensic setting1 (Fig. 3.1). Information from the scene (Case 3.1 and e-Fig 3.1) and knowledge of the clinical history guide decisions on the type of examination and procedures that will best document the nature and severity of the pathologic findings, as well as highlight pertinent negatives. Important information needs to be conveyed to the consulting neuropathologist before examination of

the brain after fixation. This chapter complements Chapter 1, providing a more detailed description of the forensic procedures that have an impact on the neuropathologic examination. We start with a general description and follow with a step-by-step examination of the head, neck, scalp, skull, and spine.

the brain after fixation. This chapter complements Chapter 1, providing a more detailed description of the forensic procedures that have an impact on the neuropathologic examination. We start with a general description and follow with a step-by-step examination of the head, neck, scalp, skull, and spine.

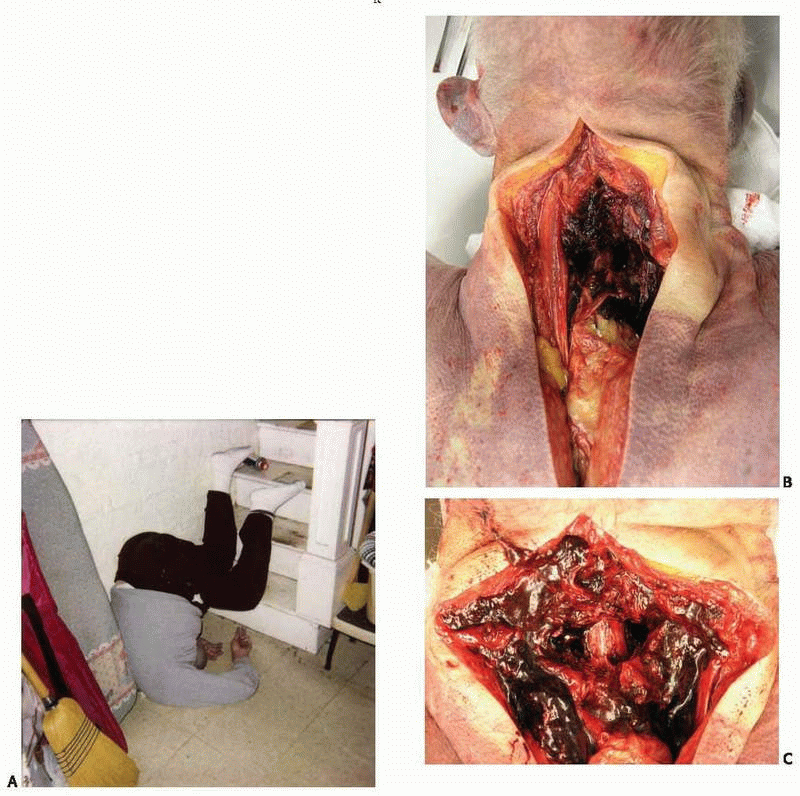

Case 3.1

An 80-year-old man was found dead by a neighbor, at the bottom of the basement stairs of his house. The neck was hyperflexed, and the body was in an upside-down position (Fig. A). A partial autopsy was performed. Although examination of the head and brain were unremarkable, a posterior neck dissection was performed to rule out neck injuries. The soft tissues and muscles of the posterior neck were hemorrhagic (Fig. B), and there were comminuted fractures of the posterior 5th and 6th cervical vertebrae, with the uncovered spinal cord exposed and contused (Fig. C). The cause of death was certified as neck injuries, and the manner of death as accident.

|

GENERAL ASPECTS OF THE EXTERNAL EXAMINATION

The purpose is to assess and document external signs that may explain or suggest internal pathology. Circumstances at the scene that are in disagreement with external or internal examination findings need to be re-evaluated or explained. Examination is primarily visual (with the aid of a dissecting microscope when necessary), but olfactory and tactile information may modify subsequent procedures. Odors may suggest urination, decomposition, infection, or the presence of alcohol or other foreign substances, such as cyanide or accelerants, in case of fire, among others. Palpation follows visual examination for determination of the integrity or abnormal consistency of tissues and organs and the presence of masses.

Scene

Information from the scene aids in the interpretation of pathologic findings. The scene may be the place of death or, alternatively, the body may have been moved before discovery (dumping). The scene may remain exactly as it was when the victim died or may have been altered by the assailant, a passerby, relatives, or friends of the victim. Friends or relatives may remove or hide personal possessions or evidence, either for personal gain or because they consider it may reflect badly on the victim or themselves. Bodies found outside may have been exposed to different environmental conditions (e-Fig. 3.1), animal predation, or human activity, either premortem or postmortem (Fig. 3.2). The location and position of the body may provide clues to explain the traumatic injuries.

Environment, temperature, and estimated postmortem interval may be critical in determining the cause and manner of death (Fig. 3.3). The accessibility of the dwelling (whether or not the house was secured, type of door lock) and living circumstances, including partners, roommates, and pets, may be important to rule out foul play or whether environmental toxins, such as carbon monoxide, may have played a role. Any details concerning the activities of the subject during the last hours of life may also be helpful. The presence of blood, body fluids, or tissues may suggest a traumatic event. Objects that may have been used as weapons can be important evidence. The scene may suggest a struggle (e-Fig. 3.2), and additional police investigation, together with a thorough search for traumatic injuries to the body to rule out nonnatural death, may be necessary.

Clothing

Visual examination continues at the morgue, beginning with the individual’s clothing (e-Fig. 3.3), as clothes may explain the presence or absence of injuries. Unyielding or hard objects, such as belts, rivets, hats, and leather coats, may either protect or damage the body depending on the circumstances, and the presence or absence of injury may only be understood by knowledge of the clothing at the time of the traumatic event (Figs. 3.4 and 3.5, e-Fig. 3.4). Clothes may protect the skin from superficial blunt force injuries, but do little to diminish the amount of force delivered to the body and transmitted internally (as in sudden decelerations of motor vehicle collisions). Dark clothing may hide important evidence, such as blood or soot. Inappropriate dressing (seasonal mismatch, improper position of clothes, partial dressing or undressing) may suggest foul play (victim being dressed postmortem), confusion or dementia (Fig. 3.6), or an environmental effect (paradoxical undressing seen in hypothermia deaths). Finally, examination of the clothes must include consideration of particular

habits or fashions, such as the custom among young people in the late 1990s of wearing T-shirts inside out or back to front (in which case a gunshot injury may be in the back, but the entrance wound would appear in the front of the T-shirt) or pants worn low on the hips.

habits or fashions, such as the custom among young people in the late 1990s of wearing T-shirts inside out or back to front (in which case a gunshot injury may be in the back, but the entrance wound would appear in the front of the T-shirt) or pants worn low on the hips.

FIG. 3.2. Rodents and carnivores can produce extensive destruction of soft tissues postmortem, resembling premortem injuries. |

Inspection of the Body

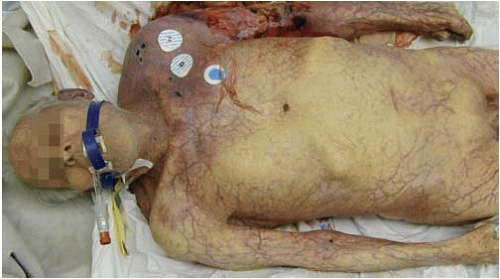

External examination of the body is initially performed before washing the skin (Fig. 3.7). Foreign bodies, blood, or secretions around the face or body orifices need to be explained (e-Figs. 3.5 and 3.6). If the findings do not correlate with the circumstances surrounding death, further investigation is warranted. Visual inspection is repeated after the body is cleaned to document individual phenotypic characteristics, social habits, signs of disease, remote or recent injuries, and treatment. Injuries may have been modified or hidden by treatment (wounds may have been cleaned, debrided, sutured, or used as an opening for treatment [Fig. 3.8]).

General Characteristics

Individual characteristics such as age, race, sex, height, weight, and type of employment are usually available. Cachexia may indicate poor health, terminal disease (cancer, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome), inability or lack of interest in caring for oneself, severe psychological abnormalities, chronic alcoholism, abuse, or neglect. Terminal retention of fluids may greatly alter the postmortem body weight. Obesity may indicate endocrine or brain pathology (e-Fig. 3.7). Excessive height may be a sign of endocrine abnormalities, including pituitary tumors, and small stature may indicate a genetic anomaly or mitochondrial disease. In most cases, a cursory evaluation does not reveal any major abnormality, and notation of the basic characteristics is all that is needed. Postmortem changes, including the pattern of lividity, are important for correlating external findings with scene investigation. The presence of body marks, either natural or tattoos, may be of help for body identification (e-Fig. 3.8).

Signs of Disease

Acute or chronic disease and effects of treatment can sometimes be inferred from the external examination. The integrity and elasticity of the skin may suggest infectious, autoimmune, or vasculitic processes; for example, gingival hypertrophy is a well known side effect of antiepileptic treatment. Skin color may give additional information (Fig. 3.9): pallor may be indicative of anemia or exsanguination; a pink (cherry red) coloration may indicate carbon monoxide intoxication, cyanide poisoning, or cold exposure; a cyanotic hue can indicate cardiac or lung disease or drug intoxication; a brown coloration may indicate methemoglobin produced in some poisonings; and a bright yellow discoloration can be indicative of liver disease or biliary obstruction.

FIG. 3.8. The star-shaped appearance of the gunshot wound to the temple is the result of surgical sutures, but resembles the star-shaped entrance of contact gunshot wounds to the skull. |

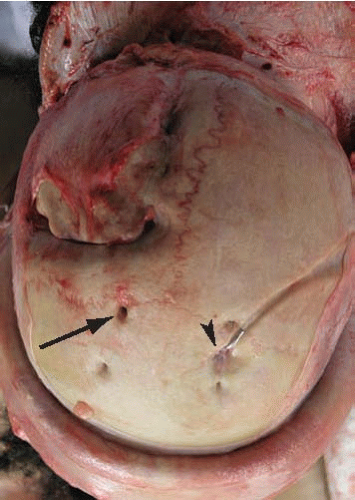

FIG. 3.10. The top of the skull shows evidence of an old craniotomy (left frontal bone), old shunt placement (left parietal, arrow), and existing subdural device (right parietal, arrowhead). |

Signs of Remote Injury

Old injuries may carry long-term sequelae that can be uncovered on examination. At other times, external evidence is lacking, and only the signs of medical intervention are found at autopsy (Fig. 3.10). It is important to obtain information regarding old injuries before autopsy, as they may determine the manner of death. If historical information is missing, healed injuries with long-lasting effects may be missed, and necessary modifications of the routine autopsy (such as obtaining blood or cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) for culture, examination of bone for the diagnosis of osteomyelitis) may be omitted. The key question during postmortem forensic evaluation is to what degree old injuries had a bearing on this person’s death. Old scars, fistulas, signs of muscular atrophy, contractures, or pressure wounds may be the only signs of remote injury or may be indicative of neglect (e-Fig. 3.9).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree