Chapter 35 Extraspinal Anatomy and Surgical Approaches to the Thoracic Spine

The thoracic spine contains more vertebrae than any other segment of the spinal column. With its 12 vertebrae, the thoracic spine is responsible for the load bearing and flexibility that has allowed Homo sapiens to stand erect. Given its critical role in the biomechanics of movement and its large contribution to the spinal column (almost a third of the total vertebrae), it is not surprising that the thoracic segment is also a frequent site of pathology (Table 35-1). Trauma, primary and metastatic tumors of the column, infections, vascular malformations, congenital disorders, and deformity all affect the thoracic column, making the ability to operate in this region an essential skill set for the competent neurosurgeon.

TABLE 35-1 Indications for Surgery

| Indication | Type |

|---|---|

| Trauma | Vertebral body fracture causing spinal cord compression |

| Infection | Tuberculosis of the vertebral body |

| Deformity | Scoliosis, kyphosis |

| Degeneration | Any type |

| Tumor | Primary and metastatic |

Anatomy

The thoracic vertebrae arise from a mesodermal origin. There are three primary centers of ossification in the cartilaginous template of the vertebra, the centrum and the two neural arches.1,2 These initial three centers of primary ossification mature into five secondary centers at the tips of the transverse processes, the spinous processes, and the annular epiphysial discs.1,2 Development of the spinal column proceeds postnatally and continues into adolescence, whereby the lordotic and kyphotic curves necessary for weight-bearing are established and completed.

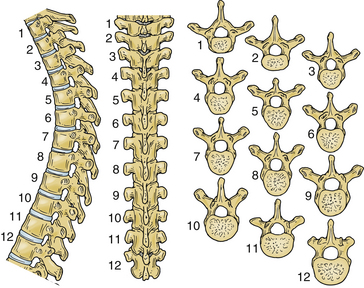

During early development, the intricate connection between the ribs and the thoracic spine begins to contour the posture of humans. The ribs articulate with the vertebral bodies via the costovertebral joints, the transverse processes via the costotransverse joints, and the pedicle of the vertebrae. As is the rule in the spinal column, the size of a vertebra increases from the cervical to the lumbar regions. Therefore the size of the thoracic vertebrae is intermediate compared with their adjacent vertebrae (Fig. 35-1).3 From T1 to T12, the length of the transverse processes decreases. The spinous processes of the thoracic vertebrae are not uniform. At the midthoracic levels, the spinous processes are long and oriented inferiorly compared with their more horizontal orientation at the lower thoracic levels. From T1 to T4, the spinal canal is heart shaped and gradually transitions to a more circular shape from T4 to T8. An imaging study of the thoracic spine frequently shows a vascular groove caused by the impression of the descending aorta. Relative to their cervical counterparts, the thoracic laminae are thicker and deeper, albeit their width is considerably decreased.4 The thoracic pedicles are short, and their height and radius increase from T1 to T12.3,5

Throughout the thoracic spine, the angle between the pedicle and midsagittal plane changes dramatically depending on the level.5 This observation has important clinical implications, such as for the placement of pedicle screws for fixation.6 At T1 the angle between the pedicle and the midsagittal plane is wide, but by T12 the pedicles are parallel to the midsagittal plane. The thoracic pedicles are shorter and thinner than their lumbar counterparts, making them more susceptible to perforation during screw placement.

The relationship between the transverse process and the pedicle is variable in the thoracic spine; this variability makes the use of intraoperative fluoroscopy a necessity for thoracic cases.7 At the upper thoracic levels, the transverse process is located rostral to the pedicle; at the lower levels, the transverse process is caudal to the pedicle with the crossover occurring at T6-7.7

From T1 to T10 the facets are oriented coronally. The orientation becomes oblique between T10 and T12.8 The coronal orientation is important for flexion-extension movements in the lower thoracic spine. The thickness and width of the laminae overlying the facets increase as they progress from rostral to caudal in the thoracic spine. Throughout the thoracic levels, the short and broad laminae in the upper and middle thoracic spine prevent hyperextension.3 The multitude of ligamentous connections, most notably the anterior longitudinal ligament, provides additional stability by increasing the tensile strength of the column. The articular surface of the superior facets is on the ventral aspect, whereas the articular surface of the inferior facets is dorsal. The articular surfaces of the facet joints are flat and slope in an oblique coronal plane, in the same plane as the lamina.

Approaches

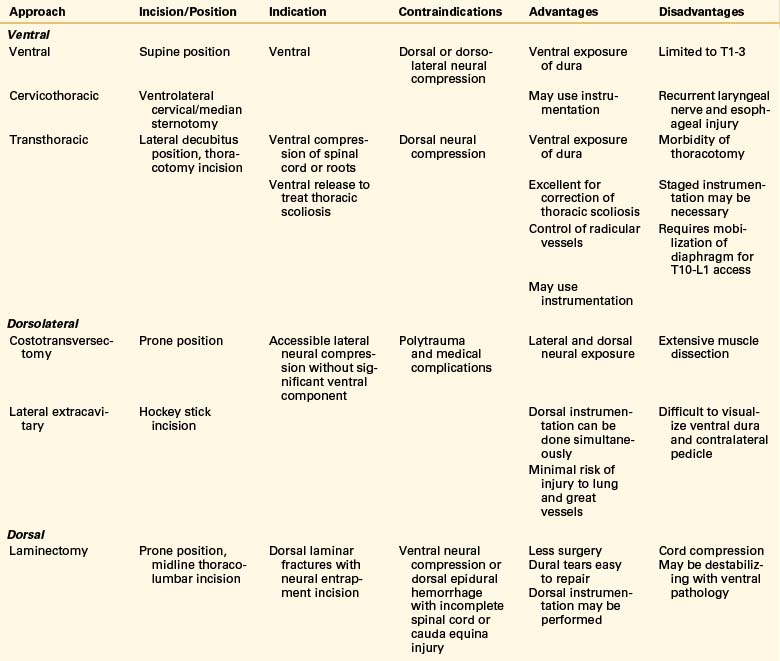

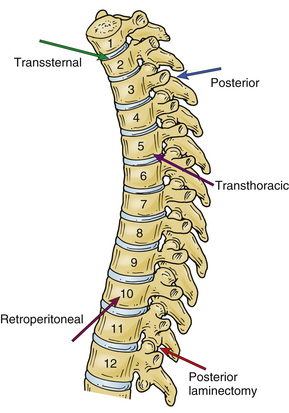

The choice of the approach to the thoracic spine largely depends on the location of the pathology that the surgeon is treating (Tables 35-2 and 35-3; Fig. 35-2). Traditionally, the operative technique of choice for treatment of pathology involving the thoracic spine has been laminectomy. Although this approach is useful for reaching dorsal pathology, it can cause great damage if used to treat ventral lesions.9,10 With the recent advent of novel microsurgical techniques and hardware for ventral stabilization, ventral approaches have become commonplace for the treatment of ventral pathology.

TABLE 35-2 Approaches to the Thoracic Spine as a Function of Level of Pathology

| Approach | Vertebral Level |

|---|---|

| Standard ventral cervical | T1-4 |

| Transsternal | T1-4 |

| Transthoracic | T3-11 |

| Transthoracic, transdiaphragmatic, retroperitoneal | T11-L1 |

Dorsal Approaches

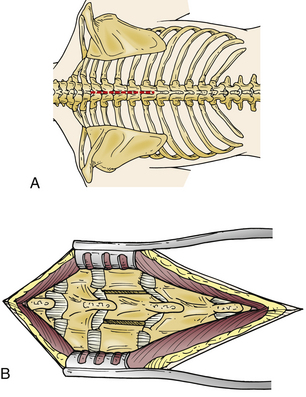

The skin is incised in the midline above the spinous process, and the subcutaneous tissue is dissected (Fig. 35-3A). The thoracolumbar fascia is incised with electrocautery. The paraspinal muscles are detached subperiosteally from the spinous process and lamina (Fig. 35-3B). A sponge may be used to perform the blunt dissection of the paraspinal muscles laterally. The sponge may also be used to control bleeding. During the blunt dissection it is important to ensure that the joint capsule of the facet is not damaged.

Ventral Surgical Approaches

Historically, the impetus for the development of spinal approaches and stabilization was the treatment of trauma, tumors, and Pott disease caused by the tuberculosis pandemics of the late 1800s and early 1900s. Hodgson and Stock described the first ventral approach with an acceptable morbidity rate of 2.9% for the debridement of a tuberculosis abscess.11

The ventral approaches can be divided on the basis of the level on the thoracic column that they reach (see Table 35-2). Generally, the higher thoracic levels (T1-3) are readily accessible using a standard ventral cervical approach, occasionally extended with a median sternotomy or sternal window. This approach is excellent for ventrally located disease with minimal paraspinal involvement. The T2-11 vertebrae can be approached through a dorsolateral thoracotomy, usually from the left side to avoid the liver and azygos vein. However, some surgeons prefer the right-sided approach to avoid the aorta. When the approach is used to correct a deformity, the rule is to use the side of the apex or convexity of the curve to allow application of interbody devices. The lower thoracic region and the thoracolumbar junction can be approached via a left thoracotomy combined with dorsal detachment of the diaphragm via a retroperitoneal approach. Again, the preference of the side depends on the surgeon’s comfort and the location of the pathology.

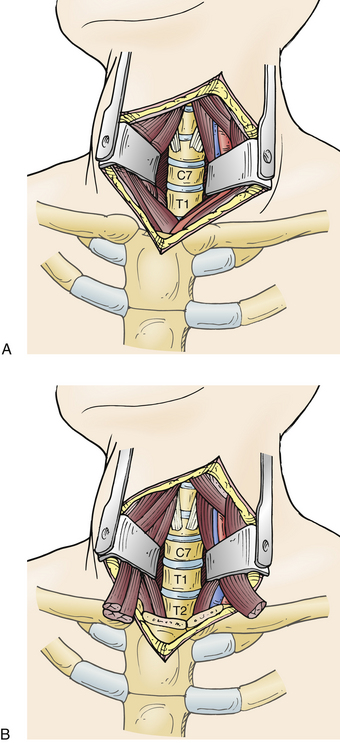

Cervical Exposure with a Median Sternotomy/Transmanubrial Approach

The high thoracic levels can be accessed via a standard cervical approach (Fig. 35-4A). A cervical approach paralleling the medial border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle is usually appropriate for T1 and T2 lesions. A medial sternotomy or sternal osteotomy is occasionally necessary to extend the surgical field to the level of T3 or T4. Most surgeons prefer a left-sided approach, which lowers the risk of injury to the recurrent laryngeal nerve on this side.12 A preoperative CT scan can be helpful in determining the relationship of the clavicle and sternum to the spine and for planning purposes.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree