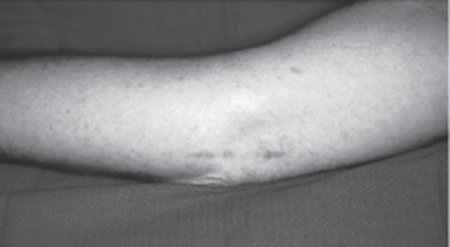

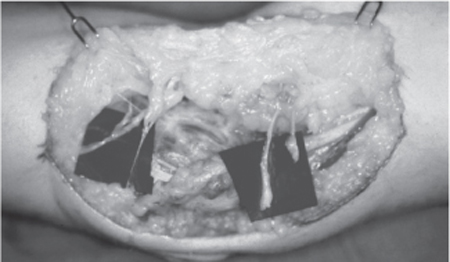

29 Failed Ulnar Nerve Decompression A 43-year-old, right-hand-dominant secretary presented 4 months after her original surgery with the diagnosis of recurrent right ulnar nerve compression at the elbow. In June 1999, she had undergone a right carpal tunnel release and a right ulnar nerve release at the elbow and wrist. Pre-operative electrodiagnostic studies demonstrated bilateral ulnar nerve compression at the elbows and mild right carpal tunnel disease. The patient had first noticed symptoms of bilateral ulnar nerve compression in 1996. Prior to her surgery she had noted intrinsic atrophy in her right hand. At that time her symptoms were paresthesias in the distribution of the ulnar nerve and difficulty with fine motor skills of the right hand. She had trouble typing and “clumsiness” with manipulation of small objects. After her surgery in 1999, her symptoms did not improve. The sensory disturbance persisted as before, and she noticed new pain in the posterior lateral elbow and the ulnar side of the wrist. She also noted an inability to abduct her right index finger following the surgery. On presentation to our office in October 1999 the patient’s sensory complaints were unchanged. Intrinsic weakness was present, but she was now able to abduct the right index finger. Four months of physical therapy had improved range of motion, but it had not improved her sensory symptoms. Numbness was reported in the small and ring fingers and the hypothenar region of the right hand. She reported constant aching in the right ulnar wrist and right lateral epicondyle increased with activity. She also had occasional pain in the right suprascapular region and often awoke at night with numbness in her right hand associated with “swelling.” She described her pain in the right upper extremity as a 6 or 7 out of 10, and has been unable to work since April 1999. Physical examination demonstrated a short, 3 cm, well-healed surgical scar (Fig. 29–1). She had pain with pressure to the region of the surgical incision. Her right hand pinch and grip were 8 and 45, as compared with 15 and 65 for the left hand. Moving and static two-point discrimination was between 4 and 5 mm in the median distributions bilaterally and in the left ulnar distribution. However, in the right ulnar nerve distribution the moving and static two-point discrimination was 7 and 8, respectively. There was a Tinel sign present over both ulnar nerves at the elbow, but the Tinel sign was much more prominent on the right side. The elbow flexion test was positive on the right side as well. There was marked atrophy of her ulnar intrinsic muscles, hand clawing, and a positive Froment paper sign in the right hand. Electrodiagnostic studies and electromyography (EMG) demonstrated persistent slowing across the elbow on both sides. The patient requested surgical intervention in the right arm first because her symptoms were far worse on that side. Figure 29–1 Patient’s preoperative scar following failed ulnar nerve release at the elbow. Failed ulnar nerve decompression All potential points of ulnar nerve compression must be recognized and examined to ensure the proper diagnosis and treatment of recurrent ulnar compression at the elbow. The ulnar nerve runs on the posterior and medial aspects of the upper arm. It travels between the brachialis and the medial head of the triceps posterior to the medial intermuscular septum. At this point the ulnar nerve is most easily found during surgical exploration. At the elbow, the ulnar nerve runs posterior to the medial epicondyle in the postcondylar groove of the olecranon. A dense fascia forms a roof over the nerve in the postcondylar groove. The cubital tunnel begins with this fascia and ends at the two heads of the flexor carpi ulnaris. The Osborne band is composed of the leading edge of the fascia that connects the ulnar and humeral heads of the flexor carpi ulnaris. Next, the ulnar nerve travels deep to the flexor carpi ulnaris and the flexor digitorum superficialis above the flexor digitorum profundus to the wrist. At the wrist the ulnar nerve is positioned ulnar to the ulnar artery as it enters the Guyon canal. The medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve (MABC) is a terminal branch of the medial cord of the brachial plexus. It typically has an anterior and a posterior branch that run distal and proximal to the medial epicondyle. Both branches are at risk during ulnar nerve release at the elbow. A small surgical incision may limit a surgeon’s ability to clearly identify the small branches of the MABC. Persistent pain following surgery for ulnar nerve compression at the elbow may be due to an injury to a branch or multiple branches of the antebrachial cutaneous nerve. The manifestation of injury to the MABC includes hypesthesia, painful scarring, and hyperalgesia. The MABC can be examined by gently tapping along its course adjacent to the basilic vein just medial to the biceps tendon. A Tinel-like response will be elicited ˜5 to 6 cm proximal to a painful neuroma in the distribution of the MABC. Patients experience altered sensibility in the medial aspects of the forearm and have no altered sensibility in the ulnar aspects of the hand. The exact point of compression at the elbow is often unknown. The ulnar nerve normally undergoes repeated friction, traction, and compression with elbow flexion. The physiological stress applied to the ulnar nerve during normal activity demonstrates the true resiliency of the ulnar nerve. Ulnar nerve compression at the elbow is a dynamic process that increases and decreases depending on the position of the elbow. Elbow flexion decreases the area within the cubital tunnel by up to 55%. Others have demonstrated that the intraneural pressure within the cubital tunnel is increased by 600% with the wrist extended, elbow flexed, and shoulder abducted. The ulnar nerve increases 4.7 mm in length as the elbow flexes. If the ulnar nerve does not elongate because of inflammation or compression the intraneural pressure will increase with elbow flexion. Five main points of compression have been reported in the region of the elbow. No surgery for ulnar nerve compression at the elbow is complete without a full assessment of each potential point of compression. Although its existence has been refuted, the arcade of Struther has been described as a thick fascial structure between the medial head of the triceps and medial intermuscular septum. The medial intermuscular septum is the next potential point of ulnar nerve compression, often seen following a previous anterior transposition of the ulnar nerve. The cubital tunnel is where the ulnar nerve travels from superficial to deep within the flexor-pronator mass. The two heads of the flexor carpi ulnaris form the arcuate ligament of Osborne. Finally, the ulnar nerve can also be compressed as it passes through the aponeurosis of the flexor-pronator mass. Instability of the ulnar nerve can result in subluxation of the nerve at the medial epicondyle. Subluxation of the ulnar nerve may occur in 16% of the normal population. Hypermobility of the ulnar nerve at the elbow appears to be associated with ulnar neuropathy by increasing the susceptibility of the nerve to trauma or frictional injury. A hypermobile triceps muscle may contribute to the problem as well. The anconeus epitrochlearis is a muscle thought to cause compression in the region of the cubital tunnel. This muscle may be present in up to 30% of patients. Space-occupying lesions, arthritis, synovitis, and trauma have all been described as potential causes of the disease. Acute compression of the nerve at the elbow may also result from even proper positioning and padding of the ulnar nerve during surgery. Patients with ulnar nerve compression at the elbow usually have numbness and tingling in the small and ring fingers. A small number of patients report aching and pain in the forearm and elbow region. The sensory changes are noted during elbow flexion and first experienced at night. Sensory deficits usually precede loss of motor function, but patients often complain of a loss of fine motor skills early. Patients who have failed ulnar nerve release at the elbow do not experience symptomatic improvement following surgery. Moreover, the sensory disturbances often become worse following surgery. A severely painful surgical scar may be the result of an injury to the MABC. When evaluating a patient for ulnar nerve compression at the elbow all potential upper extremity disease and compressive syndromes should be ruled out by a complete physical examination and electrodiagnostic studies. Two-point discrimination, pinch and grip strength, and motor strength should be fully evaluated. Maneuvers used to evaluate points of nerve compression include a Tinel sign and provocative tests. A positive response will result in tingling, “electrical shock,” or alteration of sensation in the distribution of the involved nerve. Axonal damage can be presumed with a Tinel sign. Patients who have experienced enough nerve injury to result in Wallerian degeneration will have a Tinel sign at the level of the regeneration or injury. The Tinel sign can be elicited by applying four to six manual taps over the ulnar nerve at the brachial plexus, elbow, or wrist. A provocative test is preformed at the distal wrist crease to examine for compression at the Guyon canal. The flexion/pressure test at the elbow is the most accurate provocative test at the elbow. The elbow should be flexed with the wrist and forearm placed in neutral, and manual pressure is applied to the ulnar nerve just proximal to the cubital tunnel. Brachial plexus compression can be identified by elevating the arms to increase the pressure on the brachial plexus. A positive response occurs when the patient notes sensory alterations in the hands with the arms raised over the head with the wrist in neutral and elbows extended. A Spurling test is used to rule out cervical root compression. Axial compression is applied to the head in slight extension to the right or left. Paresthesias or a sensation of electrical shock requires further evaluation of the cervical spine. The differential diagnosis of recurrent ulnar nerve compression at the elbow is a difficult task. A patient who has undergone multiple upper extremity procedures may have several potential problems. The differential diagnosis includes recurrent ulnar neuropathy, polyneuropathies, multiple crush syndromes, cutaneous neuromas, and, rarely, motor neuron disease. Other non-neurological conditions that may disguise themselves as recurrent ulnar nerve neuropathy may be rotator cuff syndrome, localized tendonitis (medial or lateral epicondylitis), or a subluxing triceps muscle or tendon. The diagnosis is more commonly confused with cervical disk disease, thoracic outlet syndrome, or ulnar nerve compression at the wrist. Multiple nerve entrapments often cloud the definitive diagnosis of ulnar nerve compression at the elbow. Electrodiagnostic studies are a valuable tool that can be used to confirm the diagnosis of recurrent ulnar nerve compression at the elbow. These studies may also be used to help determine the severity of the disease, localize the area of compression, and rule out other sites of compression or neuropathy. For cubital tunnel syndrome, preoperative and postoperative electrodiagnostic studies should be compared. Some authors do not obtain electrodiagnostic studies prior to primary cubital tunnel surgery. Other authors only operate on patients with documented evidence of disease. In patients with ulnar nerve compression at the elbow we recommend conservative management for 6 months if motor conduction velocity is above 40 m/s. However, patients with significant pain with normal electrodiagnostic studies are not necessarily denied surgery. A standard electrodiagnostic study includes sensory and motor components. Most investigators believe that motor conduction velocities across the elbow are the most useful in confirming the diagnosis of ulnar nerve compression at the elbow. There is no decrease in motor conduction velocity that is diagnostic of cubital tunnel syndrome. We believe that any value less than 50 m/s across the elbow is abnormal. However, EMG that demonstrates fibrillation in the ulnar intrinsics may help identify the disease in patients with normal conduction velocities. Improvement in the electrodiagnostic studies may not be seen following cubital tunnel syndrome. This is why it may be difficult to diagnose recurrent disease based solely on this study. Several studies note that postoperative electrodiagnostic studies do not correlate with clinical outcome. A failure of the electrodiagnostic studies to improve following surgery may be due to axonal loss secondary to chronic nerve entrapments. Patients who are evaluated following a previous ulnar nerve release at the elbow should be treated conservatively for at least 6 months. If the patient’s symptoms persist a repeat electrodiagnostic study should be performed. Motor conduction velocities across the elbow should be compared with previous studies if available. Patients with motor conduction velocity across the elbow greater than 40 m/s are followed closely for 8 more weeks. However, if the patient’s symptoms continue, elective surgery is planned. Patients with motor conduction velocities below 40 m/s are usually scheduled for elective surgery. Those below 30 m/s should undergo surgery within 6 months, and those below 20 m/s should have surgery as soon as possible. Recurrent cubital tunnel syndrome is more easily understood by knowing the procedure or technique used in the previous operation. We have not reoperated on any patients who have undergone our transmuscular transposition for primary disease. Nevertheless, we believe that patients with a small incision, limited release, subcutaneous transposition, or classic “Learmonth” submuscular transposition are good candidates for repeat exploration. We use a modification of our transmuscular transposition in all repeat surgeries. All patients diagnosed with recurrent ulnar nerve entrapment at the elbow receive conservative therapy first. The treatment is aimed at activity modifications to improve symptoms and stop disease progression. Patients with mild to moderate symptoms of ulnar nerve compression are more likely to benefit from nonoperative management. Patients are shown how the ulnar lies in a vulnerable position at the elbow and to avoid direct pressure to the region. They are taught that the ulnar nerve is loose just like the overlying skin when the elbow is straight, and tight just like the overlying skin when the elbow is flexed. Patients who experience nighttime symptoms of ulnar nerve compression at the elbow are encouraged to straighten their arms at night and to wear soft elbow pads for protection. Initially, elbow pads are worn during the day and then primarily at night. Activity modification to improve ulnar nerve compression at the elbow includes the use of a headset for those who frequently use the phone. Work stations should be modified to avoid flexion of the elbows during writing or using keyboards. The best position is wrist neutral, elbows flexed 30 degrees, and shoulders ad-ducted. Stretching exercises focusing on the flexor carpi ulnaris muscle are often helpful, but stretching should be slowly increased based on patient comfort. Recurrent ulnar nerve entrapment at the elbow is most often treated with submuscular transposition or a modification of the technique. Failed ulnar nerve release of the elbow is usually the result of an incomplete release, especially at the intermuscular septum. Rogers et al reported 14 cases of failed ulnar nerve compression at the elbow. They reported failure to resect the intermuscular septum in 12, injury to the MABC in seven, fibrosis in five, and recurrent subluxation in one. All patients improved after anterior submuscular transposition. We have found that the majority of failures related to ulnar nerve compression at the elbow are the fascia from the flexor pronator mass or painful neuromas along the MABC. The operative technique most often associated with failed ulnar nerve release at the elbow is not completely clear. Gabel and Amadio operated on 30 patients with recurrent disease. They reported two recurrences following medial epicondylectomy, three following submuscular transposition, four following simple decompression, six following internal neurolysis, six following simple decompression, and 25 following subcutaneous transposition. We have found that the majority of failures follow subcutaneous transposition. The treatment of failed ulnar nerve release at the elbow requires a consistent and thorough preoperative evaluation. Previous operative reports will assist the surgeon in the operative plan, but no assumptions should be made about the course of the ulnar nerve. We prefer to use a modification of the submuscular transposition that we have described as the “transmuscular” transposition, which includes a myofascial lengthening of the flexor pronator mass. In our experience anterior transmuscular transposition with early postoperative range of motion provides the best clinical results for failed ulnar nerve release at the elbow. It provides a fresh muscular bed for the ulnar nerve with a complete release of all potential points of compression. It is often difficult to know if the recurrence is the result of incomplete release or postoperative scarring. Our technique for redoing ulnar nerve compression at the elbow is essentially the same as our technique for primary disease. The technique reached full maturity after 2 decades and has not been modified in the past 5 years. The transmuscular transposition is an attempt to apply the best components of various techniques to achieve a consistently good clinical result. A review of the technique demonstrated 77% of 86 cases significantly improved after surgery. The results have not significantly changed for “redo” surgery performed on patients originally operated on at another institution. The surgery is usually performed under general endotracheal anesthesia, but regional anesthesia is acceptable. After the tourniquet is inflated intravenous bretylium (1.25 mg/kg lean body weight) is given to decrease the risk of postoperative pain syndromes. A longitudinal incision through the previous scar is made both proximally and distally into normal tissue. The soft tissue is carefully dissected and the branches of the MABC (or neuromas) are identified (Fig. 29–2). If a neuroma is found it is excised and the end of the nerve is cauterized and transposed into the muscle of the upper arm.

Case Presentation

Case Presentation

Diagnosis

Diagnosis

Anatomy

Anatomy

Characteristic Clinical Presentation

Characteristic Clinical Presentation

Differential Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

Diagnostic Tests

Diagnostic Tests

Management Options

Management Options

Surgical Treatment

Surgical Treatment

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree