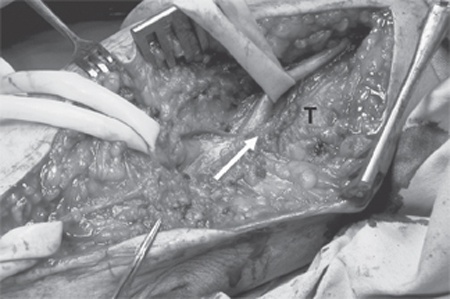

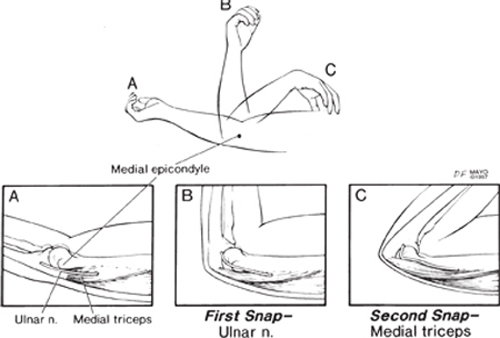

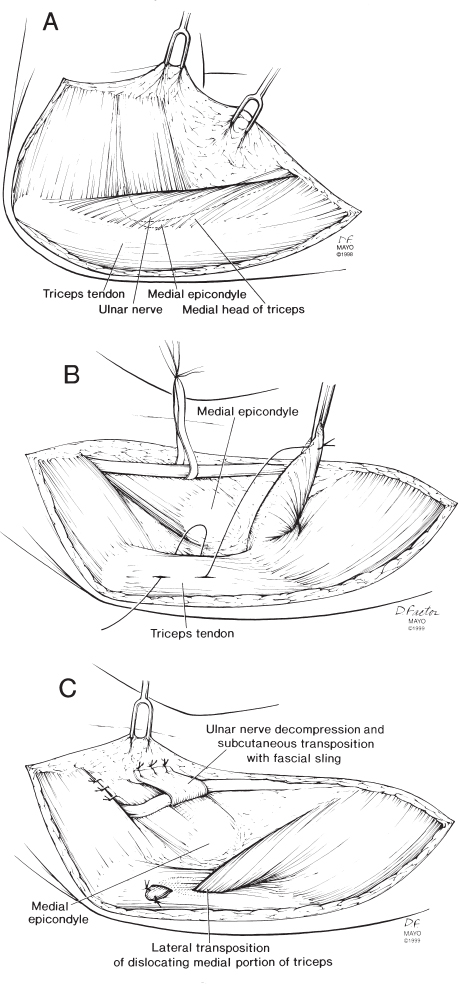

26 Failed Ulnar Nerve Transposition Due to Unrecognized Snapping of the Medial Triceps A 40-year-old psychiatrist presented with increasingly troublesome paresthesias in the ulnar 1½ digits of the dominant left hand accompanied by moderate elbow pain and snapping along the medial aspect of the elbow. He first noted the ulnar nerve symptoms and to a lesser degree, the snapping, 25 years earlier when, in high school, he swam the breast stroke for more than 75 m. As a medical student, he demonstrated his own elbow snapping in anatomy class, which he attributed to a dislocating ulnar nerve. Symptoms worsened in the 6 months prior to evaluation when they began to interfere with his physical activities (such as hockey playing) and routine household chores (e.g., closing a garage door). Physical examination demonstrated mild ulnar intrinsic weakness and sensory disturbance in the ulnar nerve distribution. He had tenderness to palpation over the ulnar nerve in the cubital tunnel. The treating physician noted that with elbow flexion, the ulnar nerve dislocated. Electrodiagnostic studies revealed a mild ulnar neuropathy. He underwent subcutaneous transposition of the ulnar nerve for presumed ulnar nerve dislocation and ulnar neuritis after a course of nonoperative therapy failed to improve his symptoms. Soon after his surgery, he noted persistent elbow snapping and ulnar nerve symptoms. Examination by a new physician revealed a prominent snap of the triceps over the medial epicondyle at ˜115 degrees. The ulnar nerve was thought to be stable in its anterior position. In fact, the patient then first noticed that he could see and feel two distinct snaps in the contralateral elbow: the ulnar nerve at ˜80 degrees and the triceps at 115 degrees. At repeat surgery of the left elbow, an anomalous tendinous slip of the medial triceps was identified that inserted more medially onto the olecranon than normally (Fig. 26–1). This band and a portion of the medial head of triceps dislocated quite prominently over the medial epicondyle with the elbow flexed and further compressed the ulnar nerve. In the flexed position, the triceps irritated the ulnar nerve in its anterior (transposed) position. A portion of the triceps was resected, and this eliminated the snapping. Neurolysis of the ulnar nerve was performed. At 1-year follow-up, the snapping and the ulnar nerve symptoms had resolved completely on the left side, but, in the interim, had developed on the right. The patient was able to tolerate these new symptoms by avoiding activities with sustained or repetitive elbow flexion. Ulnar nerve compression and irritation by snapping triceps at elbow Figure 26–1 The anteriorly transposed left ulnar nerve (Penrose drain on right) is seen up against a compressive fascial and tendinous band ( arrow), which is contiguous with the medial head of the triceps muscle (T). This anomalous band (seen over the shaft of the arrow) courses just below the medial epicondyle and inserts onto the medial portion of the olecranon. Here, even with the elbow extended, the close relationship of the tendinous slip with the medial epicondyle and the ulnar nerve is visualized. With elbow flexion, the fascial band dislocated (snapped) over the medial epicondyle, and dynamic compression of the ulnar nerve was more pronounced. The medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve (Pen-rose drains on left) is preserved. Snapping triceps is bilateral in about a third of cases and occurs in men more frequently than in women. Anatomical variations of the distal triceps muscle or tendon, or the elbow bony anatomy is responsible for its dislocation (snapping). Triceps variations may be congenital due to an accessory band or tendon (as illustrated here), supernumerary triceps, or a prominent medial head of the triceps. The most common cause is developmental, related to hypertrophied muscles in athletes. Bony abnormalities such as a cubitus varus deformity (either congenitally or posttraumatic following childhood supracondylar humeral malunion), also predispose to this condition by displacing the triceps line of pull medially. Secondary changes from a bony deformity, such as a hypoplastic medial epicondyle, may further predispose a patient to snapping. Dislocation of the ulnar nerve is a well-known anatomical variation. The prevalence of snapping of the triceps is not known. Snapping triceps was probably also present (but not detected) in some of the patients found to have dislocating ulnar nerves in often-cited population studies on the prevalence of ulnar nerve dislocation. Snapping of the triceps occurs as a portion of the medial triceps dislocates over the medial epicondyle as the elbow is flexed or extended from a fully flexed position. Typically the ulnar nerve dislocates as well as it is pushed medially by the medial triceps, sometimes resulting in ulnar neuropathy. The clinical syndrome of snapping triceps and a dislocating ulnar nerve has a characteristic clinical history, physical examination, and intraoperative appearance. Snapping triceps along with a dislocating ulnar nerve is becoming increasingly recognized. Physicians need to consider this entity anytime there is snapping at the medial aspect of the elbow, especially with ulnar neuropathy. Persistent snapping after previous ulnar nerve transposition (performed for ulnar nerve dislocation and neuropathy) is not rare and demonstrates that this condition is often misdiagnosed, and, as a result, incompletely treated. Figure 26–2 (A) Drawing shows the ulnar nerve and the triceps posterior to the medial epicondyle in full flexion. (B) The ulnar nerve dislocates beyond ˜90 degrees and (C) a portion of the medial head of the triceps dislocates beyond 115 degrees. (By permission of Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research. All rights reserved. Previously published in Spinner RJ, O’Driscoll SW, Jupiter JB, Goldner RD. Unrecognized dislocation of the medial portion of the triceps: another cause of failed ulnar nerve transposition. J Neurosurg 2000;92:52–57. Reproduced with permission.) Patients with a snapping triceps may present with medial elbow pain, snapping, ulnar nerve symptoms, or a combination of these. Patients may not necessarily have painful snapping but are curious as to the etiology of the clicking sensation in their elbow(s). Other times, patients may be completely asymptomatic, and the snapping may be detected incidentally on physical examination alone. Typically the symptoms are intermittent and are exacerbated by activities that require repeated or resisted elbow flexion. These activities may include push-ups, weightlifting, or swimming. In particular, specific phases or techniques (e.g., curling, breaststroke) may reproduce the symptoms. The ulnar nerve symptoms typically involve sensory disturbance rather than muscle weakness and are due to friction, irritation, or dynamic compression of the ulnar nerve by the triceps. The elbow pain may be due to the ulnar neuropathy itself or to a local bursitis near the medial epicondyle by the repetitive snapping. The diagnosis of snapping triceps with a dislocating ulnar nerve (with or without ulnar neuropathy) can be established on physical examination and must be distinguished from an isolated dislocating ulnar nerve. A coexisting snapping triceps should be considered in any patient found to have a dislocating ulnar nerve. Careful physical examination of the medial aspect of the elbow can determine the snap(s). In snapping triceps, two distinct snaps can usually be palpated when the patient actively flexes or extends the elbow from a flexed position, or when the physician passively flexes and extends the patient’s elbow. The ulnar nerve dislocates at ˜90 degrees, and the triceps at 115 degrees (Fig. 26–2). Occasionally, the snapping structures can be visualized as well as heard. We prefer to identify the ulnar nerve more proximally by palpating it above the cubital tunnel and then tracing it distally into the cubital tunnel. With the nerve isolated, we check for another snapping structure, specifically a muscle/tendinous band rather than a nerve. We then test for snapping by loading the triceps; the patient extends the elbow against resistance, and when possible, performs a push-up, with the examiner palpating the medial structures. Careful neurological examination may reveal mild sensory abnormalities in the ulnar side of the hand but typically does not reveal marked motor weakness. The ulnar nerve may be irritable during elbow flexion as demonstrated by percussion over the nerve or by performing the elbow flexion test. The snapping triceps often goes undiagnosed or misdiagnosed by several physicians. Snapping at the elbow is often presumed to be due to an isolated dislocating ulnar nerve. The mild ulnar nerve symptoms that often accompany the snapping lead the physician to a diagnosis of ulnar nerve dislocation with neuritis. Other times, the medial elbow pain, which can be localized to the medial epicondyle, leads to the diagnosis of medial epicondylitis (golfer’s elbow), or medial collateral ligament injury, or the clicking suggests intra-articular pathology (e.g., loose bodies or joint mice). Electrical studies in these patients are often normal or show mild evidence of ulnar neuropathy localized to the elbow. Other tests may be performed to identify the snapping structures specifically. These may include ultrasound, or axial imaging with computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Because the snapping is a dynamic process, these tests should be performed with the elbow extended and fully flexed. A trial of nonoperative therapy may alleviate acute symptoms from the snapping triceps or the ulnar neuropathy. This may include use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents or splinting the elbow in ˜70 degrees of flexion, either full time or at night. Frequently, symptoms may improve by avoiding exacerbating activities or positions. Surgery is indicated for persistent, disturbing symptoms or worsening ulnar neuropathy despite a trial of nonoperative therapy. Surgery should confirm or establish the diagnosis of a snapping triceps and a dislocating ulnar nerve (even in cases where the diagnosis was not made preoperatively). The snapping structures can be identified intraoperatively by sequential passive flexion and extension of the elbow. Operative treatment must address three components: the dislocating ulnar nerve; the ulnar neuropathy, if present; and the snapping triceps (Figs. 26–3 and 26–4). Neurolysis of the ulnar nerve should be performed first, and all potential compressive sites should be eliminated. We believe that any structure that could result in a snapping sensation should be eliminated. In this regard, we recommend either a subcutaneous or a submuscular transposition of the ulnar nerve, as the surgeon favors. A portion of the medial intermuscular septum should be resected. The ulnar nerve should pass in a straight line in its transposed position without any kinking. Finally, the dislocating portion of the triceps can be excised or transposed laterally. We prefer excision of the triceps when only a small portion of the triceps is dislocating. When the dislocating triceps is more substantial, we weave the dislocating portion through the central tendon and secure it using strong nonabsorbing suture. At the end of the procedure (and any operation with a dislocating ulnar nerve), the surgeon must ensure that there is no residual snapping and ulnar nerve compression by flexing/extending the patient’s elbow. Surgery for persistent snapping after ulnar nerve transposition is typically due to unrecognized snapping of the triceps rather than a recurrent dislocating ulnar nerve. In these cases, treatment of the dislocating triceps addresses the symptoms of snapping or elbow pain. If persistent ulnar nerve symptoms exist, then the ulnar nerve must be considered as well. Note that a dislocating triceps can dislocate anteriorly enough with full elbow flexion to irritate or compress the ulnar nerve, which has been transposed anteriorly (as illustrated in our case). If the triceps seems to be the inciting agent for the nerve irritation, then correction of the triceps pathology will adequately address the nerve as well. We favor submuscular transposition in patients with recurrent ulnar nerve symptoms after a previous subcutaneous transposition that is found to have scarring around the nerve.

Case Presentation

Case Presentation

Diagnosis

Diagnosis

Anatomy

Anatomy

Characteristic Clinical Presentation

Characteristic Clinical Presentation

Differential Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

Diagnostic Tests

Diagnostic Tests

Management Options

Management Options

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree