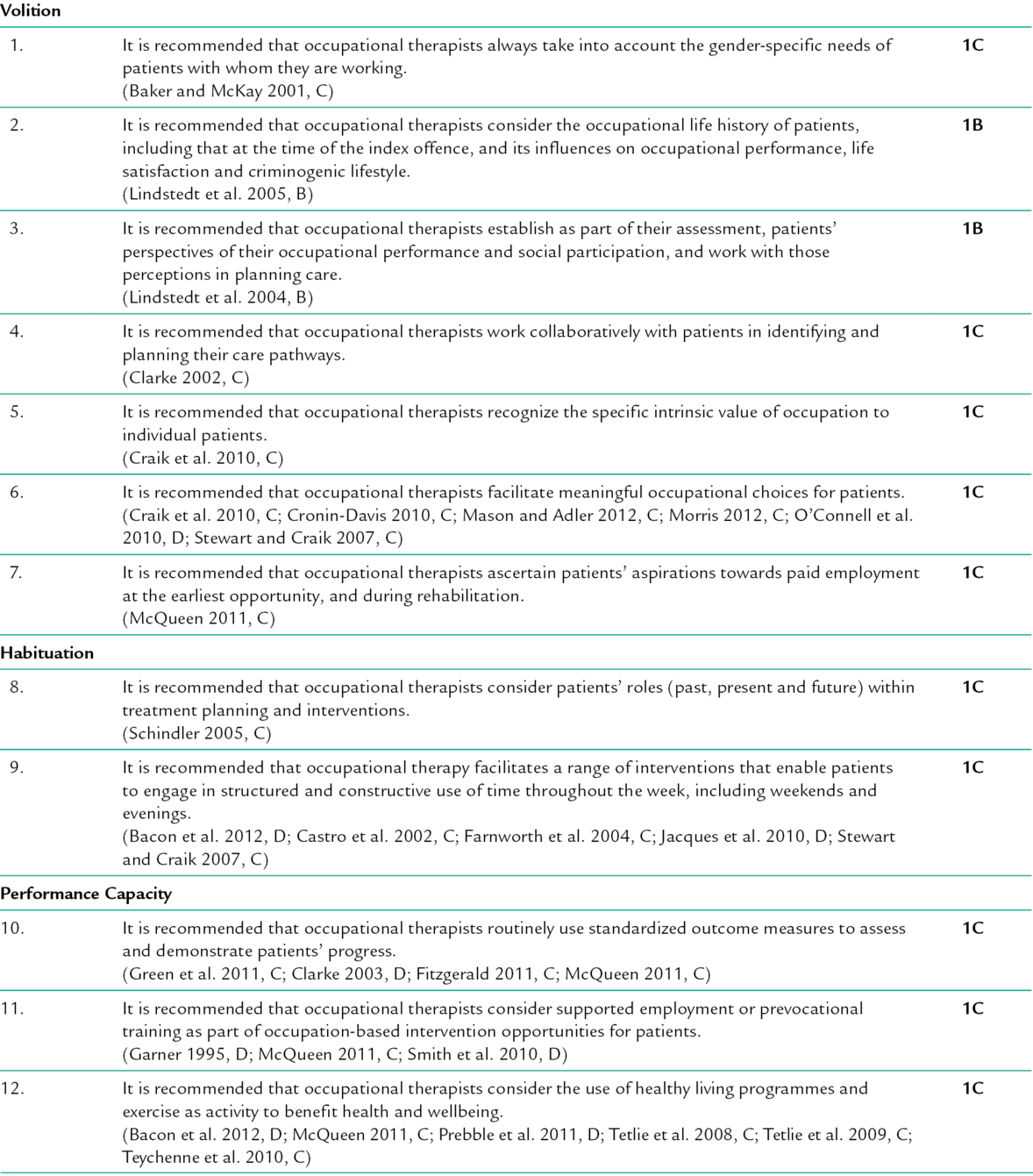

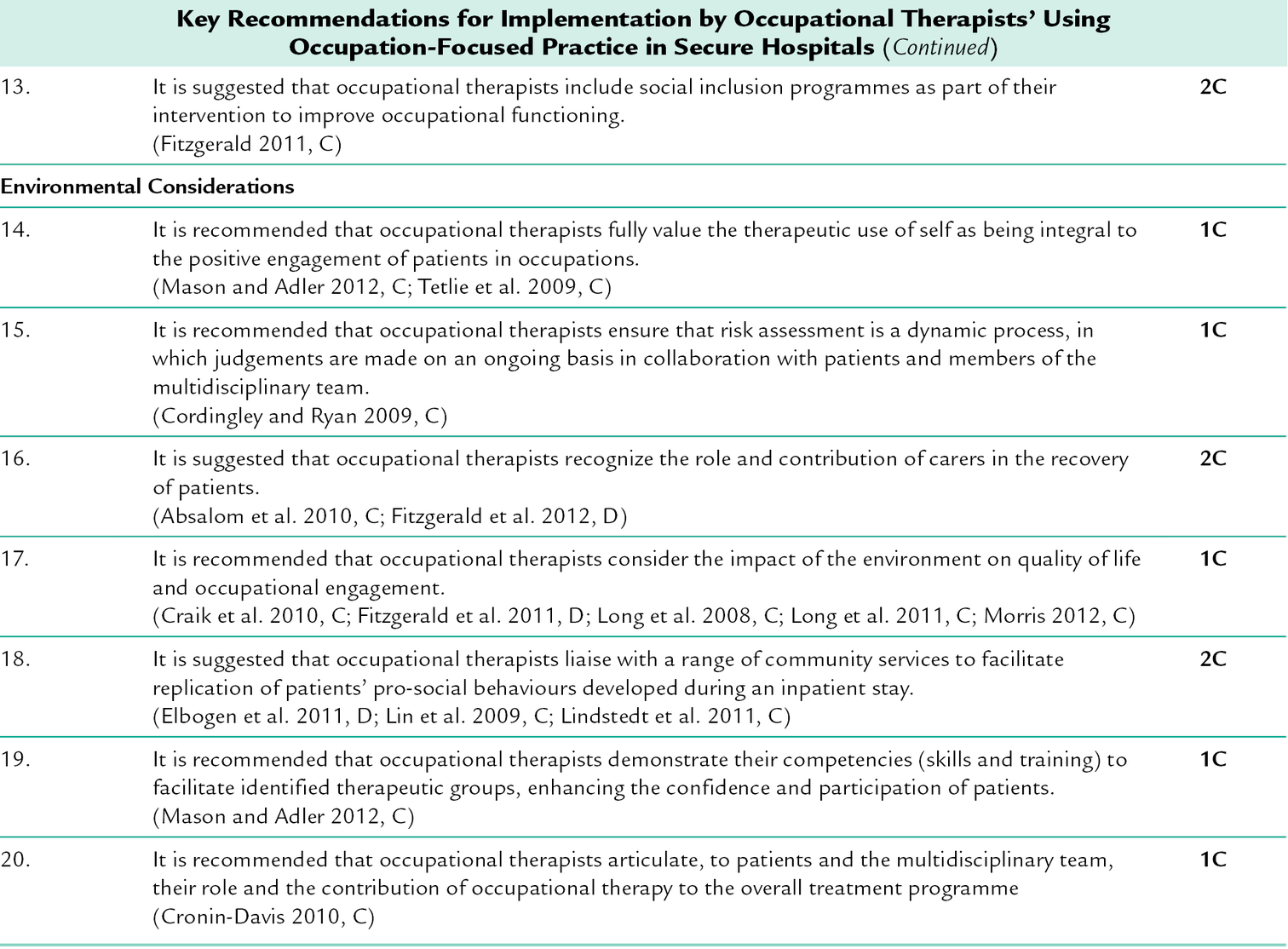

27 Sharon McNeill; Katrina Bannigan CHAPTER CONTENTS What are Forensic and Prison Services? Why are Forensic and Prison Services Needed? THE SETTINGS FOR FORENSIC MENTAL SERVICES Referral to Forensic and Prison Services Regional Secure Hospitals (Medium-Secure) Special Hospitals (High-Security Hospitals) Dangerous and Severe Personality Disorder (DSPD) Units Occupational Therapy Interventions Occupational Therapists’ Use of Occupation-Focused Practice in Secure Hospitals Black and Minority Ethnic Groups Offence-Specific Interventions CHALLENGES ASSOCIATED WITH WORKING IN FORENSIC AND PRISON SERVICES This chapter describes occupational therapy in forensic and prison services, considering risk assessment and team working. Offence-specific interventions will be explored. The chapter ends with a consideration of the challenges occupational therapists face in delivering occupational therapy within forensic and prison services. Criminal justice systems vary across the world; the system in England and Wales is used as an example because it is the system the authors are familiar with. Anyone working with people with mental health problems in other criminal justice systems across the world will need to take account of the legalities and procedures within the system they are working. For example in the USA, the different states that constitute the USA all have different mental health laws; South Africa has the Mental Health Care Act 2002 and in Japan, there is the Act on Mental Health and Welfare for the Mentally Disabled. Forensic mental health services have evolved over a period of 200 years to accommodate people who had committed an offence but were deemed insane and so not responsible for their actions (Duncan 2008). As a result of cases such as James Hadfield and Daniel McNaughton, legislation was passed to allow the incarceration of mentally disordered offenders and services developed to ensure that the places of incarceration were both therapeutic and secure (Duncan 2008). The term forensic is defined as ‘relating to or denoting the application of scientific methods and techniques to the investigation of crime or relating to courts of law’ (Soanes 2008). This should not be confused with forensic science, which is about establishment of scientific evidence for courts. Within health and social care, the term forensic is used to refer to working with individuals who are involved with a court of law or criminal justice system, or who are at risk of becoming so, and also have a mental health condition that precludes incarceration in a mainstream prison. It is not safe for these individuals to be admitted to an open ward, so they need to be treated in secure environments. The level of security they require depends on the danger they present to themselves and others (Rutherford and Duggan 2007). A key difference between mainstream mental health services and forensic mental health services is that the offending behaviour which brought the person into the criminal justice system is addressed, as well as their mental health problem(s). For example a man charged with serious assault might have problems with antisocial behaviour, such as violence and aggression, arising from impaired mental health associated with a diagnosis of schizophrenia. His care plan would include medication to ameliorate symptoms of psychosis, such as hallucinations or delusions. It would also include interventions to address his antisocial behaviours, requiring him to engage with social skills development or anger management. In the UK, the Reed report (Department of Health and Home Office 1992) was a catalyst for reforming of the criminal justice system so that mentally disordered offenders were diverted away from mainstream prisons in order to improve their care and rehabilitation. A sizeable proportion of men and women in prison experience two or more mental health disorders (Ministry of Justice 2009) and prisons are not effective in treating the causes of offending behaviour. The risk to the community posed by many individuals with mental health problems or learning disabilities is outweighed by the risk to them of exploitation by other prisoners. More recently, a ‘care not custody’ campaign in the UK has led to a national liaison and diversion service for vulnerable offenders to be developed and evaluated. There are a variety of offences that bring an individual into contact with the criminal justice system: aggression and violence; theft; arson; stalking; harassment; murder; attempted murder; manslaughter or sexual offences, which can include offences towards children, adults or sexual exposure. The services that an individual might receive, and the settings they may eventually be admitted to, depend upon the nature of the offence; for example serious offences would mean that an individual would be admitted to a high-security environment. In some cases, individuals may not have been arrested or charged with an offence, but there is a serious risk of offending, and local services such as mental health teams, police or social services, may have information which suggests the likelihood of offending is significant enough for an individual to require input from a forensic team; this may be community-based. Occupational therapy is the term used in this chapter rather than forensic occupational therapy, which has been used in previous editions of this text. Forensic settings can make occupational therapy practice more challenging because of the stringent security procedures and legal requirements. However, beyond this, the focus of occupational therapy is no different to other mental health settings. There is a need to avoid additional stigmatization of people in forensic and prison services, who experience the double stigma of being labelled as both mentally ill and a criminal (Thornicroft 2006). The stigma and discrimination faced by many are commonly described as being worse than the direct experience of mental health problems. Media coverage of high-profile cases may make it hard for the general public to understand that many people who have been in contact with forensic and prison services no longer present a danger to themselves or others (Thornicroft 2006). The consequences are that some women entering the prison system will choose not to disclose mental health problems through fear of being stigmatized or being perceived as different (NACRO 2009). It is important that occupational therapists not only avoid exacerbating the stigma, and the attendant discrimination, but work actively to reduce both. Occupational therapists work in a range of forensic settings (Duncan et al. 2003; Craik et al. 2010), including prisons, secure units and with specialities such as personality disorder services (see Ch. 23) or learning disabilities (see Ch. 26). In England and Wales, there are a number of different secure services for the mentally disordered offender; including low secure units, regional secure units, special hospitals, dangerous and severe personality disorder (DSPD) units and prisons. The nature of their services and security vary depending upon who they serve and the levels of risk the individuals pose both to themselves and to others. As the levels of security and risk vary, so does the work the occupational therapist can do within the setting. Tensions can exist between providing the right levels of security for safety and creating an environment conducive to care and treatment. Occupational therapists working in this field need to familiarize themselves with the language of the criminal justice system, for example criminogenic lifestyle; index offence; offending behaviour; public protection; resettlement and security; as well as developing a detailed understanding of the legal framework they will have to practice in. The legal context shapes intervention planning, so that any activity planned does not contravene any legal restrictions. For example, a person may not be allowed, due to a legal restriction from the ministry for justice, to go to certain places such as parks or shopping centres. Referral criteria for forensic and prison services include details of the mental disorder (usually identified prior to referral by prison teams or diversion teams) and offending history or risk of offending. Referring agencies include: ■ Community learning disability teams, community mental health teams, crisis teams ■ The criminal justice system including the courts, the probation service, the prison service, Crown Prosecution Service and solicitors ■ Multi Agency Public Protection Arrangements ■ Social Services departments ■ Child and adolescent services ■ Youth offending teams. Many services have assessment teams which include psychiatrists, nurses, occupational therapists, psychologists and social workers. Prior to a referral being accepted, assessment is conducted by the team. Often it can be difficult to clearly identify a person’s true presentation and a period of further assessment will be required. Assessment involves information gathering from the individual and their family/support networks as well as from those who are currently providing care and/or support. An effective team approach to assessment will use the team member’s specialist professional skills and knowledge, to map out the individual’s life and identify what has led to the offences. A formulation will enable the team to identify possible outcomes of treatment pathways. Then a decision will be made about whether to accept the referral. This process may vary in different teams and settings. Low-secure units can be found within mental health hospital settings or within communities. The individuals who reside within these units may have progressed from medium-secure services and be working towards community reintegration, or they may have come directly from the community or prison services. The low-secure unit will tend to admit individuals who pose a lesser risk to others. The nature of the offences committed does not tend to include serious crimes such as murder. The low-secure unit will still operate security and have locked doors, with levels of restrictions on items allowed such as lighters, sharp items such as razors, and movement between wards/units will still be restricted. Many low-secure units, e.g. PICU, will operate the same environmental levels of security as medium-secure units. However, in low-secure services there may be more movement in and out of the unit, with people having greater community access. This will be escorted or unescorted, depending on a person’s level of risk. The function of a medium-secure unit is to provide a step down in levels of security from a high-secure setting and provide further access to assessment, treatment and interventions for people who are able to move towards rehabilitation and community integration. In some instances, they will move directly from low-secure services to medium-secure provision, when there is an increase in risk behaviours that cannot be managed within the provision of the low secure service. In other instances, they may be directly admitted to medium-secure provision from prison or from court. The majority of referrals will come from prisons and other secure services. Where referrals come from the prison, a psychiatrist within the prison will have already completed an assessment and a team from the secure service will then complete further assessments to determine the suitability of the secure environment. The medium-secure or regional secure unit operates a high level of relational security (see Box 27-1), where people are observed closely, their movement around the units is restricted by a number of locked doors and access to therapy areas may have to be escorted. To begin with unescorted leave will not be granted in a medium-secure unit. Daily security checks are carried out by the unit staff. These include: ■ Perimeter checks, making sure all windows and doors are not tampered with ■ Cutlery counts each meal time, as well as counting kitchen items, including pots and pans ■ Entrance and exit checks, making sure that all the doors lock correctly ■ Kitchen safety including counting the sharp knives and scissors (usually kept in a locked safe) ■ The nurse in charge will count any monies held on the unit in the safe ■ Newspapers and magazines will be checked and any content deemed inappropriate will be removed ■ Random checks may be carried out to check for any contraband items in bedrooms ■ Daily communal areas checks including the courtyards, lounges and any quiet areas. Other methods are used subtly within the environment to aid safety and security; for example furniture within communal areas may look like regular furniture but be weighted so that it cannot be lifted easily, moved or thrown. Similarly, in the bedrooms, the furniture is fixed to the floor. In many modern units, the fixed furniture has been carefully designed to provide safety and security, while looking homely and comfortable. Many units are designed to have minimal blind spots to make observation easier; in some units, this is achieved using CCTV (closed circuit television). To maintain privacy and dignity, the use of CCTV is usually only in corridors or communal areas and not in bedrooms. Many medium-secure settings will have designated occupational therapy centres, where the occupational therapist can use activity as a therapeutic tool to enable occupational engagement, promoting choice, developing skills, increasing motivation and working with the individual to realize their potential. Activities may include art and craft, music, computers, wood work, animal care, gardening, adult education, social groups and sports/gym. Security and risk will feature highly in the occupational therapist’s intervention planning: items such as knifes, scissors, needles and tools are all required to be counted before and after a person enters or leaves an area. Special hospitals, as part of a continuum of mental health provision, provide a therapeutic environment within a maximum-security setting for those people who are deemed dangerous and of sufficient risk to themselves and others to require the high-security setting (Walsh and Ayres 2003). While special hospitals may look like a prison from the outside, inside treatment takes place within a therapeutic environment, focusing on increasing social interaction to avoid withdrawal as well as skills development, through the use of art, education, vocation and social activities. In the UK, they are part of the National Health Service. Some special hospitals, such as Rampton in England, provide discrete services including: ■ Specialist high-secure women’s services ■ High-secure learning disability services for the whole of England ■ A Dangerous and Severe Personality Disorder (DSPD) unit ■ National high-secure deaf service, which provides comprehensive multidisciplinary team assessment, treatment and rehabilitation for up to 10 deaf people, irrespective of their diagnosis or treatment pathway. The average stay is 6.5 years before progressing to a medium-secure unit. These units were established to treat violent and sexual offenders that otherwise would be deemed untreatable and to promote public protection (Ministry of Justice and Department of Health 2008). The term DSPD is an administrative rather than medical label, which is applied to people who: 2. Have a severe disorder of personality and a link can be demonstrated between the disorder and the risk of reoffending (Ministry of Justice and Department of Health 2008). DSPD units are designed to deliver mental health services for people who are or have previously been considered dangerous as a result of severe personality disorder (Home Office 1999). The main objectives of the programme are: ■ Provision of new treatment services improving mental health outcomes and reducing risk ■ Understanding what works in treatment and management of those who meet DSPD criteria. The main philosophy of the DSPD programme is that public protection will be best met by addressing the mental health needs of a previously neglected group. There are a vast number of prisons in England and Wales. Each prison is usually divided into two types of provision for men and women separately; remand and sentence serving. Those on remand are housed within the remand section of the prison, usually a separate block or wing and they are able to have frequent visitors and wear their own clothes, however if convicted, they are then moved to a part of the prison that reflects the nature of their crime (Rogowski 2002), i.e. Category A prisoners are those whose crimes are serious and they require high levels of security, such as terrorists. Other categories go down towards category D, which are open prisons, where the inmate will have some level of day release, for example to a work placement. Healthcare in prison is often delivered within a certain part of the prison and, similar to a health centre, it is run by healthcare professionals, either employed by the government as part of the penal system healthcare provision or by health services. In the UK, there have been a number of developments in the provision of healthcare services within prisons over the last decade; the aim is to have on offer a service to inmates that is equal to that they would receive as members of the wider community (Hills 2003). Within the prison setting, mental health issues are common; 10% of men and 30% of women have had previous psychiatric admission before they entered prison. Women prisoners account for 54% of self-harm incidents. Male prisoners, with experience of psychosis, are more than twice as likely to spend 23 or more hours a day in their cell than those without mental health problems (Prison Reform Trust 2010). The proportion of people in prison who have learning disabilities or learning difficulties that interfere with their ability to cope with the criminal justice system has been estimated at 20–30% (Ministry of Justice 2009). The effects of being incarcerated or detained within prisons is well recognized; the fact that the environment and regimes are designed so that a person’s ability to make choices is taken from them is intentional. Hills (2003) stated that the restricted and institutionalized nature of prison life is intended but it impacts on occupational choice and balance, contributing to mental health problems. Healthcare teams based in prisons have to be skilled in recognizing the impact of the environment, taking into account the social environment for prisoners may involve bullying, harassment and even exploitative relationships (Garboden 2011). The professionals within the prison service work closely with other secure services so if, for example, an inmate is displaying signs of an emerging mental ill health, they will refer them to the regional secure unit for further assessment and similarly, where an inmate may potentially be within the learning disabilities range, they can refer to the learning disability forensic service for further assessment. Where individuals have mental health problems at the time of their arrest, or of sentencing, the courts will refer them directly to mental health or learning disability forensic services for assessment before they are prosecuted. If the services find that the individual does not have a learning disability or does not require the regional secure unit provision, they may be returned to prison and in some cases, if an individual has been through a learning disability forensic service and completed various treatment pathways and reoffends, the courts will automatically opt for a prison sentence, though the service will still remain closely involved. Whatever area of forensic and prison services occupational therapists work within, they will face the same challenges of balancing risk management with creating a therapeutic environment. Occupational therapists have to follow strict protocols for risk and safety for themselves and others; movement between areas is restricted and community presence is unlikely. It is important that occupational therapists maintain a person-centred approach with individuals but within the constraints of the environment. Working in secure settings requires the occupational therapist to consider risk in every intervention and interaction as some people pose a greater risk than others; for example those who are acutely unwell or those who have been newly admitted and where little is known about their history and risk factors. Responsibility for safety lies with the occupational therapist who should consult relevant records prior to meeting a person, to be aware of known risks. They must communicate with the unit or ward staff before any session, to be sure it is safe to meet with the person. Adequate steps to ensure personal safety should be taken, for example, having a member of staff present or conducting a session in a place where others are present. Most units will operate an alarm system, which requires the occupational therapist to carry an alarm on entering the environment. When the alarm is activated, a response team attends to the alarm call. As a team member, occupational therapists participate in risk assessment. Basic principles include exploring risk factors in relation to the individual and others. Current and past history will be considered, to inform a risk management plan. The documents for risk assessment and management will vary from setting to setting. Services may use specific risk assessment tools such as the HCR-20 (historical, clinical, risk management) or use a tool developed by the service – although it is suggested that tools based on intuition and clinical experience alone are not sufficiently reliable in assessing risk (Ho et al. 2009). Risk assessment has become an integral part of the management of the mentally disordered offender (Ho et al. 2009) and should be seen as dynamic and ever-changing. Risk assessment principles should be adhered to throughout the occupational therapy process. Cordingley and Ryan (2009) suggest that there is no specific model for occupational therapy risk assessment. For example, while facilitating a group, the occupational therapist needs to consider the mix of group members, by questioning whether certain individuals will provoke others, and considering if some individuals are likely to be vulnerable if mixed with others. Cordingley and Ryan (2009) suggest that risk can be mapped for occupational therapists by using the concepts of the Person, Environment, Occupation and Performance Model. O’Connell and Farnworth (2007) highlighted that, for occupational therapists, no clear rationale has been offered as to why a separate risk assessment would be needed from the risk assessment completed by the team. However, many occupational therapists choose to have a separate assessment that is cross-referenced to the team risk assessment. Additional details relate to the specific risks involved in activities such as cooking or in places such as an occupational therapy workshop. Inventories are often used for items such as scissors, needles and knives. There may also be restrictions on the types of glue used or the availability of sticking tape. Assessment by the team should consider potential risks to the individual and to others, including those associated with a physical impairment or limitation, which may increase the likelihood of accidental self-injury. However, it is important to recognise that activities do not have to be restricted if a person poses a risk. For example, if they are at risk of self-harming and cannot access a kitchen for a cooking session, the occupational therapist can grade the activity so that the individual takes part in cold food preparation in the ward environment such as a salad or baking. The occupational therapist can put the dish prepared by the individual into the oven so the person does not have to access the kitchen. Within any health and social care setting, team working is an important factor influencing the quality of therapy and care. Within the forensic setting, communication is necessary to ensure the effective management of risk. According to Partridge et al. (2010, p. 69) a ‘well-functioning team is stronger than the sum of its parts’. This means if a team has a good understanding of each profession’s roles, skills, and professional ethos and the team shared the same direction, then the team as a whole is more likely to be effective than an individual professional. Team members need to feel confident in their own abilities. First, occupational therapists need to be clear about their role, approach to intervention and direction that they are taking. Communicating this effectively with the team is important, rather than making assumptions that other professions have the same shared understanding. Equally, it is important that the occupational therapist is clear about what is not within the professional remit. In forensic and prison services, many occupational therapists find themselves working as lone professionals within teams, so it is important to make sure that occupational therapists do not feel pressurized into practice that is beyond their scope of practice. This can be quite difficult: what is needed is good support from a manager, as well as good clinical supervision from an occupational therapist which may have to be arranged with an external person. Occupational therapists use their skills in analysing and adapting environments to enable people to engage in therapy in order to maintain motivation. This can be achieved by promoting choice, supporting skills development and working with individuals towards short-term and long-term goals. Skills development may focus on: ■ Budgeting, cooking and independent living skills ■ Communication and assertiveness ■ Drug and alcohol awareness ■ Literacy and education ■ Motivation ■ Relationship development ■ Social skills ■ Vocational and skills development (see Ch. 21). This may be done within the ward environment, at an activity (or resource) centre or in the community. Some occupational therapists find the restricted environment a major barrier and the regime of the unit too institutionalized, meaning that choice making and promoting independence can be difficult (O’Brien and Bannigan 2008). For example, prisons operate differently from hospitals. The daily regime will follow a routine of lock down, where isolation is imposed; this can be difficult for the occupational therapist who is attempting to engage the people in activities. The occupational therapist will have to work carefully with prison officers to promote positive occupational engagement for the inmates. It is the role of the occupational therapist to advocate for the individual and to find ways to support the ward/unit to be able to make individualized plans which allow for skills’ development and goal attainment and not just security and risk management. The approach to occupational therapy is the same in forensic and prison services as it is within non-secure environments (see Chs 22, 23 and 26). However, many occupational therapists within secure settings will adopt a dual perspective to their interventions by considering: ■ How does the individual’s offence and environment affect their ability to function independently? Martin (2003) observed that some theories of practice are overly complex and can make straightforward interventions seem complicated. The occupational therapist in the secure setting breaks down interventions into their component parts, so that everyone understands the processes and the reasons the approach used. Within occupational therapy in forensic practice, the Model of Human Occupation (MOHO) continues to be the most commonly used model of practice (O’Connell and Farnworth 2007; Bennett and Manners 2012; COT 2012). MOHO is regarded as a useful model of conceptual practice; this may be due to its evidence base and having a forensic-specific assessment tool (Couldrick and Alred 2003; O’Connell and Farnworth 2007; Duncan 2008). The Occupational Circumstances Assessment Interview Rating Scale (OCAIRS) includes three interview subsections, one of which is a forensic mental health interview tool (Model of Human Occupation 2012). The tool aims to provide a structure for gathering, analysing and reporting information relating to an individual’s occupational participation. The three main domains of OCAIRS are: ■ Roles: family responsibilities, family contact, study, culture and religion ■ Habits: daily routine patterns, sleep, previous routine patterns, satisfaction with routines ■ Personal causation: understanding own abilities, what do they feel they do well at, what are they proud of, how successful they feel they are going to be. The assessment provides insight into an individual’s level of motivation and how empowered they feel to be an active participant in their treatment pathways. Occupational therapists adjust and adapt the questions when administering the tool. OCAIRS is one of a number of different assessment tools used by occupational therapists in forensic and prison services; some are occupational therapy specific and others are generic and focus on entities such as mood or self-esteem. The process of assessment, treatment and evaluation utilized by occupational therapists within forensic settings is iterative and will involve working with the person on a range of areas or needs (see Chs 5 and 6, for a broader discussion of assessment and outcome measurement and intervention planning, respectively). A review of occupation-focused practice in secure hospitals formed the basis for recent practice guidelines, which were structured using four concepts associated with the Model of Human Occupation (Kielhofner 2004; COT 2012). Table 27-1 indicates the key recommendations. The guidelines indicate that individuals should be supported to engage in meaningful and valued occupations, to limit alienation and antisocial behaviour and connect people to society again (Couldrick and Alred 2003). (See Case study 27-1 for an example of occupational therapy in a secure setting.) TABLE 27-1 Key Recommendations for Implementation by Occupational Therapists’ Using Occupation-Focused Practice in Secure Hospitals From the College of Occupational Therapists, 2012, Occupational therapists’ use of occupational-focused practice in secure hospitals: practical guideline, published by the College of Occupational Therapists, www.cot.org.uk. Reprinted with kind permission. Key: Recommendations are scored according to strength, 1 (strong) or 2 (conditional), and graded from A (high) to D (very low) to indicate the quality of the evidence.

Forensic and Prison Services

INTRODUCTION

What are Forensic and Prison Services?

Why are Forensic and Prison Services Needed?

Labelling and Stigma

THE SETTINGS FOR FORENSIC MENTAL SERVICES

Referral to Forensic and Prison Services

Low-Secure Units

Regional Secure Hospitals (Medium-Secure)

Special Hospitals (High-Security Hospitals)

Dangerous and Severe Personality Disorder (DSPD) Units

Prison Services

WORKING IN SECURE SETTINGS

Risk Assessment

Team Working

Occupational Therapy Interventions

The Model of Human Occupation

Occupational Therapists’ Use of Occupation-Focused Practice in Secure Hospitals

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree