21 Forensic psychiatry

Crime and psychiatry

Aspects of criminology

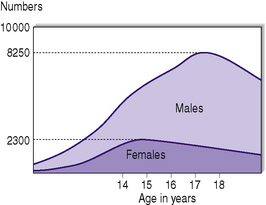

The peak age of offending in the UK is 14 years for girls and 17–18 years for boys (Figure 21.1). Studies in inner London have shown that up to one in five boys have at least one conviction by the age of 21. Half the indictable crimes (more serious and eligible for trial by jury) are committed by persons under the age of 21, and 30% of males have been convicted of such an offence by the age of 30. Crime, in general, decreases with age as personality matures, except for a small peak for women aged 40–50, around the menopause. With the falling numbers of those aged 14–15 in the UK, i.e. the peak age of committing crime, there has been a corresponding fall in the rates of certain offences.

Premenstrual tension and crime

Mens rea and UK forensic psychiatry hospital facilities

Juvenile delinquency

Aetiology

Individual developmental factors

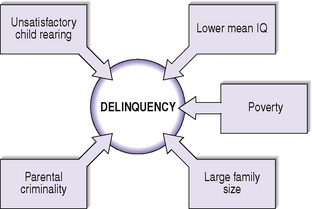

The factors summarized in Figure 21.2, if present, are associated with the development of delinquency. If three of these five factors are present, there is a 40% chance of the individual showing delinquent behaviour during adolescence. Also, if troublesomeness at school is noted there is a 50% chance of later showing delinquent behaviour.

Prognosis

More recently, a 32-year follow-up of a birth cohort of 1000 New Zealanders has differentiated, apart from adult onset offenders and discontinuous offenders, life course persistent offenders and adolescence limited offenders and the implications for treatment, which is shown in Table 21.1.

Table 21.1 Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health and Development Study 32-year follow-up of birth cohort of 1000 New Zealanders

| (A) Life course persistent offenders | |

| Rare, small numbers but responsible for half crime rate | |

| Neurodevelopment problems ↓ Temperament difficulties  ↓ Disruptive behaviour  ↓ Social learning poor  ↓ Personality disorder, particularly antisocial personality disorder which is present in 15–25% ↓ Serious violence | Disrupted attachments Ineffective discipline Delinquent peer influences, truanting, etc. |

| Victimisation of partners and children | |

| Poor physical, sexual and psychiatric health (especially depression) | |

| Substance dependence (opiates) and alcoholism | |

| More traumatic injuries | |

| Management | |

| Require early childhood interventions in family, but as a chronic cumulative condition requires lifelong interventions | |

| (B) Adolescent limited offenders | |

| Common | |

| Good neurodevelopment and also social and academic skills | |

| Maturation gap in period 15–25 years | |

| Extrovert, sensation seeking and risk taking | |

| Prognosis better if good partner and job | |

| Requires individual treatment, e.g. cognitive behavioural skills training during teen years to counteract peer influence (group treatments facilitate deviant peer networks) | |

| Parent management training and education useful | |

Mentally abnormal offenders

Forensic psychiatric assessments

Areas to be considered in a forensic psychiatric assessment are shown in Table 21.2.

Table 21.2 A forensic psychiatric assessment

Table 21.3 outlines areas to be covered in a clinical forensic psychiatric risk assessment and management plan.

Table 21.3 Clinical risk assessment and risk management planning

| The aim is to get an understanding of the risk from a detailed historical longitudinal overview, obtaining information not only from the patient, who may minimize his past history, but also from informants. Ideally it should not be a ‘one-off’ single interview assessment. |

| Reconstruct in detail what happened at time of offence or behaviour causing concern |

| Independent information from statements of victims or witnesses or police records should be obtained where available. Don’t rely on what the offender tells you or the legal offence category, e.g. arson may be of wastepaper bin in a busy ward, or with intent to kill. Possession of an offensive weapon may have been prelude to homicide. |

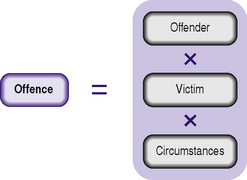

| N.B. Offence = offender × victim × circumstances. |

| RISK FACTORS FOR VIOLENCE |

| Demographic factors |

| Male |

| Young age |

| Socially disadvantaged neighbourhoods |

| Lack of social support |

| Employment problems |

| Criminal peer group |

| Background history |

| Childhood maltreatment |

| History of violence |

| First violent at young age |

| History of childhood conduct disorder |

| History of non-violent criminality |

| Clinical history |

| Psychopathy |

| Substance abuse |

| Personality disorder |

| Schizophrenia |

| Executive dysfunction |

| Non-compliance with treatment |

| Psychological and psychosocial factors |

| Anger |

| Impulsivity |

| Suspiciousness |

| Morbid jealousy |

| Criminal/violent attitudes |

| Command hallucinations |

| Lack of insight |

| Current ‘context’ |

| Threats of violence |

| Interpersonal discord/instability |

| Availability of weapons |

| Consider also protective factors |

| Practical risk assessment (history × mental state × environment) can be supplemented by standardized instruments of risk, including actuarial risk instruments based on static risk factors, e.g. Violence Risk Appraisal Guide (VRAG), and dynamic risk instruments, e.g. HCR-20 (historic, clinical and risk management -20), based on factors that can change or be managed, e.g. symptoms of mental illness and non-compliance. The psychopathy checklist-revised (PCL-R) was devised by Hare and is used to measure the presence and level of psychopathy, and has been proven to be a good predictor of risk. A short version (PCL-SV) can be used in non-forensic populations. The psychopathy checklist has two main factors (personality traits and deviancy of social behaviour). Only one-third of antisocial personality disorders reach checklist criteria for psychopathy on this scale. |

| In conclusion |

| Aim to answer how serious is the risk, i.e. its nature and magnitude, is it specific or general, conditional or unconditional, immediate, long term or volatile. Have the individuals or situational risk factors changed? Who might be at risk? |

| From such a risk assessment, a risk management plan should be developed to modify the risk factors and specify response triggers. This should ideally be agreed with the individual. Is there a need for more frequent follow-up appointments, an urgent care programme approach meeting or admission to hospital, detention under Mental Health Act, physical security, increased observation and/or medication required. If the optimum plan cannot be undertaken, reasons for this should be documented and a back-up plan specified. |

| Risk assessments and risk management plans should be communicated to others on a ‘need to know’ basis. On occasions, patient confidentiality will need to be breached if there is immediate grave danger to others. Police can often do little unless a specific threat is issued to an individual, whereupon they may warn or charge a subject. Very careful consideration needs to be given before informing potential victims to avoid unnecessary anxiety. Their safety is often best ensured by management of those at risk. |

Multifactorial nature of offending

When assessing an offender it is important to bear in mind that no psychiatric disorder is specifically characterized by offending, and it is important to see an offence as being due to a combination of the offender, the victim and the situation/environment (Figure 21.3).

Outcomes of sentencing

These are given in Table 21.4. In England and Wales an individual charged with an imprisonable offence may be detained in a psychiatric hospital under Section 37 of the Mental Health Act 1983 (a six-month renewable treatment order). A Section 41 Restriction Order may be added by a Crown Court. This requires Ministry of Justice authorization for leave, transfer or conditional or absolute discharge of the individual from hospital, i.e. it removes the final decision from the patient’s consultant psychiatrist and responsible clinician. The order is made ‘to protect the public from serious harm’ and allows for conditional discharge subject to conditions such as place of residence and compliance with psychiatric treatment.

Table 21.4 Outcome of sentencing of mentally abnormal offenders

• Community Rehabilitation (old Probation) Order, with or without condition of psychiatric treatment |

Association of particular mental disorders with offending

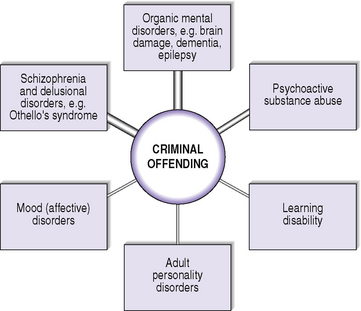

Remember offending is not a primary characteristic of any mental disorder and when considering an offence, consider not only the offender but also the victim and the circumstances. However, nearly all mental disorders may sometimes be associated with criminal offending (Figure 21.4).

Organic mental disorders

Huntington’s disease may present in the early stages with psychopathic behaviour.

The association of epilepsy with offending will be discussed in detail later.

Learning disabilities (mental retardation)

Mental abnormality as a defence in court

Risk assessment, dangerousness and risk management

Criminal responsibility

It is questionable how good psychiatrists are in judging responsibility, as opposed to diagnosing mental disorder.

Mental abnormality as a defence in court

In certain uncommon cases the offender offers evidence of his mental disturbance either:

Thus, in these cases the psychiatric evidence is presented as part of the arguments to the court and is heard before conviction.

Criminal Procedure (Insanity and Unfitness to Plead) Act 1991

(a) Unfit to plead

N.B. The defendant does not have to be fit to give evidence himself. There are current proposals to make this a more specific decision making capacity-based defence i.e. dependent on the ability to understand, remember and use relevant information to make, and to be able to tell their lawyer, their decisions.

(b) Not guilty by reason of insanity (‘special verdict’) (insanity defence) (McNaughton rules)

Technically, this plea may be put forward for any offence, but in practice it is usually only put forward for murder or other serious offences. In fact, such a plea is rare.

Homicide by mentally disordered offenders in England and Wales

Legal classification in England and Wales

Homicide may be lawful or unlawful.

Lawful homicide

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree