(1)

Department of Otorhinolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery, Asklepios Clinic Harburg, Eissendorfer Pferdeweg 52, 21075 Hamburg, Germany

Abstract

Treatment options for SDB are either conservative, apparative, or surgical. The decision regarding which treatment fits for which patients depends on several parameters. The most important criteria are severity of SDB, daytime symptoms, comorbidities, age (especially children or adults), BMI, site(s) of obstruction, and of course, the preferences of the patient. Today, guidelines, statements, and reviews that summarize scientific data according to evidence-based medicine criteria are available. This book highlights the data for each chapter according to the Oxford Criteria of EBM. Focussing on surgical treatment, the authors define five main areas of indication for surgery for SDB. These are (a) improvement of nasal breathing to support ventilation therapy (nasally applied CPAP), (b) minimally-invasive surgery for primary snoring and (very) mild OSA, (c) invasive surgery for mild and moderate OSA, (d) multilevel surgery for moderate and severe OSA as secondary treatment after failure or definitive interruption of ventilation therapy, and (e) adenotonsillectomy or adenotonsillotomie in pediatric OSA.

Core Features

Treatment options for SDB are either conservative, apparative, or surgical.

The decision regarding which treatment fits for which patients depends on several parameters. The most important criteria are severity of SDB, daytime symptoms, comorbidities, age (especially children or adults), BMI, site(s) of obstruction, and of course, the preferences of the patient.

Today, guidelines, statements, and reviews that summarize scientific data according to evidence-based medicine criteria are available. This book highlights the data for each chapter according to the Oxford Criteria of EBM.

Focussing on surgical treatment, the authors define five main areas of indication for surgery for SDB. These are (a) improvement of nasal breathing to support ventilation therapy (nasally applied CPAP), (b) minimally-invasive surgery for primary snoring and (very) mild OSA, (c) invasive surgery for mild and moderate OSA, (d) multilevel surgery for moderate and severe OSA as secondary treatment after failure or definitive interruption of ventilation therapy, and (e) adenotonsillectomy or adenotonsillotomie in pediatric OSA.

In the meantime, a multitude of treatment options for SDB exists. They can be classified into conservative, apparative, and surgical methods. While this book focuses solely on surgical therapies, for the competent surgeon, it is necessary to be familiar with the conservative and apparative treatment options in order to be able to define the ideal therapy concept for every patient. What follows is, therefore, a concise discussion of the most important nonsurgical treatment options. We point the interested reader to readable surveys of the topic. Even when aware of the complete array of treatment options, the decision regarding which treatment is the best for which patient is not always easy. For years, the authors have been leading clinical seminars on this topic in the context of the German Academy for Otolaryngology, Head and Neck Surgery. The experiences from these courses are presented in the second part of this chapter.

2.1 Conservative Treatment

Conservative methods include weight reduction, optimizing of sleeping hygiene, conditioning in respect of the avoidance of certain sleep positions, and drug treatments.

Obesity is considered the main risk factor for SDB. But most patients are not able to reduce their weight sufficiently and consistently [570]. Yet, even in those cases in which healing is initially achieved merely through weight reduction, a symptomatic SBD may occur again later even though the weight is kept on a low level. This fact may be interpreted as indicating that SDB is a multi-factored event, in which obesity plays a significant role in the pathogenesis of many patients. But in the case of obese patients, other factors also usually play a role, which, together with the adiposity, contribute to the development of OSA. Nevertheless, a weight reduction is of essential importance and simplifies every other OSA therapy; however, weight reduction in itself is only rarely able to resolve an OSA without further therapy.

A new field in the treatment of SDB is surgical weight reduction, the so-called bariatric surgery. Chapter g12 highlights this issue.

The maintenance of a certain level of sleeping hygiene (avoidance of alcohol and sedatives, reduction of nicotine and other noxious substances, observance of a regular sleep rhythm, etc.) is part of the standard recommendations in the treatment of SDB. Obviously, no controlled long-term studies exist relating to these measures.

In the case of positional OSA, apneas and hypopneas occur predominantly or solely only in supine position. In these cases, one should always consider the existence of a primarily retrolingual obstruction site. In supine position, the tongue, in accordance with gravity, falls backward because of the physiological muscle relaxation. As a result of the lower mass, this effect apparently plays a lesser role in the case of the soft palate. As minimal criterion for a positional OSA, it is necessary that the AHI in supine position is at least twice the value of the AHI in lateral position. Similarly, there are incidents of primary snoring wherein socially disruptive respiratory noises are only manifest in supine position.

In order to prevent supine position, the following methods have been used: verbal instructions, a “supine position alarm”, a ball sewed into the back of the pyjama, or a vest, or backpack. Backpack and vest reliably prevent supine position; verbal instructions are only successful in 48% of cases. On average, the AHI could be reduced by 55%. Unfortunately, no long-term results exist for these methods, yet there are several controlled studies. All in all, data of 69 patients exist. The average success rate lies at 75% [447]. In a randomized cross-over study [335], a significantly better AHI was found with CPAP than with the backpack; however, daytime sleepiness and productivity were identical with either treatment.

Avoidance of supine position makes sense in the case of positional sleep apnea. It can also help in optimizing the results of a ventilation therapy or a surgical treatment.

In 1998, a survey was published, which assessed the efficacy of 43 drugs in the treatment of SDB [273]. Yet currently, there is no drug that can be considered viable in the treatment of SDB. Similarly, a Cochrane review on the topic of drug treatment of OSA found that the existing data do not support the efficacy of medication for OSA [690]. Therefore, a drug therapy cannot be recommended.

2.2 Apparative Treatment

Apparative treatment options include respiratory treatment with continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) with its various modifications, oral appliances, and electrostimulation.

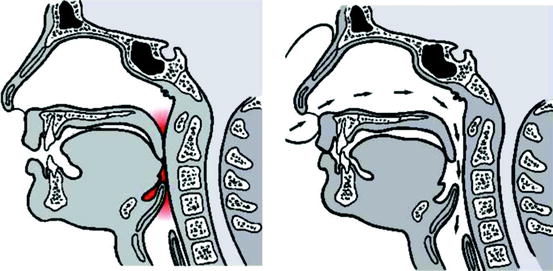

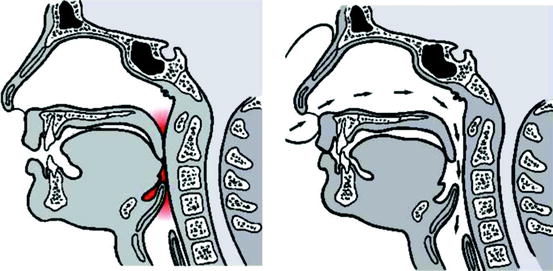

The CPAP ventilation therapy, according to Sullivan [728], which for the most part is nasally applied, splints the upper airway pneumatically from the nares to the larynx (Fig. 2.1).

Fig. 2.1

Method of pneumatic stenting of the upper airway with CPAP. (Left) Airway collapse. (Right) Stabilization with continuous positive airway pressure

Concerning the implementation of CPAP therapy and its diverse modifications, we refer to the specialized literature [158]. CPAP ventilation reduces or removes snoring, daytime symptoms, and the cardiovascular risk. Two excellent studies demonstrate the efficacy of the method [37, 330], as does a systematic Cochrane review [815]. With a primary success rate of 98%, CPAP therapy is, alongside tracheotomy, the most successful therapy modality available. Only these two treatment modalities achieve sufficient cure rates in cases of extreme obesity and severe OSA. With respect to quality of life and risk of traffic accidents, the cost effectiveness of a CPAP therapy was recently corroborated [29]. As an example of many new insights, we refer to the work of Drager et al. [162], which demonstrated that already after 4 months of CPAP therapy (compared to no therapy) significant changes of intima thickness, pulse wave speed, C-reactive protein, and catecholamines in the serum occured. A new review [258] demonstrates the efficacy of CPAP in comparison to placebo on arterial hypertonia under reference to 572 patients of 12 randomized studies.

Therefore, nasal CPAP therapy is considered to be the gold standard in the treatment of OSA. All other therapies for OSA must be measured against this method. Unfortunately, the long-term acceptance rate of CPAP therapy lies below 70% [453]. The acceptance rate of CPAP therapy especially decreases the younger the patient is, and the less his subjective ailments improve with a CPAP therapy [328, 416]. As a consequence, many patients with moderate and severe OSA in need of treatment have to be secondarily guided into another therapy. Often surgery is successful in these cases [699].

Among the oral devices, the mandibular advancement devices have established themselves. For mild to moderate severe OSA, success rates of 50-70% have been reported (new survey in [99]). The compatability of the mandibular advancement devices is given as between 40 and 80% [193]. Main side effects in up to 80% of the patients are hypersalivation, xerostomy, pain in the jaw, dental pain, and permanent teeth misalignments with malocclusion [542]. Oral devices are recommended for the treatment of simple snoring and mild and medium OSA.

Recently, the playing of digeridoos has been added as a curiosity to the list of OSA therapies. A first randomized study [583] demonstrates a significant effect on AHI and daytime sleepiness for 25 sleep apnea patients after 4 months of digeridoo playing in comparison to zero therapy. The playing of digeridoos allegedly strengthens the floor of the mouth and tongue muscles, comparable to electrical stimulation therapy. However, the latter has only been shown to have a limited effect on the AHI [588, 589, 779]; therefore, this form of therapy has not established itself as an isolated treatment option. As supplemental therapy, the strengthening of the muscles of the upper airway is certainly valuable.

2.3 Fundamental Reflections Regarding the Treatment Decision

If a patient is transferred for treatment of sleep disordered breathing (SDB), there are basically several factors that have to be taken into account to make a proper treatment decision (Table 2.1).

Table 2.1

Criteria for treatment decisions in sleep disordered breathing

Criteria for treatment decisions |

|---|

Adults or children? |

Daytime symptoms? |

Does the patient prefer surgical or nonsurgical treatment? |

Site(s) of obstruction |

Severity of disease (AHI, symptoms, concommitant diseases) |

Special shapes of OSA |

Only in supine position |

Complex malformations |

Laryngeal OSA |

2.3.1 Pediatric SDB

As stated in Chap. 1, the medical conditions vary substantially in children compared to adults. For children, already more than 2 breathing pauses per hour of sleep are considered pathologic. We refer here to an engaging current survey [261]. Since the sleep-medical anamnesis and diagnosis of children are much more difficult and elaborate, the question is which children should be examined more closely. Concerning this question, several new results exist, of which the following will be discussed as examples. The anamnesis in children can be supported with specific questionnaires. For instance, the Pediatric Sleep Questionnaire (22 items) was successfully used in a longitudinal study of 159 children before and 1 year after an adenotonsilectomy [108]. Other authors use their own questionnaires [478, 730]. In any case, obese children should be examined. Obesity and increase of the BMI are considered to be primary risk factors [839]; however, they also count as secondary risk factors for the recurrence of an OSA after an initially successful adenotonsilectomy [21]. Further risk factors for OSA are trisomy 21, tonsilhyperplasy, low social status, and low weight at birth [536, 672, 700, 838].

2.3.2 Daytime Symptoms

Most frequent symptoms of OSA are arhythmic snoring, unquite sleep, daytime sleepiness, and reduction of intellectual vigor. In contrast, the significantly higher risk of morbidity and mortality (in comparison with the healthy population) is not directly noticeable for a sleep apneic, but remains a hypothetical risk. For treatment success of an aid, for instance, nCPAP therapy or oral appliances, a consistent use of the aid is neccessary. Herein often lies the problem. Today, it is known that especially patients who initially experience a significant improvement of their daytime symptoms after starting the use of their aid show a high long-term compliance. In these cases, the subjective advantage (finally restorative sleep) stands in a good relation to potential inconveniences which the long-term use of these aids includes. On the other hand, it is often the patients who experience little subjective advantage from the therapy who will discontinue a genuinely effective therapy. Included in this group are of course those patients who already have experienced few or no daytime symptoms before the therapy. This group is particularly suited for surgical therapy since after the perioperative phase, a special therapy compliance is not needed.

2.3.3 Patient Expectations

Frequently, patients will already have had contact to self-help groups or friends and family, or have informed themselves through other means. Our daily practice has shown us that the patients often already come to a consultation with a specific therapy notion. Specifically, there are patients who do not want to undergo surgery under any circumstances;others do not want to use an intrusive appliance which they will have to use their whole life. In the framework of the therapy principles described here, we always attempt to take into account the wishes of the patients, unless serious reasons indicate that it is neccessary to counter a patient’s expectation. We have found that being aware of a patient’s wishes helps us in guiding our patients.

2.3.4 Site(s) of Obstruction

For CPAP therapy it is irrelevant where exactly the site(s) of obstruction is (are) located in the upper airway, because the whole upper airway is being pneumatically aligned. For the treatment decision for oral devices and especially for the customized surgical therapy, a thorough knowledge of the site(s) of obstruction is neccessary. The following Chap. 3 discusses the scope of topodiagnosis.

2.3.5 Severity of SDB

The severity of SDB is crucial in deciding which therapy is most suitable for which patient. The simple snorer is not ill. Therefore, the goal of treatment in the case of primary snoring lies in the reduction of both the duration and the intensity of snoring to a socially acceptable level. In principle, it needs to be kept in mind (1) that a treatment should not harm the patient, (2) that a treatment should only be carried out if the patient has explicitly articulated such a wish, and (3) that after any treatment, nasal ventilation therapy should remain possible [17]. This last aspect is of importance due to the fact that the incidence of OSA increases with age [427]. Many cases have been described in which nasal ventilation therapy was no longer possible due to the development of a nasopharyngeal insufficiency or stenosis [485], especially after aggressive soft palate surgery. These cases have in many places seriously impaired the trust in soft palate surgery.

In the case of OSA, the goal of treatment consists in a complete elimination of all apneas, hypopneas, desaturations, arousals, snoring, and other related symptoms in all body positions and all sleep stages. Of course, here it also has to be stressed that a treatment should in principle not harm the patient. But it must be pointed out that in the case of OSA, a disease with corresponding symptoms is already manifest. Therefore, in order to achieve the therapy goal, one will be less reluctant to consider a more invasive therapy with heightened morbidity and complication rate, a decision which would not be defensible in the case of harmless primary snoring.

In general, the severity of OSA is classified according to the apnea hypopnea index (AHI; equals the number of apneas plus the number of hypopneas per hour of sleep). Unfortunately, especially in the case of the mild forms of SDB, the AHI is not necessarily correlated to the clinical symptoms of the patients. Furthermore, the AHI is age-dependent. Concerning adults, the updated version of the International Classification of Sleep Disorders (ICSD) [12] uses the following distinction for OSA:

Mild OSA | 5 ≤ AHI < 20 |

Moderate OSA | 20 ≤ AHI < 40 |

Severe OSA | 40 ≤ AHI |

The term upper airway resistance syndrome (UARS) is subsumed under the diagnosis OSA because the pathophysilogy does not significantly differ from that of OSA. It needs to be taken into account that the above values are applicable to 30-year olds. In the case of a 70 year old, an AHI of maximally 15 is still not necessarily in need of treatment if the patient does not have any daytime symptoms.

Apart from the AHI, the ailments of the patient play a role. That is, a patient with a low AHI suffering from intense daytime sleepiness may already be in need of treatment, whereas an older patient with an AHI of 15 may be fine without treatment. The concommitant diagnoses also need to be taken into account. Since SDB constitutes risk factors for myocardial infarction, arterial hypertension, and strokes, patients with a corresponding anamnesis need to be sufficiently treated early on. One should also take special note of traffic accidents in the anamnesis, as these are frequently a result of sleepiness behind the wheel, which again suggests the existence of an SDB [121, 230, 268, 537].

In younger but not in middle-age groups, OSA has been reported to be more prevalent in African Americans compared with Caucasians. The prevalence of OSA in Asia patients with craniofacial features that predispose them to developing OSA may be high in spite of their having a BMI in comparison with Caucasian patients.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree