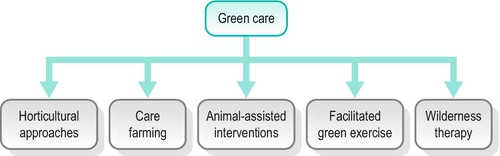

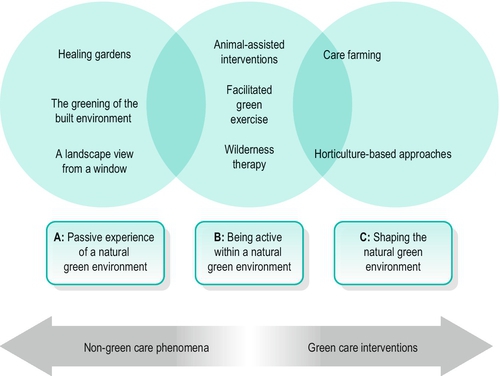

20 CHAPTER CONTENTS Green Care and Occupational Therapy GREEN CARE CONSTRUCTS AND THEORIES Psycho-Evolutionary Perspectives An Overload and Arousal Perspective The Human Relationship with the Natural World The Human Relationship with Plants and/or Animals GROUNDING GREEN CARE PRINCIPLES WITHIN OCCUPATIONAL THERAPY Occupational Science and Green Care Applying Occupational Therapy Models of Practice to Green Care Therapeutic Approaches Applicable in Green Care A Cognitive-Behavioural Approach THE GROWING EVIDENCE BASE FOR GREEN CARE The term green care describes a variety of health and social care interventions that intentionally harness nature in their approaches. The word green in this context, therefore, refers to using the natural green environment as a context for human occupation. It should not be confused with other uses such as in green politics or being environmentally friendly, for example; although there are overlaps as this chapter will show. There are many different types of green care intervention, including horticulture-based approaches, care farming animal assisted interventions, facilitated green exercise, and wilderness therapy (see Fig. 20-1); each of which has its own pedagogy, recognized practices and processes. FIGURE 20-1 An overview of the main intervention types comprising green care. In green care, nature is an integral component of an active intervention and not merely a pleasant backdrop to care (Haubenhofer et al. 2010; Sempik et al. 2010). This distinguishes green care from passive encounters with nature, such as when sitting in a garden, seeing a landscape view from a window or through the greening of the built environment. Furthermore, green care means designed, intentional, occupation-based therapeutic intervention, not just being active in natural settings. The distinction between certain nature-dependent phenomena that people experience as therapeutic and bona fide green care interventions is shown in Fig. 20-2. FIGURE 20-2 Nature-based phenomena and their association with green care. Green care provides many opportunities for occupational therapists to use the natural green environment and the occupations associated with it in their practice. Many of the principles, theories and frameworks used in green care are derived directly or indirectly from occupational therapy or have a bearing on it, and many occupational therapists use green care approaches within their practice (perhaps even being unaware that green care exists and that they are a part of it). Therefore, there is a need to provide theoretical knowledge to many green care practitioners who have an occupational therapy background. This chapter introduces specific green care interventions, describes their underpinning constructs and theories, grounds these within an occupational therapy framework to inspire practitioners’ professional reasoning, and highlights the growing evidence-base for green care. The reader is also directed to further resources to explore certain issues in more depth. Woven throughout the chapter are five illustrative case studies derived from practice. They show how green care operates within contrasting health and/or social care contexts: a forensic inpatient unit, a day service, a therapeutic community, a care farm and a vocational rehabilitation social enterprise. Like occupational therapy, green care is a complex intervention (Sempik et al. 2010); its efficacy is multidimensional and based on a synergy between the service user, the occupation they engage in, and the natural green environment. From an international perspective, there is no consensus on terminology for either the practice of horticulture-based green care or for its practitioners. These terms are all used: horticultural therapy, therapeutic horticulture, garden therapy, social and therapeutic horticulture. The latter term has emerged recently (particularly in the UK) to describe participation, by a range of vulnerable people, in groups and communities whose activities are centred on horticulture and gardening, but which differs from domestic gardening because it is formally structured as an intervention (Sempik and Spurgeon 2006). This shift in terminology highlights the importance of the social context. It emphasizes that the overall efficacy of the intervention comprises restorative processes arising from the natural, green environment and from the social milieu created through collective participation (Haubenhofer et al. 2010). It underlines the value of social and therapeutic horticulture as a route into the social capital of communities. In several countries voluntary professional registers exist or are being created in order to professionalize and assure the quality of practice (see Fieldhouse and Sempik 2007), with an associated regulation of job titles. Care farming (also known as social farming or green care farming) is the use of commercial farms and agricultural landscapes to promote mental and physical health through ordinary farming activities (Hine et al. 2008). The notion of multifunctionality has been adopted by many care farmers, whereby farms serve at least two different functions through their usual activities – that is, agricultural production and health/social care. While activities may be tailored to the abilities of participants, there is no separate facility on the farm for the provision of care. Care farms serve the needs of people with mental health problems, learning disabilities, addictions, dementia, and other challenges. There are different models, reflecting different national healthcare contexts (Haubenhofer et al. 2010). Animal-assisted therapy is a therapist-directed intervention evaluated in relation to specific therapeutic goals (Berget and Braastad 2008), while animal-assisted interventions refer to a more generalized approach using livestock, for example, within a care farming context (Kruger and Serpell 2006; Sempik et al. 2010). The rationale for these approaches is that caring for an animal, responding to its needs and learning to communicate with it develops psychological wellbeing and self-esteem. Animals show affection in response to the attention they receive and are not judgemental (Katcher 2000). A randomized controlled study by Berget et al. (2008) showed that working with farm animals improved coping ability, self-efficacy, symptomatology and quality of life for participants diagnosed with schizophrenia, anxiety, mood and personality disorders. ‘Green exercise is activity in the presence of nature’ (Barton and Pretty 2010, p. 3947) and derives its efficacy from the synergistic benefits of physical activity and exposure to nature (Pretty et al. 2006). Walking, cycling, gardening and conservation are widely facilitated to address specific therapeutic goals. A meta-analysis of 10 UK green exercise studies showed that green exercise improved mood and self-esteem, with individuals with mental health problems showing one of the greatest changes for self-esteem (Barton and Pretty 2010). In the UK, MIND (2007) have argued that GP referral for facilitated green exercise sessions could be as effective as prescribing antidepressants for people with mild to moderate depression. Wilderness (or nature therapy, or adventure therapy) uses outdoor activities – such as rock-climbing or canoeing – in their natural settings to distance people from customary stressors and to create challenging situations with controlled risk for participants, whose experiential learning and self-reflection forms the basis of positive change (Hine et al. 2009). Wilderness therapy can help individuals (often adolescents) with anxiety and depression and/or behavioural problems and can also improve trust and communication within families and groups. It can adopt a specifically psychotherapeutic approach based on the premise that wild nature evokes positive coping behaviours (rather than defensive ones) because of the risk involved, the immediacy of the consequences of one’s actions, and through cooperation within one’s peer group (Berman and Davis-Berman 1995; Itin 1995; both cited in Haubenhofer et al. 2010). In addition to the five green care intervention-types described above, a brief overview of ecotherapy is provided. Ecotherapy is not, strictly speaking, a green care intervention-type but it is often discussed within a green care context. Ecotherapy sees personal health and healing as being directly related to the health of the natural ecosystem of which humans are a part (Davis and Atkins 2009). Ecotherapy integrates health-promotion activities that serve individual, community and global goals (Burls 2007), highlighting that the natural world is an inextricable element of our community and social system, and that ‘the mind-body-world web contains its own freely available healing potentials’ (Buzzell and Chalquist 2009, p. 20). In this sense, ecotherapy is not so much an intervention-type, as an approach to any or all green care interventions (Sempik and Bragg 2013). For example, Chalquist (2009) notes that, in addition to benefitting individuals, horticulture: ‘helps the community too, particularly when it involves growing fruit and vegetables locally, thus decreasing dependency on chemically treated food products seized from exhausted, nitrate-singed soils and trucked or flown in from thousands of miles away.’ (p. 68) This macro-level perspective on human occupation and environmental degradation identifies ecotherapy as an ecological issue, overlapping with green politics and the sustainability agenda. These diverse interventions are all underpinned by the natural green environment. What follows is an overview of how the human relationship with this environment has been conceptualized, and how these theories can inform occupational therapy. The key constructs and theories associated with green care can be understood as conceptual psycho-evolutionary perspectives or a more empirical exploration of the human relationship with the natural world. The biophilia hypothesis suggests that people have an innate desire to connect with nature and that this is strongly determined by survival instincts established early on in our species’ evolution (Wilson 1984; Kellert and Wilson 1993). It sees this affinity as being integral to people’s physical, psychological and social development. In short, it proposes that an attachment to the natural world is hard-wired into humans and is adaptive. Particular aspects of personal development are associated with certain values that nature is seen to possess, such as: 2. A dominionistic value – whereby mastery of nature and/or adversity builds self-esteem 3. A humanistic value – whereby a shared emotional attachment promotes trust, cooperation and sociability 4. A moral value – whereby an appreciation of the wholeness and integrity of the natural world generates feelings of harmony and belonging 5. A naturalistic value – whereby immersion in natural rhythms promotes mental acuity and physical fitness 6. A negativistic (or resisting, questioning) value – whereby a healthy respect, for the power of nature and the sense of wonder it fosters, promotes positive attitudes to fear, risk-taking and self-management 7. A symbolic value – whereby the figurative and metaphorical significance of natural objects, processes and rhythms encourages greater understanding of one’s own life 8. A utilitarian value – whereby one’s dependence on nature’s finite material resources is appreciated, as food, for example. (Kellert and Derr 1998; cited in Burls 2007). The utilitarian value underpins the human ethic of nature conservation and care for biodiversity and is at the core of an ecological perspective of life, as Shoemaker (1994) notes: The green plant is fundamental to all other life. Humankind could perish from this planet and plants of all kinds would continue to grow and thrive. In contrast, the disappearance of plants would be accompanied by the disappearance of all animal life, including humankind. (p. 3) The biophilia hypothesis also theorizes that humans attune to the condition of nearby animals and plants because it is a way of deriving information about their shared environment. An animal at rest signals wellbeing and safety, and this impression is then transmitted to the person. Similarly, healthy plants and flowers convey a relaxed feeling of being in a bountiful natural setting, beneficial for humans (Melson 2000; cited in Sempik et al. 2010). It is estimated that in industrialized nations, people spend between 1% and 5% of their time outdoors; the lowest amount of time at any point in human history (Chalquist 2009). The health implications of this are wide-ranging. Wilcock (2006) suggested that cultural values and norms are disconnecting people from the natural world that shaped our evolutionary path, so that modern life is less orientated to the older biopsychosocial capacities necessary for maintaining health. This offers fewer opportunities to recover from mental stress (Pretty et al. 2005). Modern living can subject people to a bombardment of sensory overstimulation that may lead to damaging levels of psychological and physiological arousal, whereas natural green environments that include plants contain patterns that reduce stress levels (Ulrich et al. 1991). This makes accessing the natural outdoors environment a potentially important issue for mental health service users, whose contact with nature may be limited by hospital admissions, urban living and/or low income. The most widely quoted theory in the context of green care (particularly in relation to horticultural interventions) is Attention Restoration Theory (Kaplan and Kaplan 1989; Kaplan 1995). It posits that natural environments offer respite from the mental fatigue that results from having to constantly inhibit competing influences when trying to direct one’s attention towards a specific task. It argues that the presence of nature is inherently interesting or stimulating and requires no effort in order to engage with it, and describes this phenomenon as fascination. Fascination has a positive impact on individuals’ cognitive ability and restores the ability to focus attention. It is an essential feature of a restorative environment, which is said to comprise the following: ■ Being away – the subjective sense of having escaped, or feeling removed (physically or conceptually) from situations that would normally be stressful, or place a burden on directed attention ■ Extent – a sense that the environment is ‘rich enough and coherent enough so that it constitutes a whole other world’ (Kaplan 1995, p.173) which the individual can become immersed in ■ Compatibility – the individual’s inclinations to become active are matched by the opportunities for action which the environment affords. In other words, an individual may feel inclined to weed a patch of earth, or pick a ripe apple – which has obvious implications for their motivation. Kaplan and Kaplan (2011) note how easily people are impaired by becoming overloaded with information. They use the term reasonableness to describe the kind of wellbeing derived from enhanced information-processing (including better concentration, greater capacity for reflection, and enhanced planning and problem-solving). They contrast this with the irritability, impulsiveness, impatience, distractibility and error-prone performance associated with attentional fatigue. Occupational forms associated with green care (such as gardening, conservation work or bushcraft), which simultaneously foster fascination and offer a range of compatible activities, can promote instinctive engagement and enhance motivation. Studies consistently show people prefer environments where they anticipate they will be able to function effectively (Kaplan and Kaplan 2011). They respond unconsciously to cues for such environments, preferring those that have coherence (that is, they can be made sense of, have some degree of predictability, and are knowable) but which also have complexity (that is, they are alluring and offer the possibility that there is more to be learned). This is typified by the human attraction to ‘the bend in the path’ (Kaplan and Kaplan 2011, p. 312). This is explored more fully later as an occupational science phenomenon. This section focuses on phenomena and constructs with an empirical basis, in that they are all drawn from close observation and inquiry into people’s experiences, as they engage with the natural world. Such experiences may be considered as ‘here and now’ manifestations of the evolutionary viewpoints presented earlier. Maller et al.’s (2002) systematic review of anecdotal, theoretical and empirical evidence showed that simple human contact with nature fostered recovery from mental fatigue, restored concentration, was recuperative, increased capacity to cope with stress, improved productivity and enhanced people’s life satisfaction and general outlook on life. Chalquist’s (2009) overview of the research-based evidence for nature-based interventions underlines that reconnection with the natural world can impact on and alleviate anxiety, frustration, and depression – and bring a greater capacity for health, self-esteem, self-relatedness, social connectedness and joy. What follows is an overview of some of the processes through which this kind of impact is seen to occur. The aim is to encourage thinking about how green care occupations can be translated into occupational therapy. Sensory processing refers to the way messages from the senses are processed by the nervous system, so they can inform motor and behavioural responses (Dunn 2009). Individual differences will influence a person’s sensory diet, the combination of preferred sensorimotor experiences that optimize individuals’ functioning in a given environment. Green care settings offer a potentially rich, nourishing and varied sensory diet. Plants and flowers may be cultivated specifically for their shape, colour, scent and texture, for example in sensory gardens. Green care settings also encompass the visual appeal of landscape and light, outdoor smells and sensations (such as hearing birdsong) and a wide range of sensory experiences related to changing seasons and the weather. There are other sensations too, such as the feeling of excitement and exhilaration associated with a sense of adventure on taking positive risks and having fun. Sensory-based approaches are particularly relevant in mental health practice. People living with schizophrenia may have sensory processing difficulties in processing motion, decoding facial information, and recognizing and conveying emotion in the voice, for example, which are likely to have a significant impact on social and vocational participation (Champagne and Frederick 2011). Similar sensory problems may arise for people living with dementia, or with a learning disability (see Ch. 26). Information can be extracted quickly from natural green environments, enabling individuals to function effectively. Therefore, green care settings may be conducive to achieving a balance of sensory stimulation to promote optimal cognitive functioning (Dunn 2009; Kaplan and Kaplan 2011). An essential therapeutic advantage of green care is that the physical act of doing – such as digging, sowing, weeding or watering – amplifies the existing cognitive benefits of simply being in a natural green environment through its sensory integrative function. The fact that rich sensory experiences are abundant, uncontrived and naturally integrated through occupation is crucial to green care outcomes. Green care activities heighten people’s awareness of time in terms of seasonal change or daily rhythms (such as a regular time for milking the cows). Clark (1997) has called this temporality, suggesting that the pace of life not only bombards the senses but can dislocate the temporality of occupations, resulting in ‘doing without being’ (Clark 1997, p. 86), or a disconnection from self. Simo (2011) offers this perspective: Gardening enables human beings to reconnect with nature and emerge from their immersion in a cyber-world dominated by the instrumental reasoning which orders people to fit the rational economy of its design and the consequent ethics of the machine society. (p. 358)

Green Care and Occupational Therapy

INTRODUCTION

Green Care and Occupational Therapy

Chapter Aims and Structure

GREEN CARE INTERVENTIONS

Horticulture-Based Approaches

Care Farming

Animal-Assisted Interventions

Facilitated Green Exercise

Wilderness Therapy

Ecotherapy

GREEN CARE CONSTRUCTS AND THEORIES

Psycho-Evolutionary Perspectives

The Biophilia Hypothesis

An Overload and Arousal Perspective

Attention Restoration Theory

The Human Relationship With the Natural World

Sensory Processing

Temporality

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree