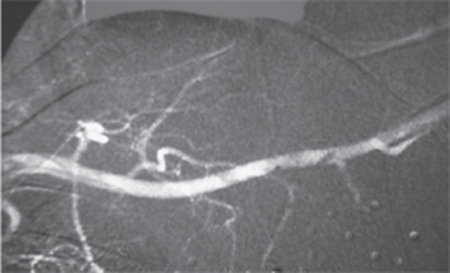

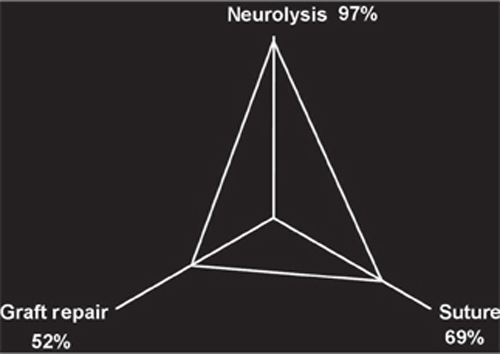

4 Gunshot Wounds to the Brachial Plexus A 35-year-old man received a single shotgun blast at close proximity to his left upper chest 3 months earlier. The wadding was lost, but the entry site disclosed a very tight pellet pattern. The patient sustained a pneumothorax that required a chest tube. Chest film showed dispersion of the pellets across the chest wall. An arteriogram was done acutely that night, which showed no evidence of vessel occlusion (Fig. 4–1). He presented with increasingly painful paresthesias radiating from the left axilla distally down the medial arm to the ulnar two fingertips. The pain was not controlled adequately pharmacologically. Physical examination revealed mild weakness (4+/5) in the lumbricales to the ring and little digits, and in the biceps. Otherwise complete muscle testing was normal. Sensation to light touch and pin was subjectively diminished (S4) in the distributions of the medial antebrachial cutaneous and medial brachial cutaneous nerves but was otherwise normal. Range of motion in the shoulder was extremely limited due to pain. Electrodiagnostic studies demonstrated absent left medial antebrachial cutaneous and ulnar sensory potentials. Mild denervation was found in the latissimus dorsi and the deltoid. Repeat angiography did not reveal any evidence of a pseudoaneurysm. Surgical neurolysis was undertaken in an attempt to improve the neuropathic pain. An infraclavicular approach was utilized. The neural elements were identified and neurolysed. Dense scar was encountered under the pectoralis major insertion and involved the median, ulnar, and medial antebrachial cutaneous nerves. Nerve action potentials (NAPs) were recorded in all nerves. Numerous pellets were removed. Intraoperative radiographs were taken in two positions: one with the nerves in their anatomical position and the second with the nerves retracted superiorly. This verified that none of the remaining pellets was located intraneurally. Immediately postoperatively, his pain was improved and he had significantly improved range of motion in his arm. At 1-year follow-up, he was off pain medication and had 5/5 motor function in all muscle groups and normal sensation. Gunshot (shotgun) injury to the brachial plexus Figure 4–1 Arteriogram showing a patent axillary artery. Note the pellets in proximity to the vessel. Patients with gunshot wounds to the brachial plexus should receive thorough evaluation acutely by a trauma service. Associated injuries are very common and may include serious vascular injury (e.g., occlusion, expanding hematoma, pseudoaneurysm, fistula), lung injuries (e.g., pneumo- or hemothorax, contusions), and orthopedic complications (e.g., clavicle, rib, scapular, and humeral fractures). Neurological function in the affected limb should be carefully documented. Initial treatment should include wound debridement, antibiotic therapy, and tetanus toxoid. Angiography should be considered in those patients thought to have underlying vascular injury. In general, patients with neurological injuries should be managed expectantly. They should be followed for 3 to 6 months with serial clinical and electrical examinations and receive physical therapy to increase mobility during this observational phase. Those who do not improve may benefit from surgical exploration with intraoperative NAPs. In one large series of gunshot wound injuries to the brachial plexus, the largest category represents those patients with incomplete loss involving multiple elements that improve spontaneously in the early months following the injury. Occasionally patients with complete neurological loss in one or more elements show early recovery as well. Patients with isolated injury to C8 and T1 spinal nerves, lower trunk, and medial cord, and those referred late (usually after 1 year) do not fare well from standard methods of peripheral nerve surgery and typically should not undergo this form of reconstruction. All patients should undergo physical therapy during periods of observation. The most common indication for nerve surgery is patients with complete injury to one or more elements that is typically helped by surgery (i.e., C5, 6, and 7 spinal nerves, upper trunk, middle trunk, lateral cord, posterior cord, and their outflows) that has not improved spontaneously. Other indications for surgery include patients with incomplete lesions associated with neuropathic pain refractory to medication, as in our patient. Patients with sympathetically mediated pain who do not respond to appropriate medical management and do not receive lasting relief from sympathetic block may be candidates for cervical sympathectomy; neurolysis in these patients does not do well. In addition, many patients deemed poor candidates for standard peripheral nerve surgery (such as those with nerve injury to C8, T1, lower trunk, or medial cord or patients presenting in a delayed manner) might still benefit from other modes of reconstruction (such as tendon transfers or joint fusions); referral to a hand surgeon should be considered. Finally, spinal cord stimulation or dorsal root entry zone (DREZ) lesioning procedures should be considered in cases of intractable pain. In general, the timing of surgery following gunshot wounds is similar to that for stretch injuries, namely, 3 to 6 months after injury, if there has not been any clinical or electrical improvement. This is due to the fact that many patients show spontaneous recovery. The vast majority of these injuries result from contusion or blast effect and are lesions in continuity rather than transections. Early surgery is indicated when vascular complications necessitate earlier intervention, such as for hematoma, fistula, or pseudoaneurysm. In the acute phase, the zone of injury to the neural elements is difficult to establish at operation. In addition, NAPs are best performed after 2 months. Transected elements should be tagged and maintained at length for secondary surgery 2 to 3 months later as a contusive element was present as well. In our experience, nerve repairs performed acutely typically do not yield good results. We have reoperated several patients in whom the emergent vascular repairs incorporated neural elements; in some cases, these involved the posterior cord (which may not have been identified at the primary surgery). Prior to any surgery, patients should be reassessed to ensure that there is no evidence of a pseudoaneurysm. If a mass lesion, bruit, or thrill is present, angiography should be performed. In general, a wide exposure of the brachial plexus is necessary in patients after gunshot wounds. The dissection is often quite difficult and tedious due to the diffuse scarring. This is more difficult in the infraclavicular region where the axillary vessels need to be mobilized more than the subclavian vessels in the supraclavicular region. The axillary vessels have often been injured or previously repaired. Neural elements are typically quite adherent to them, and circumferential control of the vessels is necessary to perform the dissection of all of the neural elements, especially the posterior cord and its branches. If regenerative NAPs are obtained in patients, then neurolysis of the elements is performed. Approximately half of the elements have preserved NAPs. Regenerative NAPs across a lesion predate recovery seen when recording to muscle or assessing muscle contraction. If NAPs are not obtained, then resection and grafting are usually employed because end to end nerve reapproximation is rarely possible. In select cases, distal nerve transfers (such as an ulnar or median fascicular transfer to the biceps and/or brachialis muscles, or a triceps branch to the axillary nerve) might also be considered. The best clinical results are obtained for incomplete injuries and complete injuries that show early spontaneous recovery. Elements that have a regenerative NAP have the best outcome in the surgical group. Of these, 90% obtain good or excellent results. Those patients who required suturing or grafting based on an absent NAP do not fare as well as patients who had neurolysis alone when a NAP was obtained (Fig. 4–2). Good or better results may be obtained in ˜60% of patients with repairs involving C5, C6, and C7 spinal nerves, upper and middle trunks, or lateral and posterior cords. Recovery of function after repair of C8 and T1 spinal nerves, lower trunk, and medial cord rarely if ever occurred in adults but can be accomplished with other methods of soft tissue or bony reconstruction. Neuropathic pain may be improved in ˜50% of those patients treated surgically.

Case Presentation

Case Presentation

Diagnosis

Diagnosis

Management Options

Management Options

Surgical Treatment

Surgical Treatment

Outcome and Prognosis

Outcome and Prognosis

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree