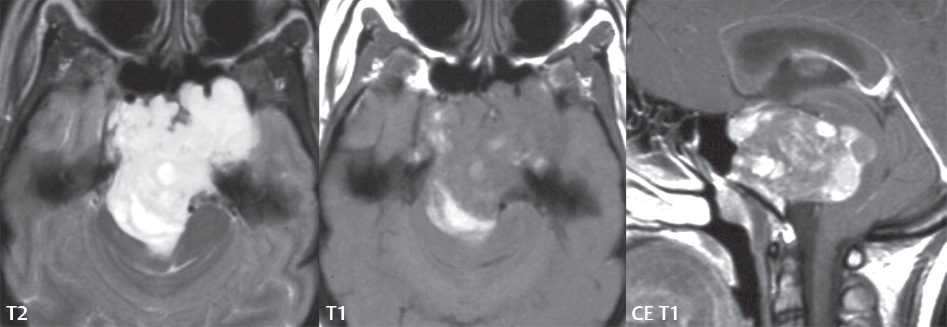

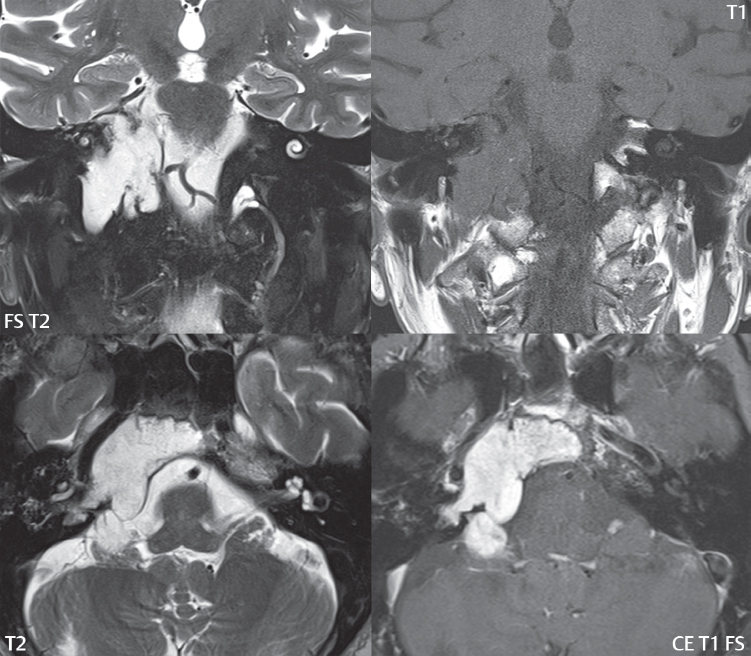

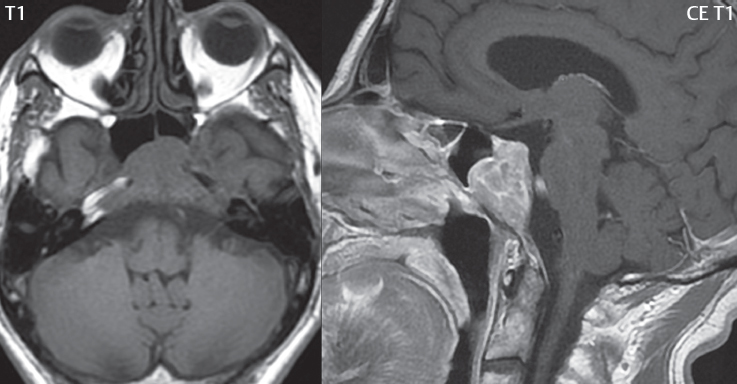

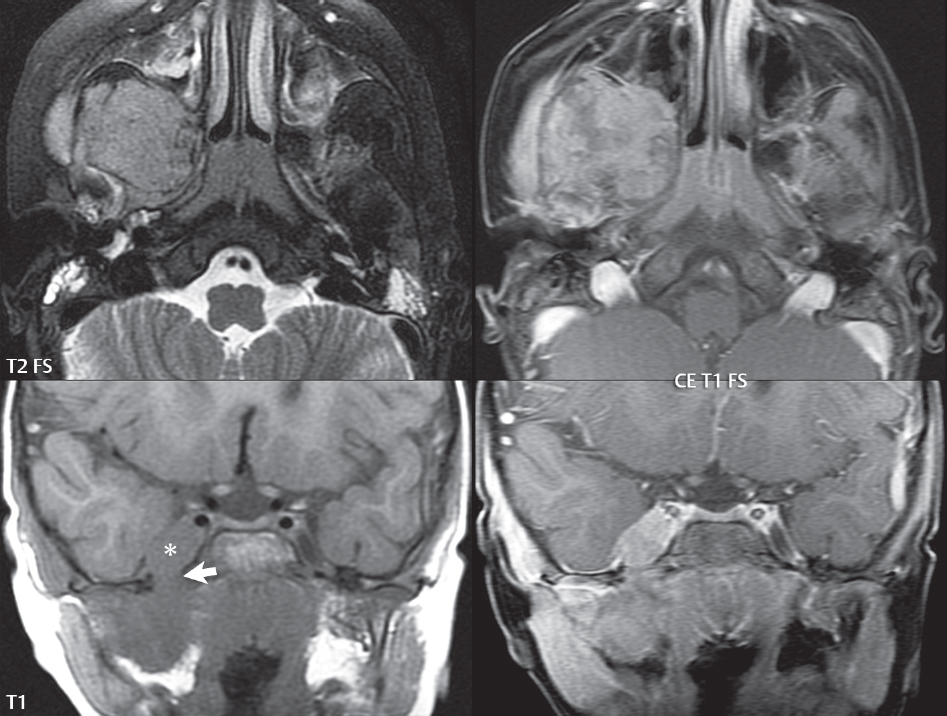

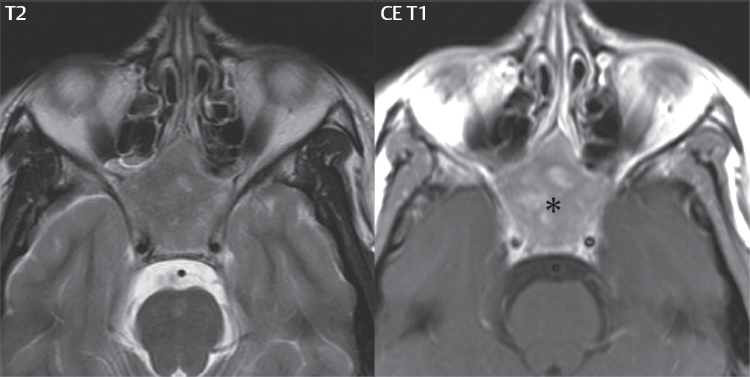

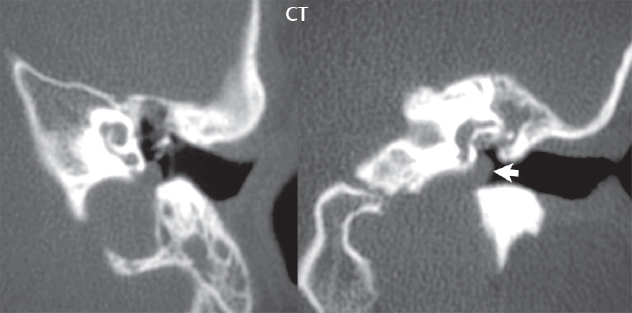

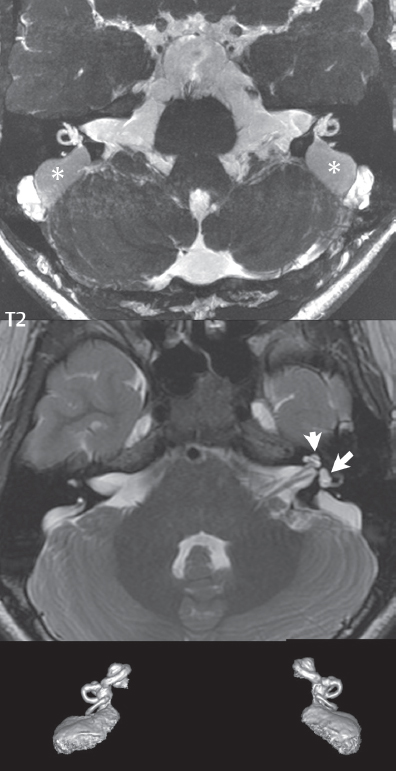

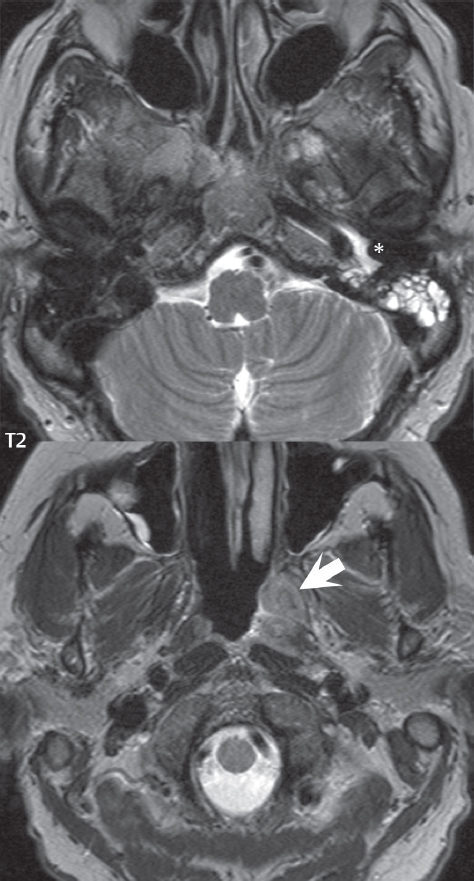

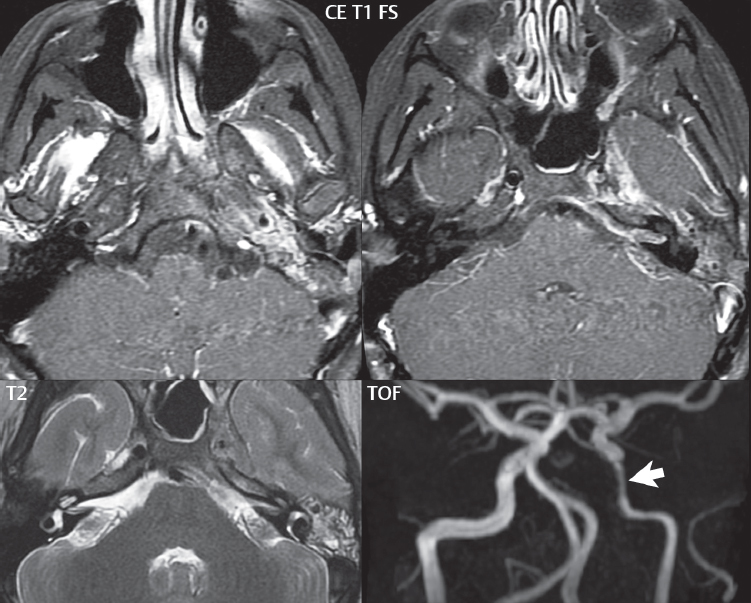

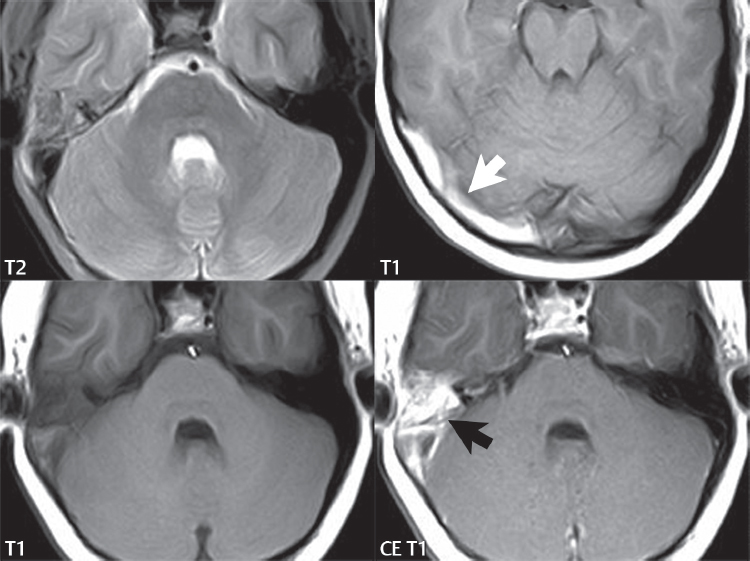

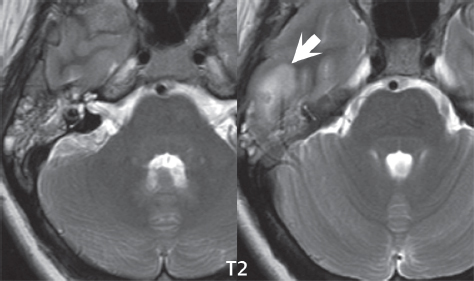

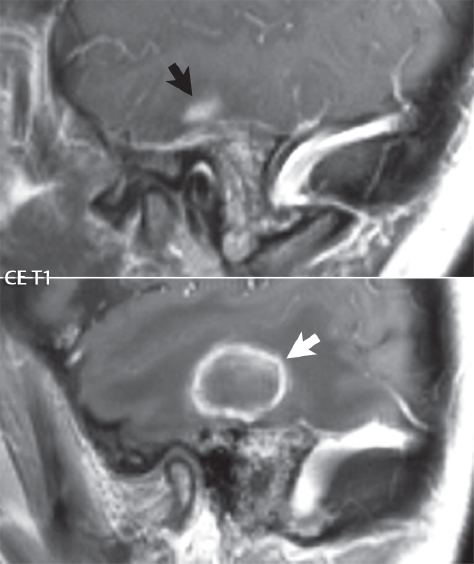

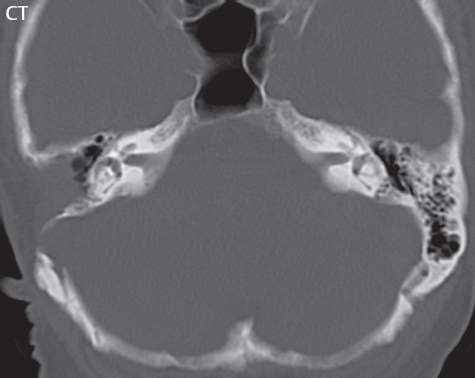

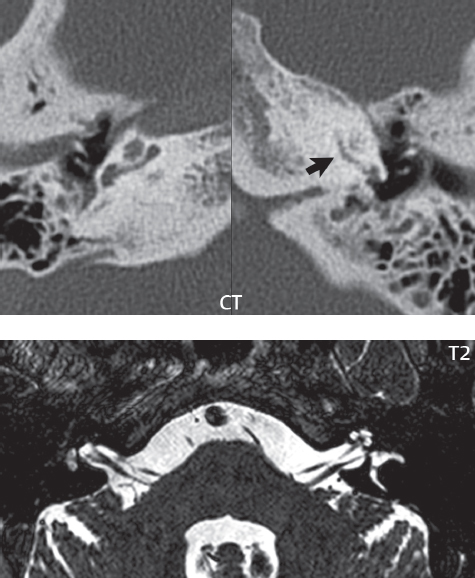

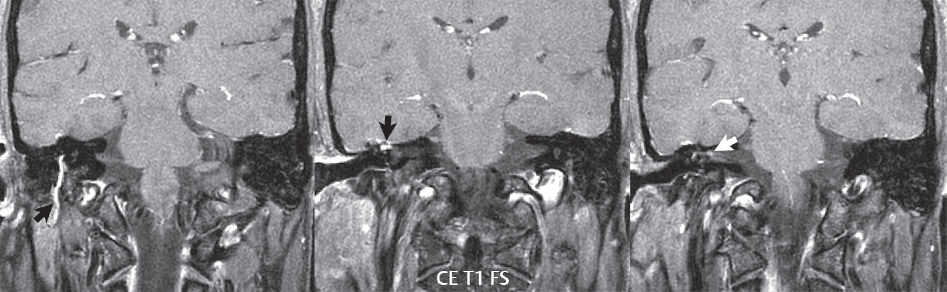

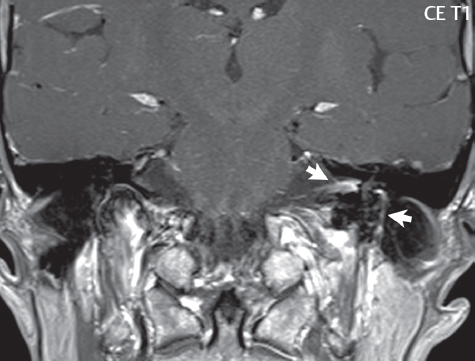

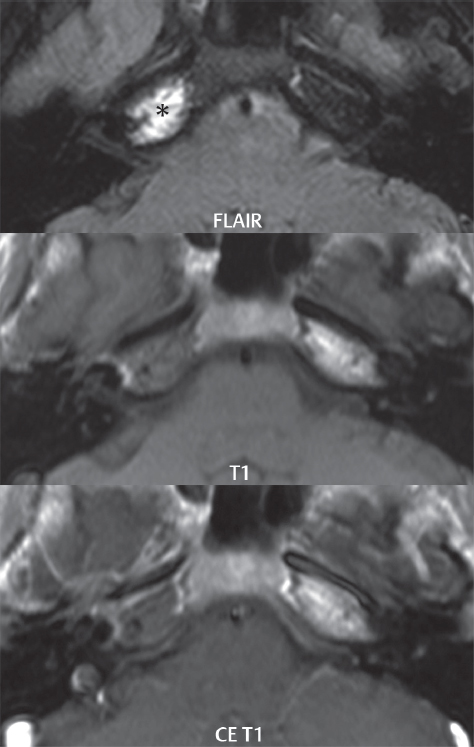

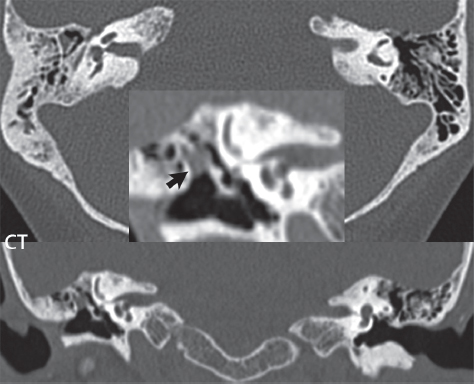

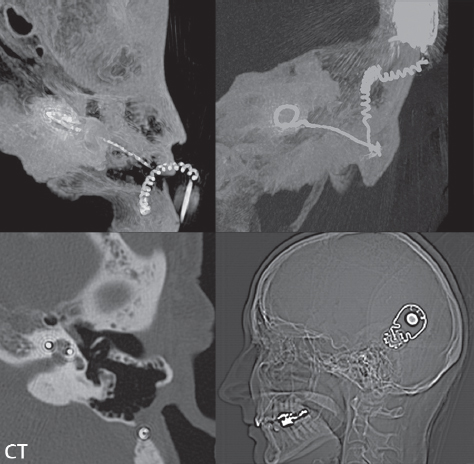

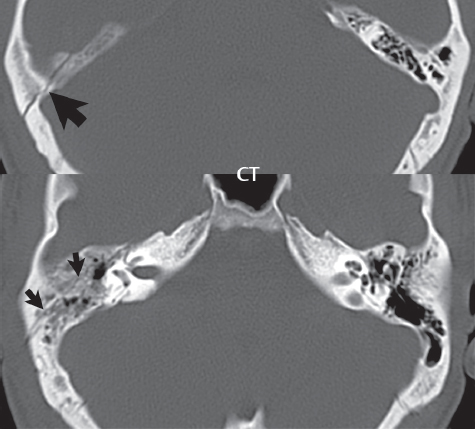

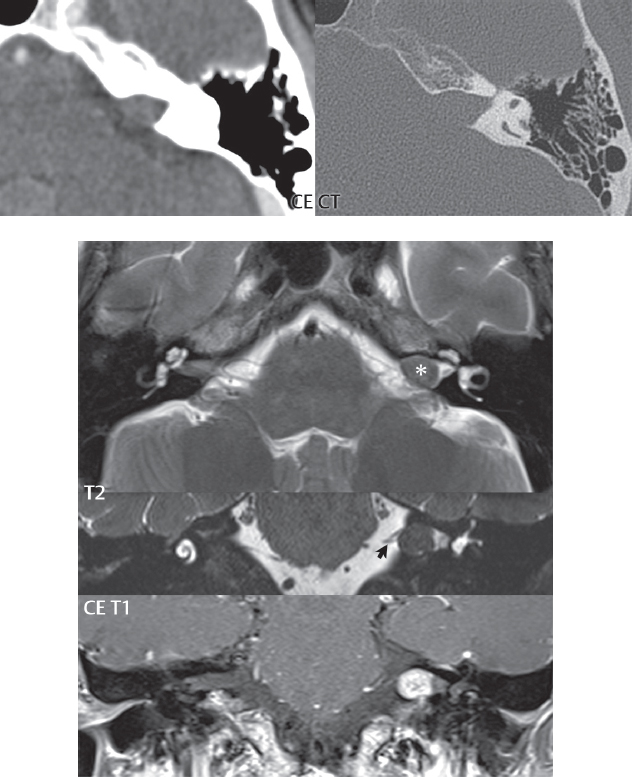

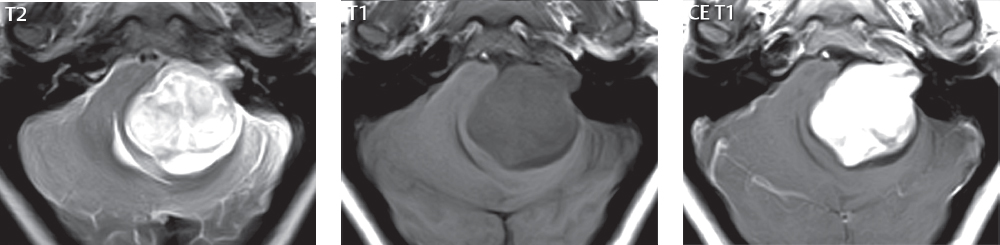

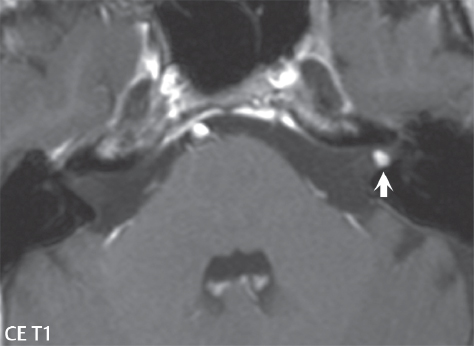

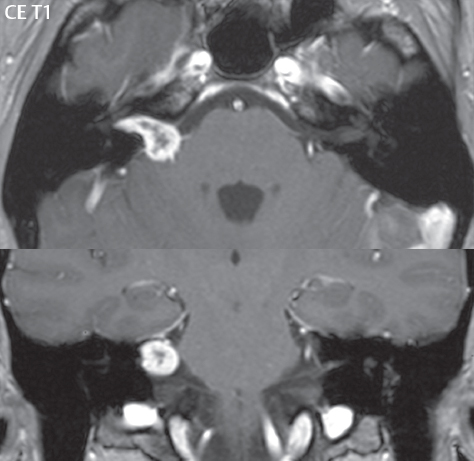

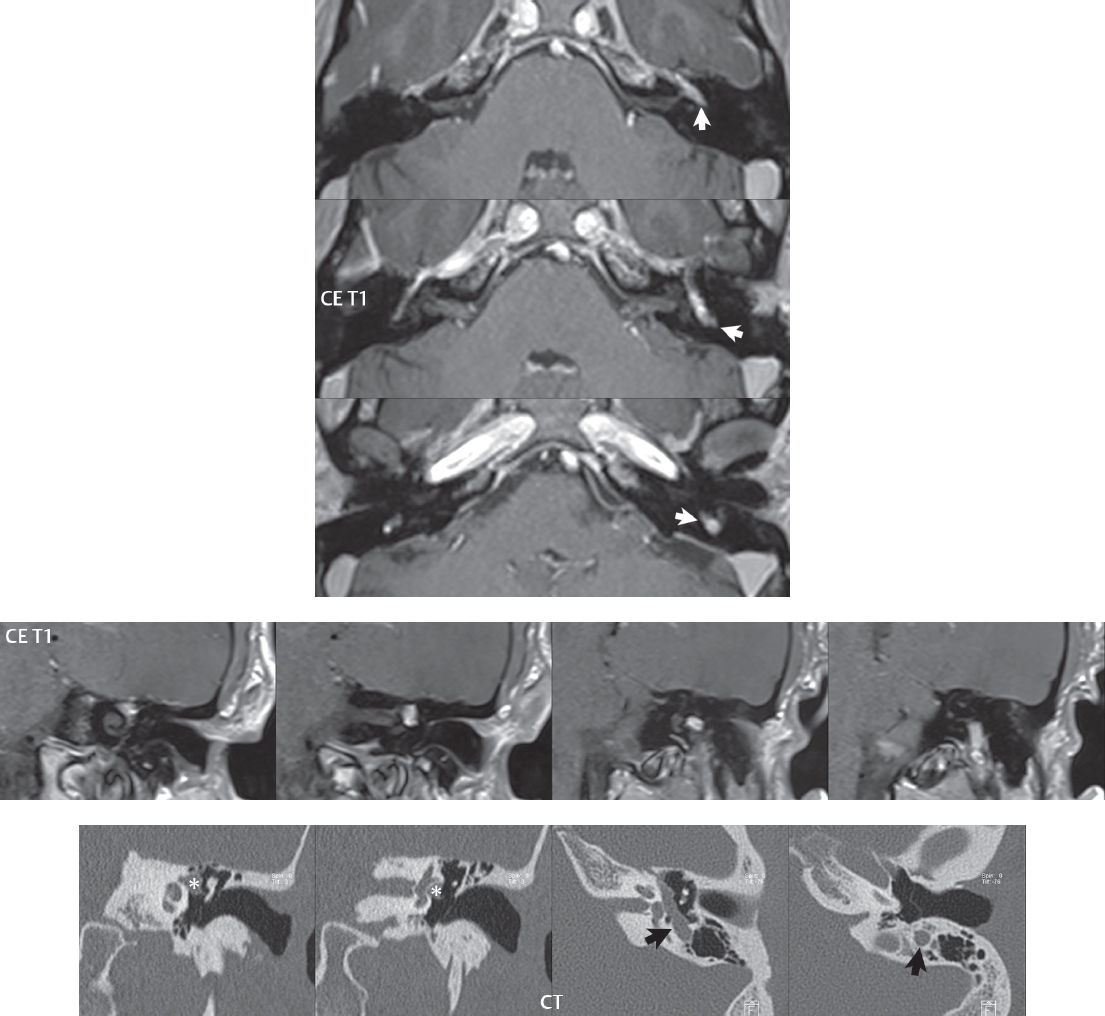

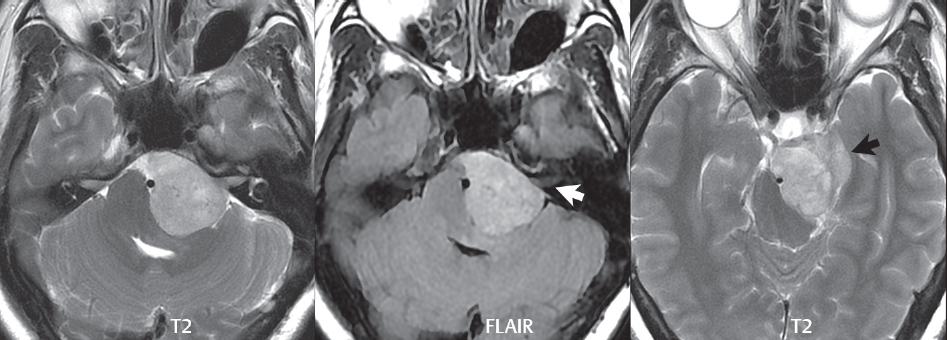

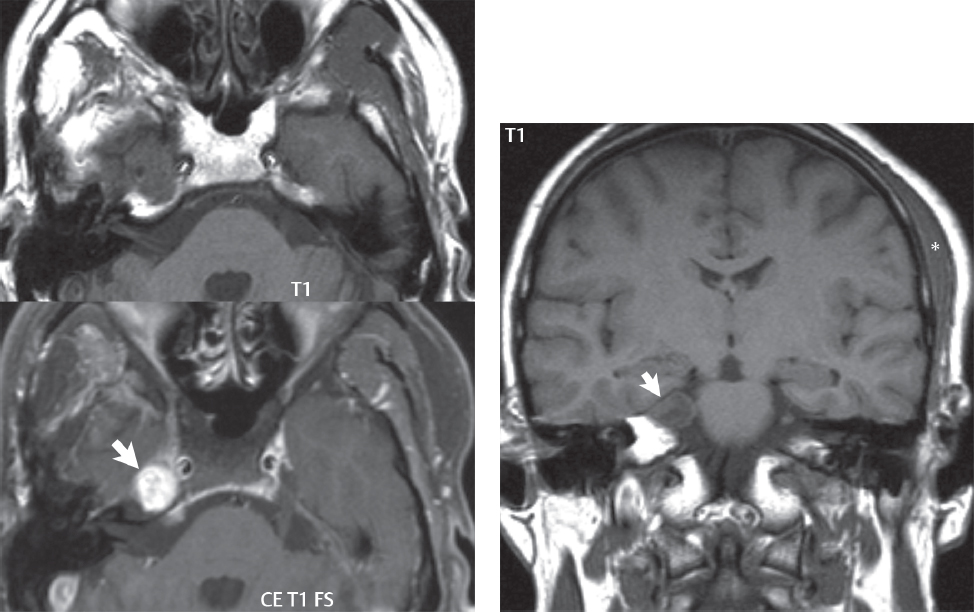

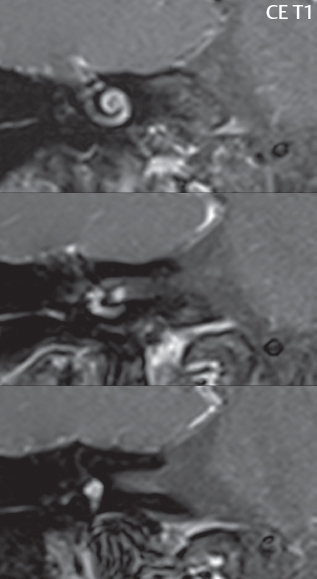

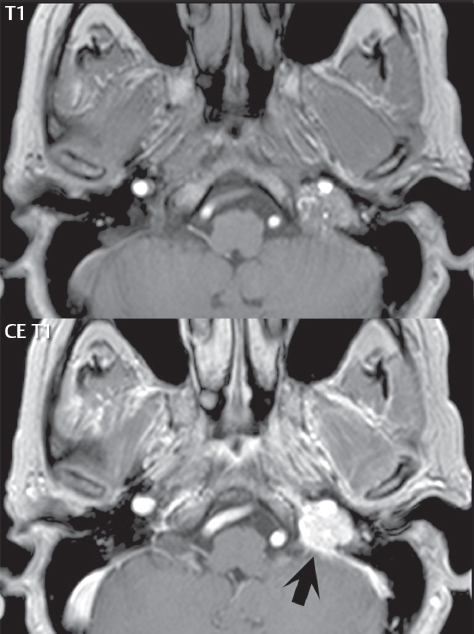

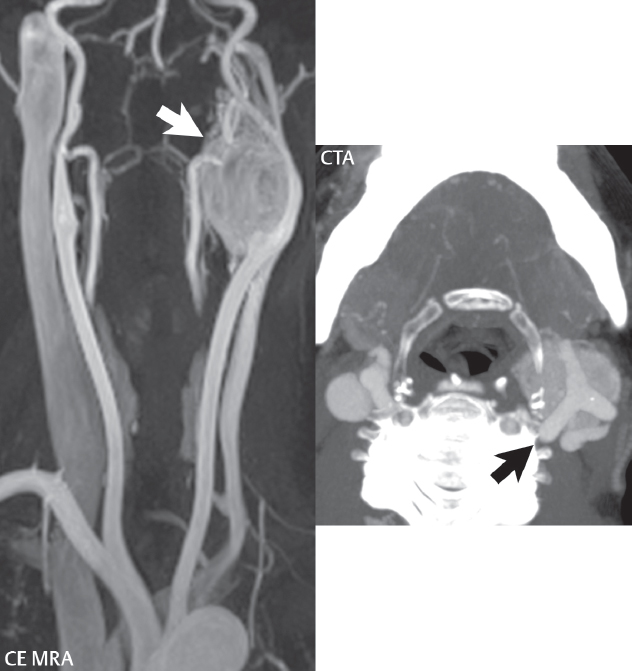

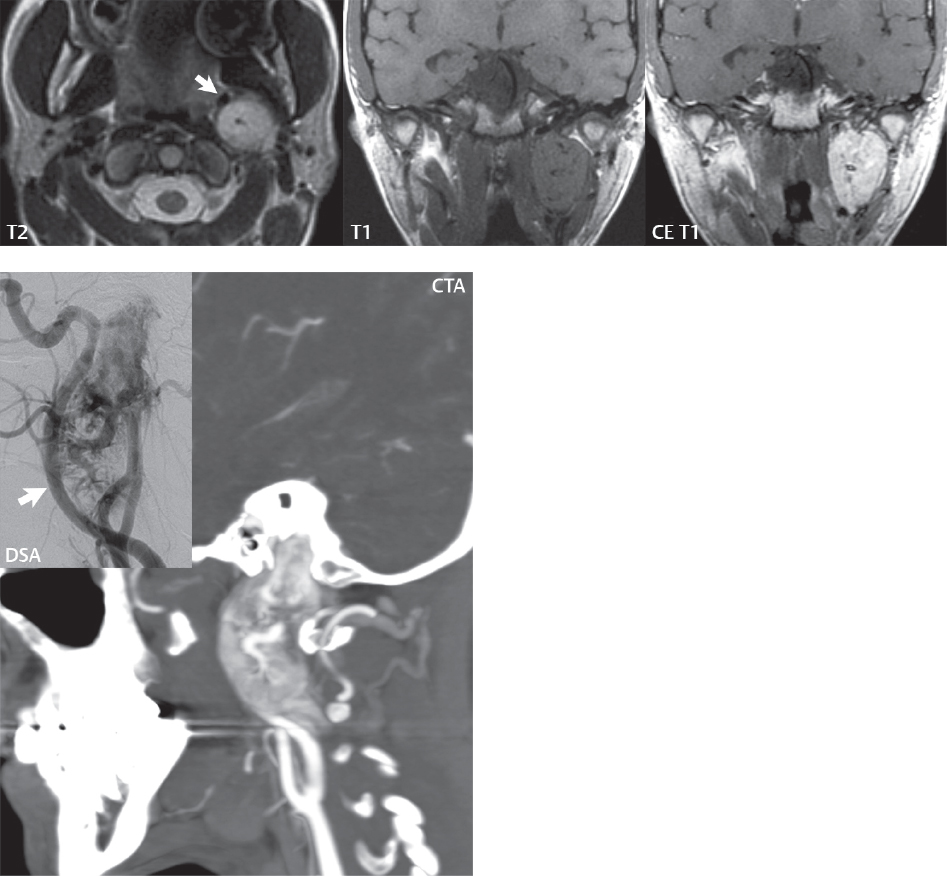

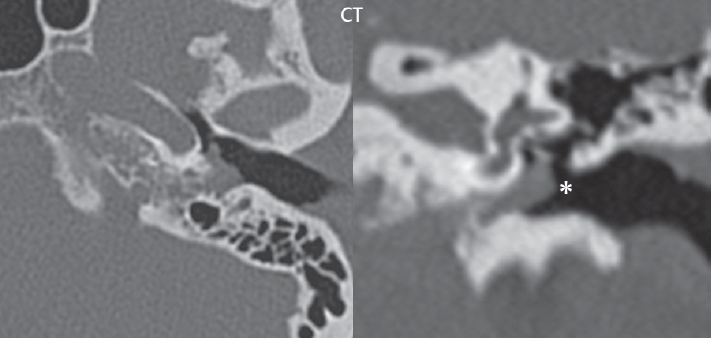

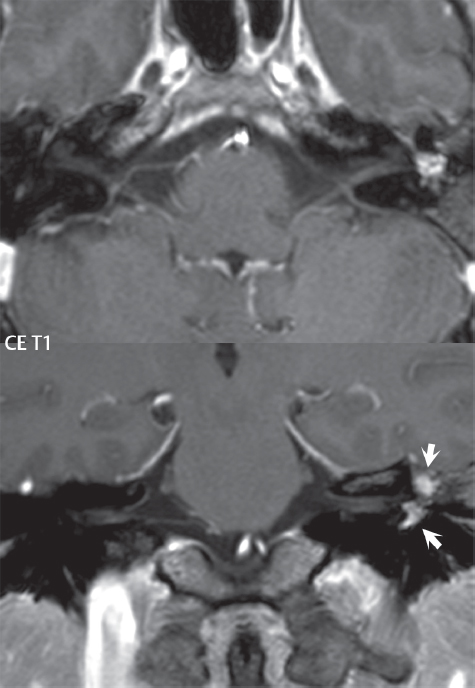

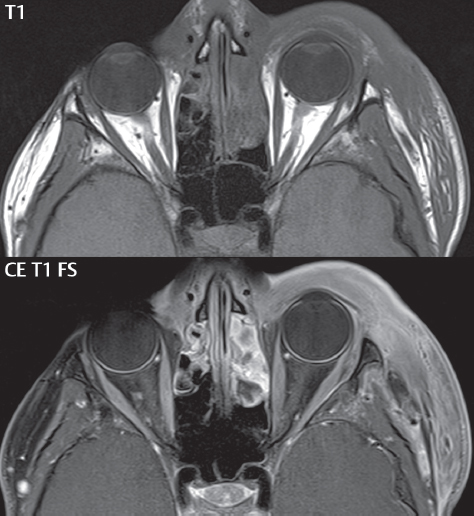

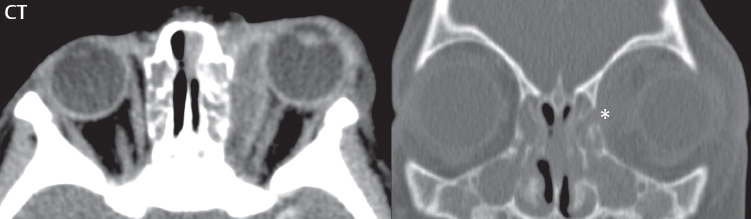

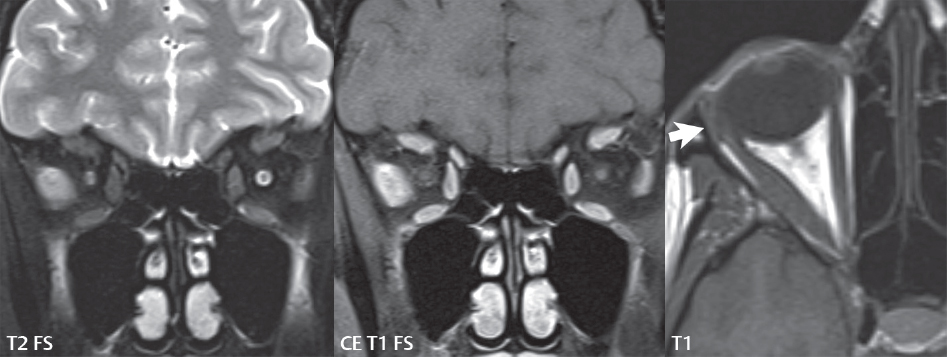

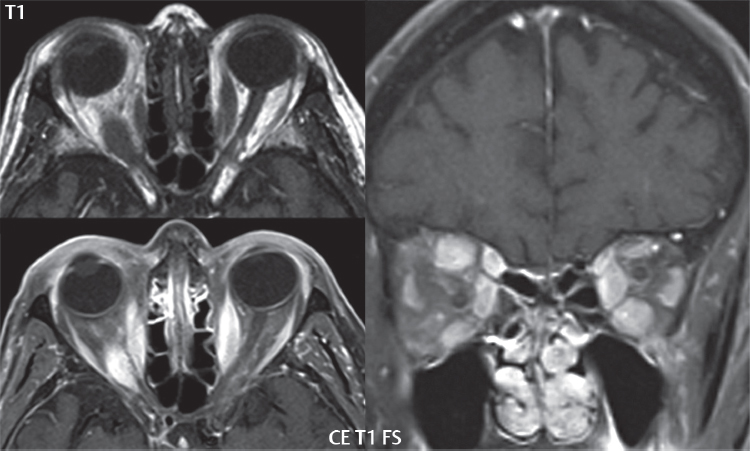

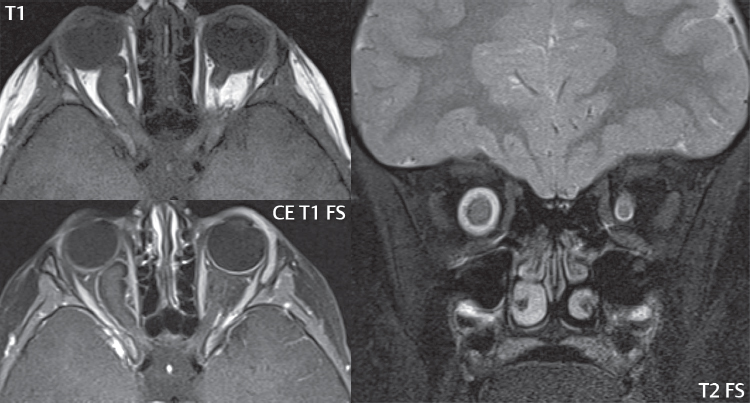

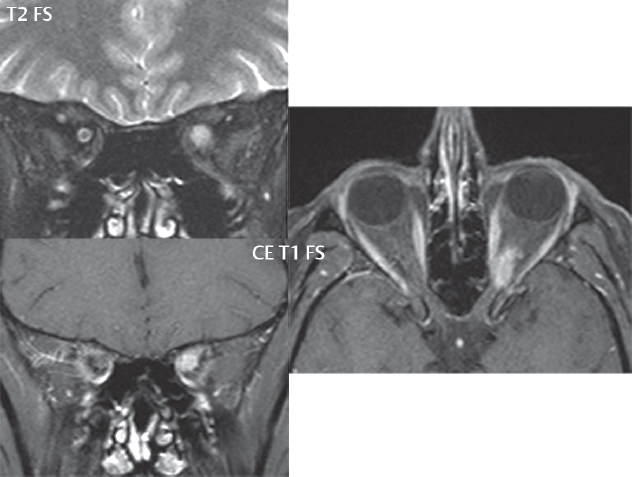

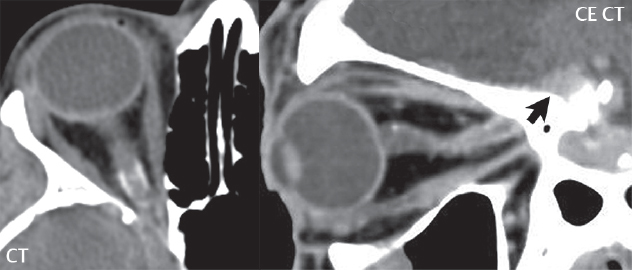

2 Head and Neck Addressing normal anatomy, the sphenoid bone forms the foundation of the central skull base. It forms the floor of the middle cranial fossa, provides structure for the cavernous sinus and a base for the pituitary gland. The shape of the sphenoid bone is bird-like with outstretched wings, being composed of the central body, two sets of wings (greater, lesser), and the medial and lateral pterygoid plates (inferiorly). Important foramina include the foramen rotundum, located medially in the anterior greater wing and containing the maxillary nerve (cranial nerve [CN] V2); the foramen ovale, located in the floor of the middle cranial fossa and containing the mandibular nerve (CN V3); and the foramen spinosum, located posterolateral to the foramen ovale and containing the middle meningeal artery and the meningeal branch of the mandibular nerve. The cavernous sinus borders the pituitary gland on each side, and contains medially the internal carotid artery (ICA), with the abducens nerve (CN VI) just inferior and lateral to the ICA. Laterally, the cavernous sinus contains (from superior to inferior) the oculomotor nerve (CN III), the trochlear nerve (CN IV), and the ophthalmic (CN V1) and maxillary (CN V2) divisions of the trigeminal nerve. Blood flows into the cavernous sinus from the superior and inferior ophthalmic veins, superficial cortical veins, and the sphenoparietal sinus. The drainage of the cavernous sinus is via the superior and inferior petrosal sinuses. The clivus is not properly a separate bone, but rather the gradual sloping bony process that extends from the dorsum sellae to the foramen magnum. The clivus thus includes a portion of the body of the sphenoid bone (basisphenoid) and the basilar (anterior) portion of the occipital bone (basiocciput). The most important (common) developmental abnormality affecting the middle cranial fossa (and thus by proximity the skull base) is an arachnoid cyst, a lesion that can also be traumatic in origin. By definition, an arachnoid cyst contains cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). It can expand with time. Of all locations, for this entity, the middle cranial fossa is the most common. Bony changes may be present, including thinning and remodeling of the adjacent sphenoid wings. Meningiomas are the most common benign skull base tumor. One-third of all meningiomas involve the skull base, with most of those involving the sphenoid wing. Bony hyperostosis is not uncommon. For lesions adjacent to the cavernous sinus, it should be kept in mind that sinus invasion is common. Other common locations for a meningioma include the olfactory groove and planum sphenoidale. Pituitary macroadenomas are discussed in depth in Chapter 1, but are relevant to the skull base and surrounding structures due to their propensity for cavernous sinus invasion and optic chiasm compression. Chordomas and chondrosarcomas are the two malignant tumors of the skull base of note. Chordomas arise from remnants of embryonic notochord, with the second most common location being the clivus (after the sacrum). These are usually midline, destructive, infiltrative, slow-growing tumors and are often large on presentation with a poor prognosis. Areas of dystrophic calcification are common on computed tomography (CT). On magnetic resonance (MR), chordomas appear relatively well-defined and enhance postcontrast (Fig. 2.1). A characteristic feature of this tumor is “thumb-printing” on the anterior brainstem, typically the pons. Chondrosarcomas are found along synchondroses, with a propensity to occur in the skull base at the petrooccipital synchondrosis (Fig. 2.2). Thus, these tumors are usually off midline (as opposed to chordomas). Tumor spread is usually by local invasion with destruction of adjacent bone. Calcification is characteristic, but the degree of calcification is widely variable. Resection is often incomplete, and recurrence is common. Increasingly, atypical presentations for lymphoma have been reported, and lymphoma needs to be included in the differential diagnosis of clivus lesions (Fig. 2.3). Metastases to the skull base are more common than primary bone tumors. Skull base invasion can also occur secondarily with adjacent malignant tumors—for example, nasopharyngeal carcinoma and, in children, rhabdomyosarcoma (Fig. 2.4). Two other entities to keep in mind, due to some propensity for skull base involvement, are Paget disease and fibrous dysplasia (Fig. 2.5). Most fractures that involve the skull base are extensions of cranial vault fractures. Thin section CT with bone algorithm reconstruction is the method of choice for evaluation. Clinical presentations include CSF otorrhea/rhinorrhea, hemotympanum, and cranial nerve deficits. The temporal bone is divided into five parts, which are subsequently described. The squamous portion (1) is anterolateral, forming the upper part of the temporal bone. It is thin and shell-like, and forms the lateral wall of the middle cranial fossa. The temporalis muscle attaches to the squamous portion of the temporal bone. The zygomatic process arises from the lower portion and arches anteriorly, with the masseter muscle originating from its medial surface. The mastoid portion (2) contains the antrum (a large central mastoid air cell) which communicates posteriorly with the smaller mastoid air cells and anteriorly with the epitympanum (attic) via a small canal (the aditus ad antrum). The petrous portion (3) lies at the base of the skull between the sphenoid bone anteriorly and the occipital bone posteriorly. The petrous portion contains the internal auditory canal (IAC), with its opening (the porus acusticus), and the membranous and bony labyrinths of the inner ear. The IAC is divided into upper and lower compartments by a bony crest, the crista falciformis. The upper compartment contains the facial nerve (CN VII) anteriorly and the superior vestibular division of CN VIII posteriorly. The lower compartment contains the cochlear division of CN VIII anteriorly and the inferior vestibular division of CN VIII posteriorly. The jugular foramen is bordered by the petrous temporal bone anteriorly and the occipital bone posteriorly. The jugular foramen has two compartments, the smaller pars nervosa (anteromedial) which contains the inferior petrosal sinus and the glossopharyngeal nerve (CN IX), and the larger pars vascularis (posterolateral) which contains the internal jugular vein, the vagus nerve (CN X), and the spinal accessory nerve (CN XI). The tympanic part of the temporal bone (4) is a small curved plate surrounding the external auditory canal (EAC). The styloid process (5) projects down and anteriorly from the undersurface of the temporal bone, just anterior to the stylomastoid foramen. Fig. 2.1 Chordoma. A large destructive, expansile midline mass is seen, arising from the clivus, with classic T2 hyperintensity. Additional characteristic findings are seen on pre- and postcontrast T1-weighted scans. Foci of hyperintensity are present within the mass on the axial precontrast T1-weighted scan, consistent with hemorrhage and/or mucinous material. The sagittal postcontrast image reveals the thumb-like indentation of the lesion upon the pons, and the honeycomb-like enhancement due to large cystic/necrotic areas. Fig. 2.2 Chondrosarcoma of the skull base. Chondroid tumors are most often located off midline, due to their propensity to occur (when located in the skull base) at the petroclival synchondrosis. High signal intensity on T2-weighted scans is common, as illustrated in this patient. Enhancement is reported to be often mild, in distinction to the case presented (with prominent enhancement). Most chondrosarcomas are well- or moderately differentiated and slow growing, with lobulated margins also characteristic. Fig. 2.4 Rhabdomyosarcoma. Axial images reveal a large, mildly heterogeneous, mass lesion in the right masticator space with local bone destruction and mild diffuse enhancement. The lesion is hyperintense to normal muscle on the T2-weighted scan and enhances postcontrast. Intracranial perineural tumor spread along CN V3 is evident extending through an enlarged foramen ovale (arrow) and into the Meckel cave (*) and cavernous sinus, on coronal images. Clinical presentation is typically in the first two decades of life, with the patient in this instance a 3-year-old child. The middle ear (tympanic cavity) is air-filled (via the eustachian tube from the nasopharynx) and traversed by the auditory ossicles (which connect the lateral and medial walls). The tympanic membrane (TM) separates the tympanic cavity from the EAC. There are three parts: the epitympanum, mesotympanum, and hypotympanum. The superior limit of the epitympanum (attic) is the tegmen tympani (which separates the epitympanum from the middle cranial fossa) and the inferior margin is defined by a plane between the scutum (junction of lateral attic wall and roof of the EAC) and the tympanic segment of CN VII. Thus, it lies above the attachment of the TM. The lateral epitympanic recess, also known as Prussak space, is the classic location of acquired cholesteatomas. The head and body of the malleus and the short process of the incus lie in the epitympanum. The mesotympanum lies below the epitympanum, directly medial to the TM, separated from the hypotympanum below which lies inferior to the TM attachment. The mesotympanum contains the manubrium of the malleus, long process of the incus, the stapes, and the stapedius and tensor tympani muscles. The medial (labyrinthine) wall separates the middle and inner ears, and contains the oval and round windows, lateral semicircular canal, and tympanic segment of CN VII. The small hypotympanum is the inferior part of the tympanic cavity, below the cochlear promontory, and its floor separates the tympanic cavity from the jugular fossa. The facial nerve (CN VII) enters the temporal bone via the porus acusticus/IAC. The labyrinthine segment extends from the fundus of the IAC to the geniculate ganglion (anterior genu). The nerve then turns posteriorly in its tympanic segment and, subsequently, turns vertically (posterior genu) to become the mastoid (descending) segment, exiting the skull base at the stylomastoid foramen. The vestibule, semicircular canals, and cochlea form the bony labyrinth (otic capsule) of the inner ear. The vestibule is a large ovoid perilymphatic space, which connects anteriorly to the cochlea and to the three semicircular canals: superior, lateral (horizontal), and posterior. The cochlea is shaped like a cone, with its apex pointing anteriorly, laterally, and slightly down, consisting of 2.5 to 2.75 turns. The cochlea is optimally visualized in its entirety on the Stenver reconstructed image (subsequently described). The membranous labyrinth is, by definition, the fluid-filled space within the bony labyrinth that is filled by endolymph (including the endolymphatic duct and sac) and perilymph (within the cochlear duct). CT of the temporal bone is usually performed with very thin sections (≤ 1.5 mm) and reformatted in Poschl (vestibular oblique view), Stenvers (cochlear oblique view), and standard axial and coronal planes, focusing on images reconstructed to display fine bony detail. Screening MR exams are performed with thin section (≤ 3 mm) technique, utilizing both the axial and coronal planes, with the strength of MR being depiction of soft tissue and fluid structures. The MR exam is typically supplemented with intravenous contrast injection, which is essential for evaluation of neoplastic disease, infection, and inflammation. For detail involving the temporal bone (and specifically the membranous labyrinth) as well as the adjacent CSF cisterns on MR, high resolution three-dimensional (3D) sequences, employing either constructive interference in the steady state (CISS) or fast spin-echo (FSE) techniques, are routinely acquired. At 3T images with a native isotropic resolution of ≤ 0.3 mm can be acquired in a clinically reasonable scan time. Fig. 2.6 Dehiscent jugular bulb. Thin section axial and coronal CT images of the temporal bone reveal focal dehiscence of the jugular plate with extension of a mass (part of the jugular bulb, arrow) into the hypotympanum. Congenital anomalies can involve the outer, middle, or inner ear. There can be stenosis or atresia of the external auditory canal. Dysplasia or aplasia can involve the middle or inner ear structures. Some malformations are known to be associated with meningitis, due to CSF leaks. The most common vascular variant is the dehiscent jugular bulb (Fig. 2.6). In this variant, which typically presents with pulsatile tinnitus, there is a dehiscent sigmoid (jugular) plate and the jugular bulb extends to lie within the inferior tympanic cavity. It will appear to clinicians as a “vascular” TM. A large vestibular aqueduct, caused by enlargement of the endolymphatic sac and duct, is the most common anomaly associated with pediatric congenital sensorineural hearing loss (Fig. 2.7). It is bilateral in 90% of patients and may be syndromic or nonsyndromic. The defining bony feature, as initially described, is enlargement of the vestibular aqueduct. There is a spectrum of associated cochlear and/or vestibular anomalies, ranging from subtle to gross dysmorphism. The most common specific features include modiolar deficiency and cochlear abnormalities. High-resolution T2-weighted MR (CISS or 3D FSE) is the imaging approach of choice, both for characterization and detection of associated anomalies. Dehiscence of the superior semicircular canal (SCC) (and much less commonly the posterior SCC) is being increasingly encountered. It is likely a developmental anomaly and patients typically present with Tullio phenomenon (sound-induced vertigo with or without nystagmus). Thin section, bone algorithm, high resolution temporal bone CT is used for evaluation, with Poschl reformatted images best to demonstrate this entity. Fig. 2.7 Large endolymphatic sac anomaly. The images presented include a thick section MIP of a 0.6-mm axial FIESTA-C (CISS) acquisition, a 3-mm axial FSE T2-weighted section, and a volume rendered view of the cochlea, vestibule, semicircular canals, and the large endolymphatic sac. The abnormality is bilateral in this instance (which is seen in 90% of cases). As evident on both T2-weighted exams (better evaluated on the left given the images presented), the cochlea (short arrow) is dysplastic, the vestibule (arrow) dilated, and the endolymphatic sac (*) large. Although better seen on CT (not shown), the vestibular aqueduct (which extends from the vestibule to the posterior surface of the petrous bone) was also noted to be enlarged on the thick section MIP. Inflammation and infection of the temporal bone can take on many different appearances. A middle ear effusion in an adult is important to recognize on both CT and MR, since eustachian tube obstruction, secondary to a nasopharynx neoplasm, must be excluded (Fig. 2.8). Mastoiditis on CT has a nonspecific appearance, with opacification of mastoid air cells. On MR, the air cells are opacified with debris that is of intermediate, not high, signal intensity on T2-weighted scans, with prominent contrast enhancement (Fig. 2.9). Complications associated with mastoiditis include sigmoid sinus thrombosis (with or without venous infarction), (Fig. 2.10) Bezold abscess (an abscess in the sternocleidomastoid muscle), and intraparenchymal/epidural abscesses (middle and/or posterior cranial fossae) (Figs. 2.11 and 2.12). In chronic mastoiditis on CT, there will be demineralization of trabeculae, with eventual formation of one large cavity (coalescent mastoiditis). The specific subclassifications and procedures for mastoidectomy are complex and varied, with the term itself referring to resection of mastoid air cells (Fig. 2.13). A mastoidectomy may be done to treat mastoiditis, chronic otitis media, or large cholesteatomas. Fig. 2.8 Nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC). Thin section axial images are illustrated at two levels, from a screening brain exam performed in a 52-year-old man with chronic headaches (left occipital in location). The upper image reveals fluid within both the mastoid air cells and the middle ear (*). The presence of the latter mandates a closer look at the exam for a possible cause. Although incidental mastoid air cell disease is common, fluid in the middle ear is not (and suggests obstruction and infection). Evaluation of the lower image reveals abnormal soft tissue (arrow) obliterating the opening of the eustachian tube (with mass effect upon the fossa of Rosenmüller), thus causing the effusions in the left middle ear and mastoid air cells. Biopsy revealed type III, undifferentiated, invasive NPC. Labyrinthitis refers to inflammatory disease of the inner ear (specifically the membranous labyrinth), which can be secondary to a middle ear infection or meningitis. Of all infectious agents, a viral etiology is most common, resulting from upper respiratory infection. In this instance, the disease is usually self-limited and imaging is not performed. In acute and subacute labyrinthitis, CT is normal and the only imaging finding (which is still not seen in most patients) is faint enhancement of the fluid on MR within the labyrinth. Chronic labyrinthitis consists of a fibrous stage followed by an ossific stage. In the fibrous stage there is loss of the normal high signal intensity within the fluid-filled labyrinth on T2-weighted scans. In the ossific stage diffuse or focal ossification of the normally fluid-filled spaces is seen on CT, with hypointense signal therein on T2-weighted MR (Fig. 2.14). Patients with typical Bell palsy (herpetic peripheral CN VII paralysis) do not undergo imaging. Atypical cases are often evaluated with MR, not for imaging of the facial nerve, per se, but to exclude underlying pathology such as tumor. Paralysis of the facial nerve is thought to occur from latent herpes simplex infection of the geniculate ganglion, and is typically unilateral. On MR, the nerve in Bell palsy will be normal in diameter (occasionally slightly enlarged) and display uniform, linear enhancement, most common in the fundal and labyrinthine segments but, occasionally, throughout its entire course (Fig. 2.15). Ramsey Hunt syndrome is caused by reactivation of a varicella zoster infection. As opposed to Bell palsy, however, it is typically associated with external ear vesicles, involvement of the entire intratemporal facial nerve and the vestibulocochlear nerve, with involvement of the membranous labyrinth (Fig. 2.16). Patients present with CN VII palsy and sensorineural hearing loss. Petrous apex lesions are varied and can be confusing. A cholesterol granuloma is the most common primary lesion of the petrous apex. This expansile lesion causes adjacent cortical thinning, and has distinctive high signal intensity on both T1- and T2-weighted images, the former due to the presence of hemorrhage and cholesterol. A cholesteatoma of the petrous apex (congenital or acquired) is less common but shares the characteristics of an expansile mass, with thinning and remodeling of adjacent bone. Its appearance on MR is, however, distinctive, consistent with its composition (an epidermoid), with low signal intensity on T1, high on T2, restricted diffusion, and no enhancement. Incidental lesions of the petrous apex that occasionally cause confusion include asymmetrical pneumatization and trapped fluid. The latter is common, and can be recognized by the presence of fluid with low T1 and high T2 signal intensity, without trabecular loss or any expansile nature (Fig. 2.17). Apical petrositis has a distinct appearance, consistent with infection, with prominent enhancement, including the adjacent meninges (Fig. 2.9). In the middle ear, the lesion of importance is the cholesteatoma. This lesion represents an enlarging mass of stratified squamous epithelium containing exfoliated keratin. The vast majority are acquired pars flaccida cholesteatomas. The appearance on CT is that of a soft tissue mass originating in Prussak space with erosion of the scutum and often filling the epitympanum (Fig. 2.18). Bony destruction is characteristic with larger lesions with erosion of the ossicles and Koerner’s septum (a bony septum extending medially and inferiorly into the antrum) being common. On MR, a cholesteatoma has low T1 and high T2 signal intensity and manifests restricted diffusion. MR is commonly performed in postoperative cases for differentiation, on the basis of diffusion-weighted images, of residual cholesteatoma from other lesions. Fig. 2.10 Mastoiditis with secondary transverse sinus thrombosis. On the T2-weighted scan in this pediatric patient, there is complete opacification of the right mastoid air cells, seen as intermediate signal intensity that is more typical of infection as opposed to simple fluid. Postcontrast, there is intense enhancement (black arrow), also consistent with infection. A met-hemoglobin clot (with high signal intensity on the precontrast T1-weighted image, white arrow) is seen occluding the right transverse sinus, a known serious complication of acute otomastoiditis. Fig. 2.12 Mastoiditis, with intracranial extension, the role of contrast enhancement. Sagittal postcontrast images from two different patients are presented, both demonstrating prominent enhancement of mastoid air cells consistent with infection. In the upper image, there is an ill-defined area of abnormal contrast enhancement (black arrow) in the adjacent temporal lobe, consistent with cerebritis. In the lower image, there is a mass lesion that exhibits a thin uniform enhancing rim (white arrow) and central necrosis, with extensive accompanying cerebral edema, in the adjacent temporal lobe, consistent with a brain abscess. Fig. 2.13 Mastoidectomy. An extensive resection of mastoid air cells has been performed in the distant past on the right, with the inner ear cavity preserved. Fig. 2.14 Labyrinthitis ossificans. (Part 1) Thin section axial CT images of the right and left temporal bones of a patient are presented, with the right inner ear normal. In chronic labyrinthitis, as illustrated on the patient’s left side, there is ossification of the fluid-filled spaces of the inner ear, which can be diffuse and profound. In this patient, the result is near complete obliteration of the cochlea (arrow). (Part 2) In a different patient, on axial thin section CISS images, there is diminished signal intensity within the cochlea, vestibule, and semicircular canals on the right, the MR presentation of chronic labyrinthitis ossificans (due to the normally fluid filled labyrinthine spaces becoming ossified). The term “otosclerosis” is actually a misnomer as the condition is actually “otospongiosis.” There is resorption of the normal endochondral bony otic capsule (of unknown cause), with deposition of new spongy vascular bone. Clinically, these patients present with conductive hearing loss and bilateral disease in 80%. The majority of cases are fenestral in location, and can involve just the oval window or both the oval and round windows. Retrofenestral (cochlear) otospongiosis, which is less common, can be patchy or diffuse, and can occur with or without fenestral involvement. On CT, in the active phase of the disease, there is demineralization and, in the chronic phase, sclerosis. Treatment for the associated hearing loss includes hearing aids, early in the disease course, and, later, stapedectomy. Fig. 2.16 Herpes zoster oticus (Ramsay Hunt syndrome). Abnormal enhancement is seen involving the intracanalicular and mastoid segments of the facial nerve on the left (white arrows). Enhancement of the entire course of the facial nerve was noted, including also the labyrinthine and tympanic segments (not shown). Fig. 2.17 Retained secretions, petrous apex. A nonexpansile lesion of the right petrous apex is identified, with fluid signal intensity precontrast (note the high signal intensity on FLAIR, *), and no abnormal enhancement. The lack of bone expansion differentiates this entity from other much less common lesions such as an epidermoid cyst or mucocele. Cochlear implants are common today, with surgery performed for both congenital and acquired deafness, but require the presence of a functioning cochlear nerve. The electrode array is placed into the scala tympani (one of the two perilymph-filled cavities of the cochlear labyrinth) in the basal turn of the cochlea (Fig. 2.19). Fig. 2.19 Cochlear implant. Thick section axial and coronal MIP, thin section axial, and lateral scout images from a CT exam reconstructed using a bone algorithm are presented. Both the electrode array, lying within the basal turn of the cochlea, and the receiver and stimulator, lying within the post-auricular soft tissues, are illustrated. Fig. 2.20 Longitudinal fracture, temporal bone. A fracture (arrows), parallel to the long axis of the petrous bone on the right, is seen on two axial sections. On the lower image, the mastoid air cells are noted to be opacified (compare with the normal left side), a clue in the setting of acute trauma to an underlying fracture. The fracture (small black arrows) traverses the mastoid air cells, with involvement of the facial nerve common in these fractures. Although temporal bone fractures were traditionally categorized relative to their orientation to the long axis of the petrous bone, as longitudinal or transverse, the majority of fractures are actually complex or oblique. If the traditional categorization is used, the more common fracture is the longitudinal fracture which is parallel to the long axis of the petrous bone (Fig. 2.20). Fractures can disrupt the ossicular chain, and transect either the cochlear nerve (with hearing loss) or facial nerve (with facial paralysis). CSF fistulas are not uncommon following a fracture involving the temporal bone. The most common neoplasm of the cerebellopontine angle is a vestibular schwannoma (arising from the vestibular division of CN VIII), which accounts for 10% of all intracranial tumors. Clinical symptoms consist of sensorineural hearing loss, tinnitus, and dysequilibrium. This benign, slow-growing, well delineated, encapsulated lesion typically arises within the internal auditory canal or (more commonly) is centered at the porus acusticus (Fig. 2.21). Growth rates are variable. The typical presentation today, due to improved access to medical care and advanced imaging (MR), is that of a small lesion within the IAC. Presentation as a large mass lesion causing compression of the brainstem is uncommon (Fig. 2.22). Although larger lesions can be seen on modern CT scanners, this modality does not play a clinical role in screening or diagnosis. Vestibular schwannomas on MR are intensely enhancing lesions, identified by their location and focal nature. The majority have both an intra- and an extra-canalicular component, with mild enlargement of the porus acusticus and with the extra-canalicular portion rounded in appearance. Very large lesions can have a cystic component. Up to one-third of vestibular schwannomas are purely intracanalicular, and, thus, are very small lesions (Fig. 2.23). For small to intermediate size lesions, stereotactic radiation is increasingly being recommended as the treatment of choice (Fig. 2.24). Although much less common, schwannomas of the cochlear and facial nerves do occur (Fig. 2.25). The latter can be, depending on extent, indistinguishable in appearance from a vestibular schwannoma. The differential diagnosis for a mass lesion at the cerebellopontine angle includes, in decreasing order of incidence, a (vestibular) schwannoma, meningioma, arachnoid cyst, and epidermoid. Fig. 2.22 Large vestibular schwannoma. A very large mass lesion widens and extends into the left internal auditory canal, with the bulk of the lesion extracanalicular in location. There is prominent deformity and displacement of the brainstem and fourth ventricle. There is little if any vasogenic edema. Vestibular schwannomas are, in general, very slow growing, and, if undetected, may result in large mass lesions such as that illustrated, with few symptoms (other than the loss of hearing) due to the ability to of the CNS to adapt well to slow chronic changes. Such lesions, common in the past, are rarely seen today due to more intensive screening and readily available medical care. Fig. 2.24 Stereotactic radiation therapy, vestibular schwannoma. One option for treatment of vestibular schwannomas is stereotactic radiation therapy. In the early months following radiation, central necrosis is observed, reflected on axial and coronal postcontrast scans by a central region of nonenhancement. With time, the lesion dimensions, overall, will regress. Meningiomas can occur in the cerebellopontine angle; however, as opposed to vestibular schwannomas, they are usually located eccentric to the porus acusticus. A meningioma should not enlarge the porus acusticus, and will only, uncommonly, extend into the internal auditory canal (Fig. 2.26). A broad-based lesion along a dural surface and calcification are common findings. Although a dural “tail” is a characteristic sign for a meningioma, this can also be seen with a vestibular schwannoma and is not a differentiating feature. Epidermoids are very slow growing lesions, and can reach substantial size prior to clinical presentation (usually as an adult). An epidermoid tends to insinuate itself into the cisterns, incorporating cranial nerves and vessels, and causing mild (and sometimes massive) irregular compression of adjacent brain. On CT epidermoid tumors will manifest as “dirty” CSF. On MR these lesions are near isointensity with CSF, being only slightly hyperintense on FLAIR, but with distinctive hyperintensity on diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI). A little appreciated caveat is that the high signal intensity (SI) of an epidermoid on DWI is not due to restricted diffusion, but, rather, to T2 shine-through (thus the apparent diffusion coefficient [ADC] map will not show the lesion to have lower diffusion as compared to adjacent brain). A trigeminal (CN V) schwannoma can arise anywhere along the course of the nerve, and, thus, can also occur at the cerebellopontine angle (CPA). A minority of trigeminal schwannomas in this location extend into both the middle and posterior fossae, having a dumbbell shape. The three major branches (ophthalmic, maxillary, and mandibular) of the trigeminal nerve exit the trigeminal ganglion (also known as the gasserian ganglion) which is located in the Meckel cave, with trigeminal schwannomas also rising in this location (Fig. 2.27). Trigeminal schwannomas are much less common than vestibular schwannomas, with the latter accounting for 95% of intracranial schwannomas. Facial nerve and cochlear schwannomas (Fig. 2.28) also occur, but are uncommon. The vast majority of CPA tumors are vestibular schwannomas (between 60 and 90%, in literature series), with other nonvestibular schwannomas much less common (4%). Head and neck paragangliomas occur in four common locations: in the tympanic cavity (glomus tympanicum paragangliomas [most common tumor of the middle ear]), at the skull base in the region of the jugular bulb (glomus jugulare paragangliomas [most common tumor of the jugular foramen]) (Fig. 2.29), in the high retrostyloid parapharyngeal (carotid) space (glomus vagale paragangliomas), and at the common carotid artery bifurcation (carotid body paragangliomas). The latter tumor classically splays the ICA and ECA and completely “fills” the carotid bifurcation (Fig. 2.30). Within the carotid sheath, glomus vagale paragangliomas displace the ICA anteriorly (as the vagus nerve is located posterior to the artery within the sheath) (Fig. 2.31). However, some large glomus vagale paragangliomas extend caudally and can also splay the internal and external carotid arteries, much like a carotid body paraganglioma. The classic, more specific, location of a glomus tympanicum paraganglioma is on the cochlear promontory (Fig. 2.32). This is the tumor known for its appearance as a red retrotympanic mass on otoscopic exam. One must be very careful to assess for presence of an aberrant internal carotid artery, which also presents with pulsatile tinnitus and a red retrotympanic mass. Look for integrity of the carotid canal wall. Large glomus tympanicum paragangliomas can fill the middle ear cavity (Fig. 2.33). Fig. 2.25 Facial nerve schwannoma. On axial thin section post-contrast T1-weighted scans (part 1) the facial nerve on the left is noted to be enlarged in diameter and enhancing, with involvement of the ganglionic, horizontal and vertical, segments (arrows). These findings are also well visualized on thin section postcontrast T1-weighted coronal scans (part 2). On thin section temporal bone CT, with both coronal and axial reformatted images (part 3), the facial nerve canal is noted to be enlarged (white * on coronal and black arrow on axial images) and to contain soft tissue. Paragangliomas, other than the glomus tympanicum paragangliomas, are typically smoothly contoured and ovoid in shape. Large tumors may be inhomogeneous, with areas of necrosis. On both T1- and T2-weighted images, the classic appearance is that of “salt and pepper,” with tiny areas of high signal intensity (salt) due to slow flow (or hemorrhage), and low signal intensity (pepper) due to fast flow (flow voids). Paragangliomas are hypervascular tumors, with early prominent enhancement. Digital subtraction angiography (DSA) reveals enlarged feeding arteries, and rapid venous drainage. Contrast enhancement on MR, in addition to providing lesion characterization (for all paragangliomas), assists in detection of small glomus tympanicum paragangliomas. However, this is typically not required as a noncontrast temporal bone CT is usually diagnostic (soft tissue mass on the cochlear promontory) and best to exclude a potential aberrant ICA. Bone destruction is common with glomus jugulare paragangliomas and is classically permeative-destructive. Glomus jugulare paragangliomas may also extend into the internal jugular vein. Although much less common, a schwannoma or meningioma can occur in the region of the jugular foramen, and should be kept in mind in terms of differential diagnosis. Fig. 2.27 Trigeminal schwannoma. (Part 1) A small, extraaxial, round, enhancing lesion (arrow) is seen on axial scans in the region of the Meckel cave. Note the chronic denervation fatty atrophy of the temporalis muscle on the right. Trigeminal schwannomas can involve multiple compartments—for example, both intracranial and the masticator space—and thus can be dumbbell in shape with a “waist” where it traverses the foramen ovale. (Part 2) The portion of the tumor (arrow) involving the cisternal segment of the nerve is seen on a coronal image, with the contralateral normal trigeminal nerve serving as a reference. Note also the atrophy of the right temporalis muscle, which is difficult to even visualize, in comparison to the normal left temporalis muscle (*). Fig. 2.29 Glomus jugulare paraganglioma. A mass involves the jugular bulb on the left, with intense enhancement postcontrast (arrow). Paragangliomas are hypervascular (thus their enhancement), with larger lesions also displaying a salt and pepper appearance on T1-and T2-weighted images. Fig. 2.30 Carotid body paraganglioma. At the bifurcation of the left common carotid artery, a large prominently enhancing mass (white arrow) is noted. The external and internal carotid artery branches are splayed by the mass, best seen on the axial thick MIP of the CTA (black arrow, common carotid artery). Fig. 2.32 Glomus tympanicum paraganglioma, CT. On axial and coronal reformatted images, a soft tissue mass (*) is noted along the medial wall of the left middle ear, abutting the cochlear promontory. Osteolytic areas are also noted in the temporal bone, posterior to the carotid artery, on the axial image. Addressing normal anatomy, the optic foramen (the opening of the optic canal) lies at the orbital apex and contains the optic nerve and the ophthalmic artery. The superior orbital fissure lies inferolateral to the optic canal and contains the oculomotor (CN III), trochlear (CN IV), and abducens (CN VI) nerves, together with the ophthalmic nerve (CN V1) (and branches therein) and the ophthalmic veins. The inferior orbital fissure lies more inferiorly, and slightly laterally, and contains the maxillary nerve (CN V2). The medial wall of the orbit is referred to as the lamina papyracea (paper thin). The extraocular muscles include the superior, inferior, medial, and lateral recti, together with the superior and inferior obliques and the levator palpebrae superioris. The superior oblique muscle is the longest and thinnest, passing anteriorly and medially through the trochlea and then turning posterolaterally and downward to insert on the lateral sclera. The inferior oblique, the only muscle not to originate from the orbital apex, originates from the maxilla. The levator palpebrae superioris muscle lies between the superior rectus muscle and the roof of the orbit, and may be difficult to separate from the superior rectus. The rectus muscles separate the intraconal space from the extraconal space. The lacrimal gland is located superolaterally in the orbit, with its vascular supply being the lacrimal artery. Tears produced by the lacrimal gland pass across the cornea and are absorbed through the lacrimal canaliculi of the upper and lower lids. In regard to innervation, CN III supplies the superior, inferior, and medial recti; the inferior oblique; and the levator palpebrae superioris muscles. CN IV supplies the superior oblique muscle and CN VI the lateral rectus muscle. Evaluation of the orbit by CT includes reformatted thin sections in all three primary planes, with intravenous contrast necessary for soft tissue evaluation and assessment of lesion vascularity. MR scans are also typically obtained in all three planes, with fat suppression essential for evaluation of orbital contents and the optic nerve. Intravenous contrast is routinely employed, in particular, for evaluation of mass lesions and the optic nerve. A few basic definitions are in order, in regard to orbital anomalies. In hypertelorism, the eyes (orbits) are farther apart than normal and, in hypotelorism, the eyes are abnormally too close. Exophthalmos (proptosis) is abnormal anterior protrusion of the globe. Orbital inflammation includes a number of diverse entities. Orbital cellulitis is divided into pre-septal and post-septal (orbital) types. In pre-septal cellulitis, infection is limited to the skin and subcutaneous tissues (Fig. 2.34). In post-septal cellulitis inflammation involves the orbital contents. In the textbooks, it is stated that most orbital cellulitis is secondary to paranasal sinus infection (most commonly from the adjacent ethmoid sinuses). Spread from sinus infection can result in a subperiosteal or orbital abscess (Fig. 2.35). This is usually treated as a surgical emergency. Cystic fibrosis is a predisposing condition. In severe cases of an orbital abscess there can be thrombosis of the ophthalmic veins and cavernous sinus. The term orbital pseudotumor refers to idiopathic orbital inflammation and is a diagnosis of exclusion. This entity is divided into subtypes, specifically anterior orbital inflammation, diffuse orbital pseudotumor, and orbital myositis (Fig. 2.36). Fig. 2.34 Pre-septal cellulitis. There is extensive left periorbital inflammation, pre-septal in location, without involvement of the contents of the orbit itself. This is to be differentiated from post-septal cellulitis, which is more commonly referred to as orbital cellulitis. There is increased thickness of the periorbital soft tissues on the left, with obliteration of normal fat planes, reflecting extensive soft tissue inflammation and edema. Although sinus infection can lead to pre-septal cellulitis, as in this patient, other etiologies including trauma are also common. In the anterior subtype, inflammation predominately involves the anterior orbit and globe. In the myositis sub-type, one or more of the extraocular muscles is primarily infiltrated and the tendons are typically involved. The differential diagnosis for the myositis subtype is thyroid orbitopathy. In thyroid associated orbitopathy, involvement of extraocular muscles is usually bilateral and symmetric (with accompanying exophthalmos). The most commonly involved muscles (in order of decreasing frequency) are the inferior, medial, superior, lateral, and oblique muscles (I’M SLO mnemonic). The enlargement of the muscles involves principally the bellies, sparing the tendons (Fig. 2.37). On CT there may be heterogeneous areas of lower density within the muscles. On MR typical findings include muscle edema in the acute phase and prominent enhancement of the involved muscles. Optic nerve gliomas histologically are low grade (i.e., pilocytic and fibrillary astrocytomas). Involvement can be limited to the nerve within the orbit, or can involve any portion of the visual pathway. Extension posteriorly from the orbit to involve the chiasm and optic tracts is not uncommon. Most optic nerve gliomas present in the first decade of life. There is fusiform enlargement of the optic nerve, often with proptosis (Fig. 2.38). Homogeneous enhancement is seen in some lesions, with no enhancement in others (Fig. 2.39). Optic nerve gliomas are associated with neurofibromatosis type 1 and, in this disease, can be bilateral. Intraorbital meningiomas can occur at the orbital apex, along the optic nerve (perioptic meningiomas), or unrelated to the nerve in the extraconal space. Meningiomas in the orbit are much more common in females and occur principally in middle-aged adults with painless, progressive visual loss and proptosis. When these occur in juvenile patients, they are usually associated with neurofibromatosis type 2. Linear (“tram-track”) or stippled calcifications are seen on CT in half of cases (Fig. 2.40). The term “tram-track” is also used to reference circumferential uniform enhancement along/around the nerve. As opposed to nerve enlargement in optic nerve gliomas, the optic nerve is normal in size with perioptic meningiomas (Fig. 2.41). Fig. 2.35 Subperiosteal abscess, orbit. An axial unenhanced CT, reconstructed with a soft tissue algorithm, demonstrates confluent density in the medial left orbit, extraconal in location. The ethmoid air cells are opacified bilaterally, of relevance to the diagnosis specifically on the left. A coronal reformatted image, from the same exam but reconstructed with a bone algorithm, demonstrates dehiscence (*) involving the lamina papyracea on the left. Sinusitis is the most common cause of a subperiosteal abscess involving the orbit. Fig. 2.37 Thyroid orbitopathy (Graves disease). Precontrast axial T1 and postcontrast T1 fat-saturated axial and coronal images are presented. All of the extraocular muscles are enlarged to some degree, and somewhat asymmetrically when comparing the left and right orbits. The enlargement predominantly involves the bellies of the respective muscles with sparing of the tendinous insertions. The lateral rectus muscles appear least involved. Fig. 2.38 Optic nerve glioma, neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1). In this 4-year-old child, there is fusiform enlargement of the right optic nerve, with characteristic kinking. As is common, in childhood NF1 cases, there is no abnormal enhancement. There is accompanying prominent dilatation of the optic nerve sheath (with increased fluid circumferential to the lesion). Common benign tumors of the orbit further include hemangiomas and lymphatic malformations, with schwannomas much less common. Capillary hemangiomas are seen in infants in the first year of life, most commonly located in the superior nasal quadrant. They typically grow rapidly for 1 to 2 years, regress over 3 to 5 years, and completely regress by late childhood (with proliferative, involuting, and involuted phases). A cavernous hemangioma, the most common intraconal vascular orbital tumor in adults, is seen most often in the second to fourth decades and appears as a well-defined, smoothly marginated, homogenous mass. It has a strong female predominance. Hemangiomas typically manifest patchy, central enhancement early and “fill-in” on delayed scanning (Fig. 2.42). A lymphatic malformation is an unencapsulated mass seen in children and young adults which is poorly circumscribed, multicystic, typically heterogeneous and may demonstrate characteristic fluid-fluid levels. Not infrequently, venous vascular elements are often present (venolymphatic malformation) (Fig. 2.43). A carotid cavernous fistula deserves mention in this section because it can present with proptosis. CT and MR typically demonstrate engorgement of the superior ophthalmic vein, which can be accompanied by enlargement of the extraocular muscles. Schwannomas of the orbit are rare, most common in the intraconal space and, on imaging, are sharply marginated and oval or fusiform in shape. Imaging features are those of other schwannomas in the head and neck. Most tumors of the lacrimal gland are benign, with benign mixed tumor (previously termed pleomorphic adenoma) most common. It is a well- encapsulated round lesion often producing scalloped remodeling of the lacrimal fossa. The most common malignant lacrimal gland tumor is adenoid cystic carcinoma. Lymphoma of the lacrimal gland may also be encountered, unilateral or bilateral, typically B-cell lymphoma.

Skull Base

Skull Base

Temporal Bone

Temporal Bone

Neoplasms

Orbit

Orbit

Inflammation/Infection

Neoplasms

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree