5 History taking and clinical examination

Psychiatric interviewing

The most important aims of psychiatric interviewing are (Institute of Psychiatry 1973):

In general, and particularly at the beginning of the interview, open questions (e.g. ‘How are you in your spirits?’) should be used in preference to closed questions (e.g. ‘Are you feeling low?’); it is important not to close off possible responses too soon. Indeed, it is often helpful to allow the patient to talk about his presenting problem for the first five minutes of the interview without being interrupted. In due course, when certain details in the history and mental state examination need to be established, the interviewer must set the agenda and can home in on the required details (see also Chapter 4).

Potentially violent patients

Rapport is increased and the risk of violence reduced if you sit about a metre away from the patient, at the same level and in a position where you can always look at him but he can look away. This is usually achieved by sitting at approximately right angles (see Figure 4.1). Both you and the patient should have free access to the door, so that he does not feel trapped and you can make an easy exit.

Psychiatric history

History of presenting illness

A chronological account of the development of each symptom should be given, together with any precipitating factors. Note any associated impairments. For example, for a depressive episode, biological and cognitive symptoms of depression (see Chapter 9) should be included. Note the effects of the patient’s condition on social functioning.

Personal history

Children

Details of any children should be given, including any disturbances from which they suffer.

Psychoactive substance use

Alcohol

Details should be obtained about the amount of alcohol the patient is currently drinking and the amount drunk in the past, including a history of any withdrawal symptoms (see Chapter 8). Also obtain any history of physical illnesses, injuries (e.g. road traffic accidents), legal problems (e.g. driving offences) or employment difficulties (e.g. being late regularly for work resulting in being sacked), as a result of alcohol intake. The CAGE Questionnaire (Chapter 7) should be routinely administered to patients to screen for alcohol problems; positive answers to two or more of the following four CAGE questions is indicative of problem drinking:

Mental state examination and descriptive psychopathology

Posture and movements

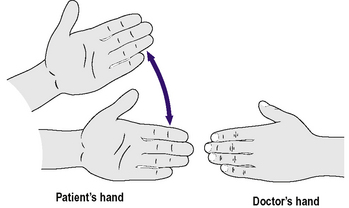

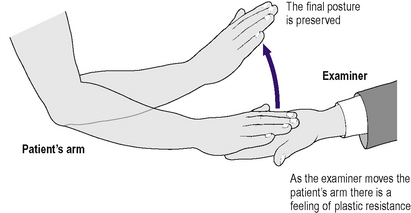

In schizophrenia, and sometimes also in other disorders, the following abnormal movements may occur: ambitendency, echopraxia, mannerisms, negativism, posturing and stereotypies. In ambitendency the patient makes a series of tentative incomplete movements when expected to carry out a voluntary action (Figure 5.1). Echopraxia is the automatic imitation by the patient of another person’s movements, which occurs even when the patient is asked to refrain. Mannerisms are repeated involuntary movements that appear to be goal directed. Negativism is a motiveless resistance to commands and to attempts to be moved. In posturing, the patient adopts an inappropriate or bizarre bodily posture continuously for a long time. Stereotypies are repeated regular fixed patterns of movement (or speech), which are not goal directed. In waxy flexibility (also called cerea flexibilitas), there is a feeling of plastic resistance as the examiner moves part of the patient’s body (resembling the bending of a soft wax rod) and that part then remains ‘moulded’ in the new position (Figure 5.2).

Tics are repeated irregular movements involving a muscle group and may be seen following encephalitis, in Huntington’s disease and in Gilles de la Tourette’s syndrome (see Chapter 16), for example.

Parkinsonism is associated with a festinant gait.

Overactivity

In psychomotor agitation there is overactivity, which is usually unproductive, and restlessness.

Social behaviour

Rapport

It is useful to record the nature of the rapport established with the patient. A positive rapport aids the formation of a constructive therapeutic relationship (see Chapter 4). A negative rapport may occur, for example, in the case of patients admitted to hospital against their will, and in some personality disorders (see Chapter 15). The rapport can be indicative of both the transference and the countertransference (see Chapter 4), and should be borne in mind when considering the underlying psychodynamics of the doctor’s relationship with the patient and the latter’s response to various types of treatment (such as individual psychotherapy). It is important that the doctor tries to establish a positive rapport.

Speech

Form of speech

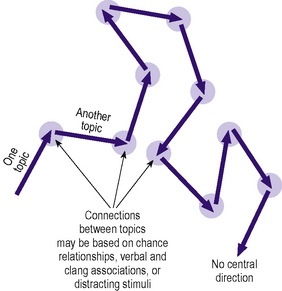

In flight of ideas, the speech consists of a stream of accelerated thoughts, with abrupt changes from topic to topic and no central direction (Figure 5.3). The connections between the thoughts may be based on:

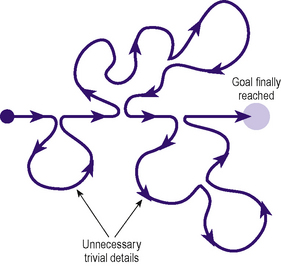

In circumstantiality, thinking appears slow, with the incorporation of unnecessary trivial details, but the goal of thought is finally reached (Figure 5.4).

Figure 5.4 • Diagrammatic representation of circumstantiality, showing how the goal of thought is finally reached.

The following five features of formal thought disorder were described by the psychiatrist Schneider:

Mood

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree