Chapter 97 Idiopathic Nightmares and Dream Disturbances Associated with Sleep–Wake Transitions

Abstract

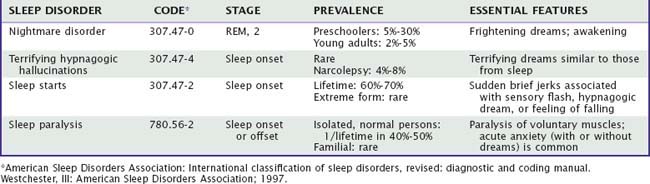

Because most common dreaming disturbances (Table 97-1) involve a perturbation of emotional expression during sleep, their study may help clarify the role of emotion in dream formation, dream function, and sleep mechanisms more generally. Physiologic evidence for emotional activity during rapid eye movement (REM) sleep is substantial. Autonomic system variability increases markedly in conjunction with central phasic activation,1 as seen especially in measures of cardiac function,2,3 respiration,4 and skin and muscle sympathetic nerve activity.5 Brain imaging, too, demonstrates increased metabolic activity in limbic and paralimbic regions during REM sleep,6 activity similar to that seen during strong emotion in the waking state.7 These dramatic autonomic fluctuations globally parallel dreamed emotional activity, which is detectable throughout most dreaming when appropriate probes are employed.8 Some studies indicate that most dreamed emotion is negative,9 primarily fearful,8 and may conform to a surgelike structure within REM episodes.10 Many theorists interpret the various forms of phasic activity occurring during sleep as indicating dream-related affective activity.11,12

Waking state emotional and cognitive reactions are also implicated in dream disturbances. For the most common disturbances, such as nightmares, dreamed emotions become unbearably intense, provoking an awakening that can lead to further distress, depressed mood, avoidance and coping behavior, and often even impairment of subsequent sleep. Perturbation of dream-related emotion can thus lead to a cycle of sleep disruption and avoidance, insomnia,13 and psychological distress that often leads the person to seek out professional help.14

However, causal relationships among emotion, dreaming, and other associated symptoms are not well understood. The emotional disruption inherent in nightmare disorder may be limited to sleep-related processes, in which case the dreaming process itself might be considered pathologic in some sense.15 However, the widespread belief that dreaming can serve an emotionally adaptive function (see Chapter 54) also suggests that some dream disturbances are adaptive reactions to more basic pathophysiologic factors rather than pathological per se.16

Idiopathic Nightmares

Historical Aspects

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM-IV)17 criteria for nightmare disorder (Table 97-2) have not changed substantially since the disorder was previously described as “dream anxiety disorder” in the DSM-III-R and “dream anxiety attack” in the DSM-III. The International Classification of Sleep Disorders, 2nd edition (ICSD-II) criteria for nightmares (see Table 97-2) have changed only slightly since the first edition (ICSD). Some new research on the phenomenology of nightmares has prompted a redefinition of the term nightmare in the more recent ICSD-II.

Table 97-2 Clinical Criteria for Nightmare Disorder

| CRITERIA | DSM-IV DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA FOR NIGHTMARE DISORDER (307.47) | ICSD-II DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA FOR NIGHTMARES (307.47-0) |

|---|---|---|

| Nature of recalled dream | Repeated awakenings from the major sleep period or naps with detailed recall of extended and extremely frightening dreams, usually involving threats to survival, security, or self-esteem. | Recurrent episodes of awakenings from sleep with recall of intensely disturbing dream mentation, usually involving fear or anxiety but also anger, sadness, disgust, and other dysphoric emotions. |

| Nature of awakening | On awakening from the frightening dreams, the person rapidly becomes oriented and alert (in contrast to the confusion and disorientation seen in sleep terror disorder and some forms of epilepsy). | Alertness is full immediately on awakening, with little confusion or disorientation. |

| Nature of distress | The dream experience, or the sleep disturbance resulting from the awakening, causes clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of function. | |

| Timing | The awakenings generally occur during the second half of the sleep period. | The episodes typically occur in the latter half of the habitual sleep period. |

| Differential diagnosis | The nightmares do not occur exclusively during the course of another mental disorder (e.g., a delirium, posttraumatic stress disorder) and are not due to the direct physiologic effects of a substance (e.g., a drug of abuse, a medication) or a general medical condition. | Nightmares are distinguished from several other disorders in a Differential Diagnosis section: seizure disorder, arousal disorders (sleep terrors, confusional arousal), REM sleep behavior disorder, isolated sleep paralysis, nocturnal panic, posttraumatic stress disorder, acute stress disorder. |

The widely accepted definition of a nightmare has long been “a frightening dream that awakens the sleeper,” but researchers have come to reevaluate these defining features. Some18 argue that the “awakening” criterion should indeed designate nightmares but that disturbing dreams that do not awaken (“bad dreams”) should nevertheless be considered clinically significant. Whether or not the person awakens presumably reflects a dream’s emotional severity, but it is not the only index of severity. First, among patients with various psychosomatic disorders, even the most macabre and threatening dreams do not necessarily produce awakenings.19 Second, less than one fourth of patients with chronic nightmares report “always” awakening from their nightmares, and these awakenings do not correlate with either nightmare intensity or psychological distress.13 Third, among subjects with both nightmares and bad dreams, approximately 45% of bad dreams are rated on a level of emotional intensity that is equal to or exceeds that of the average nightmare.20 In short, whereas disturbing dreams often can awaken a sleeper, awakenings are not the sole or even the best index of the severity of the disorder.

Similarly, researchers have come to define nightmares more inclusively with respect to their emotional tone. This is reflected in the modified ICSD-II definition of nightmares as “disturbing mental experiences” rather than as “frightening dreams” as in the ICSD. Although fear remains the most commonly reported nightmare emotion,20 some argue18 that nightmares can involve any unpleasant emotion. However, distressing dreams related to bereavement are considered by some as constituting a distinct nosologic entity known as existential dreams.21

Prevalence and Frequency

Lifetime prevalence for a nightmare experience in the general population is unknown but may well approach 100%. If we consider only dreams of attack and the pursuit theme, which are the most common nightmare themes, the lifetime prevalence varies from 67%22 to 90%.23 Pursuit alone has a lifetime prevalence of 92% among women and 85% among men.23

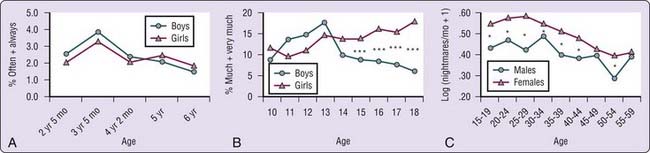

An ensemble of population studies indicates that the prevalence and frequency of nightmares increases through childhood into adolescence, when a marked gender difference takes hold (Fig. 97-1). Preschoolers report bad dreams surprisingly seldom. From 1.3% to 3.9% of parents report that their children have them “often” or “always” and there is no gender difference at this age (see Fig. 97-1A).24 Subsequently, as shown in a study of 6727 Kuwaiti 10- to 18-year-old children,25 nightmare prevalence increases from ages 10 to 13 years for both boys and girls and thereafter continues to increase for girls but decreases progressively for boys (see Fig. 97-1B). This finding replicates with more precision our finding that boys and girls aged 13 years report bad dreams often with about equal prevalence (boys, 2.5%; girls, 2.7%), whereas at age 16 years prevalence for the same children diverges markedly (boys, 0.4%; girls, 4.9%).26 The gender difference is then maintained into adulthood and old age, even though the prevalence of nightmares decreases steadily over time for both men and women (see Fig. 97-1C).27

Figure 97-1 Nightmare prevalence over the lifespan. A, Proportion of preschool children having bad dreams “often” or “always” as reported by parents in a longitudinal study (girls: n = 490-493; boys: n = 468-477).24 No sex difference is apparent at any age. B, Proportion of children and adolescents having nightmares “much” or “very much” in the last month (girls: n = 3372, mean age = 14.1 ± 2.05 years; boys: n = 3355; mean age = 14.0 ± 2.12) (***P < .0001)25; C, log(number of nightmares in a typical month + 1) reported by respondents to an Internet questionnaire (female: n = 19,367, mean age = 24.9 ± 10.14 years; male: n = 4,623; mean age = 25.5 ± 10.81) (*P < .05).

(From Nielsen TA, Petit D. Description of parasomnias. In Kushida CA, editor. Handbook of sleep disorders. Oxford: Taylor and Francis; 2008. p. 459-479.)

This general profile of age and gender differences is consistent with a large corpus of research for young children,28 adolescents,26 young adults,29 middle-aged adults,30 and the general population.31 Slightly different patterns have been reported for some pediatric32 and elementary school33 samples, however.

Nightmare prevalence may be elevated in clinical populations. For example, 25% of chronic alcoholics and drug users report nightmares “every few nights” on the Minnesota Multiphasic Inventory (MMPI),34 and 66% of suicide attempters report moderate or severe nightmares.35 However, other findings of elevated prevalence are difficult to assess because a frequency criterion is not specified; for example, approximately 24% of nonpsychotic patients seen in psychiatric emergency services report nightmares, but with an unknown frequency.36

When compared to results from daily home logs, however, retrospective self-reports underestimate current nightmare frequency by a factor of 2.5 in young adults18 to a factor of more than 10 in the healthy elderly.37 In general, a 1-month retrospective estimate is closer to the estimate provided by daily logs than is a 12-month retrospective estimate and is thus the preferred standard for retrospective assessment. Because nightmare prevalence and frequency are seriously underestimated by retrospective instruments, daily logs are the method of choice.

Familial Pattern

Twin-based studies have identified persistent genetic effects on the disposition to nightmares in childhood, as reported retrospectively by adults, and in adulthood,30a as well as genetic influences on the co-occurrence of nightmares and some other parasomnias, such as sleeptalking, but not others, such as bruxism.38 In the Finnish twin cohort study, a genetic basis for nightmares was shown in the proportion of phenotypic variance in trait liability for nightmare prevalence attributable to genetic influences at about 45%.30 A second study reports a 51% genetic influence.30a

Pathophysiology

One laboratory study of nightmares39 indicates moderate arousal—increased heart and respiration rates—during some nightmare episodes, but unexpectedly low arousal in most others. These early findings constitute the principal empirical basis for diagnostic guidelines such as the ICSD and DSM-IV, but there are serious problems with the work, such as the inclusion of psychiatric patients and patients with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in the study sample.

Recordings of heart rate and respiration rate during nightmare and non nightmare REM sleep episodes confirmed a moderate level of sympathetic arousal during nightmares.40 Mean heart rate for nightmare sleep was elevated (by about 6 bpm) for the 3 minutes before awakening. Mean respiration rate was only marginally higher at this time. We have recorded higher absolute and relative alpha power over primarily right posterior sites in the last 2 minutes of nightmare sleep. However, these changes might reflect processes of awakening.

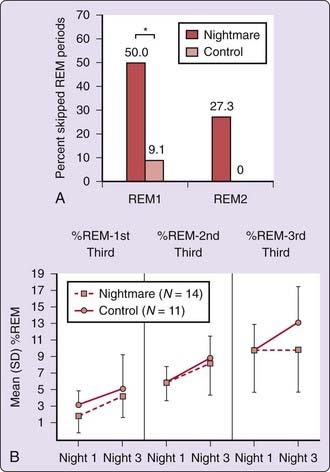

The typical sleep of nightmare subjects does not differ dramatically from that of paired controls41; although elevated levels of periodic limb movements in sleep (PLMS) have been observed for both idiopathic and PTSD nightmare sufferers.42 REM sleep measures suggest that nightmare subjects have abnormally low REM sleep propensity, even during recovery sleep following partial REM sleep deprivation in a 3-night protocol (Fig. 97-2).41

Personality

Although many studies report relationships between nightmare frequency and measures of psychopathology,18,26 some do not.43 Several detailed reviews are available.14,44,45 Inconsistent relationships between nightmares and psychopathology likely reflect mediating factors, among which three—nightmare chronicity, nightmare distress, and coping style—are reviewed below.

Nightmare Chronicity

Adults with a lifelong history of frequent nightmares compose an idiopathic nightmare subgroup with more psychopathologic symptoms than matched controls, such as higher neuroticism and MMPI scores.46 However, Hartmann47 found that no one measure of psychopathology adequately describes these persons. He proposed48 a general “boundary permeability” personality dimension, correlated with nightmare prevalence,49 which, at one extreme (thin boundaries) characterizes lifelong sufferers who are more open, sensitive, and vulnerable to intrusions than thick-boundary subjects, including a greater sensitivity to events not usually viewed as traumatic.47

Nightmare Distress

Nightmare frequency and waking distress over one’s nightmares are only moderately correlated measures in adults50 and largely unrelated in adolescents.51 Subjects might have only few nightmares (e.g., one per month) yet report high levels of associated distress and vice versa. It is nightmare distress, not necessarily nightmare frequency, that is significantly related to psychopathology, especially to measures of anxiety and depression.52 Thus, nightmare-induced distress might simply be an expression of a more general distress style.14 However, even though both state (stress) and trait personality measures correlate with nightmare frequency, trait measures do not account for any variance beyond that accounted for by state measures.53 Nightmare distress should be evaluated during clinical intake because, although it is not among the diagnostic criteria of the DSM-IV or ICSD-II, it is central to defining nightmares as a clinical problem.

Coping Style

Given the central role of nightmare distress, a person’s ability to cope with stress may be pivotal in whether a clinical problem with nightmares develops. Dysfunctional coping strategies such as dissociation might exacerbate both nightmare distress and chronicity. College students with nightmares report both higher rates of childhood trauma and higher scores on dissociative coping (Dissociative Experiences Scale, DES) than do students without nightmares.54 Adaptive and maladaptive coping strategies may come into play at a very young age because dissociation scores on the Child Dissociative Checklist are associated with nightmares among children as young as 3 to 4 years.55

Effects of Drugs and Alcohol

Numerous classes of drugs trigger nightmares and bizarre dreams, including catecholaminergic agents, beta-blockers, some antidepressants, barbiturates, and alcohol. One review56 suggests that the therapies most often associated with nightmares are sedative/hypnotics, beta-blockers, and amphetamines and that REM suppression is a frequent mechanism of action. Among catecholaminergic agents, reserpine, thioridazine, and levodopa are all occasionally associated with vivid dreams and nightmares,57–59 as are beta-blockers such as betaxolol, metropolol, bisoprolol, and propranolol.60–62 Among the antidepressants, bupropion leads to more vivid dreams and nightmares than do other antidepressants.63 The selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) paroxetine and fluvoxamine suppress dream recall frequency while simultaneously increasing subjective dream intensity and bizarreness, possibly due to serotoninergic REM suppression.64 Bedtime administration of tricyclic and neuroleptic agents leads to a higher recall of frightening dreams than when these are taken in two daily doses,65 even though normal dream recall frequency remains the same. Neuroleptics and tricyclics appear to render dream affect more dysphoric rather than to increase dream recall per se.

Withdrawal from barbiturates is associated with REM rebound, vivid dreaming, and nightmares.66 A hypothesis has been advanced that barbiturate suppression of REM sleep, much like with alcohol, causes REM sleep rebound after discontinuation of the drug and consequently longer and more vivid dreams.67 In addition, several case studies have alerted physicians to the nightmare-causing effects of specific substances (Table 97-3). Evening, but not morning, doses of the acetylcholinesterase inhibitor donepezil induces nightmares.68 The antimalarial drug mefloquine produces vivid dreams and nightmares.69

Table 97-3 Drugs Reported in Case Studies to Increase Frequency of Nightmares

| DRUG | FUNCTION | REFERENCE |

|---|---|---|

| Betaxolol | Beta-blocker | Mort, 1992126 |

| Carbachol | Cholinergic agent | Mort, 1992126 |

| Donepizil | Cholinesterase inhibitor | Ross and Shua-Haim, 1998127 |

| Erythromycin | Antibiotic | Black and Dawson, 1988133 |

| Fluoxetine | Antidepressant | Lepkifker, Dannon, Iancu, et al, 1995128 |

| Naproxen | Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory | Bakth and Miller, 1991129 |

| Nitrazepam | Benzodiazepine hypnotic | Girwood, 1973132 |

| Thiothixene | Neuroleptic | Solomon, 1983125 |

| Triazolam | Benzodiazepine hypnotic | Forman and Souney, 1989131 |

| Verapamil | Antimigraine agent | Kumar and Hodges, 1988130 |

Sleep and dream disturbances follow alcohol withdrawal. Alcoholic patients report more vivid dreams and nightmares following withdrawal than they do during ingestion; although these are more frequent in the week following withdrawal, they are still present in subsequent weeks. The nightmares and insomnia of withdrawal can lead to resumed drinking in an attempt to normalize sleep. In fact, 29% of a group of 100 alcoholics reported further drinking to alleviate nightmares.70 This relationship is also of critical importance because of the danger of alcohol self-medication for PTSD71 and other nightmare-producing disorders.

Vivid and macabre dreaming may be central to the delirium tremens (DTs) of acute alcohol withdrawal.72 Because alcohol suppresses REM sleep, and because REM percentage (particularly at sleep onset) is extremely elevated in patients with DTs,73 a theory of DT hallucinations emphasizing REM rebound and intrusion of dreaming into wakefulness has been proposed.74 Case studies strongly suggest that hallucinations may seem to continue uninterrupted from an ongoing nightmare.75 DT sleep appears to be a mixture of REM sleep with “stage 1 REM sleep with tonic EMG,” which distinguishes it from the sleep of alcoholics without DTs.76 Some have failed to observe this pattern, however.77 The similarity of sleep patients with DTs to those with REM sleep behavior disorder (RBD) has also been noted.78

Acute withdrawal from cocaine often induces unpleasant dreams.79 Strange dreams, including nightmares, are one of the most consistently reported effects of withdrawal from cannabis; they are persistent, lasting for longer than 45 days after withdrawal.80 In two studies, strange dreams are rated to be “severe” and “moderate” by 20% and 37% of adults and by 8% and 15% of adolescents seeking treatment.81,82

The neuropharmacologic bases of drug-induced or withdrawal-associated disturbed dreaming remain unclear. There may be a balance among various neurotransmitter systems such that nightmares are produced by reduced brain norepinephrine and serotonin or increased dopamine and acetylcholine.47 REM suppression is implicated as a mechanism in the action of many agents (e.g., beta-blockers), as is dopamine receptor stimulation.56 Dissociation of dream initiation and intensification processes by separate neuromodulatory systems may also be implicated64 (see Chapter 48).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree