Indications for Treatment

John M. Freeman

Timothy A. Pedley

Introduction

Epileptic seizures are among the most common symptoms of disturbed brain function. They result from many causes and can have widely varying manifestations. An epileptic seizure (a discrete event resulting from transient, hypersynchronous, abnormal neuronal behavior) should be distinguished from epilepsy (the condition of recurring epileptic seizures). Seizures are epileptic events and the indispensable characteristic of epilepsy, but not all seizures are manifestations of epilepsy. There are many different types of seizures, each producing a profile of characteristic behavioral changes and electrophysiologic disturbances. Some patients have seizures that are self-limited—that is, they occur only in the course of an acute medical or neurologic illness. Other people have one or two single seizures at some time in their life for which a cause is never determined. Such seizures are not epilepsy. Epilepsy, on the other hand, is a group of chronic disorders, the hallmark of which is recurrent, unprovoked seizures. Many patients with epilepsy have more than one seizure type, and many have other symptoms as well. Sometimes, additional electroencephalographic (EEG), clinical, familial, etiologic, and prognostic data are sufficiently similar among a group of patients with epilepsy that a more specific epileptic syndrome can be defined.

Given these considerations, it should not be surprising that the many seizure types and the various forms of epilepsy have different etiologies, different prognoses, and different consequences, each of which may have quite different implications for individual patients. Thus, indications for treatment also vary, and no formula or algorithm can be applied justifiably to all cases.

The nature and severity of the consequences of seizures depend on the type and timing of attacks, the age and condition of the affected individual, the patient’s type of employment, the response of the patient’s family, societal attitudes, and many other factors. Because the effects of seizure recurrence are so variable, each affected person must be considered uniquely during evaluation of the impact of further seizures in relation to the potential consequences—both beneficial and adverse—of treatment. Ultimately, the decision regarding whether to treat rests with the patient or, in the case of young children, the patient’s family. This is as it should be because only the individual affected by seizures, and the family, can determine the extent to which further seizures will interfere with that individual’s life. It is therefore the patient’s perception of the consequences of further seizures that drives the decision to treat or not to treat.

Illustrative Cases

Case 1. Should a 2-year-old girl who has had a single convulsion lasting <2 minutes associated with a fever of 101°F be started on drug treatment? What if the seizure had lasted 20 minutes? What if the child had had a second brief seizure 24 hours after the first? Or another seizure 6 months later?

Case 2. Should a 14-year-old boy be started on drug treatment after a first unprovoked generalized tonic–clonic seizure? Would it make a difference if he were 17 years old and driving?

Case 3. Should antiepileptic drug therapy be recommended to a recently married woman whose husband first noted her early-morning “jumps” and then witnessed a generalized tonic–clonic seizure? Would the advice be different if she were eager to start a family?

Case 4. Should a 3-year-old girl with profound retardation who has been having two staring spells each week for the last several months be started on drug treatment? What if she were having drop attacks instead? Would the physician’s advice depend on whether the child was ambulatory? At home or in a long-term care facility?

Case 5. How would a physician advise a factory worker who has had a first nocturnal generalized tonic–clonic seizure? Would the physician’s advice be different if the patient expressed concern about failing the plant’s required random drug screens and possible job loss after starting drug treatment? Would the physician’s recommendations be influenced if the patient used heavy industrial power tools? Or drove a truck? Would the recommendations be the same for a housewife?

Each of these cases emphasizes situations that are unique to a particular patient and illustrates that both the consequences of further seizures and the consequences of treatment can be quite different, depending on individual circumstances. This chapter reviews the factors that physicians should consider in assisting patients and their families to reach informed, reasonable decisions about whether to initiate treatment.

Elements of the Decision-Making Process: Assessing Risks and Benefits

Type of Seizure

It is obvious that different seizure types have different consequences for patients. A generalized tonic–clonic seizure is likely to be far more hazardous and have more psychosocial impact than an absence seizure. A typical simple partial seizure of benign rolandic epilepsy, manifested only by speech arrest, salivation, and facial twitching, may be much less important to an individual than a complex partial seizure with unresponsiveness, prominent automatisms, and postictal confusion. An atonic seizure that causes a child to fall, with risk for injury, can be very debilitating, even though brief. Complex partial seizures that begin with a prolonged aura are usually less

disabling than complex partial seizures that begin with abrupt loss of consciousness. Different epilepsy syndromes, with different seizure types and prognoses, are likely to affect patients in very different ways.

disabling than complex partial seizures that begin with abrupt loss of consciousness. Different epilepsy syndromes, with different seizure types and prognoses, are likely to affect patients in very different ways.

Timing of Seizures

Some persons have only nighttime seizures. Others have seizures only in the morning after awakening. Some women have seizures linked to phases of their menstrual cycles. Other patients have seizures only in certain circumstances (e.g., when deprived of sleep, when under great stress, or after drinking) or with specific triggers (reflex epilepsies). Many patients have seizures that are completely unpredictable. The temporal patterns of seizures clearly influence their impact on patients’ lives.

Frequency of Seizures

Only about 30% of persons who have a single, unprovoked, generalized tonic–clonic seizure have a second, regardless of whether they are treated. Many children with benign epilepsy syndromes have only a few seizures. Patients with cryptogenic or symptomatic localization–related epilepsy usually have frequent seizures that may be drug resistant. Individuals with temporal lobe epilepsy typically have many complex partial seizures but relatively infrequent secondarily generalized seizures. Someone with frontal lobe epilepsy, however, may have mainly generalized seizures.

Frequent seizures of whatever type interfere with function, but the responses of individuals, even to daily or weekly seizures, vary widely. Some patients are greatly disabled; they are socially isolated, unemployed, and severely restricted in what they can do. Others with similar seizures are gainfully employed, well adjusted, and productive members of society. Children generally adapt better to a higher rate of seizures than do adults. Thus, although frequency of seizures is closely related to the consequences of epilepsy, the impact varies among individuals, even those with the same rate of seizures, depending on many factors—intrinsic and acquired; personal and societal—that affect a person’s support mechanisms and ability to cope and adapt.

Effects of Age on Consequences of Seizures

The consequences of recurrent seizures are age dependent. Infants, whatever the seizure type, are unlikely to be physically injured during a seizure or even be aware, or remember, that a seizure has occurred. Toddlers, although usually in a supervised environment, are more likely to be affected by consequences related to the seizures, but these depend greatly on the type of seizure (e.g., head injury from an atonic seizure). In addition, children begin to feel the effects of overprotection resulting from the family’s fear of recurrence. Adolescents, with their desire to conform, sensitivity to embarrassment, and growing desire for independence, are greatly affected by recurrent seizures. Common concerns include loss of control of bodily functions, especially incontinence; not being able to obtain a driver’s license or, if they are already driving when seizures begin, loss of the license; social isolation; and conflicts about restrictions—both reasonable and unreasonable—imposed by parents, schools, and sports teams. Adults face restrictions on driving (which may, in some cases, directly affect livelihood); employment (keeping a job or having opportunities for career advancement); and social opportunities, including the ability to develop and maintain significant relationships. Adults are also concerned that they may be unable to meet their responsibilities as parents or providers, and they naturally fear embarrassment.

Environment

The consequences of seizure recurrence at each age may also vary according to whether the patient lives in a city, where medical facilities are generally close by and easily accessible via public transportation, or in a rural environment, where medical services and community resources are limited and often distant, close neighbors are few, and personal automobiles are the only means of transportation.

Consequences of seizures also depend on occupation. For any given seizure type or frequency, the consequences for office workers will likely be different than for persons operating machinery, and individuals who must work in exposed areas face different consequences than those who work in protected environments.

Consequences of Treatment

Consequences of treatment depend on the drug chosen and the number of drugs used. They also depend on whether side effects develop and whether seizures are completely or only partially controlled. All drugs have adverse effects, some more than others, and these range from minor to severe. Neurotoxicity can be subtle, especially in terms of effects on cognition and behavior. Children especially may inadvertently be overtreated, with adverse consequences for learning and psychological development.

Deciding Whether to Treat

The Issue

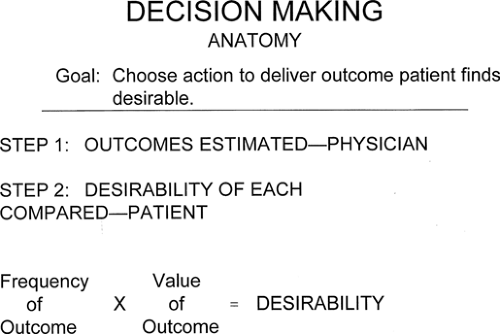

Although there can be little doubt that drug treatment is indicated and beneficial for most patients with epilepsy, there are certain circumstances in which antiepileptic drugs may reasonably be withheld or deferred or used for only a limited time. The common issues in such cases are those listed in the foregoing section and relate to (a) the probability of seizure recurrence, (b) the likelihood of substantial psychosocial, vocational, or physical consequences with further seizures, and (c) the question of whether the benefit to be derived from treatment substantially outweighs the chance of treatment-related side effects (Fig. 1).

Acute Symptomatic Seizures

Acute symptomatic seizures are those caused or provoked by an acute medical or neurologic illness. Febrile seizures in children are the most common example (see Chapter 57). Other frequently encountered causes include metabolic or toxic encephalopathies (uremia, hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia, hepatic failure, drug withdrawal) and acute brain infections (encephalitis, meningitis). To the extent that there is no underlying permanent brain damage, seizures occurring in these settings are usually self-limited. The primary therapeutic consideration in such patients should be identification and treatment of the underlying disorder. If antiepileptic drugs are used to suppress seizures acutely, they generally do not need to be continued after the patient has recovered from the primary illness. It is important to remember, however, that the presence of a precipitating medical illness does not necessarily exclude the

need to search for brain pathology; underlying brain lesions increase the risk for acute symptomatic seizures (as well as epilepsy) in appropriate settings.7

need to search for brain pathology; underlying brain lesions increase the risk for acute symptomatic seizures (as well as epilepsy) in appropriate settings.7

The issue of treating acute symptomatic seizures that occur in the setting of stroke, head injury, neurosurgical procedures, and alcohol use is more complicated. Each of these is a significant risk factor for both acute symptomatic seizures and epilepsy.8 Although antiepileptic drugs are effective in treating seizures acutely, none has yet been shown to delay or reduce the development of later epilepsy. This has been best demonstrated for seizures occurring after a head injury (see Chapter 253). Phenytoin, for example, is highly effective in suppressing seizures in the first week after a head injury, but long-term prophylactic treatment is ineffective in preventing posttraumatic epilepsy.22 The association between alcohol and seizures is also complicated. Whereas acute alcohol withdrawal can trigger self-limited seizures that do not require treatment, chronic alcoholism is a major risk factor for epilepsy.14 Thus, over time, many alcoholics may have both acute symptomatic seizures (withdrawal seizures) and recurrent unprovoked seizures (epilepsy).11,20 Given these considerations, we believe that the approach to patients who have acute symptomatic seizures as well as a substantially increased risk for later epilepsy should be based on the need to suppress active seizures, not on the hope that later epilepsy may be prevented.17 This approach is supported not only by clinical experience and the results of a limited number of clinical trials, but also by results of animal experiments investigating the mechanisms of action of antiepileptic drugs now available. For the most part, current antiepileptic drugs, although effective as seizure suppressants, do not affect the development of epilepsy (epileptogenesis).19

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree