Seizures

ISs involve a sudden, generally bilateral and symmetric contraction of the muscles of the neck, trunk, and extremities. The type of seizure that occurs depends on what muscles (the flexor or extensor) are predominantly affected and on the extent of the contraction.

Flexor spasms have long been regarded as the most characteristic type of seizure, and thus, they have been predominantly featured in naming the syndrome (

syndrome des spasmes en flexion,

jackknife convulsions,

salaam seizures,

Grusskrämpfe). They consist of a sudden flexion of the head, trunk, and legs, which are usually held in adduction. The arms, also in flexion, can be adducted or abducted. In three studies (

Lombroso, 1983a;

Kellaway et al., 1983;

Lacy and Penry, 1976), flexor spasms represented 34%, 39%, and 42%, respectively, of the cases. Mixed flexor-extensor spasms, accounting for 42%, 47%, and 50% of the cases, were the most common type. These consist either of flexion of the neck, trunk, and arms with extension of the legs or, less commonly, of flexion of the legs and extension of the arms with varying degrees of flexion of the neck and trunk.

Extensor spasms, which involve an abrupt extension of the neck and trunk accompanied by extension and abduction of the arms, are less common (23%, 24%, and 19%, respectively); only rarely do they represent the sole type of seizure in any particular infant (

Lombroso, 1983b;

Jeavons and Bower, 1974). Most infants with ISs have more than one type of spasm.

The intensity of the contractions and the number of muscle groups involved vary considerably both in different infants and in the same infant with different attacks. The spasms may consist of only slight head nodding, upward eye deviation, or elevation and adduction of the shoulders in a shrugging movement. In some cases, the spasms may be so slight that they can be felt but not seen, or they may be clinically unnoticeable, even though they do appear on polygraphic recordings (

Kellaway et al., 1979,

1983;

Gastaut et al., 1964). The number of spasms is vastly in excess of what parents record in these infants (

Kellaway et al., 1979;

Gaily et al., 2001). No apparent correlation exists between the overall prognosis and intensity of the spasms, although full-fledged attacks may tend to occur in cryptogenic cases (

Dulac et al., 1986a). According to

Kellaway et al. (1979), the muscle action tracing in an IS consists of an abrupt initial contraction lasting less than 2 seconds, followed by a more

sustained contraction lasting 2 to 10 seconds. The second, or tonic, phase may be absent, with the spasm, in these cases, being limited to an initial phasic contraction lasting 0.5 seconds or less. The contraction may have a diamond shape on electromyographic records (

Fusco and Vigevano, 1993;

Egli et al., 1985). A cry is common at the time of, or just after, the spasm. Spasms are often followed by a brief episode of akinesia and diminished responsiveness that is termed

arrest; this may also occur in the absence of a spasm (

Donat, 1992;

Lombroso, 1983b;

Kellaway et al., 1979).

In 6% to 8% of patients (

Lombroso, 1983a;

Kellaway et al., 1979), the spasms may be unilateral, often with an adversive element, or they can be clearly asymmetric. Asymmetric spasms are associated with a symptomatic etiology; unilateral lesions, however, are often associated with symmetric attacks.

Lateralized motor phenomena, including eye deviation, lateral upward eye deviation, eyebrow contraction, and abduction of one shoulder, may sometimes constitute the entire series of spasms, or they may initiate a series that eventually develops into bilateral phenomena. Such lateralized manifestations are usually accompanied by unilateral or asymmetric ictal EEG changes.

Individual spasms are grouped characteristically in series or clusters. The clusters can include as little as a few units to more than 100 individual jerks occurring from 5 to 30 seconds apart. The intensity of the jerks in a series may initially wax and wane, although not always regularly. Rare cases of status of ISs have been reported (

Coulter, 1986). The repetitive character of the spasms is a highly important diagnostic clue. In a young infant, even very mild or atypical phenomena (e.g., head nodding, eye elevation, and movement of one limb) occurring repetitively should arouse the suspicion of ISs.

Brief interruptions of consciousness probably occur at the time of the jerks. Respiratory irregularities; crying at the end of a cluster; flushing; abnormal eye movements, such as nystagmus or tonic upward or lateral eye deviation; smiling; or grimacing are observed in one-third to one-half of the attacks. Laughter is occasionally noted (

Matsumoto et al., 1981a;

Fukuyama, 1960;

Druckman and Chao, 1955). The number of series can vary from only 1 to 50 or more daily (

Lacy and Penry, 1976;

Jeavons and Bower, 1964). Clusters may occur during sleep, usually at the time of awakening or during the transition from slow to rapid eye movement (REM) sleep (

Plouin et al., 1987). They are also frequent in drowsiness, and no obvious stimulus precipitates them. After a series of spasms, the infant may be exhausted and lethargic. Conversely, a brief period of increased alertness that appears to correlate with a brief period of improved background activity in the EEG may also be observed (

Lombroso, 1983;

Gastaut et al., 1964).

ISs may be infrequent at the onset of the disorder. Brief series or even single jerks are then common, and the spasms often go unnoticed; the disease then apparently presents as an isolated developmental deterioration in previously normal infants. The attacks eventually develop into typical clusters. After a period of months or, occasionally, of years, they tend to become less conspicuous. Spontaneously or as an effect of treatment, the spasms may also change their characteristics, becoming more subtle and difficult to detect. Video-EEG monitoring may be necessary to provide firm evidence demonstrating that the spasms have really disappeared in response to medication (

Gaily et al., 2001). The total duration of the spasms is highly variable, depending, in part, on therapy. In rare cases, the spasms are present for only a few weeks, and they then disappear spontaneously (

Dulac et al., 1986a;

Aicardi and Chevrie, 1978). They disappear before 1 or 2 years of age in most patients.

Cowan and Hudson (1991) indicate that spasms have disappeared by 3 years of age in 50% of patients and by 5 years in 90%. In a few patients, repetitive spasms can persist up to 10 to 15 years of age. The age at disappearance is difficult to determine when the spasms become longer and lose their repetitive character, resembling the tonic seizures of Lennox-Gastaut syndrome (

Gastaut et al., 1964).

Other types of seizures commonly precede or accompany the spasms in the course of the disorder and sometimes during a series of spasms (

Carrazana et al., 1993). Preceding seizures are often partial ones. They may occur as part of an acute episode that may be a cause of the syndrome or as isolated seizures (

Velez et al., 1990). Concurrent seizures include focal motor atonic or tonic attacks; isolated myoclonic jerks; and, rarely, atypical absences (

Yamamoto et al., 1988;

Leestma et al., 1984;

Gastaut et al., 1964).

Developmental Retardation or Deterioration

Developmental retardation may exist before the onset of the spasms. In different studies, this was the case

in 68% to 85% of the patients (

Riikonen, 1984;

Kellaway et al., 1983;

Matsumoto et al., 1981a;

Kellaway, 1959). Associated neurologic abnormalities are often present (

Aicardi and Chevrie, 1978). However, identifying mild degrees of cognitive delay retrospectively is difficult, and, even in patients who apparently developed normally before the onset of spasms, mild neurologic antecedents or subtle motor deficits have been found in up to 20% of cases (

Lombroso, 1983a). In previously well infants, a definite behavioral regression is often observed. Social smile disappears; the infant becomes apathetic and hypotonic and no longer takes an interest in its surroundings to the point that blindness is at times suspected (

Aicardi and Chevrie, 1978;

Gastaut et al., 1964). A prospective study in children with perinatal brain injury (

Guzzetta et al., 2002) showed that most of those who subsequently developed West syndrome lost previously acquired visual and cognitive abilities. In some cases, the deterioration of the child’s visual attention abilities paralleled cognitive deterioration, even months before the onset of spasms. Defective visual attention was still present after the acute phase of the syndrome at the age of 2 years. Autistic withdrawal of variable intensity is common at the onset of West syndrome, and it may persist as a long-term sequela in a high proportion of children (

Chugani and Conti, 1996). Motor regression is usually less profound, but voluntary reaching and grasping often disappear (

O’Donohoe, 1985). These behavioral changes may appear before the spasms, but they usually are seen in association with a hypsarrhythmic EEG, or they may go unnoticed, thus leading to suspicion of a primary deteriorating disorder. Because West syndrome is one of the most common causes of mental deterioration in infants, a careful inquiry for mild seizures and an EEG recording should always be obtained in such patients. Even in children with abnormal development before the onset of ISs, the onset of the seizures is often marked by further obvious regression (

Aicardi, 1989;

Aicardi and Chevrie, 1978;

Gastaut et al., 1964). Conversely, in some children, cognitive development may remain normal, at least for a period of time. In such patients, the mental outlook is probably more favorable (

Jeavons et al., 1973). With the subsidence of the attacks, the child’s development may begin to improve somewhat, but the resumption of mental functioning may lag for several weeks after the cessation of seizures.

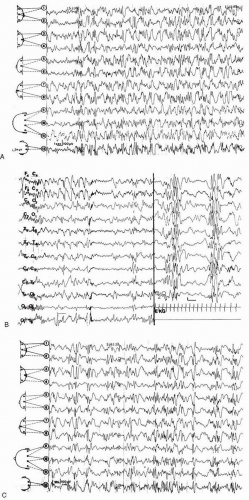

Electroencephalographic Phenomena: Hypsarrhythmia

Hypsarrhythmia (

Gibbs and Gibbs, 1952) is the most remarkable, but not the sole, EEG pattern associated with ISs, as it is observed in 40% to 70% of patients (

Jeavons and Livet, 1992;

Cowan and Hudson, 1991) and it is most common early in the course of the condition. The term refers only to the EEG aspect and it should not be used for designating West syndrome, in which the hypsarrhythmic pattern may not be seen. The pattern is one of very-high-voltage (up to 500 µV) slow waves that are irregularly interspersed with spikes and sharp waves occurring randomly in all cortical areas. The spikes vary from moment to moment in duration and location. They are not synchronous over both hemispheres, so the general appearance is that of a total chaotic disorganization of cortical electrogenesis (

Fig. 3.1). However, the slow components may demonstrate some degree of organization, with rhythms that vary with age (

Parmeggiani et al., 1990). Hypsarrhythmia is an interictal pattern observed mainly in the awake state. During slow sleep, the EEG recording often displays bursts of more synchronous, irregular polyspikes and waves that are separated by stretches of low-amplitude, poorly organized tracing. This pseudo-periodic pattern may be apparent as soon as the child is asleep, or it may take some time to set in (

Kellaway et al., 1983;

Lombroso, 1983a;

Hoeffer et al., 1963). In addition, it may be seen in patients who do not exhibit a typical hypsarrhythmic pattern while they are awake or in those in whom full-blown hypsarrhythmia has not yet appeared. In such patients, it is of definite diagnostic value (

Lombroso, 1983a). During REM sleep, the EEG tracings tend to be closer to normal (

Kellaway et al., 1983;

Lombroso, 1983a;

Gastaut et al., 1964). Typical hypsarrhythmia is present mainly during the early stages of the disorder. It may precede the clinical phenomena by a few weeks. Conversely, in patients with previous EEG abnormalities, the hypsarrhythmic pattern may appear late or not at all.

As the disorder proceeds, the EEG pattern generally changes over weeks or months. Synchrony between the hemispheres and spike-wave complexes of long duration often appear in the late stages, a pattern that has been termed

modified hypsarrhythmia by some investigators (

Hrachovy et al., 1984;

Druckman and Chao, 1955).

The same term is used by other authors to denote the paroxysmal patterns that cannot be called

hypsarrhythmia because of such atypical features as the background activity, partially preserved synchronous bursts of generalized spike-wave discharges, significant asymmetry, or a suppression-burst type of tracing (

Aicardi and Ohtahara, 2002;

Hrachovy et al., 1984;

Lombroso, 1983a;

Jeavons and Bower, 1974). These variants, which may be particularly common in younger children (

Hrachovy et al., 1984) or in those with brain malformations, may be observed in up to 40% of patients with ISs (

Dalla Bernardina and Watanabe, 1994;

Jeavons and Livet, 1992;

Lacy and Penry, 1976).

At least part of the cognitive and/or behavioral deterioration may result from the persistent diffuse hypsarrhythmic EEG activity that can be regarded as a variant of nonconvulsive status (

Dulac, 2001); if this is so, maximal efforts at control are clearly in order (see

“Treatment and Course”).

The hypsarrhythmia tends to disappear in older patients, occasionally even when spasms may still be observed (

Hrachovy and Frost, 1989;

Jeavons et al., 1973). A typical hypsarrhythmic EEG is rare after the age of 3 years. The tracings may then become normal, or they may exhibit various abnormalities, especially focal spikes or slowing. The replacement of a hypsarrhythmic pattern with bilateral, symmetric slow spike-waves is common when Lennox-Gastaut syndrome develops following ISs (

Watanabe et al., 1973;

Gastaut et al., 1964).

The association of hypsarrhythmia with a constant focus of abnormal discharge is common (

Riikonen, 1982;

Gastaut et al., 1964), and, when focal discharges have a fixed topography, they often indicate focal pathology, especially when slow waves are prominent (

Parmeggiani et al., 1990). Some investigators advise systematic use of intravenous diazepam to suppress the diffuse hypsarrhythmia, thus unmasking potential focal discharges (

Dalla Bernardina and Watanabe, 1994;

Dulac et al., 1986a). Asymmetric hypsarrhythmia is less common, while unilateral hypsarrhythmia is rare.

The hypsarrhythmic pattern may fail to appear for brief periods at onset of the disorder or after treatment, or it may always remain atypical. It does not appear with certain etiologies, such as lissencephaly or the Aicardi syndrome (see

“Malformation of the Cerebral Cortex”). However, a consistently normal tracing, including sleep recording, virtually rules out the diagnosis of ISs (

Lombroso, 1982,

1983a).

The ictal EEG patterns are variable (

Dulac et al., 1986a;

Kellaway et al., 1979;

Gastaut et al., 1964). The most common is a high-voltage, frontal-dominant, generalized slow-wave transient pattern with an inverse phase reversal over the vertex region (

Fusco and Vigevano, 1993), followed by voltage attenuation. Bilateral and diffuse fast rhythms in the β-range (and occasionally in α-band) coincide with the clinical spasm and with the initial part of the low-voltage record, which lasts 2 to 5 seconds. In many patients, only voltage attenuation (decremental discharge) is present. Such electrical events may occur without apparent clinical concomitants (

Hrachovy et al., 1984;

Gastaut et al., 1964). Spasms with a more sustained tonic contraction are accompanied by the typical high-amplitude slow wave, followed by fast activity that is similar to that accompanying tonic seizures (

Vigevano et al., 2001).

Other ictal patterns include generalized sharpwave and slow-wave complexes, generalized slow-wave transients only, or fast rhythms occurring in isolation (

Kellaway et al., 1979,

1983). Asymmetric and unilateral spasms are usually associated with contralateral EEG activity, suggesting a cortical generator for the spasms (

Gaily et al., 1995;

Donat and Wright, 1991a) and unilateral damage. Several ictal patterns may be combined, or they may vary from episode to episode. During a cluster, focal discharges may occur (

Donat and Wright, 1991b). After the initial spasms of a series, transient suppression of the hypsarrhythmic pattern may be seen (

Lombroso, 1983a;

Gastaut et al., 1964) without a return of hypsarrhythmic activity between consecutive spasms. In other cases, hypsarrhythmia resumes between spasms. According to

Dulac (1997), disappearance of hypsarrhythmia in the course of a series of spasms might indicate a symptomatic origin, whereas the resumption of hypsarrhythmia between serial spasms may indicate an “idiopathic” condition and may have a favorable prognosis. However, this finding has been disputed.

Children with organic lesional or severe encephalopathies, such as tuberous sclerosis, Aicardi syndrome, or lissencephaly, do not usually have typical hypsarrhythmia. Likely, only children with less severe brain impairment and better chances of less severe outcome are able to generate such an electrographic pattern.