18 Infection

I. Key Points

– Swift and accurate diagnosis of spinal infections is necessary to prevent structural instability or neurologic compromise.

– Hematogenous spinal infections develop from the seeding of the cartilaginous end plates, which allows pathogens to propagate within the avascular disc space before spreading to the adjacent vertebral bodies.

– Granulomatous infections may be caused by one of several fungal, bacterial, and spirochete pathogens that generally give rise to an indolent clinical course.

– Postoperative infections most often develop secondary to direct inoculation of the wound with skin flora and are characterized by pain and tenderness at the surgical site.

II. Pyogenic Vertebral Osteomyelitis and Discitis1–4

– Background

• Vertebral osteomyelitis accounts for about 1% of all skeletal infections.

• Discitis typically arises as a result of hematogenous spread such that the pathogens emanate from the vascular end plates into the avascular disc space before disseminating to the adjacent vertebral bodies.

• Pyogenic infections most frequently involve the lumbar spine (58%), followed by the thoracic (30%) and cervical (11%) regions.

• Gram-positive organisms such as Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus species are the most commonly isolated organisms (67 and 24% of cases, respectively).

– Signs, symptoms, and physical examination

• The most prevalent signs and symptoms are axial pain (86%) and fever (60%).

• Neurologic changes such as radicular numbness and muscle weakness may be present in as many as one-third of patients.

• Patients should be questioned regarding any ongoing constitutional symptoms, travel history, or recent procedures that may be suggestive of a diagnosis of infection.

– Workup

• White blood cell count (WBC) may be increased in these patients, although in many this value will be normal.

• Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) is more sensitive but is relatively nonspecific for infection.

• C-reactive protein (CRP) is elevated in at least 90% of patients with spinal infections and is a reliable indicator of the disease course because it tends to rise acutely with the onset of an infection but returns to baseline rapidly as it resolves.

• Blood cultures may be useful because they have been shown to reveal the causative pathogen in up to 58% of hematogenous spinal infections.

• Urinalysis and culture with sensitivities should also be obtained to rule out an infection of the urinary tract, which may spread to the spine.

– Neuroimaging

• Plain radiographs are the standard form of initial imaging study for suspected cases of spinal infections and will frequently exhibit abnormalities (89% of cases).

• Computed tomography (CT) may display early pathologic changes within the spinal column as well as any fluid collections in the surrounding soft tissues.

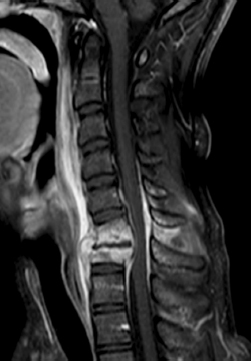

• Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the ideal diagnostic modality for identifying pyogenic discitis.

Edema and fluid may be evident within the discs and adjacent tissues on T2-weighted images.

Edema and fluid may be evident within the discs and adjacent tissues on T2-weighted images.

Addition of gadolinium contrast can enhance the visualization of paraspinal and epidural enhancement suggestive of active infection.

Addition of gadolinium contrast can enhance the visualization of paraspinal and epidural enhancement suggestive of active infection.

• Technetium-99m/gallium-76 citrate bone scans or indium-111 tagged WBC studies are extremely sensitive for diagnosing spinal infection but are less specific.

– Treatment

• First-line treatment for pyogenic infections is administration of broad-spectrum intravenous (IV) antibiotics for at least 6 to 8 weeks until culture-specific regimens may be initiated.

Identify the pathogen with biopsy, blood, or tissue cultures prior to treatment initiation.

Identify the pathogen with biopsy, blood, or tissue cultures prior to treatment initiation.

• Immobilization may be beneficial for reducing pain and stabilizing the spine.

• Surgery may be warranted if appropriate medical management fails or if the patient develops neurologic deterioration or spinal instability/deformity.

• The goals of surgery include debridement of the infected tissue, decompression of the neural structures, and stabilization of the spine.

– Surgical pearls

• Vertebral osteomyelitis and discitis frequently affect the spinal column and may require an anterior procedure (Fig. 18.1).

• Posterior stabilization may also be necessary in instances where there is significant instability or deformity.

Avoid stainless steel implants in these cases as there is a tendency for bacteria to form a biofilm on them.

Avoid stainless steel implants in these cases as there is a tendency for bacteria to form a biofilm on them.

Titanium implants are preferred because they don’t promote bacterial biofilm colonization.

Titanium implants are preferred because they don’t promote bacterial biofilm colonization.

• Autogenous bone is an excellent graft material for fusion in an infected surgical field, although allograft and metal may also be reasonable options for select cases.

Fig. 18.1 Cervical discitis/epidural abscess with end plate involvement, relative sparing of the vertebral body, and epidural collection compromising the cervical canal.

III. Granulomatous Infections1,2,4,5

– Background

• Granulomatous infections caused by certain bacteria, fungi, and spirochetes are far less common than pyogenic infections in the United States (US).

• Spinal inoculation generally is done within the peridiscal metaphysis of the vertebral body adjacent to the end plate.

An inflammatory response produces a granuloma with a caseous abscess.

An inflammatory response produces a granuloma with a caseous abscess.

The infection propagates along the anterior longitudinal ligament to encompass contiguous levels.

The infection propagates along the anterior longitudinal ligament to encompass contiguous levels.

• The most common pathogen is Mycobacterium tuberculosis, an atypical bacteria that is more prevalent in underdeveloped nations but is becoming more common in the US.

Pott described the first surgical drainage of a tuberculous abscess in 1779, and his name has become synonymous with spinal disease.

Pott described the first surgical drainage of a tuberculous abscess in 1779, and his name has become synonymous with spinal disease.

Neurologic deficits may be observed in up to 47% of affected individuals.

Neurologic deficits may be observed in up to 47% of affected individuals.

The spine is the most common site of skeletal involvement (1% of all patients and nearly 50% of those with musculoskeletal manifestations).

The spine is the most common site of skeletal involvement (1% of all patients and nearly 50% of those with musculoskeletal manifestations).

• Fungal species (e.g., Aspergillus, Blastomyces, Coccidioides, Cryptococcus, and Histoplasma), spirochetes (e.g., Actinomyces israelii and Treponema pallidum), and parasites are more unusual causes of granulomatous spinal infections.

– Signs, symptoms, and physical examination

• Granulomatous spinal infections are characterized by a prolonged duration (i.e., months to years) of symptoms, including back pain and constitutional complaints.

• The thoracic spine is the most common region of the spine for infection, which may give rise to significant kyphotic deformities.

• Neurologic compromise and paraplegia may develop more frequently with tuberculous infections than with pyogenic osteomyelitis due to their predilection for the posterior elements.

– Workup

• All patients should be assessed with a tuberculin purified protein derivative (PPD) skin test.

• ESR, CRP, WBC, and blood cultures may be less informative in these cases.

• Sputum should be acquired for acid-fast bacilli (AFB) and fungal cultures.

– Neuroimaging

• Individuals suspected of having tuberculous infections should be assessed with a chest x-ray, which may demonstrate pulmonary disease as well as any extensive bony lesions or focal kyphosis.

• MRI is the imaging modality of choice and will often show destruction of the vertebral bodies with relative sparing of the intervertebral discs.

– Treatment

• Pathogen-directed antimicrobial therapy

Six to 12 months of a multidrug treatment, including isoniazid, rifampin, pyrazinamide, and streptomycin or ethambutol is the standard regimen for Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

Six to 12 months of a multidrug treatment, including isoniazid, rifampin, pyrazinamide, and streptomycin or ethambutol is the standard regimen for Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

Antifungals such as amphotericin B or ketoconazole are employed for culture-documented fungal disease.

Antifungals such as amphotericin B or ketoconazole are employed for culture-documented fungal disease.

Surgical intervention is not routinely performed for these infections unless there is a failure of pharmacotherapy, progression of deformity, instability, or neurologic decline.

Surgical intervention is not routinely performed for these infections unless there is a failure of pharmacotherapy, progression of deformity, instability, or neurologic decline.

– Surgical pearls

• These types of infections may bring about considerable destruction of the vertebral bodies, which may require reconstruction of the anterior column.

• Supplementary posterior fixation may also be indicated to minimize the risk of developing a postoperative deformity.

• Colonization of metallic implants rarely occurs with granulomatous infections.

Avoid stainless steel implants

Avoid stainless steel implants

Postoperative imaging with CT and MRI is easier with titanium implants (decreased artifact compared with stainless steel implants).

Postoperative imaging with CT and MRI is easier with titanium implants (decreased artifact compared with stainless steel implants).

IV. Epidural Infections

– Background

• Abscesses most often arise from adjacent vertebral osteomyelitis/discitis but may also develop from hematogenous extension or direct inoculation from spinal procedures.

• Staphylococcus aureus is the most common pathologic organism.

• Epidural infections usually affect the thoracic and lumbar spines, where they typically exist in the posterior epidural space; in the cervical spine they are normally located anterior to the thecal sac.

– Signs, symptoms, and physical examination

• Patients regularly complain of axial pain but symptoms may be more subtle with less virulent organisms.

• Larger lesions may compress the neural elements and give rise to neurologic deficits.

– Workup

• Standard infection laboratories (e.g., WBC, ESR, and CRP) with blood cultures

• Identification of a specific pathogen may require a needle or open biopsy to acquire tissue for culture.

– Neuroimaging

• MRI is the most sensitive and specific imaging study because it clearly demonstrates any fluid collection in the epidural space.

– Treatment

• Patients who are neurologically intact may be candidates for nonsurgical treatment consisting of long-term antibiotic therapy.

• Surgical decompression ± stabilization is generally indicated for individuals who have failed medical management or who present with neurologic deterioration.

– Surgical pearls

• Operative approach is largely influenced by the location of the infection.

• While a laminectomy may be sufficient to address posterior abscesses, an anterior procedure may also need to be performed in the setting of vertebral osteomyelitis or ventral abscess.

• Concomitant arthrodesis may be warranted in cases where spinal instability has been caused by the infection or any subsequent decompression.

V. Postoperative Infections1,2,4,6

– Background

• Surgical site infection (SSI) has been reported in up to 12% of adults undergoing spinal operations.

• SSI is associated with longer hospital stays, higher complication rates, and increased mortality.

• Risk factors for SSI include increased age, obesity, diabetes, tobacco use, poor nutritional status, greater intraoperative blood loss, prolonged surgical time, complete neurologic injuries, revision surgery, placement of instrumentation, disseminated cancer, and a posterior operative approach.

• Postoperative SSI ordinarily arises following direct inoculation of the wound with normal skin flora.

– Signs, symptoms, and physical examination

• The typical SSI is clinically evident and associated with obvious erythema, edema, and drainage from the incision, although subfascial lesions may yield few external signs of infection.

• Patients may or may not complain of pain or exhibit constitutional symptoms.

– Workup

• WBC, ESR, and CRP are frequently elevated and may be used as serial markers to confirm the resolution of a SSI.

• Wound cultures are essential for directing antimicrobial therapy.

Sampling of deep wound collections is preferable since superficial drainage is prone to contamination with skin flora.

Sampling of deep wound collections is preferable since superficial drainage is prone to contamination with skin flora.

Intraoperative cultures represent the ideal method for identifying the causative organism.

Intraoperative cultures represent the ideal method for identifying the causative organism.

– Neuroimaging

• CT may reveal pathologic changes such as an abscess or hematoma, but these findings may be difficult to differentiate from nonspecific postoperative changes.

• MRI is ideal for identifying fluid collections, but in many cases there will be an increased signal on T2-weighted images and contrast enhancement in the surgical field regardless of whether a SSI is present.

– Treatment

• Prophylactic antibiotics administered 60 minutes before a spinal procedure have been shown to reduce the incidence of SSI by up to 60%.

• Additional doses of intraoperative antiobiotics should be dispensed for prolonged surgical procedures with significant blood loss or gross contamination.

• Definitive therapy for established SSI is open irrigation and debridement.

• IV antibiotics are typically continued for a minimum of 6 weeks, at which time patients may be switched over to oral medications depending on clinical course and laboratory profile.

– Surgical pearls

• Deep wound cultures should be obtained intraoperatively prior to the delivery of antibiotics and irrigation of the tissues.

• Metallic hardware is frequently left in place to maintain stability, but any loose bone graft should be removed to prevent the formation of a nidus of bacteria.

• Following open irrigation and debridement, the wound may be closed primarily over drains, covered with a vacuum dressing, or left open.

Common Clinical Questions

1. Which laboratory test is best for following the resolution of a spinal infection?

A. White blood cell count

B. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate

C. C-reactive protein

D. Platelet count

2. What are the most common organisms that are isolated in cases of vertebral osteomyelitis and discitis?

A. Gram-positive cocci

B. Gram-negative rods

C. Mycobacterium tuberculosis

D. Fungi

3. Surgical intervention is most clearly indicated for which of these conditions?

A. L3-L4 discitis associated with low back pain

B. Incisional drainage following a recent discectomy

C. Granulomatous infection involving the T6-T7 vertebral bodies with no obvious deformity or compression of the neural elements

D. C5-C6 epidural fluid collection resulting in progressive weakness and numbness

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree