Chapter 76 Insomnia

Epidemiology and Risk Factors

Abstract

Twenty-six percent of people complain of difficulty falling asleep and 42% complain of difficulty staying asleep at least a few nights a week.1 These survey results illuminate the potential grandiose magnitude of insomnia, but they also serve to caution us that a sleep complaint alone does not in itself rise to the standard of clinical insomnia. Indeed, if treatment-seeking behavior is a proxy for clinical significance, a more-constrained picture emerges. Only 13% of persons complaining of insomnia seek professional treatment, though this rate increases with insomnia severity and advancing age.2

Epidemiology

Definition of Insomnia

Given this complexity, it is not surprising that the literature contains numerous definitions of insomnia, ranging from the broad and inclusive to the narrow and exclusive. For example, some epidemiologic studies have relied on respondents to provide their own definitions by simply asking whether or not they have trouble sleeping,3 whereas other studies have defined insomnia more narrowly using quantitative severity threshold criteria, such as greater than 30 minutes of sleep-onset latency or wake time after sleep onset.4 Unfortunately, the study of insomnia has been hampered by such varied definitions of insomnia as evidenced by a review of epidemiologic studies in which prevalence rates in the general population ranged from 4% to 48% depending on the definition used.5 Efforts to standardize insomnia criteria6 might prove helpful in the future.

A consensus has begun to emerge in the literature that the core symptoms of insomnia include at least one sleep symptom and one wake symptom. The sleep symptom(s) include a report of difficulty initiating or maintaining sleep, early morning awakening, or nonrestorative or nonrefreshing sleep. The wake symptom(s) include a report of sleep-associated daytime impairment, such as sleepiness, fatigue, mood disturbance, cognitive difficulties, social impairment, or occupational impairment.7 Research supports the clinical utility of considering associated daytime impairment, because persons with both sleep and wake symptoms are more likely to seek treatment than those who report sleep symptoms alone.8

In a formal attempt to improve standardization, sensitivity-specificity analyses were performed on data from 61 clinical trials conducted during the 1980s and 1990s. The aim of these analyses was to determine common practices for defining quantitative criteria for the diagnosis of chronic insomnia: frequency (insomnia symptoms occur at least 3 nights a week), severity (sleep-onset latency or wake time after sleep onset of at least 31 minutes per night), and duration (insomnia symptoms have been present for at least 6 months).9 The American Academy of Sleep Medicine took another notable, formal attempt at standardization in 1999 by appointing a work group to develop research diagnostic criteria (RDC) for insomnia.10 In 2004, this work group published their recommendations, which included a universal definition for chronic insomnia (plus RDC for nine specific diagnostic types and normal control samples; Box 76-1).

Box 76-1

Adapted from Edinger JD, Bonnet MH, Bootzin RR, et al. Derivation of research diagnostic criteria for insomnia: report of an American Academy of Sleep Medicine Work Group. Sleep 2004;27:1567-1596.

Research Diagnostic Criteria

Universal Definition for Insomnia Disorder

Evaluation

Epidemiological data have traditionally relied on self-report data because large-scale data collection using objective methods (polysomnography [PSG] or actigraphy) is expensive and cumbersome. Further, self-report instruments better capture sleep perception than objective methods, and the subjective view may have greater import for insomnia than objective assessment.6

Self-reported accounts of one’s sleep experiences are necessarily retrospective in nature. However, the time period over which published studies have asked subjects to provide sleep estimates has varied widely—from 1 year to the previous night.4 Because asking respondents to provide single-point estimates of their sleep over extended time periods (days, months, years) poses specific methodologic limitations that are less of a concern when data is estimated for the previous night, the term prospective takes on a different connotation when referring to the epidemiology literature. Specifically, prospective typically refers to a future event, but in this context, it is used to refer to sleep diary data that collects information on sleep from the night just completed. This distinction is important, because sleep diaries allow researchers to capitalize on the immediacy of retrospective data.

A review of the typical methodology used by 42 studies conducted during the mid 1970s through 2002 revealed that the overwhelming majority (n = 40) relied on retrospective assessment using either an interview or self-administered survey to collect data at a single point in time.4 At that time, only two studies had used a prospective assessment approach, collecting daily sleep diaries for 1 week.11,12 Subsequently, an epidemiologic study was reported that used 2 weeks of daily sleep diaries.4

The heavy reliance on retrospective assessment is problematic because of the increased risk of recall errors and unreliability when respondents are asked to provide sleep estimates over long periods of time. The recall bias introduced by retrospective estimates may produce overestimates of insomnia symptoms. Retrospective estimates of total sleep time and number of awakenings are poorly correlated with similar sleep diary estimates,13 and PSG sleep variables correlate better with daily sleep diaries than with retrospective reports.14 Additionally, retrospective estimates can introduce unreliability, because single point estimates may be susceptible to situational influences that are temporary. Momentary emotional states (e.g., work-related stress, depressed mood) tend to influence recall more than do routine experiences. Recency bias can also introduce unreliability because participants can exhibit a tendency to respond based on their previous night’s sleep. Another problem plaguing some retrospective studies is the absence of a specified time period of assessment. For example, some studies asked respondents to report how they “usually” or “generally” sleep.

Prospective assessment using at least 1 week of sleep diaries, preferably 2, avoids or reduces many of the limitations inherent in retrospective assessment.15 It also allows a richer characterization of sleep, because sleep diaries provide detailed quantitative descriptions (i.e., sleep-onset latency, wake time after sleep onset, number of awakenings, total sleep time, sleep efficiency) and information on type of insomnia (i.e., onset, maintenance, terminal).

Prevalence

Nowhere is the impact of inconsistent definitions and assessment more evident than in the wide range of insomnia prevalence estimates (4% to 48%) available for the general population.5 In a review5 of more than 50 epidemiologic studies of insomnia based on samples or populations from around the world, this review provides prevalence rates for each of four main definitional categories and three subcategories. As illustrated in Table 76-1, prevalence rates drop precipitously as the stringency of criteria increase. Applying the most lenient criteria—presence of insomnia symptoms without any frequency or severity qualifiers—prevalence rates of up to 48% were found, whereas the most restrictive criteria—insomnia diagnosis based on DSM-IV-TR criteria7—revealed more modest prevalence rates of about 6%. Notably, prevalence rates also stabilized as criteria tightened so that the rates reported for the studies using DSM-IV-TR criteria demonstrated a narrow 2-point range (4.4% to 6.4%), whereas those examining insomnia symptoms demonstrated the greatest variability, with a broad 38-point range (10% to 48%).

Table 76-1 Prevalence Rates by Four Main Definitional Categories and Three Subcategories

| DEFINITION | PREVALENCE (%) |

|---|---|

| Definitional Categories | |

| DSM-IV insomnia diagnosis (n = 5) | 4-6 |

| Dissatisfaction with sleep quantity or quality (n = 11) | 8-18 |

| Insomnia symptoms plus daytime consequences (n = 8) | 9-15 |

| Insomnia symptoms* (n = 21) | 10-48 |

| Insomnia Symptoms (Subcategories) | |

| Insomnia symptoms only | 30-48 |

| Insomnia symptoms plus frequency criteria (≥3 nights/week or often/always) | 16-21 |

| Insomnia symptoms plus severity criteria (moderately to extremely) | 10-28 |

DSM-IV, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition, text revision.

* Insomnia symptoms included difficulty initiating or maintaining sleep. Some studies also included nonrestorative sleep as a symptom.

Adapted from Ohayon MM. Epidemiology of insomnia: what we know and what we still need to learn. Sleep Med Rev 2002;6:97-111.

The overwhelming majority of studies included in this review used some type of retrospective assessment. This is not surprising given the large degree of overlap between the studies reviewed by Ohayon5 and the Lichstein and colleagues4 review previously discussed. Given the importance of the distinction between retrospective and prospective assessment, it seems prudent to examine the prevalence of insomnia when prospective assessment is used. This discussion focuses on the Lichstein and colleagues study,4 which used a stratified random sampling procedure to recruit at least 50 men and 50 women in each age decade from 20 to 29 years to 80+ years from Memphis, Tennessee, and neighboring suburbs. Although at least two other studies11,12 have used prospective assessment, this study was chosen because it provides the strongest methodological rigor of the prospective studies. Specifically, this study used random-digit dialing sampling, 2 weeks of sleep diaries, quantitative insomnia criteria including daytime impairment, and sampling across a broad age range and among different ethnic groups.

The overall prevalence of insomnia, weighted by gender and age, was 15.9%. This rate is higher than expected based on Ohayon’s documentation of the decrease in rate with increased methodological rigor. The reason underlying the difference in rates between the 4% to 6% rates found in studies using DSM-IV-TR criteria and the approximately 16% rate found in this study using empirically based quantitative criteria and prospective assessment is unclear. This study also provides novel information on the prevalence of four unique insomnia types (Table 76-2).

Table 76-2 Prevalence of Insomnia by Insomnia Type

| TYPE | DEFINITION | PREVALENCE (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Onset | Satisfies quantitative criteria for onset insomnia only (SOL ≥31 min, ≥3 nights a week) | 22.8 |

| Maintenance | Satisfies quantitative criteria for maintenance insomnia only (WASO ≥31 min, ≥3 nights a week) | 31.6 |

| Mixed | Does not separately satisfy quantitative criteria for onset or maintenance insomnia, but has at least 3 insomnia nights a week (1 or 2 nights of SOL ≥31 min, and 1 or 2 nights of WASO ≥31 min) | 16.9 |

| Combined | Separately satisfies quantitative criteria for both onset and maintenance insomnia (SOL ≥31 min, ≥3 nights a week, and WASO ≥31 min, ≥3 nights a week) | 28.7 |

SOL, sleep-onset latency; WASO, wake after sleep onset.

Adapted from Lichstein KL, Durrence HH, Riedel BW, et al. Epidemiology of sleep: age, gender, and ethnicity. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2004.

Comorbidities

Comorbid insomnia is an important topic that has not received much attention in the epidemiology literature. This is because historically, insomnia occurring in the context of another disorder (medical or psychiatric) has been viewed as a symptom of that disorder and labeled secondary insomnia. Unfortunately, it is difficult to determine whether insomnia is a symptom secondary to another disorder or a separate disorder (comorbid), because insomnia that initially occurs secondary to some other condition often becomes an independent problem or a partially independent problem that shares a reciprocal relationship with the original primary disorder. In recognition of the difficulty inherent in drawing conclusions about causality, a 2005 NIH State-of-the Science Consensus panel16 recommended that the term comorbid insomnia replace the term secondary insomnia. Greater focus on comorbid insomnia in the epidemiology literature is warranted because of its common occurrence, potentially accounting for up to 90% of insomnia in the general population.17,18,19

The most common comorbidities associated with insomnia are psychiatric disorders, including anxiety, depression, panic disorder, adjustment disorder, somatoform disorders, and personality disorders. Comorbidity rates between insomnia and psychiatric distress, particularly anxiety and depression,20,21 have been found to be as high as 77% in clinical cases.20 However, epidemiologic studies examining the association between clinically significant levels of anxiety and depression and insomnia in the general population have revealed lower rates. One study22 examined comorbidity between insomnia and mental disorders in a representative French cohort (n = 5622). Of their total sample, 17.7% fit one of six DSM-IV-TR insomnia categories. Of subjects with a diagnosis of insomnia, only 7.3% qualified for a diagnosis of primary insomnia. However, even in those participants, the prevalence of subclinical depressive or anxiety symptoms was extremely high (90%). The distribution of the remaining 92.7% of participants with insomnia into the four other diagnostic categories was as follows:

Another study23 found similar rates for depression and anxiety. Specifically, they found 20% percent of people with insomnia displayed clinically significant depression and 19.3% demonstrated clinically significant anxiety. People with insomnia were 10 times more likely to have depression and 17 times more likely to have anxiety than normal sleepers.

Medical conditions that commonly co-occur with insomnia include arthritis, cancer, hypertension, chronic pain, coronary heart disease, and diabetes. Several studies have examined the association of insomnia and medical conditions in older persons. For example, in a cross-sectional study of 9000 persons 55 to 84 years of age, Foley and colleagues24 found an association between history of insomnia and difficulties with activities of daily living, respiratory symptoms, and other health problems, including hypertension, heart disease, cancer, stroke, diabetes, and hip and other fractures. A 3-year follow-up (N = 6800) revealed that heart disease, stroke, hip fracture, and respiratory symptoms were associated with incident insomnia. Heart disease, diabetes, respiratory symptoms, and stroke were also associated with the maintenance of insomnia.25 The 2003 National Sleep Foundation’s Sleep in America Survey found that 69% of respondents with one or more sleep problems also had four or more medical conditions.26 Only 36% of those with no major medical conditions reported sleep problems.

Several other studies have examined adults across the lifespan. In a survey of 3161 adults19 18 to 79 years of age, those who reported insomnia symptoms (difficulty falling asleep, difficulty staying asleep, or waking too early) were more likely to report having two or more health problems than were normal sleepers. A study of 12,643 Hungarians27 found that people with insomnia exhibited greater use of health care, in terms of sick leave, emergency department visits, and hospitalization, than normal sleepers.

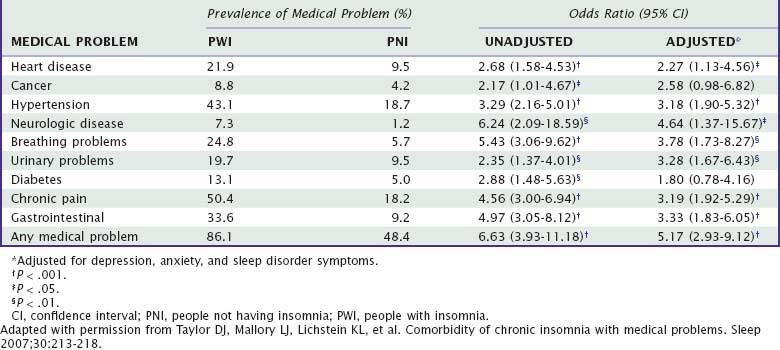

Another study28 focused on prevalence rates of medical problems in persons with insomnia in the general population. Controlling for anxiety, depression, and symptoms of other sleep disorders, they found persons with insomnia had a higher prevalence of comorbid medical problems than did persons without insomnia (Table 76-3). Additionally, persons with chronic medical problems had a higher prevalence of insomnia than did people without those problems (Table 76-4).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree