Module 1

Psycho-education on CBT and OCD

The treatment rationale is presented and includes a description of OCD symptoms (obsessions and compulsions), prevalence, and main principles of conducting online CBT treatment. Different fictional patient characters are introduced (each example represents a specific OCD symptom dimension). The participant has the opportunity to follow one or all four characters (washing, checking, symmetry, or violent thoughts).

Homework: Register OCD symptoms in the Internet platform diary.

Module 2

Assessing OCD symptoms with the CBT model

The autonomic nervous system and its interaction with OCD symptoms is explained. Participants begin to link obsessions and compulsions to the OCD cycle and learn how to conduct a functional analysis of their OCD problems. Each OCD cycle is presented visually for each example character.

Homework: Continue OCD diary registrations and apply these to the OCD cycle.

Module 3

Cognitive restructuring

Common OCD meta-cognitions are explained, such as inflated responsibility, absolute need for certainty, thought-action fusion and exaggerated need to control thoughts. The focus is to register and discuss meta-cognitions with the psychologist from a functional perspective.

Homework: Continue OCD diary registrations and use these registrations to analyze meta-cognitions associated with obsessions.

Module 4

Establish treatment goals and exposure hierarchy

Introduction to exposure with response prevention (ERP). Different strategies for conducting ERP are explained and examples given of treatment goals and different ways of constructing exposure hierarchies for each example character.

Homework: Register treatment goals and then construct an exposure hierarchy with the information from these goals.

Module 5

Exposure with response prevention (ERP)

Different aspects of ERP are highlighted, along with common obstacles associated with ERP and how to overcome them. The participant then chooses an ERP exercise at the bottom of the exposure hierarchy.

Homework: Start ERP and report to the psychologist after 2 days.

Modules 6–9

ERP exercises

Each module focuses on certain ERP exercises with examples from each treatment character. The text for each module is short (1–2 pages), as the focus is reporting and planning the weekly exposures.

Homework: Conduct daily ERP and report to the psychologist at least once per week.

Module 10

ERP exercises. Establishing valued directions for further improvements

The modules focus on daily ERP with further exercises added that are adopted from acceptance and commitment therapy. These include establishing valued based goals and how they are applied in daily exposure tasks. The treatment is summarized, and the participant learns the distinction between relapse and setback and further treatment strategies. The participant establishes a relapse prevention program based on his/her valued based goals.

Homework: Continue ERP. Establish valued based goals and apply them in daily exposure exercises. Summarize the treatment and establish a relapse prevention plan.

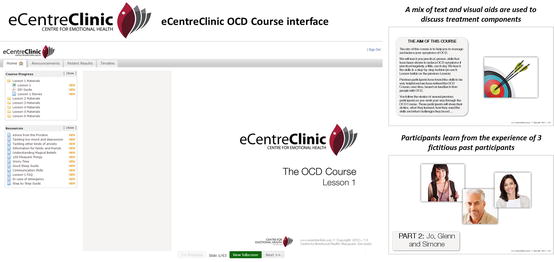

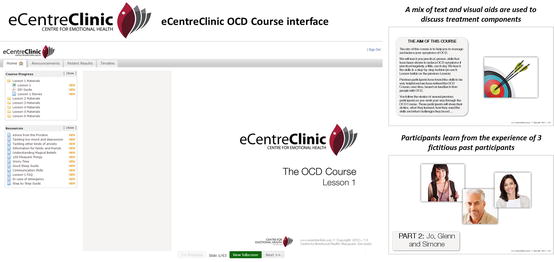

eCentreClinic, Australia

The eCentreClinic is a research clinic located at Macquarie University that aims to develop and evaluate ICBT programs for a variety of mental health conditions. The eCentreClinic OCD Course uses both cognitive and behavioral treatment techniques (including ERP) that are based on best-practice face-to-face treatment for OCD. The treatment techniques are described from the perspective of both a clinician and fictional characters. The course is hosted on a secure website and the lessons are released according to a set timetable to ensure that participants adhere to the structure of the program and participants are not able to read ahead. Automated emails are programmed into the system and are sent to participants (1) when a lesson becomes available, (2) to remind the participant to complete a lesson, and (3) when the participant completes a lesson. When a participant completes a lesson, they then download an overview of the lesson and this overview includes their homework tasks; however, homework tasks are not submitted to the therapist for review. Participants generally obtain brief (i.e., 5–10 min) but regular (i.e., twice per week) therapist support via the telephone; however, self-guided interventions have also been studied. Due to the high comorbidity rates of mood and other anxiety disorders, the eCentreClinic OCD Course also makes available additional self-help materials to address these comorbidities. An overview of the eCentreClinic OCD Course interface and examples of treatment information can be seen in Fig. 6.1

.

Fig. 6.1

Overview of the eCentreClinic OCD Course Content

“Internet-Based Therapist-Guided Writing Therapy,” Germany

This treatment was developed by Herbst and colleagues and is referred to as “Internet-based therapist-guided writing therapy” (Herbst et al. 2014). In this treatment, the patient and the therapist have two sessions per week, where they communicate synchronously in a treatment platform through text alone. There is no standardized self-help text, as in the Swedish and Australian ICBT protocols, and the treatment is, as in face-to-face CBT, provided by the therapist. Content wise, this treatment is similar as the other ICBT and face-to-face protocols as the main intervention is ERP.

“OCFighter™,” USA

OCFighter is an Internet adaptation of the BTSteps program, which is a 9-step computerized treatment that utilizes a touch-tone telephone to deliver information related to the treatment of OCD. OCFighter is hosted on a secure website and consists of a number of interactive videos that are narrated by a therapist. The therapist explains how to use the program and provides psychoeducation on OCD and ERP. The program assists participants to develop their own relevant exposure hierarchy and allows participants to track their progress via interactive logging of exposure tasks and subjective units of distress. The 9 steps are not completed according to any specific timeline; however, participants must generally wait 24 h before commencing the next step in the program. An overview of the OCFighter program and examples of the interface are displayed in Fig. 6.2

. While BTSteps has been demonstrated to be efficacious in several RCTs (Greist et al. 2002; Kenwright et al. 2005), the efficacy of the Internet-administered version (OCFighter) has been demonstrated in only one open trial to date.

Fig. 6.2

Overview of the OCFighter Program Content

Effects in Research and Clinic

The KI Program

Pilot Study

The ICBT treatment at the KI was first tested in an open pilot study where 23 adult OCD patients received 15 weeks of treatment (Andersson et al. 2011). Mean OCD symptom duration was 13 years, most had received previous OCD treatment, and the majority of participants had a high school education or above. The Y-BOCS was administered by a psychiatrist at pre- and posttreatment (there was no data loss), and a large within-group effect size was observed (d = 1.56), with 61 % classified as responders and 41 % classified as being in remission at posttreatment.

Randomized Controlled Trial

The results of the pilot study were later replicated and extended in a randomized controlled trial (RCT) where 101 OCD participants were randomized either to 10 weeks of ICBT or to a control condition, which consisted of online supportive therapy (basic attention control) (Andersson et al. 2012). Most subjects were self-referred and blind assessors conducted the Y-BOCS at posttreatment and at 4-month follow-up. All subjects were started in treatment on the same day and were treated simultaneously. The attrition rate was low (1 %) in this study and results showed a significant interaction effect with a large between-group effect size (d = 1.12) favoring ICBT, and results were sustained at follow-up. The within-group effect size in the ICBT group (pre to post: d = 1.55) was similar to that seen in the pilot study. The therapists in this study were psychology students in their final year of training. We concluded that the treatment was promising, despite the long-standing symptoms, previous treatment failures, and small amount of therapist contact required (approximately 13 min per week per patient).

Long-Term Efficacy and Relapse Prevention by Adding a Booster Program

Although both the pilot study and the RCT showed promising results, the long-term efficacy of ICBT required investigation. This subsequent study aimed to (1) investigate the long-term effects of ICBT and (2) test if an Internet-based booster program could further enhance the treatment effects (Andersson et al. 2014). Half of the sample was randomized to a 3-week Internet-based booster program 6 months after receiving ICBT and follow-up data from the RCT was obtained at 7, 12, and 24 months. Assessors were blind to treatment allocation. The booster treatment in this study followed the same procedure as in the RCT (i.e., written self-help material, consecutive access to materials, integrated therapist contact, etc.), but the treatment content differed significantly. In our previous trial, we regarded the therapist as an external stimulus with the main function to reinforce ERP behaviors. In the booster treatment developed in this study, the main aim was to get the patient to develop external stimuli in his/her natural environment that could reinforce further ERP (i.e., a partner, friend, or family member). Thus, instead of coaching the patient several times per week to do ERP, the therapists in this study instead coached the patient to utilize a support person that he/she could use to facilitate weekly checkups with and plan the upcoming exposure exercises.

Results from this study showed that the effect of ICBT was sustained at follow-up for the completer sample across the different assessment points using the Y-BOCS (d = 1.58–2.09) (Andersson et al. 2014). The booster treatment group had a significant improvement at 7 months but not at 12 or 24 months on the Y-BOCS. The booster group also had better general functioning at 7, 12, and 24 months, with fewer relapses, and the booster group appeared to have a slower relapse rate. We concluded that the effects of ICBT is sustained up to 2 years after completed treatment and that adding an Internet-based booster program can prevent relapse.

The eCentreClinic Program

Pilot Study

The eCentreClinic OCD Course was initially tested in a feasibility study, which consisted of 22 individuals in an open trial format1 (Wootton et al. 2011a). In this study, participants completed 8 modules over an 8-week period and received twice weekly phone calls from a registered clinical psychologist. Overall, 81 % of the participants completed the program within the 8 weeks and participants improved significantly on the Y-BOCS from pretreatment to posttreatment and from pretreatment to 3-month follow-up. Within-group effect sizes were large from pretreatment to posttreatment (d = 1.52) and from pretreatment to 3-month follow-up (d = 1.28). The intervention required on average 86 min of clinician time per participant across the 8 weeks (approximately 10 min per week). Similar to the KI program, most participants (96 %) had received a previous treatment for OCD in the past. This study provided preliminary evidence for the efficacy of the eCentreClinic OCD Course.

Randomized Controlled Trial

The initial feasibility study was later replicated and extended in a 3-group RCT comparing ICBT, bibliotherapy-based CBT (bCBT), and a waitlist control group (Wootton et al. 2013). In this study, 56 participants completed 5 modules over an 8-week period and received twice weekly phone calls from a registered clinical psychologist. The mean number of modules completed within the 8 weeks was 4.30 in the ICBT group and 4.33 in the bCBT group. Participants in both of the active treatment groups demonstrated significant reduction on the Y-BOCS at both posttreatment and 3-month follow-up, and there were no significant differences between the groups. Within-group effect sizes were large from pretreatment to posttreatment for both the ICBT and bCBT groups at posttreatment (ICBT, d = 2.16; bCBT, d = 1.65) and 3-month follow-up (ICBT, d = 1.28; bCBT, d = 1.29). At posttreatment, effect sizes between the active treatment groups and the control group were large (ICBT, d =1.57; bCBT, d = 1.40) and there was a small nonsignificant between-group effect size between the ICBT and bCBT group (d = 0.17). Forty-seven percent of participants in the ICBT group and 40 % of participants in the bCBT group met conservative criteria for clinically significant change at posttreatment, which reduced to 27 % in the ICBT group and 20 % in the bCBT group at 3-month follow-up. The ICBT intervention required 89 min of clinician time and the bCBT program 102 min of clinician time on average (a nonsignificant difference) (Wootton et al. 2013). This study provided further evidence for the efficacy of ICBT for OCD and demonstrated that therapist-guided remote treatments, delivered via the Internet or bibliotherapy, appeared equally efficacious.

Reduced Clinician Contact

At the conclusion of the active treatment in the abovementioned RCT, the waitlist control group commenced active treatment. Participants in this group completed the same ICBT program (5 lessons over 8 weeks); however, the clinician contact was reduced to once a week in order to test the efficacy of reduced clinician contact. In this study, 59 % of the 17 participants completed the program within the 8 weeks and effect sizes were large from pre- to posttreatment (d = 1.11) and pretreatment to 3-month follow-up (d = 1.50). Thirty-three percent met conservative criteria for clinically significant change at both posttreatment and 3-month follow-up. The reduced contact meant that only 57 min of therapist time was required on average to complete the intervention across the 8 weeks (approximately 7 min per week per client) (Wootton et al. 2013); however, the outcomes were similar to the more intensive treatment. This study demonstrated that weekly contact also resulted in significant and clinically meaningful gains.

Self-Guided Treatments

While it is hypothesized that ICBT reduces barriers to accessing treatment, many patients may be reluctant to engage with therapist-guided treatments, as stigma is a major barrier to accessing treatment for individuals with OCD (Belloch et al. 2009; Marques et al. 2010). For this reason, the eCentreClinic team has commenced an investigation of the efficacy of self-guided ICBT for OCD and we have now completed two open trials demonstrating the efficacy of self-guided administration of the eCentreClinic OCD program (Wootton et al. 2014). In the first self-guided study, we used the same protocol as the previous RCT (5 lessons delivered over 8 weeks). There was no pretreatment clinician contact and participants were entered into the study based on scores on the self-report Y-BOCS (a score of ≥16 was required for study entry). Forty-four percent of the 16 participants completed the program and there was a significant decrease in symptoms from pretreatment to posttreatment (effect size, d = 1.05) and from pretreatment to 3-month follow-up (effect size, d = 1.34). In addition, 19 % of participants met criteria for clinically significant change at posttreatment and 29 % at 3-month follow-up. While these results were promising, the completer rates were lower than that seen in our previous studies (e.g., 81 % in the first open trial) (Wootton et al. 2011a) and the number of participants meeting criteria for clinically significant change was slightly lower than our guided studies (33–47 %) (Wootton et al. 2014; Wootton et al. 2013; Wootton et al. 2011).

We hypothesized that participants may benefit from additional time to complete the program and practice their ERP tasks. For this reason, in the second self-guided study, we extended the treatment to 6 lessons delivered over 10 weeks. Again, there was no pretreatment clinical contact and participants were accepted into the study based on their responses on the self-report Y-BOCS (a score of ≥16). The results appeared improved over the first open trial with 64 % of the 33 participants completing the program within the study timeframe and a within-group pretreatment to posttreatment effect size of d = 1.37 and pretreatment to 3-month follow-up effect size of d = 1.17. In addition, 36 % met criteria for clinically significant change at posttreatment and 32 % met criteria at 3-month follow-up (Wootton et al. 2014). While replication and extension in an RCT are required and currently underway, it appears that self-guided treatments may be acceptable and efficacious for some individuals with OCD, especially those who cite stigma as their major barrier to commencing treatment.

Long-Term Outcomes in Self-Guided Treatment

Finally, the eCentreClinic team has recently obtained preliminary 12-month follow-up results from the second self-guided open trial. Results from this study indicate a large effect size on the Y-BOCS from pretreatment to 12-month follow-up (d = 1.08) for people who returned their questionnaires, and a moderate effect size when carrying forward the participants’ last available observation for those who did not return their questionnaires (d = 0.65). However, only 43 % of original participants returned questionnaires and further research is required to understand the long-term outcomes of self-guided ICBT for OCD (Wootton et al. 2015).

“Internet-Based Therapist-Guided Writing Therapy,” Germany

Pilot RCT

The Internet-based therapist-guided writing therapy program was initially studied in an RCT comparing active treatment with a waitlist control group (Herbst et al. 2014). Thirty-four participants were randomized and a large between-group effect size (d = 0.82) was found at posttreatment (Herbst et al. 2014). When all results were pooled (after the waitlist group commenced treatment), large within-group effect sizes at posttreatment (d = 0.83) and follow-up (d = 0.89) (Herbst et al. 2014).

The OCFighter ™ Program

Pilot Study

In the only trial conducted to date, 26 participants completed the OCFighter program in an open trial, and participants were contacted nine times across the 17 weeks of the study. The clinician contact in this study mirrored that reported in the previous Kenwright et al. (2005) BTSteps study. Two participants did not commence the treatment and a total of 17/24 (71 %) completed the 17-week program. Results indicated clinically significant reductions in symptoms on the Y-BOCS from pretreatment to posttreatment and large effect sizes on the clinician-administered Y-BOCS were seen (d = 1.15) (Diefenbach et al. 2015). This study demonstrates the preliminary efficacy of the OCFighter program; however, further controlled trials are needed.

Case Description

Mr J. was a 45-year old man who participated in one of the KI trials in Sweden. Mr J. presented with severe OCD (31/40 on the Y-BOCS) and presented with anxiety eliciting obsessions about becoming contaminated from germs and washing/cleaning compulsions (he washed his hands up to 100 times per day). Mr J. reported that he had been on a disability pension for the last 10 years due to OCD, depression, and severe alcohol abuse. However, at the time, he commenced treatment he did not meet criteria for depression and had been sober the past 2 years. Mr J. was currently living in a group home with daily support from personnel (e.g., taking walks outside, planning daily activities). Mr J. applied to our study after seeing a newspaper advertisement and, when considering the history of alcohol abuse and depression and his social situation in general, we first hesitated to include him in the ICBT study. However, he did not fulfill any exclusion criteria and was thus included in the study. Mr J. had no difficulties reading and writing and he was familiar with the use of the Internet. He completed modules 1–4 within 2 weeks and he decided to work with what he referred to “the cold turkey method” (i.e., completely refraining from all rituals). He did this for 1 week and had daily email correspondence with his therapist during this time. The therapist contact was intensive with about 3–4 emails being sent per week. At week two, Mr J. also conducted planned exposures in his apartment and at other places in addition to his complete response prevention. At mid-treatment, Mr J. felt he had made some substantial progress and the rest of the treatment focused on higher level exposure tasks such as dating and meeting with friends, which he had previously avoided because of both contamination concerns and low mood. Mr J. had a Y-BOCS score of 3 at posttreatment, 1 at the 3-month follow-up, and 0 at the 12-month follow-up. Although this may not be the typical patient in ICBT, it demonstrates that anyone can potentially benefit from ICBT even those patients who, at first sight, may not seem appropriate for remote treatment.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree