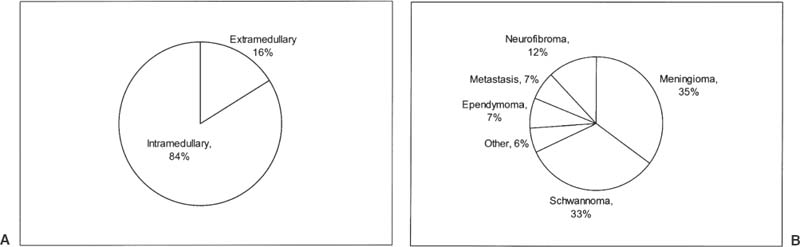

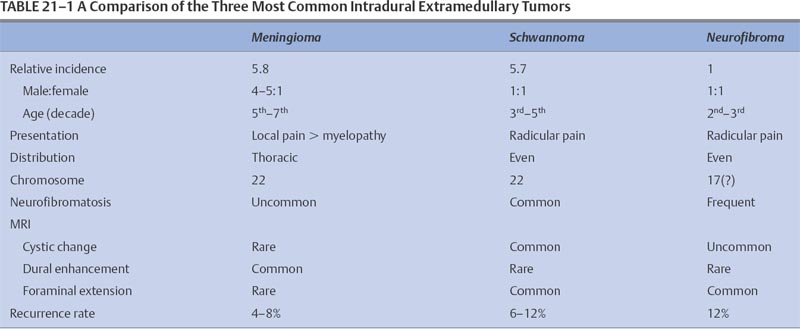

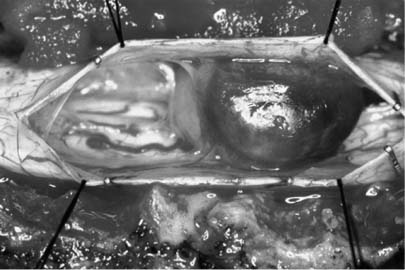

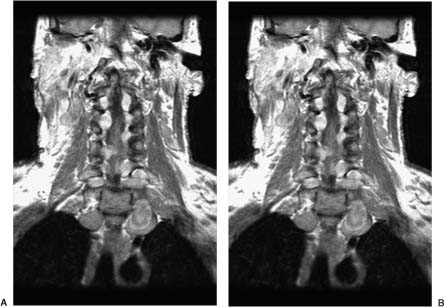

21 Ever since the first reported removal of an intradural extramedullary spinal tumor in 1887, resection of these largely benign lesions has been a source of satisfaction for neurosurgeons. With advances in preoperative imaging and refinements in microsurgical techniques, the surgical management of these lesions has resulted in a high rate of complete resection and a low rate of complications. Of the tumors in this compartment of the spinal canal, at least 80% are schwannomas, neurofibromas, and meningiomas. The relative frequency in a series of 1322 patients with intradural spine tumors at the Mayo Clinic was 29% nerve sheath tumors, 26% meningiomas, 22% gliomas, and 12% sarcomas, with the rest being hemangioblastomas, chordomas, and epidermoids1 (Fig. 21-1). Although tumors of the intradural extramedullary space comprise 60% of all spinal tumors in adults, they account for only 10% of spinal tumors in children. As most surgical series are hampered by a major selection bias, it is difficult to determine the true incidence of these tumors. A study performed decades ago found that in Iceland, where records are extensive and exact, the incidence of intradural spine tumors was 1.1 per 100000, an incidence nine times less than that of intracranial tumors.2 FIGURE 21-1 The relative incidence of (A) intramedullary and extramedullary tumors, and (B) various tumors of the intradural-extramedullary compartment in adults. The signs and symptoms of intradural extramedullary neoplasms are not specific to this spinal compartment and may be caused by a variety of other conditions such as spondylitic myelopathy, multiple sclerosis, and extradural spinal tumors. Due to the slow growth, most of these tumors display a considerable period of symptomatology that may persist prior to diagnosis. The most common symptom is pain, either localized or radicular. Schwannomas or neurofibromas originate from spinal roots and thus present with radicular pain in up to 80% of patients.3 Meningiomas, which arise from the dura, tend to present with a myelopathic syndrome or localized back pain more commonly than with radicular pain.4–6 Ependymomas of the filum terminale typically present with localized back pain that progresses to bilateral leg pain.7 Tumors of the cauda equina have been said to classically present with pain on recumbency that improves while standing; however, this may also be seen with intramedullary lesions and is presumably due to pressure changes in the epidural venous plexus.6 The classic three stages of (1) spinal cord compression, root pain, or segmental sensory or motor disturbances, followed by (2) Brown-Séquard syndrome, and progressing to (3) transection of the spinal cord are rarely seen in these times of widely available imaging, except perhaps in the instance of rapidly growing tumors. The more typical slowly growing tumors of this location more commonly present with an indolent onset of symptomatology. Up to 80% of patients with spinal meningiomas present with upper motor neuron findings; however, nearly 70% are ambulatory at the time of diagnosis.5,8 Signs may be subtle and may only be manifest as alterations in coordination or in fine movements. Sphincter function may be altered in 15% of cases, although this finding is more common with lesions affecting the conus.1,9 Subjective sensory complaints are common but may be difficult to demonstrate objectively. In advanced cases a sensory level may exist, but this is becoming a less common finding now that patient access to early imaging, including the wide availability of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), has improved. Extramedullary tumors most commonly present with alterations of all sensory modalities, whereas intramedullary tumors tend to spare the posterior columns and present with a dissociated sensory loss that may be suspended between areas of normal sensation above and below.1 Plain x-rays may demonstrate enlarged neural foramina, thinned pedicles, increased interpeduncular distance, and scalloping of the posterior vertebral body, particularly with schwannomas and neurofibromas.10,11 These findings are mainly seen with large lesions and advanced disease; however, with readily available MRI the identification of findings on plain x-ray is becoming less and less common. Conventional myelography demonstrates the level of the lesion and its relationship to the spinal cord and dural sheath. On myelograms intradural extramedullary lesions show a rostral and caudal “cap,” and the anterior-posterior relationship to the spinal cord will be evident. Extramedullary lesions have a “paintbrush” pattern on myelography with a complete block of the spinal canal but demonstrate an “hourglass” appearance with a partial block. Intramedullary lesions appear as a fusiform dilatation of the spinal cord without a complete block. Computed tomography (CT) myelography has all but replaced conventional myelography and demonstrates not only the bony anatomy but also the plane between the tumor and spinal cord quite readily. Some authors feel that CT myelography is as good as MRI in demonstrating intradural pathology, but given new MRI techniques, this is no longer the case.6 In the occasional patient who is unable to tolerate MRI or in whom MRI is contraindicated, such as those with ferromagnetic aneurysm clips or cardiac pacemakers, CT myelography remains the primary diagnostic modality. Magnetic resonance imaging is currently the preferred imaging modality for tumors of the spinal canal. The quality of the images obtained with and without gadolinium distinguishes lesions in the intradural extramedullary space from tumors in the other spinal compartments in most cases. Although not definitive, certain features on MRI may be utilized to discriminate partially among the most common lesions in the intradural extramedullary space, as will be discussed in the following sections. Angiography is not routinely performed but is useful in cases where vascular pathology, such as an arteriovenous malformation or dural arteriovenous fistula, is suspected. For tumors of the cervical canal, the vertebral artery should be evaluated if the bone around the canal surrounding the vertebral artery (foramen transversarium) is involved with tumor. For tumors of the intradural extramedullary space, embolization is rarely required but may be considered for suspected hemangioblastomas or meningiomas.6 Meningiomas of the spinal canal arise most commonly in the fifth to seventh decades of life and have a striking female predominance, with only 20% occurring in males.5,8 Meningiomas may grow during pregnancy12,13 and have been linked with breast carcinoma.14 These associations may be related to a putative hormonal influence on growth operating through progesterone receptors, which are expressed by most meningiomas.15 Even after accounting for the relative length of the thoracic spinal canal, a disproportionately high number of these lesions occur in the thoracic spine (75%), with the next most common site being cervical (20%)5,6; meningiomas in the lumbar spine are unusual.16 The propensity to involve the thoracic spine seems to be true only in females, as the relative involvement of the thoracic and cervical levels is approximately equal in males, once the length of the spinal segment is accounted for.17 See Table 21-1 for a comparison of the three most common tumors of the intradural extramedullary space. Meningiomas arise from arachnoidal cap cells adjacent to the dura near the nerve root sleeve but may also arise from dural fibroblasts or from the pia, which may account for purely dorsal or ventral presentations as well as intramedullary meningiomas.18 Apart from the rare instances just stated, meningiomas usually arise laterally within the spinal canal and may be most commonly anterolateral above C7 and posterolateral below.17 Up to 15% involve both the intradural and extradural spaces or are purely extradural.4,8,19 These extradural tumors are notable as they are more common in males, are more aggressive, and may adhere to surrounding structures.19,20 Spinal meningiomas are variegated and fleshy in appearance and are generally less vascular than their intracranial counterparts.6 En plaque forms are unusual in the spinal location. There are multiple subclassifications of meningiomas; however, the most common spinal variants are meningothelial and psammomatous.4,5 The were no malignant tumors in a review of 97 spinal meningiomas from the Cleveland Clinic.17 Most occur in one site, but multiple tumors may be found in patients with neurofibromatosis. Up to 60% of sporadic meningiomas have been found to carry mutations in the NF2 gene on chromosome 22,21 although these mutations seem to be less common in meningothelial variants.22 Meningiomas tend to be most commonly isointense to spinal cord on both T1 and T2 MRI sequences with homogeneous enhancement with gadolinium4,23 (Fig. 21-2). In contrast to other lesions of the intradural extramedullary space, meningiomas can demonstrate a “dural tail” sign of dural enhancement, which some authors have suggested is highly typical and best seen on coronal images.24 In addition, meningiomas tend to enhance less after contrast administration compared with schwannomas and neurofibromas, and rarely exit the neural foramen.23 Therapy should be directed toward an attempt at gross total resection; however, this may not be possible and may even be dangerous in calcified or anteriorly situated tumors17 (Fig. 21-3). Aggressive excision of involved dura does not result in a lower recurrence rate than dural coagulation alone and may result in a higher complication rate.5,8 Complete resections are possible in 82 to 97% of cases with current microsurgical techniques.4,20 Overall, spinal meningiomas appear to be less aggressive than their intracranial counterparts. They show a 4 to 8% long-term recurrence rate with a mean time to recurrence of 5 years,5,8,20,25 although recurrences up to 38 years after removal have been reported.26,27 Subtotally resected lesions may not grow for many years and have a recurrence rate of <15%.8 Progression-free survival for gross total resections has been reported to be 93%, 80%, and 68% at 5, 10, and 15 years, respectively, whereas for subtotal resections the rates are 63%, 45%, and 9%.28 Radiotherapy is reserved for recurrent tumors that cannot be completely resected and for malignant forms, which are rare in the spine. Significant recovery may be expected postoperatively, with 80 to 90% of patients with incomplete neurologic deficits showing improvement, even when the impairment is long-standing.4,5 FIGURE 21-2 A meningioma arising at T5–T6 posterolaterally and displacing the spinal cord. FIGURE 21-3 Intraoperative photograph of a thoracic meningioma that is well circumscribed and completely separate from the spinal cord. These common neoplasms arise from Schwann cells of the posterior spinal roots, but they may occasionally arise from a motor (anterior) root as well. Nerve sheath tumors account for up to 30% of all spinal neoplasms in some series and have roughly the same incidence as meningiomas. Except in the setting of neurofibromatosis, schwannomas account for approximately 85% of nerve sheath neoplasms.3 In contrast to meningiomas, they occur equally in males and females, have a relatively even distribution over the spinal column, occur in younger populations, and are usually discovered during the third to fifth decades of life.6,18 Schwannomas are typically smooth globoid masses with a tan color, without significant vascularity on the surface of the tumor, and they tend to arise from a single fascicle and not involve the remainder of the nerve root to a significant degree.29 As these neoplasms arise from the posterior spinal roots, they are thus found posterolateral to the spinal cord.6,18 Rarely, schwannomas may be intramedullary, presumably arising from peripheral nerve sheath elements around the penetrating branches of the anterior spinal artery.30 Thus, schwannomas may involve multiple spinal compartments, including the intradural extramedullary (72%), extradural (13%), intradural and extradural (13%), and intramedullary (1%) spaces.18 Patients with certain genetic conditions are predisposed to schwannomas. The hallmark of neurofibromatosis type 2 (NF2) is bilateral vestibular schwannomas, although these patients are also prone to developing peripheral and spinal schwannomas with increased frequency.31 The NF2gene, located at chromosome 22q12, is thought to be a tumor-suppressor gene and is also altered in over 50% of sporadic schwannomas.31–33 Other conditions with predispositions to spinal schwannomas include schwannomatosis34 and Carney’s complex.35 Patients with Carney’s complex may have facial pigmentation, cardiac myxomas, endocrine overactivity, and melanotic schwannomas, of which 10% are malignant.36,37 On MRI scans, schwannomas are iso- or hypointense to spinal cord on T1 sequences and have increased signal on T2 sequences38 (Fig. 21-4). Focal areas of markedly increased T2 signal may indicate cystic change, whereas areas of lower T2 signal may represent hemorrhage or collagen formation.39 Cystic changes, lack of dural enhancement, or increased peripheral enhancement in schwannomas may help differentiate these lesions from meningiomas that only rarely demonstrate these findings.24,38 FIGURE 21-4 Sagittal (A) and axial (B) magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrating a contrast-enhancing schwannoma at L1–L2. The goal of surgery for schwannomas is complete removal. It may be possible to separate the involved fascicle from the rest of the nerve root and thus preserve the majority of the root. Even after partial resections, symptomatic recurrences may not occur until many years later.40 If no separate fascicle can be identified, it is often most prudent to resect the fleshy internal portion of the tumor while leaving its peripheral capsule intact. This preserves root function while assuring relief of local mass effect against the adjacent spinal cord, and the tumor remnants can sit dormant for many years in some patients; however, neurofibromatosis has a profound effect on the recurrence of schwannomas, with a 39% recurrence rate at 5 years with neurofibromatosis and 11% in those without.41 Other authors have reported recurrence rates of 6 to 12% with a mean time to recurrence of 4 years, not including cases of neurofibromatosis.25,40,42 Neurofibromas may arise in patients with neurofibromatosis or sporadically, unrelated to a clinical syndrome. They account for 15% of nerve sheath tumors.3 Up to 60% of cases occur in the setting of neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1).43 As well, an estimated 55% of patients with NF2 have intradural extramedullary tumors.44 As with schwannomas, males and females are equally affected, and the relative incidence among spinal levels is proportional to the length of the segment, with the thoracic spine the most common location.17 The majority of neurofibromas are entirely intradural; however, 30% of them have an extradural component, with half of these being both intra- and extradural and half entirely extradural.3,17 The cell of origin of these tumors is uncertain; it is not likely to be the Schwann cell but, rather, a cell of the mesenchymal line.6 Patients with NF1 have mutations on chromosome 17q12, and this gene may also be involved in the formation of sporadic neurofibromas.45 In patients with NF1, nerve root tumors are most commonly neurofibromas but can be schwannomas.46 Although malignant degeneration is only rarely seen in sporadic tumors, it develops in 5 to 10% of neurofibromas in patients with neurofibromatosis and is usually heralded by a rapid increase in pain and in size of the lesion. Larger tumors are more prone to such transformation. These tumors arise most commonly from the central root and develop as a fusiform enlargement of the nerve, making it nearly impossible to separate surgically from the tumor without sacrificing the root. The MRI appearance of these lesions is similar to schwannomas; however, cystic change is uncommon in neurofibromas38 (Fig. 21-5). FIGURE 21-5 Coronal MRI scans (A) showing neurofibromas at nearly all levels of the spine, some of which extend through the intervertebral foramina, and (B) demonstrating the serpiginous nature of the spinal cord due to the presence of multiple neurofibromas. Successful therapy requires an attempt at gross total resection, which may involve sacrifice of the involved nerve root; however, this is generally not accompanied by a significant alteration of neurologic function17 (Fig. 21-6). Complete relief of pain can be expected in over 85% of patients, even in those undergoing partial resections.17 The recurrence rate has been estimated to be approximately 12%.3

Intradural Extramedullary Spinal Tumors

Clinical Presentation

Clinical Presentation

Imaging

Imaging

Meningiomas

Meningiomas

Schwannoma

Schwannoma

Neurofibromas

Neurofibromas

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree