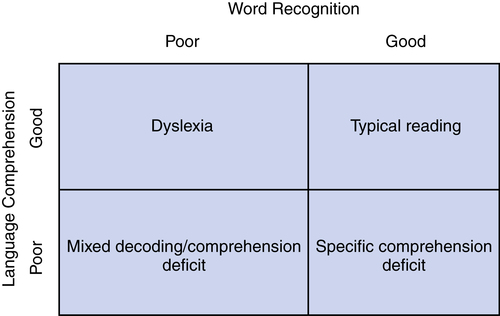

Chapter 10 Readers of this chapter will be able to do the following: 1. Name roles and responsibilities of school-based speech-language pathologist (SLP) practice. 2. Describe the major acts of legislation that govern practice in schools; and describe their implications for practice. 3. Recognize documents critical to school-based SLP practice. 4. Discuss the role played by SLPs in early intervening and responsiveness to intervention models of instruction. 5. List the characteristics of school-aged children with language and learning deficits. 6. Describe connections among oral language, learning, and literacy. 7. List similarities and differences in oral and written language. 8. Identify effective strategies for promoting literacy through oral language support and instruction. Nick is a child whose oral language sounds normal to the “naked ear.” He does not make many obvious errors in phonology or syntax, although he did when he was younger. Now his problems with communication are subtler and harder to define, but they seem to have a significant impact on his ability to acquire the skills needed for success in school. There are many children like Nick in our school classrooms, and they often come to the attention of the speech-language pathologist (SLP) through “early intervening” and responsiveness to intervention (RTI) procedures. Some, like Nick, have histories that suggest a possible root of their problem. Others have no such history, but simply have difficulty meeting the demands of the school curriculum for no apparent reason. Some may have started speaking late, have shown delays in acquiring words, combining words into sentences, or pronouncing the sounds of speech. Others have had unremarkable preschool language histories but seem to “hit a wall” when it comes to making the transition from oral to written language. Regardless of their language history, these children are beyond Brown’s stage V in terms of their vocabulary and sentence structures. They may be classified as learning disabled, reading disabled, or dyslexic, or they may have no diagnosis but have been identified in RTI (see Chapter 3) programs or been recommended for “early intervening services” in areas of language and literacy to prevent school failure. Here in Section III, we focus primarily on children who, despite otherwise apparently typical development, struggle to succeed in the acquisition of literacy. Many of these children fall under the broad rubric of language-learning disability (LLD). This term implies that students have difficulty with various aspects of communication that interfere with their ability to succeed in school. Other children the SLP will encounter may not have an identified disability, but will fail to make adequate progress in the regular curriculum and will need some support to prevent them from falling so far behind peers as to eventually be diagnosed with a learning disability. Both these types of children, though, will have mastered the basic vocabulary, sentence structures, and functions of their language but have trouble progressing beyond these basic skills to higher levels of language performance in both oral and written modalities. In Chapters 11 and 12, we will talk about the role of the SLP in promoting both language and literacy development for such students during their elementary school years, from kindergarten through fifth or sixth grade, when normally developing children are between 5 and 12 years of age. In Chapters 13 and 14, we will look at adolescents with LLDs in secondary school settings. There are, of course, children in schools whose communicative skills are still in the developing, emerging, or prelinguistic levels. Some of these students will be placed in resource rooms or special education classes, and others in inclusive settings. SLPs who work in school settings will find these children, too, included in their caseload. In fact, one of the exciting things about working in schools is the wide variety of issues and levels of functioning the SLP encounters. Thanks to legislation that mandates free, appropriate public education (FAPE) to all children, those with every type and severity of communication disorder will go to public schools along with their peers. Although specific methods for use with the broad range of disabilities seen in school settings are not addressed in this chapter, principles for addressing the needs of school children at earlier stages of communication can be found in Chapters 6 through 9. However, because SLP practice in schools involves work with individuals at all points on the spectrum of communicative function, as well as knowledge of the legal and professional issues specific to school-based practice, we will preface our more focused discussion on language/literacy issues for this stage of development by examining some of the issues that affect practice with all our students in school settings. SLPs, as part of the educational team that delivers comprehensive services to students with disabilities, provide a wide array of supports to their clients in schools. The American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA, 2010) has recently redefined our roles and responsibilities to reflect the broad range of activities appropriate for SLPs who practice in school settings. These appear in Box 10-1. SLPs who work in schools are guided by federal laws that regulate special education. The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) of 1997 (reauthorized in 2004) is the major piece of legislation that applies to this work. Part B of IDEA specifies how services are to be provided for children aged 3 to 21. The specific diagnostic categories recognized as requiring special education appear in Box 10-2. Where earlier special education laws had been concerned with ensuring access to FAPE in the least restrictive environment (LRE) and providing Individualized Educational Plans (IEPs) for all children, the 1997 act and 2004 reauthorizations shifted to emphasize accountability for meaningful educational results by: • Increasing parental participation • Identifying student strengths and parental concerns • Raising expectations for children with disabilities by relating student progress to the general education curriculum • Ensuring that all children have scientifically-based, appropriate instruction in reading • Including regular education teachers in the special educational team • Including children with disabilities in district-wide assessments and reports • Supporting high standards for professionals involved in service provision • The requirement that schools show adequate yearly progress (AYP) on tests and graduation rates • Permission for school to spend up to 15% of special education funds to support students in the general curriculum • Standards for reading instruction Another law that pertains to practice in schools is Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973. It guarantees equal protection for individuals with physical or mental disabilities. Although it does not provide funding for services, it does require accommodations to allow students to participate in general education, such as physical access to school buildings for students in wheelchairs, assistive listening devices, and extra time to complete tests and assignments. Children with 504 plans do not receive an IEP; and generally such plans are used to support children who do not qualify for one of the twelve diagnoses listed in Box 10-2. Often, for example, children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder who do not have other disabilities will be accommodated by means of 504 plans. Many school systems today use the RTI (see Chapter 3 for definition and further discussion) model, particularly in the primary grades, to attempt to resolve learning problems within the regular education setting, by providing classroom modifications and accommodations that can prevent the need for special education or for labeling a student as having a special educational need. RTI approaches are most often seen in the area of literacy instruction in the primary grades (Fuchs & Fuchs, 2009), although their use in other curricular areas and age levels is expanding (see, for example, Ehren & Whitmire, 2009; Justice, McGinty, Guo, & Moore, 2009; Montgomery, 2008). As we saw in Chapter 3, RTI uses a three-tiered structure (National Joint Committee on Learning Disabilities, 2009): Tier I: High quality, scientifically research-based classroom instruction for all students in general education, with ongoing, curriculum-based assessment and continuous progress monitoring. Tier II: Students who lag behind peers receive small group, more specialized instruction to prevent failure within general education. Tier III: For students who continue to struggle after provision of intensified, small group instruction in Tier II, individualized instruction may be provided; if adequate progress is not made, comprehensive evaluation is conducted by a multidisciplinary team to determine eligibility for special education and related services. RTI, then, is aimed at prevention of reading disability. Implementation of RTI provides a number of important roles for SLPs. Ehren, Montgomery, Rudebusch, & Whitmire (2009) suggest that SLPs in RTI settings can make unique contributions by (1) participating, through their knowledge of the connections between oral language and literacy, in the design of Tier I instruction by planning and conducting professional development on the language basis of literacy, helping to select scientifically based literacy instruction programs, and choosing appropriate screening and progress-monitoring approaches; (2) collaborating with general education teachers in presenting Tier I instruction, assisting with ongoing progress monitoring, and helping teachers develop accommodations within Tier I for struggling students; and (3) serving students by providing small group and individual instruction at Tiers II and III, and using a range of assessments from tests to observational methods to identify struggling students and monitor progress. While RTI involves changes from the way SLPs have traditionally operated in school settings, it provides opportunities, as well: opportunities to use more pragmatic, authentic assessment procedures to identify children having difficulty, to work more closely with general education teachers on ways to enhance language and literacy skills not only for children with special educational needs, but for students for whom school failure can be prevented with just a little extra “boost” early in their school careers, and to allocate time for indirect services such as supporting classroom teachers and others who work with children before referrals for special education happen. All these opportunities give SLPs the chance to be a more highly visible, integrated member of the school success team. Still, SLPs will continue to be responsible for the communication skills of all children in public schools, such as those with intellectual disability, autism spectrum disorder, hearing impairment, and severe speech impairments. As Ukrainetz (2006) pointed out, SLPs may find their services needed both by students with recognized special needs and by students needing support within an RTI model, as a preventive measure. SLPs in work in settings that demand these dual roles may need to make adjustments in the organization of their delivery of services. We’ll talk about some of these options in Chapter 12. One responsibility of the school SLP is to decide whether a student referred for speech-language services meets district eligibility criteria. Eligibility criteria, though, vary not only from state to state but in some cases from school district to school district. Just as we learned in Chapter 1 that there is no universally accepted definition of language disorder, there is no universally accepted criterion of eligibility for communication services in schools. Some states require a test score that is two or more standard deviations below the mean; others require two test scores that are 1.5 standard deviations below the mean, some a combination of test performance and severity rating, and so on (Moore-Brown & Montgomery, 2001). In districts that employ RTI, a student may be required to be tried at all three RTI levels before a referral for special education can be made. Moreover, IDEA requires that whatever impairment the child has must adversely affect academic performance if services are to be provided. This requirement is interpreted rather broadly, though. Whitmire and Dublinske (2003) show that, because many state standards for academic proficiency include speaking and listening skills, children who have language problems may qualify for special educational services, even if their academic achievement is not significantly depressed by their communicative disorder. For example, even though residual speech errors on late-developing sounds such as /s/, /r/, and /l/ do not to carry great risk for literacy problems (Bishop & Clarkson, 2003), the presence of “speech/language impairment” as one category of disability eligible for special education services suggests that SLPs may include children with residual errors on caseloads, particularly if the errors affect social opportunities and acceptance. SLPs need to become familiar with the eligibility requirements and local proficiency standards of the school districts in which they are employed and learn to use these standards to find ways to provide services for all children with communicative needs. Once a child has been identified as having a special need in the area of communication, the next step is to establish goals and objectives to meet these needs, as identified in the assessment. These goals and objectives are incorporated into the IEP, which contains the components listed in Table 10-1. TABLE 10-1 Required Components of the Individualized Educational Plans Adapted from Moore-Brown, B., Montgomery, J., Bielinski, H., & Shubin, J. (2005). Responsiveness to intervention: Teaching before testing helps avoid labeling. Topics in Language Disorders, 25(2), 148-167. 1. The direction of the intended change (increase/decrease/maintain) 2. The area of deficit (e.g., reading comprehension) or excess (e.g., articulation errors) 3. The present level of performance (e.g., at fifth percentile for grade on word reading) 4. The expected annual ending level of performance (e.g., performs at 20th percentile for grade on word reading) 5. The resources needed to accomplish the expected level of performance (e.g., one-to-one instruction; consultation with classroom teacher) 1. Conditions: the circumstances under which the behavior will be performed (“after identifying its story elements with the SLP;” “given a list of ten words and a list of meanings selected from science units”) 2. Description of specific behavior (“Nick will complete a book report on a book chosen in collaboration between the teacher and the SLP;” “James will match the word to its meaning”) 3. Criterion for measuring success or attainment of the goal (“that includes at least four of the five elements required for the class assignment;” “with 90% accuracy”) 4. Evaluation procedure: the way the goal will be measured (“as measured by improvement in grades on book report assignments;” “as measured on end of unit tests”) Benchmarks describe the amount of progress a student is expected to make during each segment of the school year. They translate grade level standards into concrete things the student should be able to do and understand and mark progress toward the achievement of curricular standards. Each benchmark may contain several indicators, which describe what students will be able to do without teacher assistance on the way toward accomplishing the goal. Both STOs and benchmarks are used to specify the sequence of specific measurable behaviors that will be observed as a student makes progress from the current level of performance to the annual goal (O’Donnell, 1999). A more colloquial definition would be that LDs involve an unexpected difficulty, relative to age and other abilities, in learning in school. Unexpected is usually taken to mean that there is no obvious explanation for the child’s difficulty. So, as the IDEA definition states, the child may or may not have a hearing impairment, intellectual disability, emotional disturbance, autistic disorder, motor deficit, or lack of opportunity or experience, but even if these are present, they would not be sufficient to explain the learning problem. Many definitions of LD have traditionally included a discrepancy criterion. That means that eligibility for the label involved a significant discrepancy (and we saw in Chapter 1 how hard that is to agree upon!) between potential (usually meaning IQ) and achievement (usually measured by a standardized test of school performance) or between areas of development, such as between verbal and nonverbal IQ. The discrepancy criterion has now fallen out of favor, for many of the reasons we talked about in Chapter 1. In fact, in the 2004 reauthorization of IDEA, the law specifically states that a discrepancy between test scores does not have to be the criterion for eligibility for LD. LEAs may, under the new law, choose a different criterion, such as lack of response to scientifically-based instruction. This provision of IDEA has opened the door for the use of RTI as a method both of preventing academic failure and as a means of identifying children with learning disabilities. Another term in common use for the disorders we are calling LLD is reading disorder, or RD. Catts and Kamhi (2005b) use this term to refer to a heterogeneous group of poor readers whose weak language skills play a causal role in their reading difficulty. The “simple view” of reading (Kahmi, 2009), the view most prevalent among reading researchers today, holds that these reading disorders can be divided into two basic classes, as depicted in Figure 10-1. There we can see that children are given the label dyslexia when they have a deficit that primarily affects their ability to decode, or to translate letters into their corresponding sounds and synthesize the sounds to form words. The National Institute of Child Health and Development adopted this definition of dyslexia (Lyon, Shaywitz, & Shaywitz, 2003): Contemporary summaries of the current state of research on dyslexia (Pennington & Bishop, 2009; Pennington & Lefly, 2001; for reviews, see Catts & Kamhi, 2005b; Goswami, 2009; Pennington & Bishop, 2008; Pugh & McCardle, 2009; Ramus & Szenkovits, 2009; Scarborough, 2003; Shaywitz & Shaywitz, 2005; Snow, Burns, & Griffin, 1998; Snowling, 1996; Snowling & Hayiou-Thomas, 2006; Snowling & Stackhouse, 1996; Vellutino et al., 2004; Vellutino, Fletcher, Snowling, & Scanlon, 2004) show that the root of this specific reading disorder has been quite firmly established as an inadequate ability in word identification due primarily to deficiencies in phonological skills, with the involvement of specific brain regions demonstrated through neuroimaging studies (see Frost et al., 2009; Noble & McCandliss, 2005; Shaywitz & Shaywitz, 2005 for review). Evidence for visual processing disorders as a cause of dyslexia is very weak; children with dyslexia don’t reverse words and letters visually, as has been thought in the past. Instead, their primary difficulty is in the phonological awareness, memory, and coding skills that allow children to do phonemic segmentation and synthesis tasks, and learn to use the alphabetic principle—the understanding that words can be broken down into sounds and that letters stand for sounds which can be combined to produce words—to decode print. Other deficiencies in word recognition and reading comprehension stem from this basic difficulty in cracking the alphabetic code. A wide range of studies (e.g., Bradley & Bryant, 1985; Gillon, 2005b; Liberman & Liberman, 1990; Mann & Liberman, 1984; Noble & McCandliss, 2005; Scarborough, 2003; Schuele & Boudreau, 2008; Snowling & Nation, 1997; Stackhouse & Wells, 1997) has shown that phonological awareness is highly correlated with reading ability, and that treatment for phonological awareness is associated with increases in decoding skill (e.g., Ehri et al., 2001; Gillon, 2005b; Schuele & Boudreau, 2008). Specific comprehension deficits, on the other hand, are those seen in children who typically have long-standing delays in oral language acquisition that affect their ability to comprehend language in any form, whether oral or written. These children may learn to decode in the first few grades and may manage early classroom texts normally, when their language content is simple and the demands on comprehension limited. These students run into difficulty in middle grades, when their weak oral language skills are inadequate to support the more complex content they need to process in grade-level reading material. Of course, some children may have both kinds of difficulties, as Figure 10-1 suggests. So what’s the difference between RD and dyslexia? Most current thinking, represented by Catts and Kamhi (2005a), Catts et al., (2006), Snowling (1996), Snowling and Hayiou-Thomas (2006), and Vellutino et al. (2004), holds that dyslexia is part of a continuum of language disorders. What differentiates dyslexia from a more general LLD or RD is that dyslexia involves a specific deficit in single-word decoding that is based in a weakness in the phonological domain of the oral language base and has only a secondary impact on reading comprehension. It is a disorder affecting just one aspect of the reading process: decoding. Children with LLD, on the other hand, can have problems with both single-word reading and comprehension, and not only of written language, but of oral language, as well. These comprehension problems are thought to stem from difficulties the child has not only in phonological processing but in other language domains, such as syntax and semantics. Children with more general LLDs often have a history of delayed speech and language development as preschoolers, whereas those with dyslexia often do not (Snowling, 1996). We can think of dyslexia as a specific subtype of RD, which is a common subtype of LLD. School-aged children with LLD do not necessarily have obvious errors in their speech production, and their speech is generally intelligible. A good deal of research has examined the relationship between preschool speech delay and later reading problems. Generally, findings suggest a higher prevalence of speech disorders in children with LLDs than in the general population, with about 25% of children with LLD showing delayed speech development at school age, whereas only 4% to 6% of the general population does (Kuder, 1997; Pennington & Bishop, 2009). Hesketh (2004) and Leitao and Fletcher (2004) reported that, although most children with speech delays during the preschool period make adequate progress in reading once they get to school, a small number of them develop phonological awareness and literacy delays. Snowling, Bishop, and Stothard (2000) reported that reading outcomes are poorest for children with the most severe phonological disorders. As it is for other children, phonological awareness appears to be the best predictor of literacy achievement in these speech-delayed students. Stackhouse (1996) reports that these speech difficulties primarily affect the acquisition of spelling. Still, it is important to know that both Pennington and Bishop (2009) and Peterson et al. (2009) found that reading difficulties in children with a history of speech disorders were better predicted by their language skills (speech and language difficulties often go together in young children) than by their speech. Even though children with LLD do not have significant articulation errors, they often show difficulty with speech perception, phonological memory and phonological awareness (Pennington & Bishop, 2009), as well as with complex phonological production in difficult words (such as statistics) or phrases (“Fly free in the Air Force”; Catts, 1986), or in repeating phonologically complex non-words (such as /tribabli/). Tests involving phonologically complex, multisyllabic words (such as aluminum) and unfamiliar nonsense words can be useful in identifying these children. Rvachew (2006) and Rvachew and Grawburg (2006) reported that speech-delayed children who have poor speech perception and low receptive vocabulary were at greatest risk. Rvachew advocates assessing both speech perception and vocabulary in making decisions about whether to provide intervention to prevent literacy difficulties in speech-delayed preschoolers. Children with LLD have consistently shown problems with short-term memory tasks (Catts, 1989; Snowling, 1996). Bishop (1997) and Liberman and Liberman (1990) reported, though, that these deficits are restricted to memory for verbal material. Students with LLD generally have no difficulty with memory tasks involving nonverbal stimuli or environmental sounds. Moreover, children with LLD show weaknesses in the ability to do rapid naming and in non-word repetition tasks. When asked, for example, to say all the days of the week or to repeat nonsense words, such as flipe or wid, children with LLD perform more poorly than those with normal school achievement (Larrivee & Catts, 1999; Snowling, 1996; Wesseling & Reitsma, 2001). These problems may not sound phonological at first, but researchers believe that the source of this difficulty is in establishing and retrieving accurate phonological representations (or segmenting the words into sounds, then storing sound-by-sound auditory images and retrieving these images as a template for production) of verbal material. These same problems also are thought to be related to the word retrieval difficulties so commonly seen in children with LLD.

Language, reading, and learning in school: what the speech-language pathologist needs to know

School-based practice in speech-language pathology

Laws applying to school-based services

Preassessment and referral under RTI

Determining eligibility

Writing individualized educational plans

Component

Description

Strengths & concerns

Parent concerns and priorities, as well as child’s areas of relative strength are listed.

Evaluation results

Assessment results are reported and interpreted.

Present level of educational performance

The effect of the student’s disability on participation and progress in the curriculum is reported.

Annual goals

Long-term goals related to meeting general educational curriculum or other educational needs that result from the disability are listed in each area of disability.

Short-term objective and benchmarks

Measurable, sequenced steps toward annual goals are detailed.

Amount of special education or related services

Projected beginning date, frequency and types of service, and an estimate of duration are given.

Supplementary aids and services

Describes how the regular educational program will be modified so that the child can participate, how services will contribute toward this participation in the general education curriculum, as well as in extracurricular activities. Also contains information about the types of related services needed (SLP, occupational therapy, etc.). These services may be direct, as in one-to-one therapy, or indirect, as in consultation to the classroom teacher by the SLP. Any assistive equipment the student might need to participate in the curriculum (such as a hearing aid or an AAC device) is also listed.

Participation in regular education environments (least restrictive environment; LRE)

The extent of the student’s participation with students without disabilities in both educational and extracurricular settings is given. Accommodations might be included, such as support staff to help the child succeed in the setting, modifications in transportation and equipment, and behavioral interventions to manage problem behaviors in the classroom.

Test modifications

Modifications needed to participate in district-wide assessments of student achievement are given.

Transition services

Interagency responsibilities and community links to help student move toward adult placement are listed.

Notification of transfer rights

Documentation that the student has been informed of his or her rights when maturity is reached.

Evaluation procedures and measurement methods

How and when student progress will be measured (progress must be reported as often as it is for general education students). Progress must be evaluated at least once every 3 years, although it can be done more often. Assessment may be relatively short and may use existing data or observational records. Parents also must be informed of how the child’s progress toward goals will be measured, and they must receive progress reports as least as often as children in regular education receive report cards. The reevaluation can have three possible outcomes: (1) continuation—if the student is moving toward goals as expected, the plan can be continued without changes; (2) modification—if small changes in the IEP are needed to maximize student progress but the changes are not significant enough to warrant another IEP meeting; or (3) revision—if the IEP must be rewritten with significant changes because of lack of or greater-than-expected progress that warrants the targeting of new goals or a reduction in services needed. Parents’ consent must be obtained for the program to be changed.

IEP team members

Signatures of all IEP members, including parents, general education teachers, special educators, and administrators are needed.

Annual goals

Short-term objectives and benchmarks

Students with language learning disabilities

Definitions and characteristics

Phonological characteristics

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Neupsy Key

Fastest Neupsy Insight Engine