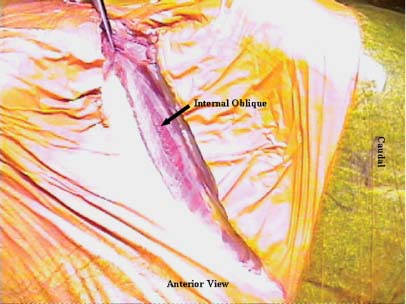

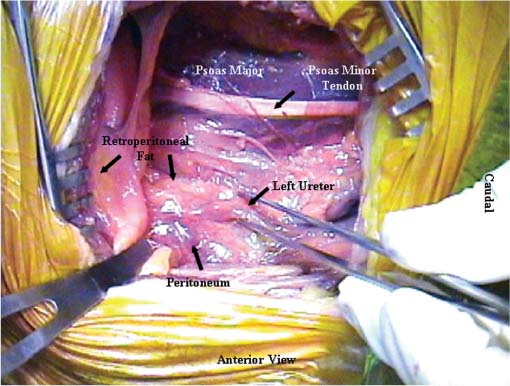

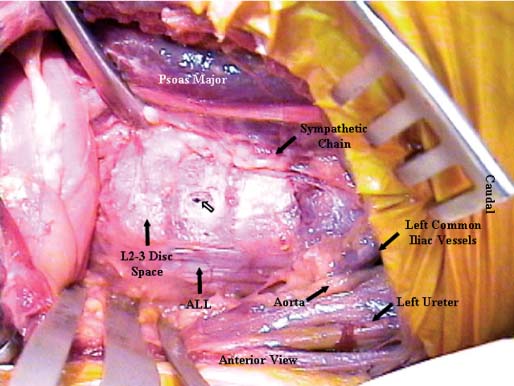

38 The flank retroperitoneal approach has been well described in the general and vascular surgery literature since the early 1800s.1 Modification of this approach for anterior lumbar spinal surgery was first performed for the treatment of tuberculosis in the 1950s.2 Since then, this approach has been utilized routinely for a wide variety of spinal disorders that affect the lumbar.3–11 This approach provides anterolateral exposure of the spine from L1 to L5. The following are common indications for use of the flank retroperitoneal approach: Following general anesthetic, the patient is positioned in the lateral decubitus position with the operative side up (typically the left). To prevent iatrogenic injury to pressure points and vulnerable neural structures (brachial plexus, ulnar nerve, and common peroneal nerve), all bony prominence and limbs should be appropriately padded and positioned. The arms should be supported with no greater than 90 degrees of forward flexion and neutral internal and external rotation of shoulders. An axillary role should always be placed. The shoulders and pelvis should be secured perpendicular to the operating room (OR) table (Fig. 38-1). The iliac crest should be left exposed for bone graft harvesting as necessary. The ipsilateral hip should be flexed to relax the psoas muscle. To improve exposure and access, the patient should be positioned with the lumbar spine over the break in the OR table. Flexing the OR table increases the distance between the costal margin and iliac crest and laterally flexes the lumbar spine (Fig. 38-1). Consequently if anterior instrumentation or a strut-graft is being used, the table must be returned to its neutral position prior to placement of the graft or instrumentation. This approach is typically performed from the left side. A left-sided approach is generally preferred for two main reasons. First, mobilization of the aorta is easier compared with the vena cava. Second, the size of the liver and its ligamentous attachments render it relatively immobile compared with the spleen. Hence, a right-sided exposure to the spine provides limited exposure, particularly of the upper lumbar spine (L1 and L2). However, a right-sided approach is indicated if the pathology is predominantly located on the right side. For a full flank approach, an incision is begun from the lateral edge of the posterior paraspinal musculature above, at, or below the level of the 12th rib. For exposure of L1–L2, an incision above T12 and resection of the anterior two thirds of the 12th rib are typically necessary. Complete exposure of L1 can be very difficult and may necessitate takedown of the posterior aspect of the diaphragm, but it is possible with resection of the 12th rib and release of the ipsilateral crus only. The incision is carried to the lateral border of the rectus abdominis at a point midway between the umbilicus and symphysis pubis in an oblique manner (Fig. 38-2). If exposure down to L5 is required, the incision should be curved and extended caudally along the lateral border of the rectus, as necessary. The incision should be tailored to the extent of exposure necessary. For oncologic procedures, where bleeding is often significant and the anatomy is distorted, good exposure should never be compromised by the size of the incision. FIGURE 38-1 (A) An oblique flank incision is made from the posterior half of the 12th rib to the lateral border of rectus abdominis muscle. The posterior aspect of the incision can begin above, at, or below the level of the 12th rib depending on the spinal level of exposure required (L1–L2, L2–L3, L3–L5, respectively). The anterior aspect of the incision is typically at a point halfway between the umbilicus and the symphysis pubis. The incision can be extended distally along the lateral rectus border for greater caudal exposure as required. (B) Flexion of the operating table increases the space between the lower ribs and the ilium to provide improved exposure and access. FIGURE 38-2 The external oblique, internal oblique, and transversus abdominis are divided in line with the incision. Illustrated are the fibers of the internal oblique, which typically run perpendicular to the direction of the incision. The external and internal oblique muscles are individually divided in line with the incision (Fig. 38-2). The transversus abdominis is divided and the transversalis fascia identified. Note the transversalis fascia is very thin and easily entered with division of the transversus abdominis. Anteriorly, below the arcuate (semilunar) line of the rectus (located below the level of the anterior superior iliac spine, ASIS) the transversalis tendon and fascia as well as the peritoneum are intimately related. This anatomic relationship increases the risk of inadvertent entry into the peritoneal cavity; consequently, it is best to enter the retroperitoneal space in the posterior aspect of the exposure. If an inadvertent rent is made in the peritoneum, it should be repaired with a fine absorbable suture. Once the retroperitoneal plane is identified, the peritoneal cavity and its contents can be swept medially and anterior away from the spine using blunt dissection. The ureter is typically located within the retroperitoneal fat and should be identified early in the exposure (Fig. 38-3). Once identified, the ureter should be retracted with the peritoneal cavity and contents. The psoas muscle is easily identified. The genitofemoral nerve (L1, L2), which runs on the ventral surface of the psoas muscle, should be identified and protected throughout the procedure. The sympathetic chain is located on the lateral aspect of the vertebral bodies medial to the psoas muscle. Although the sympathetic chain is frequently sacrificed during anterior spinal procedures, attempts should be made to preserve this structure whenever possible. The aorta and the left iliac artery are identified by their pulsations. The common iliac vessels typically run from medial to lateral across the L4–5 disc space (Fig. 38-4). The descending iliolumbar vein is variable in its location and size. This vein can be easily injured from excessive retraction or blunt dissection. When injured, the iliolumbar vein can result in significant and difficult-to-control blood loss. Consequently this vessel should be carefully identified and ligated early when distal exposure is necessary. FIGURE 38-3 The retroperitoneal space is developed deep to the transversalis fascia. As illustrated, the ureter should be identified. It is typically located within the retroperitoneal fat. If any uncertainty exists, gentle stimulation with a nontoothed forceps creates peristalsis of the ureter to allow definitive identification. The psoas muscle is retracted laterally at the avascular disc spaces to facilitate identification of the segmental vessels. These vessels are located at the midpoint (“valley”) of each vertebral body. Segmental vessel ligation is performed at each vertebra to be included in the spinal procedure. Prior to ligation of the vessels, an intraoperative radiograph should be obtained to confirm the appropriate operative levels. Once the segmental vessels are ligated, the plane between the great vessels and the anterior longitudinal ligament (ALL) is developed by gentle, blunt dissection. In the case of tumors or infection, this plane may be obliterated. In this scenario, this plane should be identified at the normal levels above and below and then developed across the pathologic level. Direct attempts to identify and develop this plane at the pathologic level can lead to catastrophic bleeding. If the surgeon is unable to easily mobilize the great vessels, it is safest to stay posterior to the ALL or intralesional to avoid injury to the great vessels. Once the plane anterior to the ALL is developed, the contralateral aspect of the vertebral body is palpated with a dissecting finger. An appropriately contoured malleable retractor can be placed onto the opposite anterolateral aspect of the vertebral body. This provides excellent spinal exposure and protection of the great vessels (Fig. 38-4). A self-retraining retractor system is essential to maintain static exposure for the remainder of the surgery. The spinal procedure is then performed as required.

Lateral Retroperitoneal Approaches to the Lumbar Spine

Flank Retroperitoneal Approach

Flank Retroperitoneal Approach

Indications

Anterior release

Anterior release

Trauma

Trauma

Tumor (primary and metastatic)

Tumor (primary and metastatic)

Infection

Infection

Interbody fusion

Interbody fusion

Surgical Procedure

Patient Positioning and Approach

Exposure

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree