16 Long Thoracic Nerve Palsy A 23-year-old, right-handed network analyst presented with a protruberant right scapula and difficulty elevating his right arm. These problems had developed 2 days after a strenuous session of upper body weightlifting, and then persisted unchanged for the next 9 months, when he was seen in our clinic. He did not complain of decreased sensation, paresthesia, or dysesthesia in the periscapular area. He did occasionally experience mild right periscapular pain and right-sided neck stiffness, however. His past medical history was unremarkable except for an allergy to acetylsalicylic acid. He took no medications. There was no family history of neurological disorders. On examination, winging of his right scapula was obvious. The scapular winging was made much more prominent when he pushed against the wall with his arm extended at the elbow (Fig. 16–1). He displayed subtle weakness of forward flexion at the shoulder and reduced range of motion with attempted arm elevation. Except for the right serratus anterior muscle, tone, bulk, and power were normal in all other muscles, including the other periscapular muscles. All modalities of sensation were normal throughout the upper extremity. Deep tendon reflexes were symmetrically normal. Two separate electromyographic assessments revealed fibrillations and no recruitable motor unit potentials from the right serratus anterior muscle. Long thoracic nerve palsy Figure 16–1 Classic winging of the right scapula from serratus anterior palsy. The long thoracic nerve is a purely motor nerve that supplies the serratus anterior muscle. It originates from the ventral rami of the C5, C6, and C7 nerve roots. The most frequent pattern is for the long thoracic nerve to arise from the dorsal surface of the distal portion of C6, just before the latter melds into the upper trunk. Although C6 is the major contributor to the long thoracic nerve, branches to this nerve also arise from C5 and C7, and rarely from C8 and C4. Its contributions from C5 and C6 travel through the middle scalene muscle, whereas its C7 element travels anterior to the middle scalene muscle. Eventually these contributions merge into the common nerve, which passes posterior to the first rib and through the axillary apex to the serratus anterior muscle. The nerve has a superficial course over the serratus anterior prior to its insertion into and innervation of the muscle. The most distinguishing clinical characteristic of long thoracic nerve palsy is ipsilateral scapular winging. That is, the medial border and inferior angle of the scapula are posterolaterally displaced. In addition to classic winging of the scapula, shoulder pain and decreased range of motion can also occur with long thoracic neuropathy. Although the long thoracic nerve contains no sensory fibers, pain can result from compensatory overuse and subsequent strain of other periscapular muscles. If the patient displays a sensory deficit, however, other or additional pathologies must be involved. Weakness is most prominent in forward flexion at the shoulder, with the elbow fully extended. Moreover, because the serratus anterior muscle can no longer stabilize the scapula when the long thoracic nerve is injured, the glenoid fossa blocks the arm from abducting past the horizontal plane (Table 16–1). Injury to the long thoracic nerve is often due to blunt trauma to the thorax or sudden depression of the shoulder. This can occur during a fall or collision. This type of injury has been reported in association with participation in almost every sport. Overuse of the shoulder and strenuous exercise have also been implicated. Penetrating trauma is another cause of injury to the long thoracic nerve. Electrical injury to the long thoracic nerve may also lead to winging of the scapula. Iatrogenic injury to the nerve during surgical procedures, such as radical mastectomy, first rib resection, and transaxillary sympathectomy is well described. Identification and avoidance of the long thoracic nerve when operating in its vicinity is therefore very important. Prolonged arm abduction and external rotation are other potential causes of long thoracic neuropathy seen after improper positioning in the operating room or prolonged bed rest. Viral illnesses, Parsonage-Turner syndrome, and isolated long thoracic neuritis have also been implicated in serratus anterior palsy. Parsonage-Turner syndrome should strongle be considered when onset of pain precedes weakness in patients. In many patients, no cause for serratus anterior palsy can be identified (idiopathic).

Case Presentation

Case Presentation

Diagnosis

Diagnosis

Anatomy

Anatomy

Characteristic Clinical Presentation

Characteristic Clinical Presentation

| Scapular winging |

| Posterior shoulder pain |

| Weakness of shoulder flexion |

| Decreased range of motion at the shoulder |

Differential Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

Several conditions must be considered in the differential diagnosis of long thoracic neuropathy. Rotator cuff tear, glenohumeral and acromioclavicular joint disease, biceps tendonitis, scoliosis, other brachial plexus injuries, and scapular osteochondroma can all result in shoulder dysfunction and pain.

Special consideration is required in the patient with scapular winging, which can occur with accessory and dorsal scapular palsies, in addition to long thoracic nerve palsy. Paralysis of the serratus anterior gives severe winging of the scapula, both at rest and with the shoulder flexed and the elbow fully extended. This differentiates it from the winging associated with trapezius paralysis (from accessory neuropathy), in which winging is maximal with shoulder abduction and minimal when the elbow is fully extended and the hand and arm push forward against resistance. Paralysis of rhomboid muscles (from dorsal scapular nerve palsy) can be observed as an absence of bulk medial to the scapula, most noticeable when the subject braces the shoulders as if at military attention. Loss produces some winging, lateral and slight downward displacement of the scapula, and a slightly awkward abduction of the shoulder. This abduction difficulty is, however, not as profound as that seen with serratus anterior or trapezius paralysis.

Diagnostic Tests

Diagnostic Tests

Plain radiographs of the cervical spine, shoulder, and thorax can be helpful to identify cervical spine disease, or mass lesions such as osteochondroma of the scapula that might account for scapular winging. Further imaging with computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging might then be relevant, depending on the radiographic findings and suspected etiology of the condition. Imaging, however, is usually normal. Electromyography is important in the workup of patients with suspected long thoracic neuropathy, showing denervational changes in the muscle along with a loss of motor unit action potentials. Initially, electromyographic assessment of the other periscapular muscles is important because concomitant weakness in these muscles may affect surgical outcome and therefore influence management decisions. Electrodiagnostic tests of the serratus anterior muscle can then be repeated on a serial basis to assess recovery or deterioration.

| Failed nonoperative management |

| Penetrating trauma or iatrogenic nerve transection |

Management Options

Management Options

Nonoperative and surgical management techniques are employed in the treatment of long thoracic neuropathy. One important nonoperative approach is the use of range of motion exercises. These are instituted to maintain full mobility at the shoulder. Light resistance exercises to strengthen the other shoulder girdle muscles are also used. Symptomatic relief of pain can often be achieved with mild analgesics and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Some authors have also described the use of braces and orthotics to aid in the stabilization of the scapula against the thoracic cage, but it is not clear that these devices contribute to functional improvement or overall recovery. Moreover, because these devices can promote immobility, they may actually hinder functional recovery.

For those patients who, despite a reasonable trial of conservative management, find their persistent signs and symptoms to be unmanageable or debilitating, surgical intervention should be considered (Table 16–2). Early surgical treatment may be appropriate for those whose condition is clearly related to a partial or complete transection injury to the long thoracic nerve.

Surgical Treatment

Surgical Treatment

There are four categories of surgical treatment for long thoracic neuropathy: scapulothoracic fusion; static stabilization procedures; direct nerve repair, grafting, or neurolysis; and dynamic muscle transfers.

Scapulothoracic fusion produces an undesirable elimination of all scapulothoracic movement in addition to the elimination of scapular winging. For this reason, it is generally reserved as a secondary option once other techniques have been attempted and failed, or when involvement of other periscapular muscles has already impaired normal scapulothoracic movement.

Static stabilization procedures involve tethering the scapula to the ribs or vertebral spinous processes using a fascial graft or sling. Because of the tendency of these grafts and slings to stretch out and lose effectiveness over time, they are not generally used alone.

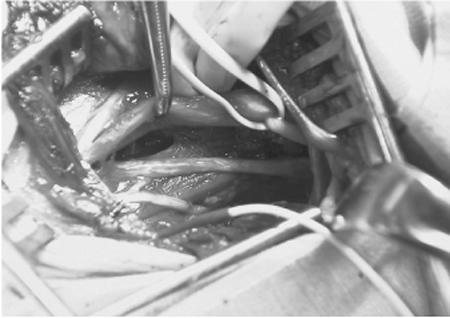

As in other nerve injuries, complete transections of the long thoracic nerve may be repaired primarily or with the aid of nerve grafts. The nerve damage may be compressive in nature. A typical location for this compression is within and around the middle scalene muscle. Decompressive neurolysis is a controversial management option in such cases. It involves freeing the nerve in and around the scalene muscles (Fig. 16–2).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree