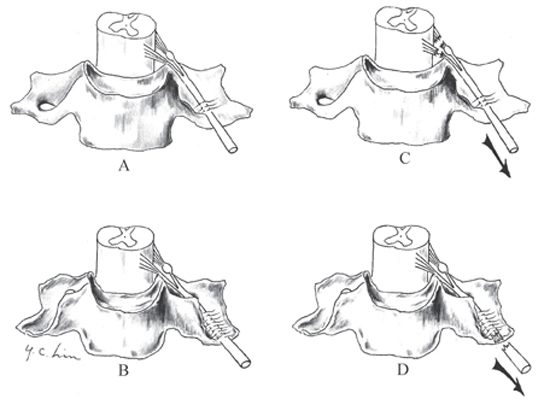

3 Lower Trunk Brachial Plexus Palsy A 26-year-old male, in his usual state of good health, suffered a motorcycle accident. As his motorcycle skidded, he retained his grasp on the handlebars as the motorcycle spun away from him. His right arm was abducted at the shoulder and extended at the elbow, and he sustained a significant road rash to the right side of his chest and medial aspect of his arm and elbow. Examination at the time of the initial presentation revealed significant weakness in the intrinsic muscles of his right hand and numbness along the medial aspect of his arm and hand. Inspection revealed ptosis of the right eye and miosis. No other neurological or vascular deficits were present. Radiographic studies of the cervical spine, chest, and arm in the emergency room revealed fractures of the clavicle and first rib. Figure 3-1 Lower trunk spinal nerves are prone to preganglionic injury. (A) The bony “chutes” of the lower trunk spinal nerves are abbreviated when compared with (B) those transmitting the upper trunk spinal nerves, and the lower trunk spinal nerves traversing these bony “chutes” are less bound to the bone by connective tissue. (C) Consequently, the C8 and T1 nerves are prone to preganglionic injury, whereas (D) the nerves of the upper trunk tend toward postganglionic injury. Lower trunk brachial plexus palsy The lower trunk of the brachial plexus is formed by the C8 and T1 spinal nerves. These nerves exit from their neural foramina and run along the bony groove between the anterior and posterior tubercles of the vertebrae (Fig. 3–1). These bony “chutes” are abbreviated (Fig. 3–1A) when compared with those transmitting the nerves for the upper trunk of the brachial plexus (Fig. 3–1B), and the lower trunk spinal nerves traversing these bony “chutes” are less bound to the bone by connective tissue. Consequently, the C8 and T1 spinal nerves are prone to preganglionic injury (Fig. 3–1C), whereas the nerves comprising the upper trunk tend toward postganglionic injury (Fig. 3–1D). The C8 and T1 spinal nerves merge to form the lower trunk, and along with the upper and middle trunks, the lower trunk of the brachial plexus emerges from the posterior triangle of the neck between the anterior and middle scalene muscles. The T1 spinal nerve usually lies in front of the C8 spinal nerve (rather than side-to-side), and the subclavian artery passes anteromedially to them on the first rib. The lower trunk divides into the anterior and posterior divisions. The posterior division merges with the posterior divisions of the upper and middle trunk to form the posterior cord, whereas the anterior division continues distally to form the medial cord. Branches from the medial cord supply (1) motor function to the pectoralis minor and the sternal head of the pectoralis major (medial pectoral nerve) and (2) sensory function to the medial aspect of (a) the arm (medial cutaneous nerve) and (b) the forearm (medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve). After giving off these branches, the medial cord divides to give contributions to the median and ulnar nerves. These contributions derived from the C8 and T1 spinal nerves, carried by the median and ulnar nerves, supply all of the intrinsic muscles of the hand, innervated by both the median and ulnar nerves, and sensory fibers to the ulnar nerve territory of the hand. Near the C7 and T1 transverse processes lies the stellate ganglion. In ˜80% of the population, the inferior cervical ganglion and the first thoracic ganglion fuse to form the stellate ganglion. This structure (and/or these ganglia) carry all the sympathetic flow to the head and neck structures either by providing a location for synapse of the pre- to postganglionic axons or by allowing the passage of sympathetic fibers to the more cephalic sympathetic ganglia. Disruption of the stellate ganglion results in lack of sympathetic input to the head and neck, resulting in Horner syndrome. The hallmark of lower plexus injury in the supraclavicular region is hand weakness, usually accompanied by Horner syndrome (ptosis, miosis, and anhydrosis). Sensory deficit is present along the medial aspect of the arm, forearm, and hand. The mechanism of injury is generally traction of the arm while the shoulder is abducted and the elbow extended. Isolated lower trunk palsies are rare, representing ˜5% of brachial plexus injuries, and lower trunk palsies are more often seen as a component of severe panbrachial plexus injuries. Supraclavicular injuries are more common than infra-clavicular injuries to the brachial plexus. Trauma to the supraclavicular brachial plexus can be associated with injury to other vital structures due to their proximity. Injury of the subclavian artery occurs in ˜15% of cases, and concurrent spinal cord injury occurs in ˜5% of cases. Nerve injury, such as that to the brachial plexus, can be classified according to Seddon: neurapraxia, axonotmesis, and neurotmesis. The majority of lesions tend toward neurapraxic or axonotmetic injuries and can recover spontaneously. In ˜20% of cases, neurotmetic lesions such as preganglionic injury to the lower nerves of the brachial plexus occur. These injuries never recover spontaneously and usually require aggressive intervention. Besides traumatic/traction disruption of the brachial plexus, other causes of injury to the lower trunk include contusion (e.g., gunshot wound), compression (e.g., bony overgrowth, thoracic outlet syndrome), laceration/disruption (e.g., trauma, iatrogenic), and ischemia. Eliciting the mechanism and severity of the injuring circumstances can help in the initial assessment as well as in assessing the potential for recovery. Understanding the clinical presentation of lower brachial plexus palsy (with its potential accompanying vascular or autonomic symptoms and signs) relies upon understanding the anatomy of the lowermost nerves of the brachial plexus and their surrounding structures. The physical findings in these lower plexus palsies reflect the contributions of the C8 and T1 spinal nerves. There is loss of function of all the intrinsic hand muscles innervated by both the median and the ulnar nerves. This is best demonstrated by testing the abductor pollicis brevis or the opponens pollicis (median nerve) and the abductor digiti minimi, first dorsal interosseous, and adductor pollicis for the ulnar nerve. Sensory loss is confined to the ulnar nerve distribution. Median nerve sensation is preserved because its sensory supply is from the upper and middle trunks. This combined motor loss with median nerve sensory preservation is the hallmark of lower trunk palsy. Horner syndrome is present, especially if there is avulsion of the C8 and T1 spinal nerves. The history and physical findings just described point to a lesion of the lowermost spinal nerves or trunk of the supraclavicular brachial plexus. An injury more distal such as to the medial cord would not result in sensory deficits of the medial upper arm and forearm nor would this injury be associated with Horner syndrome. The presence of a Horner pupil strongly suggests nerve avulsions of C8 and T1. Injury of the ulnar nerve would not result in paresis of the median nerve–innervated hand intrinsic muscles or sensory loss in the arm or forearm. These studies can be classified as electrophysiology and imaging. Electrophysiological studies include electromyography (EMG) and nerve conduction studies (NCS). These studies are usually performed 3 to 4 weeks after injury. Regarding the type of neuronal injury, the lack of denervational changes (e.g., fibrillation) with EMG implies the presence of neurapraxic injury, whereas the presence of persistent denervational changes implies axonotmetic or neurotmetic injury. The appearance of late-appearing (weeks to months) reinnervation motor unit potentials (MUPs) distinguishes between axonotmetic and neurotmetic injury. Regarding localization of the lesion, EMG examination that reveals abnormal findings in the paraspinal muscles places the lesion at the level of the spinal nerve roots. The persistence of normal sensory nerve action potentials (SNAPs) corresponding to completely anesthetic regions is consistent with a preganglionic lesion (e.g., avulsion) because the cell bodies lie in the dorsal root ganglion and the sensory axons are preserved; a postganglionic lesion would result in degeneration of the distal sensory fibers that were severed from their cell body in the dorsal root ganglion and lack of a SNAP. Intact somatosensory-evoked potentials (SEPs) and motor-evoked potentials (MEPs) imply continuity between the spinal cord and the spinal nerve root, helping rule out a preganglionic lesion. Imaging studies include plain radiography, computed tomography (CT), myelography, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Plain radiographs remain useful for assessing the severity of the injury: fracture of the cervical vertebrae or adjacent bony structures (especially the first rib) implies a severe mechanism of injury. Tilting of the cervical spine away from the site of injury may be seen with avulsion injury. The presence of an elevated hemidiaphragm on chest x-ray implies injury at the level of the nerve roots: the phrenic nerve is formed from C3, C4, and C5 adjacent to the neural foramina. CT myelography revealing pseudomeningoceles strongly suggests avulsion injury. In addition, MRI abnormalities (e.g., edema, hemorrhage) in the spinal cord or the displacement of the spinal cord or both are consistent with avulsion injury of the spinal nerves. The correlation of the electrophysiological studies with the imaging studies in addition to information gleaned from a careful history and physical examination can aid in determining the site of the lesion and its severity. The first step in the management of brachial plexus injuries is to determine whether there is an associated vascular injury. In the absence of a radial pulse, angiography and treatment of the vascular injury are foremost. In this context, the symptoms and signs of nerve injury should be most severe at the time of the injury: progressive neurological deficits imply worsening nerve compression (e.g., from a hematoma), and occult vascular injury should be suspected. The indications for immediate exploration are essentially related to the presence of vascular injury or the presence of “clean” lacerations. If the nerves are sharply divided, they are repaired; if the ruptured nerve endings are considered “untidy,” they are tagged for future repair. Closed traction injuries of the brachial plexus should be initially managed conservatively because many closed traction injuries recover spontaneously. Serial examinations and electrophysiological studies can distinguish between “recovering” and “nonrecovering” lesions. Imaging studies can aid in preoperative planning, and exploration or repair of the “nonrecovering” lesion is usually performed ˜6 months postinjury. The lower plexus elements described are nearly always injured by traction mechanisms. Open injuries such as lacerations or missile wounds are extremely rare. Even the compression injury to the lower trunk seen in some instances of thoracic outlet syndrome is very uncommon, occurring in about one in 1 million people. Virtually all lower trunk traction injuries are nerve (root) avulsions. These injuries cannot be directly repaired, although experimental work continues in this field. Nerve grafts and nerve transfers have been used to try to recover sensory function in the hand with widely variable results. A few reports suggest that some finger grasp function can be restored with heroic nerve grafts and transfer procedures, especially in the context of free muscle transfers. Outcomes in obstetric cases and children seem to be better than those in adults. Currently, there is little hope of spontaneous recovery or assisted recovery of intrinsic hand motor function. The outcome and prognosis for this injury, isolated or as a part of a severe total plexus injury, therefore remains relatively grim.

Case Presentation

Case Presentation

Diagnosis

Diagnosis

Anatomy

Anatomy

Characteristic Clinical Presentation

Characteristic Clinical Presentation

Differential Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

Diagnostic Tests

Diagnostic Tests

Management Options

Management Options

Outcome and Prognosis

Outcome and Prognosis

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree