Chapter 219 Management of a Patient with Thoracolumbar Fracture with Complete Myelopathy and a 40-Degree Kyphotic Deformity

Operative or Recumbent Management

Operative Management

The 40-degree kyphotic deformity in a patient with a thoracolumbar fracture with complete myelopathy suggests that this patient has sustained a flexion-compression injury with wedging of the vertebral body. Because myelopathy is complete, decompression is not likely to improve the patient’s neurologic status.1 However, there is a very small possibility of recovery, which I believe supports strong consideration of decompression. Continued compression also may delay syringomyelia and/or pain following injury, again arguing for decompression and stabilization.

Because stabilization is the main goal of treatment, either a ventral or dorsal approach would be appropriate. Corpectomy and instrumentation may be performed, or a dorsal long- or short-segment pedicle screw construct may be used. The decision often is made based on the need for ventral column support. If there is substantial comminution of the vertebral body, significant spacing between the fragments, or inability to correct the kyphosis adequately, ventral column reconstruction or long-segment dorsal instrumentation will be required.2 If surgery is chosen, correction of deformity should be attempted. This may be accomplished either ventrally or dorsally. In my experience, there is minor loss of correction following either ventral or dorsal reconstruction. No correlation has yet been demonstrated between residual kyphosis and clinical outcome, including pain following treatment (including nonoperative management).3

Bracken M.B., Shepard M.J., Collins W.F.Jr., et al. Methylprednisolone or naloxone treatment after acute spinal cord injury: 1-year follow-up data. Results of the second National Acute Spinal Cord Injury Study. J Neurosurg. 1992;76(1):23-31.

Brown C.W., Gorup J.M., Chow G.H. Nonsurgical treatment of thoracic burst fractures. In: Zdeblick T.A., Benzel E.C., Anderson P.A., Stillerman C.B., editors. Controversies in spine surgery. St. Louis: Quality Medical; 1999:86-96.

Frankel H.L., Hancock D.O., Hyslop G., et al. The value of postural reduction in the initial management of closed injuries of the spine with paraplegia. Part I. Paraplegia. 1969;7:179-192.

Thomas K.C., Bailey C.S., Dvorak M.F., et al. Comparison of operative and nonoperative treatment for thoracolumbar burst fractures in patients without neurological deficit: a systematic review. J Neurosurg Spine. 2006;4(5):351-358.

1. Bracken M.B., Shepard M.J., Collins W.F.Jr., et al. Methylprednisolone or naloxone treatment after acute spinal cord injury: 1-year follow-up data. Results of the second National Acute Spinal Cord Injury Study. J Neurosurg. 1992;76(1):23-31.

2. Brown C.W., Gorup J.M., Chow G.H. Nonsurgical treatment of thoracic burst fractures. In: Zdeblick T.A., Benzel E.C., Anderson P.A., Stillerman C.B., editors. Controversies in spine surgery. St. Louis: Quality Medical; 1999:86-96.

3. Patel A.A., Dailey A., Brodke D.S., et al. Thoracolumbar spine trauma classification: the Thoracolumbar Injury Classification and Severity Score system and case examples. J Neurosurg Spine. 2009;10(3):201-206.

Recumbent Management

An acute fracture of the lower half of the thoracic spine or lumbar spine with an angulation of 40 degrees and a complete myelopathy is inherently unstable. Such an angular deformity with compromise of the spinal canal is associated with fracture of the vertebral body, and, more than likely, disruption of the posterior ligaments. Based on biomechanical and clinical data, criteria for instability in this case are satisfied.1–3 The medical condition of the patient permitting, appropriate management acutely will most likely consist of decompression, correction of deformity, and stabilization. Indeed, recently a large number of spinal implants advocated for the achievement of immediate stability have become available. The intent of such an approach has been early mobilization of the patient, a shorter hospital stay, and the achievement of neural decompression, reduction, and stabilization. These goals, however, have not always been achieved, rekindling an interest in nonoperative recumbent treatment. Such nonoperative management of thoracolumbar fractures is by no means novel. It initially was advocated in the 1940s with Guttman4 at the Stoke Mandeville Hospital (Aylesbury, UK) and Nicoll5 at the Mansfield General Hospital (Mansfield, UK). This tradition was continued by Frankel et al.6 and Bedbrook and Ohn7 in patients with paralysis. In recent years, nonoperative treatment of intact thoracolumbar fractures has been adopted, and has been found to provide excellent results.8–13

In thoracolumbar fractures with partial deficit, neurologic improvement has been demonstrated with both treatment modalities.14–17 No consistent improvement has been reported in complete spinal cord injury with either surgical or recumbency treatment. Angulation has been shown to be more effectively corrected with operative than with nonoperative treatment.14–1618 Nevertheless, deformity progresses with the passage of time, irrespective of treatment. It has been shown that angulation exceeding 30 degrees is associated with a moderate to severe degree of pain.14 However, historically, gibbus deformities of up to 40 degrees did not prohibit patients from achieving, in some cases, satisfactory outcomes and gainful employment in the coal mines.5

Early surgical intervention for the management of thoracic and lumbar fractures usually has been advocated to provide for a shorter hospital stay, allowing for early rehabilitation. The difference in length of hospital stay between operative and nonoperative treatment in spinal fractures has not always been significant.15,17 However, these studies were not randomized and are dated, and patients were not matched in deficit. In this age of skyrocketing medical costs, the cost of surgical intervention, including operating room fees, anesthesia, expendables, implants, and surgeon’s fees, are by no means insignificant.12,15 In fact, a comparative analysis of hospital costs was conducted between operative and nonoperative treatment in thoracolumbar burst fractures. Total hospital charges of patients undergoing surgery were 2 to 4 times the charges of equivalent patients treated nonoperatively.12,15 Patients with thoracolumbar fractures treated with either operative or nonoperative means have returned to their previous employment. Unfortunately, these groups have not been matched appropriately for deficit prior to treatment, and thus comparison is not always meaningful.15,16

Complications arising from surgical intervention include infection, hardware failure, subsequent surgery, and deep vein thrombosis. These, in general, have exceeded those encountered in recumbency.12,14,15,17–19 This has led to the adoption of recumbency in patients who are intact, or those with a total lesion of the spinal cord in whom the chances of improvement are nil.

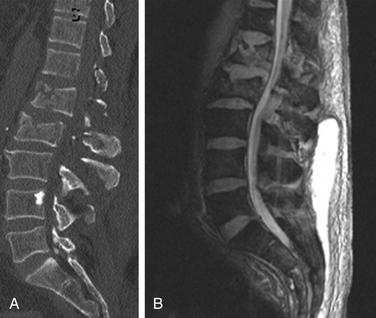

In a patient with a complete lesion secondary to a thoracolumbar fracture associated with a 40-degree kyphotic deformity, surgical intervention may be contraindicated. These patients may have visceral injuries, pulmonary contusions, hemopneumothorax, and respiratory insufficiency. In addition to head injury, these patients may require prolonged ventilatory support. Their stay in the intensive care unit may be further complicated by pneumonia, sepsis, and, in many cases, posttraumatic pancreatitis. These conditions militate against surgical intervention of any type, let alone a lengthy procedure of spinal stabilization with the potential for significant blood loss. Under those circumstances, recumbency may be the only treatment that can be offered to such patients. After 1 to 6 weeks of bedrest, depending on the nature of the fracture, patients can then be mobilized gradually in a customized plastic thoracolumbar orthosis. Radiographs usually are obtained sequentially at 45 and 90 degrees to confirm stability and the absence of progressive kyphosis. In the absence of instability, rehabilitation can proceed rapidly thereafter. The clamshell thoracolumbar orthosis is worn for a total of 3 months whenever the patient is sitting up. Upright radiographs usually are obtained at 3, 6, and 12 months. In the presence of increasing pain, or deterioration in neurologic condition, surgery may be undertaken, as was the case in the patient shown in Figure 219-1.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree