Mechanisms of Epileptogenesis and Experimental Models of Seizures

Imad Najm

Gabriel Möddel

Damir Janigro

The term epileptogenesis refers to abnormal firing of neurons sufficient to produce episodic epileptiform electrophysiologic activity that is detected as electroencephalographic (EEG) seizure activity with or without clinical manifestations. Such electric discharges may start in small neuronal populations (focal epilepsy), or in the entire brain simultaneously (generalized epilepsy). These epilepsies may be congenital or acquired.

The availability of resected focal epileptic tissue from patients with medically intractable focal epilepsy and the development and characterization of animal models for various types of epilepsies have enabled a better understanding of some of the cellular and electrophysiologic mechanisms of epileptogenesis. At the single cell or local circuitry levels, in vitro models of hyperexcitability/synchronization have provided additional insight into the various mechanisms of epileptogenicity.

Multiple factors contribute to the expression of epileptogenesis, such as intracellular, intrinsic membrane, and extracellular mechanisms. Based on animal data, Prince and Connors (1) hypothesized that three key elements contribute to the hyperexcitability needed for the expression of epileptogenesis: (a) the capability of membranes in pacemaker neurons to develop intrinsic burst discharges; (b) reduction of γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) inhibition; and (c) enhancement of synaptic excitation through recurrent excitatory circuits (e.g., mossy fiber sprouting in hippocampal sclerosis). Although intrinsic membrane hyperexcitability provides a substrate for epileptogenesis, circuit dynamics are more important for the expression of paroxysmal electrophysiologic tendencies. Multicellular synchronization is necessary for the EEG and behavioral seizure expression, and is critical for the expression of interictal and ictal activities, as well as for the generation of cellular paroxysmal depolarization shifts. Whereas hyperexcitability may be easily reconciled with changes in neuronal circuitry, synchronization may involve other cell types (e.g., glia) and changes in the composition and size of the extracellular space.

This chapter reviews recent findings on the cellular mechanisms of hyperexcitability and data on the mechanisms of hypersynchrony in patients with focal epilepsies. A brief review of some animal models of epilepsies and their relevance and contribution to the investigation of epileptogenicity is presented at the end of the chapter.

HYPEREXCITABILITY

Two complementary mechanisms determine neuronal excitability: intrinsic membrane properties of neurons and ratio of inhibitory versus excitatory synapses (2). Consequently, extracellular levels of membrane-permeant ions and molecules available for neurotransmission also play a role. The control of neuronal excitability thus depends on numerous factors, including gating properties and voltage-dependency of ion channels, density of functional synapses, concentrations of ions, and availability of

mechanisms to clear ions and neurotransmitters from the extracellular space. Neuronal cells use a single type of signaling based on all-or-nothing action potentials. Sodium action potentials, such as those recorded in axons or cell bodies, are relatively invariant in normal tissue, and thus the shape and duration of these electrical signals do not vary significantly within the nervous system. Calcium action potentials are similarly predictable, but the underlying ionic mechanism can be rather complex, depending on the cell type, and on the topographic location within the cell. The terms sodium action potential and calcium action potential refer only to the initial (depolarizing) phase of these rapid membrane polarity changes. Although genetic or molecular alteration of INa and ICa can significantly affect neuronal firing and, ultimately, the neurophysiology of a given region, gross changes in neuronal excitability may also result by alteration of the repolarization phase of individual action potentials. Given these considerations, it is not surprising that agents that prolong action potential duration (typically, potassium-channel blockers such as tetraethylammonium or tetraethyl barium) are proepileptogenic, while blockers of INa and ICa are used in the pharmacotherapy of epilepsy (e.g., phenytoin, valproic acid, and ethosuximide).

mechanisms to clear ions and neurotransmitters from the extracellular space. Neuronal cells use a single type of signaling based on all-or-nothing action potentials. Sodium action potentials, such as those recorded in axons or cell bodies, are relatively invariant in normal tissue, and thus the shape and duration of these electrical signals do not vary significantly within the nervous system. Calcium action potentials are similarly predictable, but the underlying ionic mechanism can be rather complex, depending on the cell type, and on the topographic location within the cell. The terms sodium action potential and calcium action potential refer only to the initial (depolarizing) phase of these rapid membrane polarity changes. Although genetic or molecular alteration of INa and ICa can significantly affect neuronal firing and, ultimately, the neurophysiology of a given region, gross changes in neuronal excitability may also result by alteration of the repolarization phase of individual action potentials. Given these considerations, it is not surprising that agents that prolong action potential duration (typically, potassium-channel blockers such as tetraethylammonium or tetraethyl barium) are proepileptogenic, while blockers of INa and ICa are used in the pharmacotherapy of epilepsy (e.g., phenytoin, valproic acid, and ethosuximide).

The mechanisms of epilepsy and of normal brain function are interlinked. Seizures result from excessive excitation or, in the case of absence seizures, from disordered inhibition. We summarize here some of the synaptic adjustments that may underlie these proepileptogenic changes in focal epilepsies.

AMPA and NMDA Glutamate Receptors

Glutamate is an amino acid neurotransmitter that mediates synaptic excitation in a large number of synapses in the central nervous system (CNS). The postsynaptic excitation induced by glutamate release depends largely on the specific receptor stimulated, but the overall effect on population behavior depends on the cellular target of excitatory input (i.e., principal vs. interneurons). On the basis of their pharmacologic and physiologic properties, the neuronal glutamate receptors are organized into two classes: ionotropic and metabotropic. The ionotropic receptors can be divided into two subpopulations, those that respond to α-amino-3-hydroxyl-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) and/or kainic acid (KA) and those that respond to N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) (3,4). Excitatory transmission appears to involve actions mediated by one or more combinations of these receptors. AMPA receptor channels are responsible for fast excitatory neurotransmission by the sodium-potassium channel and coexist with NMDA receptors in all synapses (3). NMDA receptor channels display slow opening and closing kinetics, and are permeated to both sodium and calcium. At normal resting membrane potential, the channel pore is obstructed by a magnesium ion (“magnesium block”). Depolarization of the postsynaptic membrane (e.g., by activation of AMPA receptors and subsequent sodium influx) releases the magnesium block, and NMDA channels open to Na+ and Ca2+ entry and provide the prolonged phase of the excitatory neurotransmission (5,6).

In 1973, Bliss and Lomo (7) demonstrated that relatively brief (millisecond) bursts of high-frequency stimulation induced long-lasting changes—enhancement, hence the term long-term potentiation (LTP)—of postsynaptic responses in the hippocampus. Owing to the enduring nature of this response and the relatively physiologic nature of the stimuli used, it has been suggested that LTP may constitute the synaptic mechanism of learning and memory. More recently, the flip side of LTP [i.e., long-term depression (LTD)] has been described, whereby synapses are “depotentiated” or partially silenced when long-lasting (minutes), low-frequency (1 Hz) stimuli are applied. Again, the original discovery of LTD was made in the hippocampal slice preparation, but LTP and LTD have been described in a variety of CNS synapses.

Both LTP and LTD share common features and can be elicited at the same synapse. Two forms of LTP have been described in the hippocampus (8). First, a Hebbian postsynaptic NMDA receptor-dependent form is seen in the CA1 region at the Schaffer collaterals-commissural axons and CA1 pyramidal cells; to trigger this form of LTP, several concomitant factors must be present. In addition, depending on the magnitude of these factors, either LTP or LTD occurs. The whole process is initiated by increases in presynaptic calcium concentration, triggered by presynaptic excitation; release of transmitter (glutamate) ensues, and activation of postsynaptic receptors initiates changes in the target cell. The magnitude of postsynaptic changes in intracellular calcium will determine whether LTP or LTD will be induced. Of relevance activation of postsynaptic, calciumpermeant NMDA receptors is essential for either process. As the NMDA receptor channel is voltage-dependently blocked by extracellular magnesium ions, one of the essential steps in this process involves removal of Mg2+ blockade (6). Physiologically, this occurs with depolarization of the postsynaptic membrane. Under experimental conditions, this can also be achieved by alteration of extracellular ion concentrations (i.e., removal of magnesium from the bathing medium). Hence (a) quasi-simultaneous depolarization by post- and presynaptic terminals is required for induction and maintenance of this form of synaptic plasticity, and (b) the resulting form of plasticity (LTP or LTD) depends on changes in [Ca2+]in.

The second form of hippocampal LTP is found at the mossy fiber (axon terminal of the dentate gyrus pyramidal cells)-CA3 pyramidal cell synapses. In contrast to its CA1 counterpart, this form of synaptic plasticity does not require postsynaptic depolarization, activation of NMDA receptors, or postsynaptic changes in [Ca2+]in, but depends rather on changes in presynaptic terminals. In spite of the numerous studies of LTP and LTD in preparations as diverse as isolated cells, cultured brain slices, and acutely

isolated brain slices, and biochemical/molecular studies of subcellular fragments, a compelling demonstration of the physiologic relevance of LTP or LTD is still lacking. In particular, and relevant to the neurologic-neurosurgical practitioner, it is not clear whether loss of these forms of synaptic plasticity affects cognitive brain function or formationretention of memory. Supporting a physiologic role for LTP are studies demonstrating that posttraumatic changes in cognitive function are paralleled by loss of measurable hippocampal LTP (9,10). Interestingly, whereas LTP was affected both in vivo and in vitro, LTD was spared and could be elicited in the same cells in which LTP was lacking (9), suggesting that the underlying pathologic changes did not imply cell loss or gross impairment of synaptic transmission. A possible mechanism of selective loss of LTP may depend on the facts that induction of LTP is a saturable phenomenon and that only a certain level of potentiation can be achieved at any given synapse. It was proposed that trauma may produce a nonspecific potentiation of synapses, impeding further LTP induced by physiologic stimuli. How traumatic brain injury may potentiate synaptic transmission remains unclear, but it is possible that changes in extracellular potassium, such as those seen after traumatic brain injury (9,11), may cause sufficient depolarization of pre- and postsynaptic terminals leading to [Ca2+]in rises comparable to those normally achieved by physiologic action potential progression through presynaptic axons. Given the consideration listed above, this hypothesis predicts that the non-Hebbian form of LTP at the mossy fiber-CA3 interface should not be affected. Because several aspects of LTP-LTD partially overlap those believed to be involved in epileptogenesis (role of NMDA receptors; synaptic rearrangement; role of [K+]out; posttraumatic changes in excitability; similarities between kindling and LTP), it is possible that excessive LTP (or LTD?) may play a role in seizure disorders.

isolated brain slices, and biochemical/molecular studies of subcellular fragments, a compelling demonstration of the physiologic relevance of LTP or LTD is still lacking. In particular, and relevant to the neurologic-neurosurgical practitioner, it is not clear whether loss of these forms of synaptic plasticity affects cognitive brain function or formationretention of memory. Supporting a physiologic role for LTP are studies demonstrating that posttraumatic changes in cognitive function are paralleled by loss of measurable hippocampal LTP (9,10). Interestingly, whereas LTP was affected both in vivo and in vitro, LTD was spared and could be elicited in the same cells in which LTP was lacking (9), suggesting that the underlying pathologic changes did not imply cell loss or gross impairment of synaptic transmission. A possible mechanism of selective loss of LTP may depend on the facts that induction of LTP is a saturable phenomenon and that only a certain level of potentiation can be achieved at any given synapse. It was proposed that trauma may produce a nonspecific potentiation of synapses, impeding further LTP induced by physiologic stimuli. How traumatic brain injury may potentiate synaptic transmission remains unclear, but it is possible that changes in extracellular potassium, such as those seen after traumatic brain injury (9,11), may cause sufficient depolarization of pre- and postsynaptic terminals leading to [Ca2+]in rises comparable to those normally achieved by physiologic action potential progression through presynaptic axons. Given the consideration listed above, this hypothesis predicts that the non-Hebbian form of LTP at the mossy fiber-CA3 interface should not be affected. Because several aspects of LTP-LTD partially overlap those believed to be involved in epileptogenesis (role of NMDA receptors; synaptic rearrangement; role of [K+]out; posttraumatic changes in excitability; similarities between kindling and LTP), it is possible that excessive LTP (or LTD?) may play a role in seizure disorders.

NMDA receptors are unique among glutamate receptors because of their voltage dependence and high permeability to Ca2+. Molecular studies show that the NMDA receptor is composed of subunits from two gene families designated NR1 and NR2 (12, 13, 14, 15). There are four NR2 gene products (NR2A-D) and a single NR1 gene product that can be expressed in eight different splice variants, which arise from different combinations of a single 5-prime terminal exon insertion or two 3-prime exons deletion (13,16). The NR1 subunits form a functional multimeric channel and show all the characteristic properties of an NMDA receptor (14). In contrast to NR1, members of the NR2 family expressed by themselves, or in combination with other NR2 members, never yield functional channels. However, the combined expression of individual NR2 subunits with NR1 markedly potentiates channel opening and current responses to NMDA or glutamate (14). All of these in vitro studies suggest that, at individual NMDA receptor channels, NR1 subunits serve as the general component of NMDA receptors and are essential for receptor function and that NR2 subunits potentiate the channel activities to yield an increased ionic current.

Owing to the powerful influence of glutamatergic neurotransmission and the quasi-ubiquitous expression of glutamate receptors in the mammalian brain, it has been proposed that glutamatergic neurotransmission may play an important role in the pathogenesis of a variety of CNS disorders such as ischemic insults, neurodegenerative diseases, and epilepsy (17, 18, 19, 20). Because acute activation of NMDA receptors plays a role in the neuronal cell loss seen in some forms of focal epilepsy (e.g., mesial temporal lobe epilepsy as a result of hippocampal sclerosis), what could be the link between epileptogenesis and glutamate receptors?

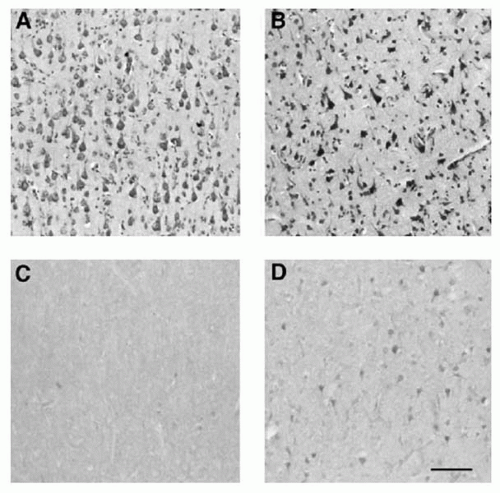

The cellular mechanisms underlying epileptogenicity in cortical dysplasia, particularly the role of AMPA/NMDA receptors in seizure expression, was investigated in dysplastic cortex resected from patients suffering from medically intractable epilepsy. A correlation was found between cytoarchitectural abnormalities and specific NMDA (NR1 and NR2A/B) and AMPA (GluR2-3) receptor subunits (21). These studies offered indirect evidence of a differential expression of some NMDA/AMPA receptor subunits in

dysplastic neurons. The degree of NR1 and NR2A/B receptor expression in focal epileptogenicity has been assayed (22). The densities of NR2A/B, but not NR1, subunits are higher in resected cortical areas with EEG-proven epileptogenicity as compared to neighboring nonepileptic cortex (Fig. 6.1). The NR2 subunit is colocalized with NR1 protein expression, providing evidence of a potential functional substrate for a hyperexcitable NMDA receptor. Moreover, recent evidence suggests a differential expression of the NR1-NR2B receptor complex in the postsynaptic region in epileptic dysplastic tissue increased association of the NR1-NR2b complex with the postsynaptic density protein PSD-95 (23).

dysplastic neurons. The degree of NR1 and NR2A/B receptor expression in focal epileptogenicity has been assayed (22). The densities of NR2A/B, but not NR1, subunits are higher in resected cortical areas with EEG-proven epileptogenicity as compared to neighboring nonepileptic cortex (Fig. 6.1). The NR2 subunit is colocalized with NR1 protein expression, providing evidence of a potential functional substrate for a hyperexcitable NMDA receptor. Moreover, recent evidence suggests a differential expression of the NR1-NR2B receptor complex in the postsynaptic region in epileptic dysplastic tissue increased association of the NR1-NR2b complex with the postsynaptic density protein PSD-95 (23).

In patients with temporal lobe epilepsy caused by hippocampal sclerosis, AMPA receptors are denser in both the internal and external molecular layers of the fascia dentata than in normal fascia dentata (24). The cause(s) of increases in AMPA receptor densities in human epilepsy are unknown; the increases may be a result of mossy fiber synapse ingrowth or may precede the sprouting.

Metabotropic Glutamate Receptors

Metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluRs) are second-messenger-coupled receptors that have diverse effects on the cellular and synaptic properties of nerve cells. Recent evidence suggests that mGluRs may play a role in the production of neuronal plasticity and epilepsy (25, 26, 27). The activation of mGluRs on astrocytes induces the release of glutamate through a calcium-dependent process, which reveals a pathway of regulated transmitter release from astrocytes and outlines the existence of an integrated glutamatergic crosstalk between neurons and astrocytes in situ that may play a critical role in epileptogenicity (28, 29, 30).

The mGluRs include at least eight receptor subtypes. These subtypes are grouped into three subclasses based on similarities in amino acid sequences, signal transduction mechanisms, and agonist selectivities (31). Various studies show evidence that activation of mGluR I subtype has proconvulsant effects and that activation of mGluR II and III subtypes results in anticonvulsant actions (25, 26, 27). Although the marked effects of mGluRs group I on epileptiform activity have been demonstrated experimentally, the relevance of these observations to seizure generation and epileptogenesis requires further studies in both animal models of seizures and epileptic human tissue.

GABA Receptors

In general, activation of the GABAergic system causes neuronal inhibition and prevents epileptiform activity. The GABA receptors are divided into two subtypes: GABAA and GABAB.

GABAA

In the CNS, the mature GABAA receptors are responsible for fast synaptic inhibition. Activation of the GABAA receptor opens a chloride channel, causing hyperpolarizing potentials. The abundance of excitatory synapses is paralleled by an impressive array of inhibitory cell-to-cell contacts. At least in cortical structures, inhibitory neurotransmission is mediated predominantly by the amino acid GABA release by different classes of interneurons on strategically localized postsynaptic structures. Thus, inhibitory inputs are found at the axodendritic, axosomatic, and even axoaxonic segments (32). Although most excitatory neurotransmission is meant to link relatively distant regions, most of the interneuronal networks belong to the so-called local circuitry (2). In neocortical and hippocampal structures of primates and rodents, the relatively repetitive morphologic appearance of principal cells differs from the cellular, morphologic, and structural diversity of GABAergic interneurons (32). In addition to modulating inhibition, GABA may act as a trophic factor (33) and excitatory neurotransmitter during early brain prenatal development.

The excitatory activity is related to the fact that resting membrane potentials are more negative than the average GABAA reversal potential (that is more positive during embryonic and early postnatal periods) (34, 35, 36, 37). The GABA potential results in the depolarization of the cell, leading to the activation of the voltage-gated calcium channels with increased Ca2+ in immature neurons (37, 38, 39). The depolarizing effects of GABA-receptor activation have been reported in immature cells from a number of brain regions, including the neocortex (37,40) and hippocampus (34, 35, 36,41). These results suggest that depolarizing GABA-mediated synaptic activity may act synergistically with NMDA receptor activation by providing the depolarization necessary to relieve the Mg2+ block of the NMDA channel. The presence of this synergistic effect during the early postnatal period and/or its persistence during the late postnatal period may provide a synaptic substrate for the neuronal hyperexcitability seen in early life or later-onset epileptogenicity. Age-dependent predisposition to epilepsy results in a variety of pediatric neurologic conditions associated with seizures, which may influence or determine the appearance of epileptic disorders later in life. Maturational changes in neurotransmitter and channel function should be taken into account in the process of identification of the cellular mechanisms of seizure initiation.

Considerable evidence suggests that impaired GABA function can cause seizures and may be implicated in some types of epilepsies. Altered GABAA receptor function may contribute to inherited or acquired epilepsies. Epilepsy may result from genetic predisposition that leads to a decrease in GABA-mediated inhibition (42). Recent studies on tissue resected from patients with mesial temporal lobe and neocortical epilepsy showed reductions in the GABAA receptors (43, 44, 45, 46). These results are discordant with those of other studies on human hippocampi resected from patients with temporal lobe epilepsy, which showed that GABA neurons are relatively preserved and their axons sprout into the supragranular layer for aberrant innervation of the

fascia dentata (47). Moreover, the postsynaptic GABA receptor protein densities were increased throughout the extent of the fascia dentata molecular layer as compared to normal controls (47).

fascia dentata (47). Moreover, the postsynaptic GABA receptor protein densities were increased throughout the extent of the fascia dentata molecular layer as compared to normal controls (47).

GABAB

GABAB is a G-protein-coupled receptor that can open potassium or close calcium channels (48,49). GABAB receptors are presynaptic or postsynaptic. GABAB-receptor activation may result in different effects depending on location. Activation of the GABAB-receptor-linked potassium channels results in prolonged hyperpolarization and leads to postsynaptic inhibition. On the other hand, the long duration of the GABAB-mediated potentials may be responsible for some epileptic effects, as GABAB agonists, such as baclofen, are reported to exacerbate the spike-wave discharges in generalized epilepsies. Absence seizures are believed to be generated by the interaction between the T-type (transient) calcium current (T-current), the GABAB-induced hyperpolarization, and the intrinsic bursting activities of the relay cells (50).

Acetylcholine Receptors

Cholinergic inputs may help trigger epileptiform activity. Studies show that cholinergic agonists such as pilocarpine can cause severe seizures in animals. These seizures may progress into status epilepticus (SE) and produce permanent neuronal loss and synaptic reorganization (51). The possible role of the acetylcholine receptor was illustrated by the description of an Australian family in which a missense mutation in one subunit of brain acetylcholine receptor is associated with nocturnal frontal lobe epilepsy (52,53).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree