Chapter 5 Medications used for anxiety and sleep disturbances

The information in this chapter will assist you to:

Introduction

In the treatment and management of anxiety, psychotherapy (particularly cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT)), combined with antidepressant medications (particularly the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and selective noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs)), are first-line options. Benzodiazepines and beta blockers are also used for time-limited anxiety problems or short-term management (Ohaeri 2006, Saeed et al 2007). See Table 5.1 for an overview of cognitive behavioural therapy. Many consumers find the combination of psychotherapeutic and pharmacological approaches to their anxiety helpful, and some find the option of psychotherapy alone to be more effective for managing their problem than the use of long-term medication.

Table 5.1 Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT)

| What CBT is | A commonly used psychotherapeutic approach that, as its name implies, focuses on a person’s cognition (thoughts) and behaviour (actions). It works to alter thought processes in order to produce desired changes in their feelings and behaviours. The emphasis in CBT is on challenging faulty assumptions and beliefs that the person has developed and teaching them coping skills that may be helpful in addressing their problems. It is a goal-directed and problem-focused therapy that focuses on present rather than past issues |

| What CBT is used for | Is often the treatment of choice for a range of mental health problems and has been used for managing depression, anxiety, schizophrenia, personality problems, eating disorders and bipolar disorder. It has also been found useful for insomnia, substance dependence and crisis intervention, and is used alone or in combination with medication, as either an individual or group therapy |

| Main features of CBT | CBT uses a range of structured cognitive techniques including questioning and challenging of assumptions and use of a diary to record events and associated thoughts, feelings and behaviours. Behavioural techniques include relaxation techniques and graded exposure |

The combination of CBT and pharmacotherapy is also the most common approach to the treatment and management of sleep disturbances (Krystal et al 2006, Suhl 2007). Attention to lifestyle and daily habits is important for both anxiety and sleep disturbances. Effective overall management of both groups of disturbances therefore involves comprehensive attention to adequate diet and exercise, reduction of caffeine and alcohol intake, adequate sleep and stress reduction and management, as well as psychotherapeutic and pharmacological options. This chapter provides an overview of pharmacotherapy for anxiety disturbances and outlines sleep disturbances with a focus on the pharmacological management of insomnia.

Anxiety

Anxiety disorders are associated with a person’s perception of the threat of harm to other people or themselves, in which ambiguous stimuli may be misconstrued or distorted. This produces emotional, behavioural and motor responses that can be severe and debilitating. These responses include autonomic nervous system activation, changes in muscle tone, ritualised behaviours, sleep disturbances and alterations in attention and concentration.

Anxiety disorders are considered the most common types of mental health problem with a reported incidence in the USA of 18% (Kessler et al 2005a, 2005b). The prevalence of anxiety disorders in Australia is reported at 12 women per 100 000 and 7 men per 100 000 of the population (AIHW 2006), with most developing during childhood and adolescence or young adulthood. Unfortunately, there is a significant problem with underdiagnosis and therefore under-treatment of this group of disorders (Nash & Nutt 2007). This may be due, in part, to a perception by the general public that symptoms of anxiety are ‘normal’ or to be expected and tolerated so that they do not seek help for them. However, while they have sometimes been considered to be milder or less severe than other mental health problems, particularly those of psychotic depth, anxiety disturbances are often chronic mental health problems associated with significant personal distress and difficulty in managing daily functioning.

Anxiety disturbances have been associated with higher risk of suicide and substance abuse/dependence, poorer physical health, difficulties with sleep and problems with marital/relationship functioning (Ohaeri 2006). As noted in Chapter 4, they are also significantly co-morbid with depression. There are a number of forms of anxiety disturbance including panic attacks, social anxiety disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder, specific phobias, obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) and generalised anxiety disorder (see Chat box 5.1). While they produce a similar profile of responses, the triggers and duration of symptoms can vary greatly. Currently, there is some debate about whether OCD belongs to the group of anxiety disturbances. Pollack et al (2007) report that it may be better understood as belonging to a group of obsessive–compulsive spectrum disorders that are being considered as a separate diagnostic category in the forthcoming fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (i.e. DSM V). The major characteristics of anxiety disturbances are summarised in Table 5.2.

Table 5.2 Categories of common anxiety disorders

| Anxiety Disorder | Clinical features |

| Panic disorder | Sudden, spontaneous short-lived episode of intense anxiety |

| Agoraphobia | Feelings of anxiety in situations where escape or help may be difficult (e.g. outside the home, on public transport, in crowded public places) |

| Specific phobia | Fear or avoidance of specific situations or objects (e.g. fear of spiders, flying or needles) |

| Social phobia | Specific phobia associated with social situations that involve meeting new people, public performance or eating in public |

| Obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) | Unreasonable thoughts and fears experienced when engaging in recurrent, ritualised, seemingly purposeless behaviours to reduce the anxiety |

| Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) | Anxiety following exposure to an extreme, traumatic or catastrophic event |

| Generalised anxiety disorder | Anxiety not associated with a specific event, object or situation |

Adapted from Anxiety disorders and panic states, eMIMS 2007, by J S Olver and G D Burrows 2006, CMPMedica Australia

Pathophysiology of anxiety disturbances

Human and animal studies investigating the neurobiology of fear, anxiety and aggression have shown that the amygdala is a key brain centre involved in the processing and expression of these emotions. The amygdalae are located bilaterally in the medial temporal lobes. The amygdala is also involved in emotional memory and the recognition of emotional states in other people. When the amygdalae are damaged, the affected person experiences a flattened affective state.

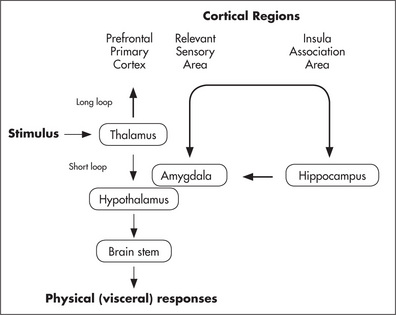

It has been proposed that the processing of fear and anxiety involves two pathways: the short loop or ‘low road’ and the long loop or ‘high road’ (Ohman 2005, LeDoux 1996). The short loop generates responses instantaneously to a stimulus, such as freezing and autonomic activation, that place the body on alert. Information is received by the thalamus and transferred to the amygdala, which in turn activates the hypothalamus and brain stem to initiate the visceral and behavioural responses. The long loop involves more conscious processing of the information, and considered decisions are made as to the nature of the stimulus and the appropriate level of responsiveness to follow. In this pathway there is interplay between the amygdala and cortical regions (prefrontal area, sensory cortex and insula) in the processing of the information (see Fig 5.1).

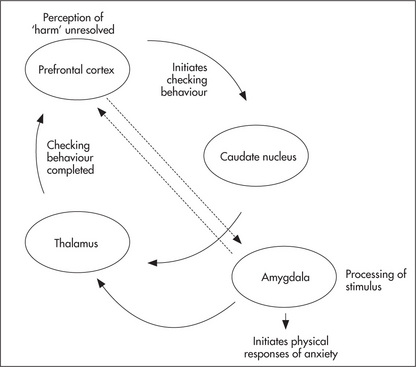

The caudate nucleus of the basal ganglia is also implicated in anxiety states, particularly OCD. The caudate nucleus plays a role in automatic checking behaviours associated with familiar procedural tasks. These checking behaviours are part of well-learned procedures that usually happen below the level of conscious awareness and are aimed at minimising harm or threat. Examples are turning off the stove after cooking and locking a door as you are leaving your home. It has been proposed that in OCD, this implicit process becomes explicit. In other words, checking behaviours become conscious and deliberate acts. The current model of OCD pathophysiology (Neel et al 2002) suggests that two reinforced loops become established in the brains of affected persons (see Fig 5.2). The prefrontal cortex perceives a threat and consciously activates the caudate to initiate checking behaviours. This information passes back through the thalamus to the prefrontal cortex, but the perceived threat is not yet extinguished. The loop is activated again – resulting in compulsive, ritualised checking. The prefrontal cortex also activates the amygdala, resulting in an enhanced anxiety state. This feeds back through the thalamus to the prefrontal cortex, which can then further activate the amygdala. There is clearly interplay between these two loops as there is overlap between the brain regions involved. Neuroimaging studies have shown that the prefrontal areas of people affected with OCD show a larger volume than those without the disorder. It has been suggested that the larger regional volume may be due to poor ‘pruning’ of redundant neuronal connections early in development that predisposes these individuals to the establishment of such loops (Neel et al 2002, Rosenberg & Keshavan 1998).