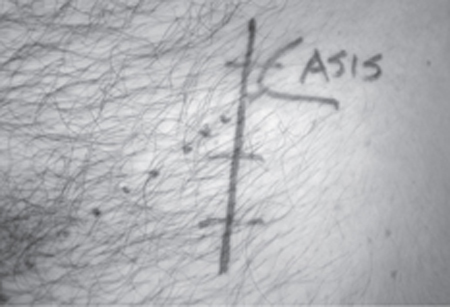

36 Meralgia Paresthetica A 39-year-old male auto mechanic presented with a 4-month history of constant numbness over the left lateral thigh. Two months after noting this abnormal sensation it intermittently changed to a pruritic and severely dysesthetic sensation deep in the same area for a period of several weeks, at its worst in the evening. In addition to this sensory disturbance, the patient intermittently experienced sharp pain in the left groin over the anterior aspect of the hip. This pain was worst when his intra-abdominal pressure was elevated, as in coughing or sneezing. There was no back pain or radicular pain. Neurological examination revealed a well muscled male with no signs of atrophy or fasciculation in the lower limbs. Motor testing was normal. Sensory examination revealed an area of altered response to light touch and pinprick over the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve (LFCN) distribution on the left. Ankle and knee reflexes were normal. There was local tenderness and a positive Tinel sign (LFCN distribution dysesthesia) when the area just medial to the left anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) was percussed. There were no inguinal or abdominal hernias present on groin examination. He had normal lumbar spine examination and negative femoral stretch tests and straight leg raising. Hip rotation and range of movement were full and nonpainful. Left LFCN nerve conduction was delayed relative to the right side on electrodiagnostic testing, whereas femoral nerve testing was found to be normal bilaterally. The patient was diagnosed with meralgia paresthetica (MP). The treatment options for MP were discussed with the patient, who, after consideration, chose to accept local anesthetic and steroid perinerve infiltration at the painful site medial to the ASIS. A solution of 9 mL of 0.5% Marcaine (AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals LP, Wilmington, DE) and 1 mL of 40 mg/mL Depo-Medrol (Pfizer, Inc., New York, NY) was injected one fingerbreadth medial to the ASIS on the left, once per week on three separate occasions. At follow-up, he had marked attenuation of his painful dysesthesias but continues to exhibit sensory alteration with hypoesthesia to pinprick in the LFCN distribution. A 68-year-old male presented with a 10-year history of progressive left lateral thigh pain. Originally, it was a mild “electrical” pain and occurred in short, intermittent episodes. At the time of referral the pain had progressed to a severe “electrical and stretching” sensation that occurred for seconds to minutes many times every day. The patient also noted a subjective change in sensation perception over the left lateral thigh. He denied any back pain, urinary, bowel, or radicular symptoms. The patient was a nondiabetic, nonobese, and in excellent physical condition. He was now finding the symptoms to be very disruptive to his daily activities. On examination there was a subtle alteration in pinprick sensation over the left LFCN distribution. There was no evidence of radiculopathy or myelopathy. The diagnosis of MP was made and treatment options were discussed with the patient. Analgesics, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents, tricyclic antidepressants, and gabapentin had failed to alleviate his symptoms. He chose a course of nerve block as the next line of therapy. At 1 week following the second injection the patient’ s symptoms were well controlled with minimal residual numbness. He opted to forgo a third injection. Two months after the second injection the patient experienced a worsening of the left lateral thigh pain while sitting at home. He described this pain as unbearable, sharp searing pain. When this sensation subsided he was left with a persistent pain in the left lateral thigh. On examination there was hypoesthesia over the LFCN distribution. A third injection was performed, and a low-strength narcotic preparation was prescribed as needed for pain. The patient returned to the clinic with no relief 1 month after the last injection. Because an adequate course of conservative therapy and medication had been utilized, surgery was suggested. One month following this decision, the patient underwent surgical decompression of the LFCN. The nerve was visualized medial and slightly inferior to the ASIS. The LFCN was tightly compressed under the inguinal ligament. The inguinal ligament superior to the LFCN was divided and the LFCN was released over a considerable length. At follow-up, the patient continues to have acceptable relief of his pain. Meralgia paresthetica The LFCN arises from the L2 and L3 posterior roots. The nerve emerges at the lateral border of the psoas. It courses superficial to the iliacus, deep to the fascia in the iliac fossa. It then passes into the thigh medial to the ASIS, posterior to the lateral end of the inguinal ligament, and anterior to the iliacus. Approximately 10 cm distal to the inguinal ligament, the nerve pierces the fascia lata of the thigh and divides into anterior and posterior branches, which supply the anterolateral thigh superior to the knee. The nerve is 2 to 3 mm in diameter and can be located in the groove between the sartorius and iliacus muscles at 1.5 to 2.0 cm distal to the inguinal ligament. This normal anatomy was found in ˜80% of bodies in a cadaveric study. There are four main anatomical variants to the LFCN: The LFCN may also be absent (7%), with sensory branches of the femoral or ilioinguinal nerves supplying the LFCN distribution. A typical history will reveal varying degrees of neuralgic pain and altered sensation over the LFCN distribution in the anterolateral thigh. This sensation may be exacerbated by hip extension and improved by hip flexion. Other patients note worsening of symptoms by activity and relief by rest. In some cases the skin over the LFCN distribution will be denuded of hair by constant rubbing in an attempt to relieve the pain. The LFCN distribution is often dysesthetic to light touch and may be anesthetic to pinprick. Palpation at the ASIS and along the inguinal ligament may reproduce symptoms or elevate discomfort. Injection of local anesthetic at this tender point will often temporarily alleviate these symptoms. Bowel and bladder dysfunction, lumbar pain, positive nerve root irritation (femoral stretch and straight leg raise test), sensory deficits beyond the anterolateral thigh, and any motor symptomatology must be ruled out on history and physical examination to exclude central or radicular causes of the problem. Most cases are idiopathic, and patients may be predisposed by the congenital variants discussed earlier or superimposed risk factors, including the following: There is a significant differential diagnosis of patients presenting with pain and sensory alteration in the lateral thigh. These include the following: The diagnosis of MP is essentially a clinical one. If musculoskeletal or tumor pathology is being seriously considered, appropriate bony or soft tissue imaging of the spine, hip, and pelvis is obtained to rule out more sinister conditions. In addition to clinical examination, some clinicians choose to obtain objective data to solidify the diagnosis of MP by completing somatosensory evoked potentials. This technique records central sensory response to stimuli presented over the distribution of the LFCN. To rule out radicular involvement, responses are recorded for the anterolateral and medial thigh, both of which are innervated by L2–3 roots. These responses are duplicated in the contralateral thigh for comparison. In MP, there will be a delayed or absent response in the LFCN distribution, with normal conduction in the ipsilateral medial thigh and contralateral entire thigh. Electrodiagnostic tests may also be used to rule out femoral nerve involvement. Recently, a computerized pressure specifi c sensory testing device has been described as useful in documenting LFCN dysfunction; however, this technique is under development. The management of MP occurs in a stepwise approach, beginning with risk factor modification and interval examination, pharmacological therapy, anesthetic/corticosteroid injection, and finally surgery. Risk factor modification includes changing clothing to looser-fitting pants and belts, weight loss, and removing wallets from the back pocket. The patient is also advised to avoid rigorous activity that involves hip extension. Ice packs can be applied to the site of maximal tenderness for 30 minutes three times a day. Obese patients are encouraged to lose weight. A nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory may be added for several weeks, and if this fails a trial of a tricyclic agent. The patient is then seen in the clinic in 2 months. Fifty percent of patients will be relieved of symptoms after risk factor modification and/or appropriate pharmacological therapy. If symptoms persist, the next step is injection of corticosteroid and local anesthetic. Local anesthetic and corticosteroid may be mixed and injected at the point of maximal tenderness to palpation. The injection is made perpendicular to the skin and fanned outward under the fascia lata. This procedure will provide immediate relief of symptoms. The injection is repeated weekly for 3 weeks. The patient is then reassessed 6 to 8 weeks following the final injection. Surgical treatment of MP is reserved for intractable cases that severely limit the patient. Surgical treatment is based on the anatomy of the LFCN; hence exploration of the nerve is required at the inguinal ligament. Depending on the presence of pathology (i.e., neuroma) and compressive anatomy of the LFCN, a decompression may suffice, or neurectomy may be considered. The surgical approach to the LFCN requires a 5 cm vertical incision starting just above and mostly inferior to the lateral aspect of the inguinal ligament (Fig. 36–1). The fascia lata overlying the sartorius muscle is then divided and retracted in the same direction over the sartorius muscle, with care not to divide branches of the LFCN on the muscle surface. The nerve is identified and followed proximally toward its position near the lateral attachment of the inguinal ligament to the ASIS (Fig. 36–2). The inferior attachment of the split inguinal ligament is divided with sharp dissection. Dissection is carried on ˜2 cm medially to open the iliac fascia at its attachment to the inguinal ligament. The iliacus muscle is visualized and bluntly dissected medially to ensure complete decompression.

Case Presentation

Case Presentation

Case 1

Case 2

Diagnosis

Diagnosis

Anatomy

Anatomy

Characteristic Clinical Presentation

Characteristic Clinical Presentation

Differential Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

Diagnostic Tests

Diagnostic Tests

Management Options

Management Options

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree