NTD

Description

Burden, availability of treatment

Dengue

Flavivirus (RNA virus). Mosquito borne (genus Aedes). Fever, bone pain, haemorrhagic complications, shock

Fifty to 100 million cases yearly worldwide. >20,000 deaths. No treatment, vaccine under trial

Rabies

Lyssavirus (RNA virus). Transmitted by bite of infected dog or other mammal. Causes fatal encephalitis

Estimated 55,000 deaths per year. Vaccine preventable (ore and postexposure)

Trachoma

Chlamydia trachomatis (bacterium). Direct transmission, linked to poor hygiene

Six millions blinds worldwide. Easily curable with azithromycin single dose (international donation)

Buruli ulcer

Mycobacterium ulcerans (bacterium). Devastating skin ulcers, bone lesions

Underestimated, probably tens of thousands cases in at least 36 countries. Anti-mycobacterials, surgery

Endemic treponematosis

Treponema pertenue, T. endemicum, T. carateum (bacteria). Cutaneous and mucosal lesions, often devastating

Thousands of cases but rapidly declining. Penicillin, other antibiotics. Targeted for elimination

Leprosy

Mycobacterium leprae (bacterium). Skin and mucosal lesions, peripheral nerve involvement. Stigmatizing

About 200,000 new cases in 2010. Multi drug treatment regimens for years

Chagas disease

Trypanosoma cruzi (protozoan). Transmitted by faeces of blood-sucking infected bugs, or more rarely by oral route, transfusion or transplant. Chronic cardiac and gastrointestinal complications

Estimated prev. 10 million cases with 12,500 yearly deaths in Latin Americans. Treatment with benznidazole or nifurtimox, more effective in early stage, toxic

Human African Trypanosomiasis

Trypanosoma brucei (protozoan). Transmitted by Glossina (“tse tse”) flies. T.b. gambiense causes sleeping sickness, chronic, fatal if untreated

Declining. Estimated 7,000 new cases in 2010. Treatment improved in recent years with combination eflornithin-nifurtimox

Leishmaniasis

Genus Leishmania (protozoan), several species. Transmitted by phlebotomus flies. Cutaneous, muco-cutaneous and visceral forms, the latter fatal if untreated

About 2 million new cases/year, ¼ visceral. Present also in temperate climates. Oral treatment (miltefosine) available in recent years

Cysticercosis

Taenia solium (worm, tenia of the pig). Can cause epilepsy and other neurological symptoms

Fifty to 100 million persons infected with T. solium. Treatment with albendazole or praziquantel, not always effective

Dracunculosis

Dracunculus medinensis (worm). Transmitted via drinking water contaminated with a small shellfish, intermediate host. Causes abscess-like skin lesions

Close to eradication, elimination achieved in most countries

Echinococcosis

Echinococcus granulosus (worm, tenia of dog and sheep). hydatid cysts in liver, lungs or other organs (rarely brain)

About 200,000 new cases per year. Treatment with oral albendazole or local injection of hypertonic fluid or surgery

Filariasis

Wuchereria bancrofti, Brugia malayi, Loa loa and other (worms). The former two, transmitted by mosquitoes, cause the nocturnal, lymphatic form (lymphedema, elephantiasis), while Loa loa, transmitted by Chrysops fly, causes the diurnal form (migrant oedema, other manifestations)

About 120 million cases of lymphatic form, and 12–13 million cases of loiasis. Treatment with ivermectin, albendazole, DEC. Declining thanks to mass treatment (donation programmes) and vector control

Onchocerciasis

Onchocerca volvulus (worm). Transmitted by Simulium fly. Skin lesions, generalized itching. Ocular lesions cause blindness

About 500,000 blind people in the world. Declining thanks to mass treatment with ivermectin (donation programme)

Schistosomiasis

Genus Schistosoma (worm), several species. Acquired bathing in freshwater harboring snails acting as intermediate hosts. Infective larvae penetrate intact skin. Cause of several distinct clinical syndromes according to species and organ involved

Prevalence of about 200 million cases, and at least 40,000 deaths per year (underestimated). Declining due to mass treatment with praziquantel

Soil transmitted helminths

Comprise different nematode worms, classically: Ascaris lumbricoides and Trichuris trichiura (acquired via ingestion of food contaminated with soil), Ancylostoma duodenale and Necator americanus (acquired via penetration of larvae through intact skin). Strongyloides stercoralis (acquired as the latter two) recently added to WHO list among “other neglected tropical conditions”. Variety of gastrointestinal symptoms, failure to thrive, severe anemia, respiratory problems

Estimated over a billion people infected. Mass treatment programme ongoing with mebendazole, albendazole and other drugs, but poorly effective against Strongyloides

2.1 Dengue, Leishmaniasis, Onchocerciasis

Dengue is currently considered a pandemic disease. It is estimated to cause 50–100 million cases and >20,000 deaths annually worldwide. It is caused by a Flavivirus and transmitted by the bite of a mosquito of the genus Aedes, such Aedes aegypti or Aedes albopictus. The latter is increasingly common in temperate climates and autochthonous cases of dengue have already been reported in the USA and Western Europe, including some local epidemics. A mild febrile disease (dengue fever) may become a fatal threat (dengue haemorrhagic fever and dengue shock syndrome) in case of secondary infection with a different viral serotype. Therefore, particularly at risk are frequent travellers (especially to Asia and Latin America) and the so-called VFR (“visiting friends and relatives”) travellers, a definition which includes immigrants who briefly visit their country of origin. Moreover, travellers and migrants entering a non endemic country during the acute phase of infection may be the source of transmission to the local population in the presence of a suitable vector.

No etiologic treatment is available. Vaccines are under study, but not yet at the stage of a Phase III clinical trial. Dengue is not primarily a disease of the nervous system, but several case reports of dengue-associated encephalopathy have been published (Kanade and Shah 2011), as reviewed in Misra and Kalita (2014).

Leishmaniasis is not a single disease but a group of diseases caused by different species of protozoa of the genus Leishmania, and transmitted by sandflies in all continents, including the Mediterranean areas of Europe. Two main forms of the infection are known, cutaneous (including muco-cutaneous) and visceral. The latter is a life-threatening disease affecting the bone marrow and the reticulo-endothelial system, closely simulating a haematologic malignancy: fever, huge splenomegaly and secondary pancytopenia. Central nervous system (CNS) involvement is uncommon, but neurological signs and symptoms (both central and peripheral) have been reported in the disseminated form of the disease, which usually affects immune-suppressed patients, especially in HIV co-infection (Walker et al. 2006).

Leishmaniasis is not among the most common travel-related infections in travellers, though cases (of both the main presentations) are regularly reported in European travellers (Odolini et al. 2012).

Echinococcosis in humans is caused by the tapeworms E. granulosus (“cystic echinococcosis”) and E. multilocularis (“alveolar echinococcosis”). Human infection occurs accidentally by ingestion of Echinococcus eggs excreted with the faeces of the definitive host (dogs, foxes) (McManus et al. 2012). The cysts mostly develop in the liver and/or in the lungs (>90 % of cases), but other sites can be involved. For instance, localization in the spinal cord and brain can cause neurological symptoms, such as seizures or paralysis (Brunetti and White 2012). Another tapeworm which can rarely infest humans is Taenia multiceps, which causes coenurosis (Ing et al. 1998). The cysts usually settle in the CNS, eye, muscles or subcutaneous tissue. The signs and symptoms caused by the CNS localization of coenurosis resemble those of neurocysticercosis (see Carpio and Fleury 2014), from which coenurosis is indistinguishable at computerized tomography/magnetic resonance imaging. The only method to differentiate cestode cysts is surgical removal and subsequent microscopic examination.

Transmission of E. multilocularis is limited to the northern hemisphere, while Echinococcus granulosus is widely diffused, especially in parts of Eurasia, South America and north east Africa (McManus et al. 2012). The risk of echinococcosis in travellers to specific countries is difficult to define clearly due to the broad diffusion of the disease.

Onchocerciasis as a cause of neurological involvement is discussed in Njamnshi et al. (2014). The most common symptoms of this infection are cutaneous (generalized pruritus with a variety of skin lesions). The ocular involvement is characterized by corneal lesions. Onchocerciasis has been reported as the most common filarial infection affecting travelers and immigrants treated in the clinics belonging to the Geosentinel network (Lipner et al. 2007). Although the disease occurs much more frequently, as expected, in immigrants and long-term expatriates than in tourists, some cases have also been observed in tourists after short exposure.

3 Rabies

France had been declared rabies-free since 2001, and Cracotte was a pet dog that had always been living in that country. However, when on February 2008 it presented behavioural changes and bit two people, rabies was suspected and then confirmed. Subsequent investigations were conducted, in order to identify the possible index case. Cracotte’s owners had a second dog, Youpee, which had died in January after showing symptoms compatible with rabies. Presumably, Youpee had acquired the infection from a dog named Gamin, the probable index case, illegally introduced into France from Morocco. Both Youpee and Gamin had been incinerated and not tested, although they had symptoms compatible with rabies. After the diagnosis of rabies in Cracotte, the health and veterinary authorities traced people and animals that might have been exposed, and offered the prophylaxis. Neither human nor other animal cases in relation to this event were reported (Team FMI 2008).

Rabies is invariably fatal. It is therefore essential to focus on prevention, which includes behavioral measures (i.e., avoiding potentially infected animals) and pre-exposure immunization. Post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) is also available, and should be administered as soon as possible in case of exposure to rabies virus.

According to WHO standards, the vaccine schedule is in three doses on days 0, 7, 28 (WHO, http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs099/en/). When a subject gets in contact with a suspect rabid animal, the measures to be taken depend on the type of contact (Table 2), the likelihood of the animal being rabid (including its clinical features) and its availability for observation and laboratory testing. Immediate cleaning of the wound with water and soap or other available substances (detergent, povidone iodine) has proven effective in increasing survival rates.

Table 2

WHO guidelines for rabies post-exposure prophylaxis

Category | Exposure to rabid animala | Treatment |

|---|---|---|

I | Touching or feeding; licked unbroken skin | None |

II | Nibbled uncovered skin; minor scratches or abrasions without bleeding | Local treatment of the wound and immediate vaccination |

III | One or more transdermal bites or scratches; licked broken skin; contamination of mucous membrane with saliva from licks; any degree of exposure to potentially rabid bats | Local treatment of the wound, immediate vaccination, and administration of rabies immunoglobulin |

If a previously vaccinated person is bitten by a rabid animal, only two booster doses with vaccine on days 0 and 3 are indicated as PEP. In case the exposed person had not been vaccinated, the vaccine doses should be four: on days 0, 3, 7, 14. In case of category III exposure (Table 2), also immunoglobulins should be administered as soon as possible, injecting them in part around the wound, and in part intramuscularly, distant from the anatomic site of vaccine injection.

An estimated 10–16 million people undergo rabies PEP worldwide every year (Both et al. 2012). Death of a patient who has received PEP is rare, and usually results from inadequate prophylactic regimen, that may occur. Unfortunately, many subjects who get exposed in Africa and Asia receive inadequate PEP because of low availability and high cost of immunoglobulins. This is an additional reason to promote the vaccination in travellers, who still do not seem to be sufficiently covered by vaccination (Gautret and Parola 2012). The case reported above (Team FMI 2008) reminds us that diseases are not strictly confined within the borders of a country because people and animals migrate and travel.

Although rabies is ubiquitous, the highest incidence is in Africa and Asia, where most of human deaths caused by this virus occur (about 95 %). WHO estimates 55,000 human deaths worldwide every year, but this is probably an underestimate because of misdiagnosis and lack of efficient surveillance system in endemic countries (Both et al. 2012). According to a recent review (Gautret and Parola 2012), 48 confirmed cases of rabies have been reported in tourists/migrants returned to Europe and the USA from 1990 to May 2012, and this is also probably an underestimate. People travelling to rural areas or areas heavily populated with stray dogs in those countries are at highest risk.

Dogs remain the main source of rabies, but monkeys are also a common source in developing countries, probably because travelers very often are not aware of the risk related to a monkey bite.

3.1 When to Suspect Rabies

History of animal bite/scratch is usually a key point. Although symptoms usually develop from 1 to 3 months from the virus inoculation, it should be kept in mind that a longer incubation period (>1 year) is also possible.

Compatible clinical signs (see Jackson 2014). Unfortunately, when symptoms are present the disease is fatal.

3.1.1 Prevention in Travelers

Avoid contacts with wild animals. Vaccination, as described above.

4 Chagas Disease

S.A.Z.F., an Ecuadorian woman, migrated to Italy in 1999. In 2002, when she was 46 years old, migraine with aura started and she underwent cerebral computed tomography (CT) which only revealed a right parietal angioma. In 2003 and 2005 she was hospitalized in a neurological ward for severe migraine attacks accompanied by visual aura and motor symptoms. The last attack was characterized by right hemisyndrome and right homonymous lateral hemianopsia. Cerebral magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed ischemic lesions of the Ammon’s horn, basal ganglia and left cerebral peduncle. Thromboembolia was suspected and hypokinetic dilatative myocardiopathy with left apical ventricular thrombus was diagnosed by echocardiography. In the work-up, serology for Chagas disease was done with positive result. The cardiac ejection fraction was not severely impaired (40–45 %) but an apical wall akynesia and inferior-basal hypokynesia were present. At the anamnesis the patient referred a lipothymia with loss of consciousness in 2000. A 24 h electrocardiogram recording showed premature repetitive atrial and ventricular beats. The patient was treated with oral anticoagulants and the ventricular thrombus disappeared. After some months, only the homonymous lateral hemianopsia persisted, with marked hypostenia without motor symptoms. PCR for Trypanosoma cruzi in the peripheral blood gave negative results. Even in the absence of strong evidence in the literature, she was treated with benznidazole (5 mg/kg) for 60 days in 2005. In the follow-up until 2011 the patient continued to have positive Trypanosoma cruzi serology (repeated every 2 years) with progression of the myocardiopathy and is now candidate to heart transplant.

Chagas disease (CD) or American trypanosomiasis, is a complex zoonosis, endemic in continental Latin America, caused by the hemoflagellate Trypanosoma cruzi (Fig. 1) (see Coura 2014). Transmission to humans is primarily vectorial, mediated by various species of triatomine insects (blood-sucking bugs), but other non-vectorial mechanisms of transmission are possible (blood transfusion, cells/tissues/organs transplant, vertical transmission (from mother to infant) and with food contaminated by vector dejections) (Prata 2001). According to WHO estimates, about ten million people are affected by this plague (WHO, http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs340/en/index.html) and about one-fifth of the population is considered at risk in 21 Latin American countries (Argentina, Belize, the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, El Salvador, French Guyana, Guatemala, Guyana, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, the Plurinational State of Bolivia, Suriname and Uruguay).

Fig. 1

Detection of a trypomastigote of Trypanosoma cruzi in blood by the Quantitative Buffy Coat (QBC) technique (photo by Maria Gobbo, CTD)

At present, CD ranks first among parasitological diseases for impact on health and social systems in endemic areas (Hotez et al. 2008) due to its effects on the productivity of people of working age and to disability and mortality. In the last 20 years, many factors contributed to a dramatic change in the epidemiological profile of CD, and these include implementation of different control initiatives in Latin America, sharp rise in international travels and migration, urbanization and internal migration in endemic countries among others (Schmunis and Yadon 2010). In the context of non-endemic countries, Europe is not spared, and the majority of cases are recorded in Spain and Italy (Guerri-Guttenberg et al. 2009).

CD is a neglected tropical disease with particular clinical features. The acute form is frequently asymptomatic or pauci-symptomatic (more than 95 % of cases), therefore contributing to underdiagnosis, and evolves into a chronic form, without any clinical manifestation, which can last for decades. In 20–30 % of cases, however, through a complex interaction between parasite and immune system, patients develop lesions in target organs (mainly myocardiopathy, dysrhythmias, megaviscera, cerebrovascular accidents). In this phase the haemoprotozoan is rarely found in the blood.

Disease expression is especially severe in immune-deficient patients such as organ transplant recipients, patient under immune-suppression or HIV-seropositive patients.

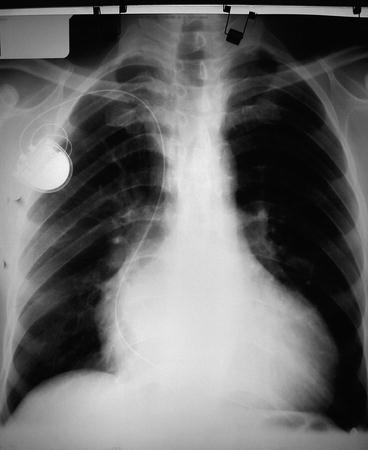

The CNS is involved in the rare symptomatic severe acute forms of CD, in the reactivation during HIV-linked immune deficiency (encephalitis) or during the chronic phase (ischemic stroke), the latter being the commonest (see Coura 2014). Several epidemiological studies have indeed shown a correlation between ischemic stroke and CD. Chronic cardiac form of CD may be characterized by cardiomegaly (Fig. 2), heart failure, mural thrombosis, apical aneurism or arrhythmias, all risk factors for stroke. However, stroke may be rarely the first signal of CD in asymptomatic patients without heart systolic dysfunction (Carod-Artal and Gascon 2010; Paixao et al. 2009).

Fig. 2

Chest X-rays of a Chagasic patient with cardiomegaly

4.1 When to Suspect Chagas Disease?

Accurate evaluation of epidemiological risk for CD such as Latin American origin; to be born from Latin American mother (to be considered also in adoptees); to have been transfused in Latin America; to be transplant-recipient from Latin American donor; travel to Latin America with a lifestyle at risk of infection (adventurous travel at risk for contact with vectors, drinking non-pasteurized fruit or sugar juices).

CD can be suspected in symptomatic people with epidemiological risk, but it has been demonstrated that it is cost-effective to test for CD in asymptomatic conditions only for pregnant Latin American women (Sicuri et al. 2011);

Travellers from Latin America with fever (associated or not with oedemas, malaise, increased liver enzymes, lactic dehydrogenase elevation), presence of Romaña sign (unilateral painless periorbital swelling and conjunctivitis);

Newborn form Latin American mother with general signs of infection (beginning from low APGAR score at birth);

Myocardiopathy or arrhythmia in a patient with epidemiological risk for CD (see above);

Digestive disorders (especially megaviscera in the digestive tract, achalasia-like disturbances, colopathy) in a patient with epidemiological risk for CD (see above);

Fever-associated or not to myocarditis/encephalitis/panniculitis in immune-suppressed or HIV-seropositive patients with epidemiological risk for CD (see above).

4.1.1 Treatment

Treatment of CD is limited to two drugs: nifurtimox and benznidazole. The latter, better tolerated, is considered the first choice. Currently, only a few methodologically rigorous trials have been conducted to study the efficacy of CD treatment (Marin-Neto et al. 2009). The complex history of the disease, unavailability of cure biomarkers, the need of prolonged follow-up to record clinical outcomes (such as myocardiopathy evolution, arrhythmias) contribute to limit the possibility to collect evidences with randomized controlled clinical trials.

4.1.2 Prevention in Travellers

No vaccine is available. Triatomine bites (generally at nighttime) should be prevented by sleeping under pyrethroid-impregnated bed nets avoiding lodges not adequately insulated or stuccoed. Moreover, drinking fresh, non-pasteurized fruit or sugar cane juices should be avoided.

5 African Trypanosomiasis

A 54-year-old nun who had lived for 30 years in the Central African Republic consulted the Centre for Tropical Diseases (CTD) in Negrar, Verona (Italy) for recurrent fever, headache, insomnia, and fatigue. At presentation, she was afebrile, with a huge spleen and marked pancytopenia. A quantitative buffy coat (QBC) for malaria was negative, and she was discharged. The working diagnosis was Hyper reactive Malarial Splenomegaly (HMS). Three days later she returned with fever. A QBC test turned out to be negative for malaria but showed the unexpected finding of trypanosomes. Similar forms were then found in peripheral blood smears. Serology results for T. brucei was positive. Results of CSF examination were normal (Bisoffi et al. 2005).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree