Mood disorders

Classification of mood disorders

The epidemiology of mood disorders

The aetiology of mood disorders

The acute treatment of depression

The longer-term treatment of mood disorders

The assessment of depressive disorders

The management of depressive disorders

The management of manic patients

Introduction

The mood disorders are so called because one of their main features is abnormality of mood. Nowadays the term is usually restricted to disorders in which this mood is depression or elation, but in the past some authors have included states of anxiety as well. In this book, anxiety disorders are described in Chapter 9. Mood disorders have in the past been referred to as ‘affective disorders’, a term that is still used fairly widely.

Depression

It is part of normal experience to feel unhappy during times of adversity. The symptom of depressed mood is a component of many psychiatric syndromes, and is also commonly found in certain physical diseases (e.g. in infections such as hepatitis, and some neurological disorders). In this chapter we are concerned neither with normal feelings of unhappiness nor with depressed mood as a symptom of other disorders, but with the syndromes known as depressive disorders.

The central features of these syndromes are:

• depressed mood

• negative thinking

• lack of enjoyment

• reduced energy

• slowness.

Of these, depressed mood is usually, but not invariably, the most prominent symptom.

Mania

Similar considerations apply to states of elation. A degree of elated mood is part of normal experience during times of good fortune. Elation can also occur as a symptom in several psychiatric syndromes, although it is less widely encountered than depressed mood. In this chapter we are concerned with a syndrome in which the central features are:

• overactivity

• elevated or irritable mood

• self-important ideas.

This syndrome is called mania. Some diagnostic classifications distinguish a less severe form of mania, known as hypomania (see below).

Clinical features

Depressive syndromes

The clinical presentations of depressive states are varied, and they can be subdivided in a number of different ways. In the following account, disorders are grouped by their severity. The account begins with a description of the clinical features of an episode of severe depression, together with certain important clinical variants that can influence the presentation of depressive disorders. Finally, the special features of the less severe depressive disorders are outlined. What constitutes an ‘episode’ of clinical depression is inevitably a somewhat arbitrary concept. The symptoms listed for the diagnosis of ‘depressive episode’ in the ICD-10 classification and the various levels of severity are shown in Table 10.1. Table 10.2 shows the criteria for ‘major depressive episode’ in DSM-IV.

Severe depressive episode

In a severe episode of depression, the central features are low mood, lack of enjoyment, negative thinking, and reduced energy, all of which lead to decreased social and occupational functioning.

Table 10.1 Symptoms needed to meet the criteria for ‘depressive episode’ in ICD-10

Appearance

The patient’s appearance is characteristic. Dress and grooming may be neglected. The facial features are characterized by a turning downward of the corners of the mouth, and by vertical furrowing of the centre of the brow. The rate of blinking may be reduced. The shoulders are bent and the head is inclined forward so that the direction of gaze is downward. Gestural movements are reduced. It is important to note that some patients maintain a smiling exterior despite deep feelings of depression.

Table 10.2 Criteria for major depressive episode in DSM-IV

Mood

The mood of the patient is one of misery. This mood does not improve substantially in circumstances where ordinary feelings of sadness would be alleviated—for example, in pleasant company or after hearing good news. Moreover, the mood is often experienced as different from ordinary sadness. Patients sometimes speak of a black cloud pervading all mental activities. Some patients can conceal this mood change from other people, at least for short periods. Some try to hide their low mood during clinical interviews, which makes it more difficult for the doctor to detect. The mood is often worse first thing in the morning when the patient wakes, improving a little as the day wears on. This is called diurnal variation of mood.

Depressive cognitions

Negative thoughts (‘depressive cognitions’) are important symptoms which can be divided into three groups:

• worthlessness

• pessimism

• guilt.

In feeling worthless, the patient thinks that he is failing in what he does and that other people see him as a failure; he no longer feels confident, and he discounts any success as a chance happening for which he can take no credit. Pessimistic thoughts concern his future prospects. The patient expects the worst. He foresees failure in his work, the ruin of his finances, misfortune for his family, and an inevitable deterioration in his health. These ideas of hopelessness are often accompanied by the thought that life is no longer worth living and that death would come as a welcome release. These gloomy preoccupations may progress to thoughts of, and plans for, suicide. It is important to ask about these ideas in every case (the assessment of suicidal risk is considered further in Chapter 16).

Feelings of guilt often take the form of unreasonable self-blame about minor matters—for example, the patient may feel guilty about past trivial acts of dishonesty or letting someone down. Usually these events have not been in the patient’s thoughts for years, but when he becomes depressed they flood back into his memory, accompanied by intense feelings. Preoccupations of this kind strongly suggest depressive disorder. Some patients have similar feelings of guilt but do not attach them to any particular event. Other memories are focused on unhappy events; the patient remembers occasions when he was sad, when he failed, or when his fortunes were at a low ebb. These gloomy memories become increasingly frequent as the depression deepens. The patient blames himself for his misery and incapacity, and attributes it to personal failing and moral weakness (a view not uncommonly held by the wider public).

Goal-directed behaviour

Lack of interest and enjoyment (also known as anhedonia) is frequent, although it is not always complained of spontaneously. The patient shows no enthusiasm for activities and hobbies that he would normally enjoy. He feels no zest for living and no pleasure in everyday things. He often withdraws from social encounters. Reduced energy is characteristic (although depression is sometimes associated with a degree of physical restlessness that can mislead the observer). The patient feels lethargic, finds everything an effort, and leaves tasks unfinished. For example, a normally house-proud person may leave the beds unmade and dirty plates on the table. Work outside the home becomes increasingly difficult. Understandably, many patients attribute this lack of energy to physical illness.

Psychomotor changes

Psychomotor retardation is frequent (although, as described later, some patients are agitated rather than slowed down). The retarded patient walks and acts slowly. Slowing of thought is reflected in their speech; there is a significant delay before questions are answered, and pauses in conversation may be unusually prolonged. Agitation is a state of restlessness that is experienced by the patient as inability to relax, and is seen by an observer as restless activity. When it is mild, the patient is seen to be plucking at his fingers and making restless movements of his legs; when it is severe, he cannot sit for long, and instead paces up and down.

Anxiety is frequent, although not invariably present, in severe depression. (As described later, it is common in less severe depressive disorders.) Another common symptom is irritability, which is the tendency to respond with undue annoyance to minor demands and frustrations.

Biological symptoms

There is an important group of symptoms that are often described as ‘biological’ (also referred to as ‘melancholic’, ‘somatic’ or ‘vegetative’). These symptoms include sleep disturbance, diurnal variation in mood, loss of appetite, loss of weight, constipation, loss of libido, and, among women, amen-orrhoea. They are very common in depressive disorders of severe degree (but less usual in mild depressive disorders). Some of these symptoms require further comment.

Sleep disturbance in depressive disorders is of several kinds. The most characteristic type is early-morning waking, but delay in falling asleep and waking during the night also occur. Early-morning waking occurs 2 or 3 hours before the patient’s usual time of waking. He does not fall asleep again, but lies awake feeling unrefreshed and often restless and agitated. He thinks about the coming day with pessimism, broods about past failures, and ponders gloomily about the future. It is this combination of early waking and depressive thinking that is important in diagnosis. It should be noted that some depressed patients sleep excessively rather than waking early, but they still report waking unrefreshed.

Weight loss in depressive disorders often seems to be greater than can be accounted for merely by the patient’s reported lack of appetite. In some patients the disturbances of eating and weight are towards excess—that is, they eat more than usual and gain weight. Usually eating brings temporary relief of their distressing feelings.

Complaints about physical symptoms are common in depressive disorders. They take many forms, but complaints of constipation, fatigue, and aching discomfort anywhere in the body are particularly common. Complaints about any pre-existing physical disorder usually increase, and hypochondriacal preoccupations are common.

Other features

Several other psychiatric symptoms may occur as part of a depressive disorder, and occasionally one of them dominates the clinical picture. They include depersonalization, obsessional symptoms, panic attacks, and dissociative symptoms such as fugue or loss of function of a limb. Complaints of poor memory are also common; depressed patients commonly show deficits on a wide range of neuropsychological tasks, but impairments in the retrieval and recognition of recently learned material are particularly prominent. Sometimes the impairment of memory in a depressed patient is so severe that the clinical presentation resembles that of dementia. This presentation, which is particularly common in the elderly, is sometimes called depressive pseudodementia (see p. 503).

Psychotic depression

As depressive disorders become increasingly severe, all of the features described above occur with greater intensity. There is complete loss of function in social and occupational spheres. Inattention to basic hygiene and nutrition may give rise to concern about the patient’s well-being. Psychomotor retardation may make interviewing difficult or impossible. In addition, there may be delusions and hallucinations, in which case the disorder is referred to as psychotic depression.

The delusions of severe depressive disorders are concerned with the same themes as the non-delusional thinking of moderate depressive disorders. Therefore they are termed mood congruent. These themes are worthlessness, guilt, ill health, and, more rarely, poverty. Such delusions have been described in Chapter 1, but a few examples may be helpful at this point. The patient with a delusion of guilt may believe that some dishonest act, such as a minor concealment when filling in a tax return, will be discovered and that he will be punished severely and humiliated. He is likely to believe that such punishment is deserved. A patient with hypochondriacal delusions may be convinced that he has cancer or venereal disease. A patient with a delusion of impoverishment may wrongly believe that he has lost all of his money in a business venture.

Persecutory delusions also occur. The patient may believe that other people are discussing him in a derogatory way or are about to take revenge on him. When persecutory delusions are part of a depressive syndrome, typically the patient accepts the supposed persecution as something that he has brought upon himself. In his view, he is ultimately to blame. This can be a useful diagnostic feature for distinguishing severe depression from non-affective psychosis (see Chapter 11). Some depressed patients experience delusions and hallucinations that are not clearly related to themes of depression (i.e. they are ‘mood-incongruent’). Their presence appears to worsen the prognosis of the illness.

Particularly severe depressive delusions are found in Cotard’s syndrome, which was described by the French psychiatrist, Jules Cotard, in 1882. The characteristic feature is an extreme kind of nihilistic delusion. For example, some patients may complain that their bowels have been destroyed, so they will never be able to pass faeces again. Others may assert that they are penniless and have no prospect of ever having any money again. Still others may be convinced that their whole family has ceased to exist and that they themselves are dead. Although the extreme nature of these symptoms is striking, such cases do not appear to differ in important ways from other severe depressive disorders.

Other clinical variants of depressive disorders

Agitated depression

This term is applied to depressive disorders in which agitation is prominent. As already noted, agitation occurs in many severe depressive disorders, but in agitated depression it is particularly severe. Agitated depression is seen more commonly among middle-aged and elderly patients than among younger individuals.

Retarded depression

This name is sometimes applied to depressive disorders in which psychomotor retardation is especially prominent. There is no evidence that they represent a separate syndrome, although the presence of prominent retardation is said to predict a good response to electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). If the term is used, it should be in a purely descriptive sense. In its most severe form, retarded depression merges with depressive stupor.

Depressive stupor

In severe depressive disorder, slowing of movement and poverty of speech may become so extreme that the patient is motionless and mute. Such depressive stupor is rarely seen now that active treatment is available. Therefore the description by Kraepelin (1921, p. 80) is of particular interest:

The patients lie mute in bed, give no answer of any sort, at most withdraw themselves timidly from approaches, but often do not defend themselves from pinpricks.… They sit helpless before their food; perhaps, however, they let themselves be spoon-fed without making any difficulty.

Kraepelin commented that recall of the events that took place during stupor was sometimes impaired when the patient recovered. Nowadays, the general view is that on recovery patients are able to recall nearly all of the events that took place during the period of stupor. It is possible that in some of Kraepelin’s cases there was clouding of consciousness (possibly related to inadequate fluid intake, which is common in these patients). Patients in states of depressive stupor may exhibit catatonic motor disturbances (see p. 24).

Atypical depression

The term atypical depression is generally applied to disorders of moderate clinical severity. The precise meaning of the term has varied over the years, but currently it is applied to disorders characterized by:

• variably depressed mood with mood reactivity to positive events

• overeating and oversleeping

• extreme fatigue and heaviness in the limbs (leaden paralysis)

• pronounced anxiety.

Many patients with these clinical symptoms have a lifelong tendency to react in an exaggerated way to perceived or real rejection (rejection sensitivity), although this character trait can be exacerbated by the presence of a depressive disorder. Patients with atypical depression also have an earlier onset of illness and a more chronic course. The importance of recognizing atypical depression is that, because of their interpersonal sensitivity, patients with this disorder can be hard to manage and may be regarded as having ‘difficult’ personalities rather than depressive disorder. Atypical depression also seems to be associated with a poor response to tricyclic antidepressant treatment but a better response to monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) and perhaps selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) (see Stewart et al., 2009).

Mild depressive states

It might be expected that mild depressive disorders would present with symptoms similar to those of the depressive disorders described above, but with less intensity. To some extent this is the case, but in mild depressive disorders there are frequently additional symptoms that are less prominent in severe disorders. These symptoms have been characterized in the past as ‘neurotic’, and they include anxiety, phobias, obsessional symptoms, and, less often, dissociative symptoms. In terms of classification, both DSM-IV and ICD-10 have categories of mild depression where criteria for a depressive episode are met but the depressive symptoms are fewer and less severe (see Table 10.1).

Apart from the ‘neurotic’ symptoms that are found in some cases, mild depressive disorders are characterized by the expected symptoms of low mood, lack of energy and interest, and irritability. There is sleep disturbance, but not the early-morning waking that is so characteristic of more severe depressive disorders. Instead, there is more often difficulty in falling asleep, and periods of waking during the night, usually followed by a period of sleep at the end of the night. ‘Biological’ features (poor appetite, weight loss, and low libido) are not usually found. Although mood may vary during the day, it is usually worse in the evening than in the morning. The patient may not appear obviously dejected, or slowed in their movement. Delusions and hallucinations are not present.

In their mildest forms, these cases merge into the minor mood disorders considered below. As described later, they pose considerable problems of classification. Many of these mild depressive disorders are brief, starting at a time of personal misfortune and subsiding when fortunes have changed or a new level of adjustment has been achieved. However, some cases persist for months or years, causing considerable suffering, even though the symptoms do not increase. These chronic depressive states are termed dysthymia. The term cyclothymic disorder refers to a persistent instability of mood in which there are numerous periods of mild elation or mild depression. It is seen as a milder variant of bipolar disorder. It is not unusual for episodes of more severe mood disorder to supervene in patients who experience dysthymia or cyclothymia, and the converse can also occur (Judd et al., 1998; Judd et al., 2002). This suggests that, in some individuals, milder symptoms are a limited expression of an underlying major mood disturbance.

Minor mood disorders

We have already seen that anxiety and depressive symptoms often occur together. Indeed, earlier writers considered that anxiety and depressive disorders could not be separated clearly even in patients who had been admitted to hospital with severe disorders. Although most psychiatrists now accept that the distinction can usually be made among the more severe forms that present in psychiatric practice, the distinction is less easy to make in the milder forms that present in primary care.

Classification

As psychiatrists have worked increasingly with general practitioners, the importance of minor anxiety–depressive disorders has been recognized, but without any agreement about classification.

ICD-10 includes a category of ‘mixed anxiety and depressive disorder’ which can be applied when neither anxiety symptoms nor depressive symptoms are severe enough to meet the criteria for an anxiety disorder or a depressive disorder, and when the symptoms do not have the close association with stressful events or significant life changes that is required for a diagnosis of acute stress reaction or adjustment disorder.

According to ICD-10, patients with this presentation are seen frequently in primary care, and there are many others in the general population who are not seen by doctors. In ICD-10 this diagnosis appears among the anxiety disorders, although some psychiatrists consider that the condition is more closely related to the mood disorders, a view that is reflected in the alternative term, minor affective disorder.

In DSM-IV, no comparable diagnosis appears in the classification. The appendix to the classification contains two provisional diagnoses that might be used for these cases, namely mixed anxiety and depressive disorder and minor depressive disorder. It is stated that there is insufficient factual information to justify the inclusion of either in the classification. Although little is known about these conditions or about their relationship to other disorders, patients commonly present to primary care doctors with this group of symptoms. A suitable category is needed even if it is not possible to write strict criteria for diagnosis.

Clinical picture

One of the best descriptions of minor affective disorder is that given by Goldberg et al. (1976), who studied 88 patients from a general practice in Philadelphia. The most frequent symptoms were:

• fatigue

• anxiety

• depression

• irritability

• poor concentration

• insomnia

• somatic symptoms and bodily preoccupation.

A very similar range of symptoms was found was found in the National Psychiatric Morbidity Household Survey (Jenkins et al., 1997), which surveyed the frequency of ‘neurotic’ symptomatology in a community sample.

Patients with minor affective disorders commonly present to medical practitioners with prominent somatic symptoms. The reason for this is uncertain; some symptoms are autonomic features of anxiety, and it is possible that patients expect somatic complaints to be viewed more sympathetically than emotional problems (see Chapter 15). Another point of clinical relevance is that minor affective disorders can be prolonged and in some cases may cause quite disabling difficulties in personal and occupational function. Thus the term ‘minor’ may not capture the serious consequences of the disorder for an individual. As noted above, in some patients minor affective disorders may represent a residual form of a major mood disturbance (Judd et al., 1998, 2002).

Mania

As already mentioned, the central features of the syndrome of mania are elevation of mood, increased activity, and self-important ideas.

Mood

When the mood is elevated, the patient appears cheerful and optimistic, and they may have a quality described by earlier writers as ‘infectious gaiety.’ However, other patients are irritable rather than euphoric, and this irritability can easily turn to anger. The mood often varies during the day, although not with the regular rhythm that is characteristic of many severe depressive disorders. In patients who are elated, it is not uncommon for high spirits to be interrupted by brief episodes of depression.

Appearance and behaviour

The patient’s appearance often reflects their prevailing mood. Their clothing may be brightly coloured and ill assorted. When the condition is more severe, the patient’s appearance is often untidy and dishevelled. Manic patients are overactive. Sometimes the persistent overactivity leads to physical exhaustion. Manic patients start many activities but leave them unfinished as new ones attract their attention. Appetite is increased, and food may be eaten greedily with little attention to conventional manners. Sexual desires are increased, and sexual behaviour may be uninhibited and quite out of character. Women may neglect precautions against pregnancy, a point that calls for particular attention if the patient is of childbearing age. Sleep is often reduced. Patients wake early, feeling lively and energetic, and often get up and busy themselves noisily, to the surprise (and sometimes annoyance) of other people.

Speech and thought

The speech of manic patients is often rapid and copious as thoughts crowd into their minds in quick succession. When the disorder is more severe, there is flight of ideas (see p. 23), with such rapid changes that it is difficult to follow the train of thought. However, the links are usually understandable if the speech can be recorded and reviewed. This is in contrast to thought disorder in schizophrenia, where changes in the flow of thought may not be comprehensible even on reflection.

Expansive ideas are common. Patients believe that their ideas are original, their opinions important, and their work of outstanding quality. Many patients become extravagant, spending more than they can afford (e.g. on expensive cars or jewelry). Others make reckless decisions to give up good jobs, or embark on plans for ill-considered and risky business ventures.

Sometimes these expansive themes are accompanied by grandiose delusions. Some patients may believe that they are religious prophets or destined to advise statesmen about major issues. At times there are delusions of persecution, when the patient believes that people are conspiring against them because of their special importance. Delusions of reference and passivity feelings also occur. Schneiderian first-rank symptoms (see Chapter 11, Table 11.3) have been reported in around 10–20% of manic patients. Neither the delusions nor the first-rank symptoms last for long, most of them disappearing or changing in content within a period of days.

Perceptual disturbances

Hallucinations occur. These are usually consistent with the mood, taking the form of voices speaking to the patient about his special powers or, occasionally, of visions with a religious content.

Other features

Insight is invariably impaired in more severe manic states. Patients see no reason why their grandiose plans should be restrained or their extravagant expenditure curtailed. They seldom think of themselves as ill or in need of treatment.

Most patients can exert some control over their symptoms for a short time, and many do so when the question of treatment is being assessed. For this reason it is important to obtain a history from an informant whenever possible. Henry Maudsley (1879, p. 398) expressed the problem well:

Just as it is with a person who is not too far gone in intoxication, so it is with a person who is not too far gone in acute mania; he may on occasion pull his scattered ideas together by an effort of will, stop his irrational doings and for a short time talk with an appearance of calmness and reasonableness that may well raise false hopes in inexperienced people.

The symptoms that are required to fulfil the criteria for ‘manic episode’ in DSM-IV are listed in Table 10.3. The criteria for manic episode in ICD-10 are very similar, although the number of manic symptoms required for diagnosis is not specified so precisely.

Table 10.3 Criteria for manic episode in DSM-IV

Hypomania refers to a state of elevated mood that is of lesser extent than mania. In DSM-IV, the criteria are similar to those for mania, with the following distinctions:

• The duration of elevated, expansive, or irritable mood need be only 4 days.

• The mood disturbance, although associated with an unequivocal change in function, is not sufficiently severe to cause marked impairment in social or occupational activities, or to necessitate hospital admission.

• Psychotic features are absent.

Mixed mood (affective) states

Depressive and manic symptoms sometimes occur at the same time. Patients who are overactive and over-talkative may be having profoundly depressive thoughts. In other patients, mania and depression follow each other in a sequence of rapid changes—for example, a manic patient may become intensely depressed for a few hours and then return quickly to his manic state. These changes were mentioned in early descriptions of mania by Griesinger (1867), and have been re-emphasized in recent years because they appear to predict a better response to certain mood stabilizers, such as valproate.

Rapid cycling disorders

Some bipolar disorders recur regularly with intervals of only days or weeks between episodes. In the nineteenth century these regularly recurring disorders were designated folie circulaire (circular insanity) by the French psychiatrist Jean-Pierre Falret (Falret, 1854). At present, the frequent recurrence of mood disturbance in bipolar patients is usually termed rapid cycling disorder. These recurrent episodes may be depressive, manic, or mixed. The main features are that recurrence is frequent (by convention at least four distinct episodes a year), and that episodes are separated by a period of remission or a switch to an episode of opposite polarity. A number of clinical features of rapid cycling disorder are important in management and prevention.

• They occur more frequently in women.

• Concomitant hypothyroidism is common.

• They can be triggered by antidepressant drug treatment.

• Lithium treatment as sole therapy is relatively ineffective.

The lifetime risk of rapid cycling in bipolar populations varies between studies, but is probably in the range 15–30%. Rapid cycling is often a rather temporary phenomenon, and in most patients it remits within about 2 years (Goodwin, 2009).

Manic stupor

In this unusual disorder, patients are mute and immobile. Their facial expression suggests elation, and on recovery they describe having experienced a rapid succession of thoughts typical of mania. The condition is rarely seen now that active treatment is available for mania. Therefore an earlier description by Kraepelin (1921, p. 106) is of interest:

The patients are usually quite inaccessible, do not trouble themselves about their surroundings, give no answer, or at most speak in a low voice … smile without recognizable cause, lie perfectly quiet in bed or tidy about at their clothes and bedclothes, decorate themselves in an extraordinary way, all this without any sign of outward excitement.

On recovery, patients can remember the events that occurred during their period of stupor. The condition may begin from a state of manic excitement, but at times it is a stage in the transition between depressive stupor and mania.

Transcultural factors

Mania appears to be present in all cultures. However, caution in diagnosis is needed, because culture-specific means of expressing distress can lead to behaviours that may be misdiagnosed as mania (Kirmayer and Groleau, 2001). There are cultural variations in the clinical presentation of depressive states, but in most countries depression appears to be under-diagnosed, particularly in primary care. Although somatic features are undoubtedly found in all societies, they are more frequent and prominent in non-Western cultures. However, it is necessary to distinguish between somatization (see Chapter 15) and somatic metaphors for an emotional state. For examples, Punjabi women living in London have been found to use expressions such as ‘weight on my heart’ and ‘feelings of heat’ to express emotional suffering, the presence of which they were well aware. It should also be noted that sadness, joylessness, anxiety, and lack of energy are common symptoms of depression in all cultures (for a review, see Bhugra and Mastrogianni, 2004).

Classification of mood disorders

The fundamental clinical distinction in the classification of mood disorders is between depression and mania. Depressive episodes have been subdivided in various ways, which are outlined below, but the results of much of this work have not been particularly useful. However, studies of the longitudinal course of mood disorders have indicated that there are useful clinical distinctions to be made between people who never experience mania or hypomania (recurrent depressive disorder) and those who do (bipolar disorder).

Classification of depression

There is no general agreement about the best method of classifying depressive disorders. A number of approaches have been tried, based on the following:

• presumed aetiology

• symptomatic picture

• course.

Classification by presumed aetiology

Historically, depressive disorders were sometimes classified into two kinds—those in which the symptoms were caused by factors within the individual, and were independent of outside factors (endogenous depression), and those in which the symptoms were a response to external stressors (reactive depression). However, it has been recognized for many years that this distinction is unsatisfactory. For example, Lewis (1934) wrote:

every illness is a product of two factors—of the environment working on the organism—whether the constitutional factor is the determining influence or the environmental one … is never a question to be dealt with as either/or.

As noted in Chapter 5, when considering the aetiology of individual cases of depression, the relative contributions of a variety of aetiological factors must be considered. Neither ICD-10 nor DSM-IV contains categories of reactive or endogenous depression.

Classification by symptomatic picture

Melancholic depression. It is well recognized that episodes of depression vary in symptomatic profile both within and between subjects. In the section on clinical description (see p. 207) it was noted that some depressive conditions are characterized by ‘biological’ symptoms, such as loss of appetite, psychomotor changes, weight loss, constipation, reduced libido, amenorrhoea, and early-morning waking. These symptoms have sometime been termed melancholic, and they have been used to delineate a specific subgroup of depressive disorders, namely major depression with melancholia in DSM-IV, or depressive episode with somatic symptoms in ICD-10 (see Table 10.4). The difficulty with this classification is that most patients have melancholic symptoms of some kind, though a careful search may be required to reveal them. Therefore the number of symptoms that are needed to fulfil the criterion for depression with melancholia is somewhat arbitrary. Despite this caveat, it is generally agreed that clear-cut melancholic depression is associated with the following clinical correlates (see Coryell, 2007):

• more severe symptomatology

• family history of depression

• poor response to placebo medication

• more evidence of neurobiological abnormalities (e.g. decreased latency to rapid eye movement sleep, cortisol hypersecretion).

Table 10.4 Clinical features of melancholic and somatic depression

Melancholic features (DSM-IV) |

Loss of interest or pleasure in usual activities* |

Lack of reactivity to pleasurable stimuli,* plus at least three of the following: • Distinct quality of mood (unlike normal sadness) • Morning worsening of mood* • Early-morning waking* • Psychomotor agitation or retardation* • Significant anorexia or weight loss* • Excessive guilt • Marked loss of libido* (ICD-10 only) |

* Somatic symptoms of depression in ICD-10 (at least four are required for diagnosis).

It is still not clear whether melancholic depression is a distinct subtype, or whether it represents a point on a continuum of severity, towards the more severe end. Kendler (1997) attempted to answer this question using a population sample of twins. He found evidence that melancholic depression did represent a valid subtype in that it identified a group of individuals with a particularly high familial risk of depression. However, the diagnosis of melancholia indicated the presence of a quantitatively more severe form of depression, rather than a distinct aetiological subtype.

Psychotic depression. As noted above, severe depression can also be manifested with psychotic features (although in depressive psychosis the features of melancholia are almost invariably present as well). The presence of psychotic features indicates that treatment with antidepressant medication alone is unlikely to be successful, and that combination with antipsychotic drugs is usually needed (Anderson et al., 2008).

Non-melancholic depression. In this classification by symptom profile, the remaining forms of major depression (‘non-melancholic’ depression) include several different kinds of clinical disorder—for example, mild depressive episodes, atypical depression, and dysthymia. These depressions are more likely to have a relative prominence of features such as anxiety, hostility, phobias, and obsessional symptoms. In the past, because of these symptoms, non-melancholic depressions were sometimes called ‘neurotic depression’, but this term does not appear in current diagnostic classifications. As noted above (see p. 209), atypical depression has particular clinical characteristics and response to treatment; it therefore appears to merit a specific category within the non-melancholic depressions (Stewart et al., 2009).

Classification by course

Unipolar and bipolar disorders. Mood disorders are characteristically recurrent, and Kraepelin was guided by the course of illness when he brought mania and depression together as a single entity. He found that the course was essentially the same whether the original disorder was manic or depressive, and so he put the two together in a single category of manic–depressive psychosis.

This view was widely accepted until 1962, when Leonhard and colleagues suggested a division into three groups:

• patients who had had a depressive disorder only (unipolar depression)

• those who had had mania only (unipolar mania)

• those who had had both depressive disorder and mania (bipolar).

Nowadays, it is the usual practice not to use the term ‘unipolar mania’, but to include all cases of mania in the bipolar group on the grounds that nearly all patients who have mania eventually experience a depressive disorder.

In support of the distinction between unipolar and bipolar disorders, Leonhard et al. (1962) described differences in heredity between the groups, which have been confirmed by later studies (see p. 220). The question of whether or not unipolar and bipolar depression show important differences in their clinical presentation is controversial. Epidemiological studies suggest that depression with a bipolar course is associated more with psychotic features, diurnal mood variation, and hyper-somnia (Forty et al., 2008). However, the differences are not great. There must be some overlap between the two groups, because a patient who is classified as having unipolar depression at one time may have a manic disorder subsequently. In other words, the unipolar group inevitably contains some bipolar cases that have not yet declared themselves. Despite this limitation, the division into unipolar and bipolar cases is a useful classification because it has implications for treatment (see p. 252).

The ability to predict which patients who present with depression will eventually develop bipolar illness is currently limited. The presence of any hypomanic or mixed symptomatology at initial presentation has some predictive value, but the majority of depressed patients who convert to bipolar illness do not have hypomanic symptoms during the initial episodes of depression. Other clinical features associated with subsequent development of bipolar illness include early age of onset and clinical severity, particularly the presence of psychosis (see Fiedorowicz et al., 2011).

Seasonal affective disorder. Some patients repeatedly develop a depressive disorder at the same time of year, usually the autumn or winter. In some cases the timing reflects extra demands placed on the person at a particular season of the year, either in work or in other aspects of their life. In other cases there is no such cause, and it has been suggested that seasonal affective disorder is related in some way to the changes in the seasons (e.g. to the number of hours of daylight). Although these seasonal affective disorders are characterized mainly by the time at which they occur, some symptoms are said to occur more often than in other mood disorders. These symptoms include:

• hypersomnia

• increased appetite, with craving for carbohydrate

• an afternoon slump in energy levels.

The most common pattern is onset in autumn or winter, and recovery in spring or summer. This condition is also called ‘winter depression.’ Some patients show evidence of hypomania or mania in the summer, which suggests that they have a seasonal bipolar illness. This pattern has led to the suggestion that shortening of daylight hours is important in the pathophysiology of winter depression, and treatment methods include exposure to bright artificial light during hours of darkness. For a review, see Eagles (2004). The use of bright light treatment is reviewed on p. 564.

Brief recurrent depression. Some individuals experience recurrent depressive episodes of short duration, typically 2 to 7 days, that are not of sufficient duration to meet the criteria for major depression or depressive episode. These episodes recur with some frequency, about once a month on average. There is no apparent link with the menstrual cycle in female sufferers. Although the depressive episodes are short, they are as severe as the more enduring depressive disorders, and can be associated with suicidal behaviour. Thus recurrent brief depression is associated with much personal distress and social and occupational impairment. There appears to be little comorbidity with manic illness or dysthymia. Individuals with recurrent brief depression often receive treatment with antidepressant medication, but its value is questionable (Pezawas et al., 2005).

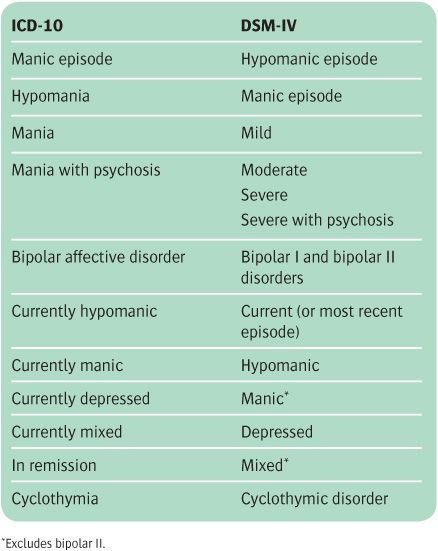

Classification in DSM and ICD

The main categories in the sections on mood disorders in DSM-IV and ICD-10 are shown in Tables 10.4 and 10.5. Broad similarities are evident, together with some differences. The first similarity is that both systems contain categories for single episodes of mood disorder as well as categories for recurrent episodes. The second is that both recognize mild but persistent mood disturbances in which there is either a repeated alternation of high and low mood (cyclothymia) or a sustained depression of mood (dysthymia). In neither case are the mood disturbances sufficiently severe to meet the criteria for a hypo-manic or depressive episode. In DSM-IV, mood disorders that are judged to be secondary to a medical condition are included as a subcategory of mood disorders, whereas in ICD-10 these conditions are classified as mood disorders under ‘Organic mental disorders.’

Bipolar disorder

Both classifications delineate hypomania from mania on the basis of duration of symptoms, absence of psychotic features, and lesser degree of social and occupational impairment. A manic episode can be further subdivided according to severity and whether or not psychotic symptoms are present. In DSM-IV, the presence of a single episode of hypomania or mania is sufficient to meet the criteria for bipolar affective disorder. In ICD-10, however, at least two episodes of mood disturbance are needed for this diagnosis. DSM-IV also categorizes bipolar disorder as follows:

• bipolar I (in which mania has occurred on least one occasion)

• bipolar II (in which hypomania has occurred, but mania has not).

The diagnosis of bipolar II disorder is intended to indicate the importance of detecting mild hypomanic episodes in patients who might otherwise be diagnosed as having recurrent major depression. The presence of such episodes may have implications for treatment response. In DSM-IV, if a hypomanic or manic episode appears to have been precipitated by a somatic treatment (e.g. antidepressant drug therapy), it is not counted towards the diagnosis of bipolar I or bipolar II disorder, although there is a growing body of opinion that antidepressant-induced mania or hypomania should be considered to indicate an underlying bipolar disorder (Goodwin, 2009).

Table 10.5 Classification of bipolar disorder

Bipolar spectrum disorders. There is debate about where the line should be drawn between unipolar depression and bipolar disorder, because some patients with definite depressive episodes appear to have features of bipolarity but do not meet the DSM-IV criteria for mania or hypo-mania. Such patients may, for example, have elevations of mood that last for less than the required 4 days, or that have little discernible effect on functioning. In DSM-IV, the diagnosis of bipolar disorder ‘not otherwise specified’ can be applied in this situation. The term bipolar spectrum is also used. The treatment of bipolar depression differs to some extent from that given to patients with recurrent unipolar depression (see below), so making the diagnostic distinction between unipolar and bipolar depression can have important implications for management. However, it is not clear whether depressed patients in the bipolar spectrum do better when treated as having bipolar depression rather than unipolar depression (for a discussion, see Goodwin, 2009).

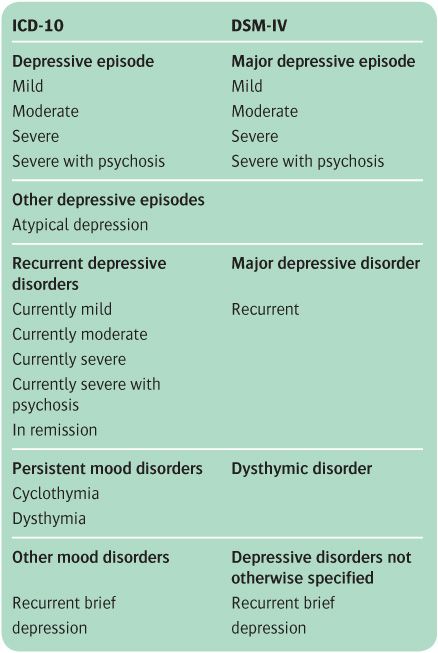

Depressive disorders

Both ICD-10 and DSM-IV classify depressive episodes on the basis of severity and whether or not psychotic features are present. It is also possible to specify whether the depressive episode has melancholic (DSM-IV) or somatic (ICD-10) features. In DSM-IV, an episode of major depression with appropriate clinical symptomatology (see above) can be specified as atypical depression. In ICD-10, atypical depression is classified separately under ‘Other depressive episodes.’ Both ICD-10 and DSM-IV allow the diagnosis of recurrent brief depression, but under slightly different headings (see Table 10.6).

Table 10.6 Classification of depressive disorders

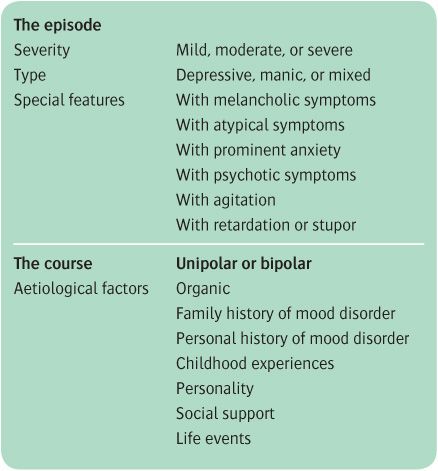

Classification and description in everyday practice

Although neither DSM-IV nor ICD-10 is entirely satisfactory, it seems unlikely that further re-arrangement of descriptive categories would be an improvement. A solution will only be achieved when we have a better understanding of aetiology. Meanwhile, either ICD-10 or DSM-IV should be used for statistical returns. For most clinical purposes, it is better to describe disorders systematically than to classify them.

This can be done for every case by referring to the severity, the type of episode, the distinguishing symptomatic features, and the course of the disorder, together with an evaluation of the relative importance of known aetiological factors (see Table 10.7). It has become conventional practice to record all cases with a manic episode as bipolar, even if there has been no depressive disorder, on the grounds that most manic patients develop a depressive disorder eventually, and in several important respects manic patients resemble patients who have had both types of episode. This convention is followed in this textbook.

Table 10.7 A systematic scheme for the clinical description of mood disorders

Differential diagnosis

Depressive disorder

Depressive disorders have to be distinguished from the following:

• normal sadness

• anxiety disorders

• schizophrenia

• organic brain syndromes.

As already explained on p. 205, the distinction from normal sadness is made on the basis of the presence of other symptoms of the syndrome of depressive disorder. Depressive disorders also have rates of comorbidity with a wide range of other disorders—for example, anxiety disorders, eating disorders, substance misuse, and personality disorder. In all of these cases it is important to recognize and treat the depressive disorder.

Anxiety disorders

Mild depressive disorders are sometimes difficult to distinguish from anxiety disorders. Accurate diagnosis depends on assessment of the relative severity of anxiety and depressive symptoms, and on the order in which they appeared. Similar problems arise when there are prominent phobic or obsessional symptoms, or when there are dissociative symptoms with or without histrionic behaviour. In all of these cases, the clinician may fail to identify the depressive symptoms and so prescribe the wrong treatment.

Schizophrenia

The distinction from schizophrenia can be most difficult. Auditory hallucinations and delusions, including some that are characteristic of schizophrenia, such as delusions of reference, can occur in manic disorders. However, these symptoms usually change quickly in terms of content, and seldom outlast the phase of overactivity. When there is a more or less equal mixture of features of the two syndromes, the term schizoaffective is often used. This term is discussed further in Chapter 11. Further clues to diagnosis can often be elicited by a careful personal and family psychiatric history.

Dementia and other organic conditions

In middle and late life, depressive disorders are sometimes difficult to distinguish from dementia, because some patients with depressive symptoms complain of considerable difficulty in remembering. In fact, patients with severe depression can perform very badly on tests of cognitive function, and distinction between the two conditions purely in terms of the nature of the cognitive impairment may not be possible. Here the presence of depressive symptoms is the key to diagnosis, which should be confirmed with improvement of the memory disorder as normal mood is restored. Numerous other general medical conditions can present with depressive features (see p. 384). The key to diagnosis is a careful history and physical examination, supplemented by special investigations where appropriate.

Mania

Manic disorders have to be distinguished from the following:

• schizophrenia

• organic brain disease involving the frontal lobes (including brain tumour and HIV infection)

• states of brief excitement induced by amphetamines and other illegal drugs.

Schizophrenia

The distinction from schizophrenia depends on a careful search for the characteristic features of this condition (see Chapter 11). Difficult diagnostic problems may arise when the patient has depressive psychosis, but here again the distinction can usually be made on the basis of a careful examination of the mental state, and of the order in which the symptoms appeared. Information about the past psychiatric history may also be useful. Particular difficulties also arise when symptoms characteristic of depressive disorder and of schizophrenia are found in equal measure in the same patient; these so-called schizoaffective disorders are discussed on p. 266.

Organic brain disorder and drug misuse

An organic brain lesion should always be considered, especially in middle-aged or older patients with expansive behaviour and no past history of affective disorder. In the absence of gross mood disorder, extreme social disinhibition (e.g. urinating in public) strongly suggests frontal lobe pathology. In such cases, appropriate neurological investigation is essential. In younger adults, infection with HIV or head injury may lead to the manifestation of mania.

The distinction between mania and excited behaviour due to drug misuse depends on the history, and on an examination of the urine for drugs, which is needed before treatment with psychotropic drugs is started. Drug-induced states usually subside quickly once the patient is in hospital (see Chapter 17). However, it should be remembered that a significant proportion of patients who have bipolar disorder misuse alcohol and other drugs.

The epidemiology of mood disorders

It is difficult to determine the prevalence of depressive disorder, partly because different investigators have used different diagnostic definitions. More modern investigations have used structured diagnostic interviews linked to standardized diagnostic criteria such as the Diagnostic Interview Schedule (DIS) and the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) (see p. 65). Of all the mood disorders, bipolar cases are probably identified more reliably because mania is somewhat easier to define and diagnose.

Bipolar disorder

More recent community surveys in industrialized countries have suggested that:

• the lifetime risk for bipolar disorder is in the range 0.3–1.5%

• the 6-month prevalence of bipolar disorder is not much less than the lifetime prevalence, indicating the chronic nature of the disorder

• the prevalence in men and women is the same

• the mean age of onset is about 17 years in community studies

• bipolar disorder is highly comorbid with other disorders, particularly anxiety disorders and substance misuse.

Depression

Defining the boundaries of depressive episodes in community surveys presents a number of difficulties. However, if the DSM-IV criteria for major depression are applied, recent surveys in industrialized countries suggest that:

• the 12-month prevalence of major depression in the community is around 2–5%

• the lifetime rates in different studies vary considerably (in the range 4–30%). The true figure probably lies in the range 10–20%

• the mean age of onset is about 27 years

• rates of major depression are about twice as high in women as in men, across different cultures

• there may be increased rates of depression in people born since 1945

• rates of depression are higher in the unemployed and divorced

• major depression has a high comorbidity with other disorders, particularly anxiety disorders and substance misuse.

The reasons for higher rates of major depression among women are uncertain. This increase starts to become apparent at puberty, and could be due in part to a greater readiness of women to admit to having depressive symptoms. However, such selective reporting is unlikely to be the whole explanation. It is possible that some depressed men misuse alcohol and are diagnosed as suffering from alcohol-related disorders rather than depression, with the consequence that the true number of major depressive disorders is underestimated (Branney and White, 2008). Again, misdiagnosis of this kind is unlikely to account for the whole of the difference. The possibility that gender-related differences in neurobiology (e.g. the organization of central 5-HT pathways) might underlie differences in susceptibility to depression requires further investigation. Furthermore, in many societies women are subject to various kinds of social disadvantage and, for example, are more likely than men to experience sexual abuse and domestic violence. Factors of this sort are also likely to be implicated in their increased risk of depression.

Although it used to be thought that the risk of depressive disorders increased with age, recent surveys suggest that major depression is most prevalent in the 18–44 years age group. A number of studies have suggested that people born since 1945 in industrialized countries have both a higher lifetime risk of major depression and an earlier age of onset. These studies have mainly been retrospective, and it is possible that the apparent increased rate of major depression in young people is due to the fact that older people forget (or are less willing to reveal) that they have been depressed. For a review of the epidemiology of mood disorders, see Joyce (2009).

Dysthymia and recurrent brief depression

The lifetime risk for dysthymia is around 4% (Alonso et al., 2004). Rates of dysthymia are higher in women and in the divorced. There is less epidemiological information about recurrent brief depression, but in the Zurich prospective study the 12-month prevalence for recurrent brief depression was about 2.6%, very similar to the rate found for dysthmia (2.3%) (Pezawas et al., 2003).

Minor mood disorders

Estimates of the frequency of minor mood disorders show wide variations because the different studies have not defined cases in the same way. However, these are probably the most prevalent psychiatric disorders in the community. For example, in the National Psychiatric Morbidity Household Survey (Jenkins et al., 1997), the overall 1-week prevalence of neurotic disorder was 16% (12.3% in males and 19.5% in females). Nearly half of this group met the ICD-10 criteria for mixed anxiety and depression. Similar findings were obtained in the Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey in England, |in which McManus et al. (2007) found that mixed anxiety and depression was the most common mental disorder in the community, with a 1-week prevalence of 9%.

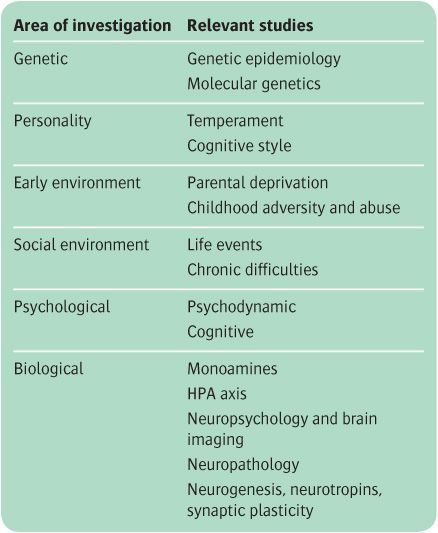

The aetiology of mood disorders

There have been many different approaches to the aetiology of mood disorders. There is substantial knowledge about the genetic epidemiology of depression and bipolar disorder, and how certain childhood experiences can lay down a predisposition to mood disorders in adulthood. There is also a good understanding of the role of current life difficulties and stresses in provoking mood disorders in predisposed individuals. There is much less knowledge about the mechanism involved in the translation of these predisposing and provoking factors into clinical symptomatology.

When trying to elucidate these mechanisms (which, of course, have important implications for treatment), investigators have employed two main conceptual approaches, which can be broadly termed psychological and biological. It is likely, of course, that these approaches represent different levels of enquiry that will eventually inform each other. The main kinds of investigations that will be discussed are listed in Table 10.8. In most research areas there are many more data available concerning the aetiology of depression than on that of mania. The aetiology section in the current chapter is structured so as to illustrate to the reader the many ways in which research into the causation of psychiatric disorder can be approached (see Box 10.1). It may therefore be helpful for this section to be read in conjunction with Chapter 5.

Genetic causes

Family and twin studies

Familial aggregation

The risk of mood disorders is increased in first-degree relatives of both bipolar and unipolar probands, with the risk being about twice as great in relatives of bipolar patients (see Table 10.9). Relatives of bipolar probands have increased risks of unipolar depression and schizoaffective disorder as well as bipolar disorder. By contrast, relatives of patients with unipolar depression do not have increased rates of bipolar disorder or schizoaffective disorder.

Table 10.8 The aetiology of mood disorders

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree