▪ HYPOKINETIC DISORDERS

Hypokinetic disorders, which are also known as akinetic-rigid syndromes, cause considerable disability because of decreased or slowed spontaneous movement, also known as hypokinesia or bradykinesia, rigidity, and postural instability. Tremor is commonly associated with akinesia and rigidity and is discussed separately later. The most common cause of these signs is idiopathic Parkinson’s disease, but they also occur in other forms of parkinsonism, including drug-induced parkinsonism, vascular parkinsonism, and a group of neurodegenerative disorders collectively referred to as atypical parkinsonism when they are commonly accompanied by other neurological signs.

Idiopathic Parkinson’s Disease

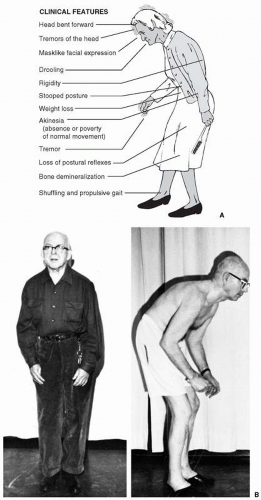

Idiopathic Parkinson’s disease (PD) is the most common of the akinetic-rigid syndromes, presents in middle to late life, and affects approximately 0.3% of the entire population of industrialized countries and 1% of all persons over the age of 60 years. The diagnosis of clinically probable PD requires the presence of at least two of the cardinal features of the disease—resting or postural tremor, rigidity, and bradykinesia. Patients often initially present with complaints of tremor, usually accompanied by unilateral or asymmetrical clumsiness and slowness of one hand and sometimes the leg on the same side, best demonstrated during finger- or foot-tapping maneuvers. Other features typically seen in parkinsonism include reduced voice volume or facial expression that are frequently mistaken for depression, a stare with reduced eye-blink frequency, slowing in routine activities of daily living, hesitation arising from deep chairs, flexed posture, and shuffling gait (

Fig. 13.1A). As the disease progresses, signs of akinesia and postural disturbance predominate. Progressive mutism, dysphagia, severe gait disturbance, freezing, and falls resulting from loss of postural reflexes may eventually produce severe disability. A particularly severe form of

flexed posture of the trunk and upper limbs often associated with more advanced PD is shown in

Figure 13.1B.

In addition to the prominent motor disability in PD, there are significant nonmotor manifestations as well, including a high rate of psychiatric comorbidity, such as depression, anxiety, and cognitive dysfunction ranging from mild impairment to dementia. Depression is the most common neuropsychological condition affecting patients with PD and may in fact precede motor symptoms of PD by several years. Although only approximately 5% of patients with PD meet criteria for moderate to severe depression, 45% to 50% of patients with PD meet criteria for mild depression. Anxiety disorders are considerably less common but also can be an important comorbidity, especially in patients who experience significant motor fluctuations. Obsessions and compulsions are a potentially devastating complication of antiparkinson medication, specifically dopamine agonists such as pramipexole and ropinirole. Reports of dopamine agonist-induced pathological gambling, hypersexuality, eating and shopping compulsions, and punding (a stereotyped behavior characterized by repetitive handling of mechanical objects), have all led to greater scrutiny and surveillance while caring for patients with PD on these drugs. Psychosis in the form of visual hallucinations is also commonly triggered by antiparkinson medication but when present spontaneously may signal the presence of dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB), with its distinctive visuospatial impairments and burden of microscopic PD pathology in the visual cortex. The distinction from PD-related dementia (PDD) is controversial; however, typically its diagnosis is made when time of onset of cognitive symptoms occurs within a year of developing motor symptoms of PD.

The motor symptoms and signs of PD arise from dysfunction in the basal ganglia, which include the substantia nigra pars compacta and pars reticulata, subthalamic nucleus, thalamus, caudate nucleus, putamen, and globus pallidus. Collectively, this group of structures is thought to be responsible for the automatic execution of learned motor plans. The hallmark pathological finding in the brains of patients with PD is degeneration of dopaminergic neurons projecting from the substantia nigra to the striatum, consisting of the caudate and putamen. Lewy bodies, which are eosinophilic intracytoplasmic neuronal inclusions containing insoluble proteins, are found in areas of neuronal degeneration, particularly in the substantia nigra. Protein aggregation in the form of alpha-synuclein is thought to be possibly neurotoxic and to play a presently unclear role in neurodegeneration. Dopamine is released from the axon terminals of substantia nigra pars compacta neurons in the striatum on two populations of striatal neurons, which initiate neurotransmission through a direct and an indirect pathway through the globus pallidus, both of which facilitate striatum-pallidal-thalamocortical interactions in the control of movement. As a result of degeneration of nigral dopaminergic neurons, projections from the substantia nigra to the striatum are reduced in PD. As a result, the indirect pathway is disinhibited and the direct pathway is inhibited, both leading to enhanced pallidal-thalamic inhibition followed by reduced thalamocortical facilitation. The net functional effect of this cascade is inhibition of motor function. Pathological changes are also found in other areas of the brain, including the brainstem, cortex, and autonomic ganglia. These changes result in noradrenergic, serotonergic, and cholinergic depletion with corresponding symptoms, including autonomic dysfunction, depression, and dementia. The early appearance and predominance of the latter in some cases results in the related disorder DLB.

Dopaminergic therapy has been the mainstay of medical treatment of PD. Treatment options consist of dopamine replacement with levodopa, dopamine agonists, and inhibition of dopamine metabolism (

Table 13.2). However, nonmotor aspects of PD, including depression, anxiety, sleep disorders, urinary incontinence, constipation, orthostatic hypotension, psychosis, and visual hallucinations are managed with medications that are used for these conditions in other disorders. One important exception lies in the use of neuroleptics for psychosis, because patients with PD who are given D2-receptor blockers are exquisitely sensitive to these medications and experience a profound worsening of motor function. Acceptable alternatives include quetiapine

and clozapine, which are relatively weak dopamine-receptor blockers. In patients with advanced PD, motor fluctuations to levodopa treatment and levodopa-induced dyskinesias may become prominently disabling, even with best medical therapy. Deep brain stimulation (DBS) of the subthalamic nucleus is often beneficial in relieving cardinal motor symptoms, reducing motor fluctuations, and reducing dyskinesias by reducing the need for levodopa.

The prognosis of PD is quite variable because of variable rates of progression in individual patients. Generally speaking, patients with PD are able to enjoy symptomatic motor benefit from oral medications for many years and later from DBS surgery. Mortality in PD depends on degree of motor dysfunction, as well as other comorbidities, but patients generally continue to have a favorable response to medical or surgical therapy 10 to 20 years after symptom onset. Efforts are currently underway to identify agents capable of slowing down or halting the neurodegenerative process.

Atypical Parkinsonism

In addition to the presence of akinesia, rigidity, and postural disturbance, there are a number of clinical features that, when present, may signify atypical parkinsonism (

Table 13.3). This is particularly true if symmetrical and midline motor manifestations appear early in the clinical course. Useful clues that may suggest other forms of parkinsonism are the presence of pyramidal tract signs, cerebellar ataxia, nystagmus, oculomotor abnormalities, early and severe dementia, frontal release signs, sensory findings, or prominent autonomic disturbances early in the illness.

Multiple System Atrophy

Parkinsonian syndromes resulting from multiple system atrophy (MSA) are typically the most difficult to distinguish on clinical grounds from idiopathic Parkinson’s disease. MSA is a group of disorders that share similar underlying neuropathology but exhibit a spectrum of variable and evolving neurological findings that differ depending on when the patient is seen in the course of the disease. For example, MSA-P may resemble idiopathic PD but is typically more rapidly progressive and only transiently or poorly responsive to levodopa. MSA-C features cerebellar ataxia early in the course, followed by varying degrees of parkinsonism. MSA-A features prominent orthostatic hypotension and bladder dysfunction. Although MSA also produces multiple sites of nervous system involvement, dementia is notably absent. Pyramidal tract findings, including hyperreflexia and the Babinski sign, may be present in any of the subtypes.

The pathophysiology of MSA is similar to that of PD in that alpha-synuclein is found in regions of neuronal loss and gliosis, earning its classification as a synucleinopathy. However, in contrast to PD, alpha-synuclein-containing Lewy bodies are not present and neurodegeneration involves loss of striatal neurons rather than nigral neurons. Glial cytoplasmic inclusions are found in dying neurons. Other areas involved may include the pontine and olivary nuclei in the cerebellar-predominant form of MSA, autonomic ganglia, and intermediolateral cell column of the spinal cord in patients with MSA with severe autonomic dysfunction.

Management with antiparkinson medications is often tried, with temporary and limited success. Approximately 30% of patients with MSA may be levodopa-responsive for several years before demonstrating the more typical lack of levodopa-responsiveness that characterizes most forms of atypical parkinsonism. Progressive autonomic dysfunction, motor disability, and predisposition to aspiration pneumonia are main causes of death. The average time from diagnosis to death is 9 to 10 years.

Progressive Supranuclear Palsy

Progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) is best known for paralysis of voluntary vertical and horizontal gaze, although the ocular findings do not necessarily appear early in the course of the illness. The oculomotor nuclei are preserved, and this gaze impairment can be overcome by oculocephalic head maneuvers that produce normal reflex eye movements. Initial eye findings may be subtle and limited to impaired saccadic movements. Supranuclear gaze palsy predominantly impairs downward more than upward gaze, but also affects horizontal gaze. Other eye findings may include blepharospasm, impaired voluntary eyelid opening, and square-wave jerks. Unlike in PD, postural instability and falls are the most common initial symptoms in PSP. Other early symptoms include generalized slowing, visual complaints, sleep disturbance, and personality change. Besides postural instability, other features that may distinguish PSP from PD include prominent axial rigidity and pseudobulbar palsy with spastic dysarthria, dysphagia, and emotional release. Cognitive decline is typically frontal in type, and it has been proposed that a frontal assessment battery test may distinguish PSP from other forms of parkinsonism. There is often a characteristic, astonished-appearing facial expression produced by the prominent stare, upper eyelid retraction, frontalis creases, and impaired voluntary gaze that is considerably different from the facial masking of PD.

PSP is characterized histologically by the presence of neurofibrillary tangles, consisting of aggregated tau microtubule-associated proteins, which are similar to those found in Alzheimer’s disease, corticobasal ganglionic degeneration, and Down’s syndrome. Neuronal death and gliosis are found prominently in substantia nigra, subthalamic nuclei, and brainstem nuclei, along with cortical atrophy. Management is largely supportive, because lack of levodopa-responsiveness is usually the rule, particularly with respect to early falls. Amantadine, which has dopaminergic and antiglutamatergic properties, has been shown in small, uncontrolled clinical trials to confer some benefit. Although cholinergic deficits are quite prominent in PSP, treatment with cholinesterase inhibitors has not offered any benefit in the cognitive domain. Nonpharmacological treatment largely consists of supportive care for swallowing dysfunction and lack of mobility. Death occurs at an average of 5 to 10 years from diagnosis.

Other Forms of Parkinsonism

Other causes of secondary parkinsonism include exposure to dopamine-depleters, dopamine-receptor blockers such as neuroleptics or metoclopramide, cerebrovascular disease with multiple small deep infarcts, anoxic encephalopathy, normal pressure hydrocephalus, head trauma, brain tumor, arteriovenous malformation, postencephalitic parkinsonism, and acquired hepatocerebral degeneration. Of these etiologies, of particular importance to the psychiatrist is that of neuroleptic-induced parkinsonism, which may occur with both typical and atypical newer

generation antipsychotics. Parkinsonism from these drugs is typically reversible with removal of the offending agent, but may take up to several months to occur.

Depending on the distribution of pathology, acquired brain disorders that cause parkinsonism are usually associated with dementia, corticospinal tract findings, pseudobulbar palsy, or gait ataxia. Dementia early in the clinical course is a useful clue that one is dealing with secondary parkinsonism. Parkinsonism may occur in association with a number of other primary, degenerative neurological disorders, such as familial olivopontocerebellar atrophy, Huntington’s disease, pallidal degenerations, corticobasal ganglionic degeneration, Alzheimer’s disease, Pick’s disease, basal ganglia calcification, Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, Wilson’s disease, and several metabolic and storage diseases of the nervous system. Wilson’s disease, which is reviewed later, is an especially important diagnostic consideration because neurological signs are often reversible with proper treatment. Differentiation of these secondary disorders from idiopathic PD is usually assisted by the rest of the neurological history and examination, supplemented in many cases by laboratory and imaging studies.