Clinical Evaluation of Patients

Progressive Supranuclear Palsy

Dentatorubral-Pallidoluysian Atrophy

Isolated Generalized Torsion Dystonia

Paroxysmal Nonkinesigenic Dyskinesia

Paroxysmal Kinesigenic Choreoathetosis

Paroxysmal Exercise-Induced Dyskinesias

Drug-Induced Movement Disorders

Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome

Other Drug-Induced Movement Disorders

Gilles de la Tourette Syndrome

Acquired Hepatocerebral Degeneration

Movement disorders (sometimes called extrapyramidal disorders) impair the regulation of voluntary motor activity without directly affecting strength, sensation, or cerebellar function. They include hyperkinetic disorders associated with abnormal, involuntary movements and hypokinetic disorders characterized by poverty of movement. Movement disorders result from dysfunction of deep subcortical gray matter structures termed the basal ganglia. Although there is no universally accepted anatomic definition of the basal ganglia, for clinical purposes they may be considered to comprise the caudate nucleus, putamen, globus pallidus, subthalamic nucleus, and substantia nigra. The putamen and the globus pallidus are collectively termed the lentiform nucleus; the combination of lentiform nucleus and caudate nucleus is designated the corpus striatum.

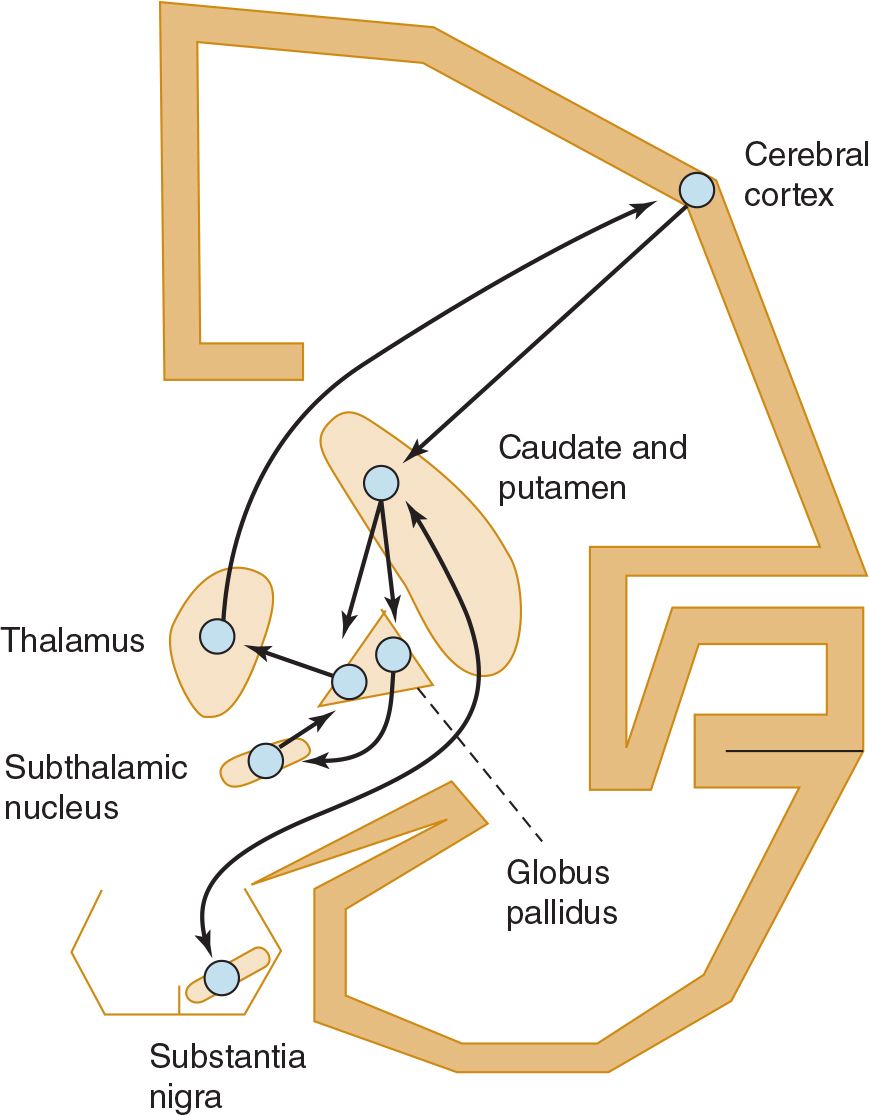

The basic circuitry of the basal ganglia consists of three interacting neuronal loops (Figure 11-1). The first is a corticocortical loop that passes from the cerebral cortex, through the caudate and putamen, the internal segment of the globus pallidus, and the thalamus and then back to the cerebral cortex. The second is a nigrostriatal loop connecting the substantia nigra with the caudate and putamen. The third, a striatopallidal loop, projects from the caudate and putamen to the external segment of the globus pallidus, then to the subthalamic nucleus, and finally to the internal segment of the globus pallidus. In some movement disorders (eg, Parkinson disease), a discrete site of pathology within these pathways can be identified; in other cases (eg, essential tremor), the precise anatomic abnormality is unknown.

![]() Figure 11-1. Basic neuronal circuitry of the basal ganglia.

Figure 11-1. Basic neuronal circuitry of the basal ganglia.

TYPES OF ABNORMAL MOVEMENTS

Categorizing an abnormal movement is generally the first step toward arriving at the neurologic diagnosis. Abnormal movements can be classified as tremor, chorea, athetosis or dystonia, ballismus, myoclonus, or tics. They can arise in a variety of contexts, such as in degenerative disorders or with structural lesions. In many disorders, abnormal movements are the sole clinical features.

TREMOR

A tremor is a rhythmic oscillatory movement best characterized by its relationship to voluntary motor activity, that is, according to whether it occurs at rest, during maintenance of a particular posture, or during movement. The major causes of tremor are listed in Table 11-1. Tremor is enhanced by emotional stress and disappears during sleep. Tremor that occurs when the limb is at rest is generally referred to as static tremor or rest tremor. If present during sustained posture, it is called a postural tremor; although this tremor may continue during movement, movement does not increase its severity. When present during movement but not at rest, it is generally called an intention or kinetic tremor. Both postural and intention tremors are also called action tremors.

Table 11-1. Causes of Tremor.

Postural tremor

Physiologic tremor

Enhanced physiologic tremor

Anxiety or fear

Excessive physical activity or sleep deprivation

Sedative drug or alcohol withdrawal

Drug toxicity (eg, lithium, bronchodilators, sodium valproate, tricyclic antidepressants)

Heavy metal poisoning (eg, mercury, lead, arsenic)

Carbon monoxide poisoning

Thyrotoxicosis

Familial (autosomal dominant) or idiopathic (benign essential) tremor

Dystonic tremor

Cerebellar disorders

Wilson disease

Intention tremor

Brainstem or cerebellar disease

Drug toxicity (eg, alcohol, anticonvulsants, sedatives)

Wilson disease

Dystonic tremor

Rest tremor

Parkinsonism

Wilson disease

Heavy metal poisoning (eg, mercury)

Dystonic tremor

POSTURAL TREMOR

Physiologic Tremor

Physiologic Tremor

An 8- to 12-Hz tremor of the outstretched hands is a normal finding. Its physiologic basis is uncertain.

Enhanced Physiologic Tremor

Enhanced Physiologic Tremor

Physiologic tremor may be enhanced by fear or anxiety. A more conspicuous postural tremor may also be found after excessive physical activity or sleep deprivation. It can complicate treatment with certain drugs (notably lithium, tricyclic antidepressants, sodium valproate, and bronchodilators), is often conspicuous in patients with alcoholism or in alcohol or drug withdrawal states, and is common in thyrotoxicosis. It can also result from poisoning with a number of substances, including mercury, lead, arsenic, and carbon monoxide. There is no specific treatment.

Other Causes

Other Causes

The most common type of abnormal postural tremor is benign essential tremor, which may be familial. Postural tremor may be conspicuous in patients with Wilson disease or cerebellar disorders. A postural tremor of the hands that is indistinguishable from essential tremor may occur in patients with dystonia. The designation dystonic tremor refers to a postural or intention tremor that occurs in a part of the body already affected by dystonia. It is a part of the dystonia and is most prominent when an attempt is made to oppose the dystonic posturing.

ASTERIXIS

Asterixis may be associated with postural tremor, but is itself more properly considered a form of myoclonus (discussed later) than tremor. It is seen most commonly in patients with metabolic encephalopathy and resolves with clearing of the encephalopathy.

To detect asterixis, the patient holds the arms outstretched with fingers and wrists extended. Episodic cessation of muscular activity causes sudden flexion at the wrists followed by a return to extension, so that the hands flap in a regular or, more often, an irregular rhythm. A similar phenomenon may be demonstrable at the ankles.

INTENTION (KINETIC) TREMOR

Intention or kinetic tremor occurs during activity. If the patient is asked to touch his or her nose with a finger, for example, the arm exhibits tremor during movement, often more marked as the target is reached. This form of tremor is sometimes mistaken for limb ataxia, but the latter has no rhythmic oscillatory component.

Intention tremor results from a lesion affecting the superior cerebellar peduncle. Because it is often very coarse, it can lead to severe functional disability. No satisfactory medical treatment exists, but stereotactic surgery of the contralateral ventrolateral nucleus of the thalamus or high-frequency thalamic stimulation through an implanted device is sometimes helpful when patients are severely incapacitated.

Intention tremor can occur—with other signs of cerebellar involvement—as a manifestation of toxicity of certain sedative or anticonvulsant drugs (eg, phenytoin) or alcohol; it is also seen in patients with Wilson disease.

REST TREMOR

Parkinsonism

Parkinsonism

Rest tremor usually has a frequency of 4 to 6 Hz and is characteristic of parkinsonism whether the disorder is idiopathic or secondary (ie, postencephalitic, toxic, or drug induced in origin). The rate of the tremor, its relationship to activity, and the presence of rigidity or hypokinesia usually distinguish the tremor of parkinsonism from other forms of tremor. Tremor in the hands may appear as a “pill-rolling” maneuver—rhythmic, opposing circular movements of the thumb and index finger. There may be alternating flexion and extension of the fingers or hand or alternating pronation and supination of the forearm; in the feet, rhythmic alternating flexion and extension are common. Parkinsonism is discussed in more detail later.

Other Causes

Other Causes

Less common causes of rest tremor include Wilson disease and poisoning with heavy metals such as mercury.

CHOREA

The word chorea denotes rapid irregular muscle jerks that occur involuntarily and unpredictably in different parts of the body. In florid cases, the often forceful involuntary movements of the limbs and head and the accompanying facial grimacing and tongue movements are unmistakable. Voluntary movements may be distorted by superimposed involuntary ones. In mild cases, however, patients may exhibit no more than a persistent restlessness and clumsiness. Power is full, but there may be difficulty in maintaining muscular contraction such that, for example, handgrip is relaxed intermittently (milkmaid grasp). The gait becomes irregular and unsteady, with the patient suddenly dipping or lurching to one side or the other (dancing gait). Speech often becomes irregular in volume and tempo and may be explosive in character. In some patients, athetotic movements or dystonic posturing (see later) may also be prominent. Chorea disappears during sleep.

The pathologic basis of chorea is unclear, but some cases are associated with cell loss in the caudate nucleus and putamen. Dopaminergic drugs can provoke chorea. Causes of chorea are shown in Table 11-2 and are discussed later. When chorea is due to a treatable medical disorder, such as polycythemia vera or thyrotoxicosis, treatment of the primary disorder abolishes it.

Table 11-2. Causes of Chorea.

Hereditary

Huntington disease

Huntington disease-like (HDL) disorders

Dentatorubro-pallidoluysian atrophy

Benign hereditary chorea

Wilson disease

Paroxysmal choreoathetosis

Familial chorea with associated acanthocytosis

Static encephalopathy (cerebral palsy) acquired antenatally or perinatally (eg, from anoxia, hemorrhage, trauma, kernicterus)

Sydenham chorea

Chorea gravidarum

Drug toxicity

Levodopa and other dopaminergic drugs

Antipsychotic drugs

Lithium

Phenytoin

Oral contraceptives

Others (eg, anticholinergics, baclofen, carbamazepine, digoxin, felbamate, lamotrigine, valproate, certain recreational drugs)

Miscellaneous medical disorders

Thyrotoxicosis, hypoparathyroidism, Addison disease

Hypocalcemia, hypomagnesemia, hyponatremia, hypernatremia

Hyperglycemia, hypoglycemia

Polycythemia vera

Hepatic cirrhosis

Systemic lupus erythematosus, primary antiphospholipid syndrome

Encephalitis or meningoencephalitis (various viruses including human immunodeficiency virus, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Borrelia burgdorferi, Treponema pallidum, Toxoplasma gondii, other organisms)

Paraneoplastic syndrome

Cerebrovascular disorders

Vasculitis

Ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke

Subdural hematoma

Structural lesions of the subthalamic nucleus

HEMIBALLISMUS

Hemiballismus is unilateral chorea that is especially violent because the proximal muscles of the limbs are involved. It is due most often to vascular disease in the contralateral subthalamic nucleus and commonly resolves spontaneously in the weeks after its onset. It is sometimes due to other types of structural disease; in the past, it was an occasional complication of thalamotomy. Pharmacologic treatment is similar to that for chorea (discussed later).

DYSTONIA & ATHETOSIS

The term athetosis generally denotes abnormal movements that are slow, sinuous, and writhing in character. When the movements are so sustained that they are better regarded as abnormal postures, the term dystonia is used, and many now use the terms interchangeably. In dystonia, excessive or inappropriate contraction of muscles (often agonists and antagonists) leads to sustained abnormal postures of the affected region of the body. The abnormal movements and postures may be generalized (involving the trunk and at least two other sites) or restricted in distribution, such as to the neck (torticollis), hand and forearm (writer’s cramp), or mouth (oromandibular dystonia). With restricted dystonias, two or more contiguous body regions (eg, upper and lower face) may be affected (segmental dystonia), or the disturbance may be limited to localized muscle groups so that only a single body region is involved (focal dystonia). By international consensus, dystonia is now classified along a clinical axis (that includes age at onset, body distribution, temporal pattern, and associated features such as other movement disorders or neurologic features) and an etiologic axis that includes nervous system pathology and inheritance. Dystonia may be isolated (ie, occurring without other neurologic symptoms and signs apart from tremor) or secondary (Table 11-3), in which case other clinical features are present.

Table 11-3. Causes of Dystonia and Athetosis.

Inherited dystonias

Autosomal dominantly inherited disorders

Isolated generalized torsion dystonia and formes frustes

Huntington disease

Myoclonic dystonia

Dystonia-parkinsonism

Dopa-responsive dystonia

Dentatorubral-pallidoluysian atrophy

Neuroferritinopathy (neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation 3: NBIA3)

Spinocerebellar degenerations

Autosomal or X-linked recessively inherited disorders

Neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation 1

Lubag

Chorea-acanthocytosis

Lysomal storage disorders (eg, Pelizaeus-Merzbacher disease, Krabbe disease, metachromatic leukodystrophy)

Mitochondrionopathies

Leber hereditary optic atrophy

Acquired dystonias

Static perinatal encephalopathy (cerebral palsy)

Parkinson disease

Progressive supranuclear palsy

Wilson disease

Drugs

Levodopa and dopamine agonists

Antipsychotic drugs

Anticonvulsants

Calcium-channel blockers

Serotonin reuptake inhibitors

Others (see text)

Toxins (eg, methanol, manganese, carbon monoxide, carbon disulphide)

Infections: viral, postviral, bacterial, other

Vascular: ischemic anoxia; hemorrhage

Neoplastic disease

Psychogenic

FACTORS INFLUENCING DYSTONIA

The abnormal movements are not present during sleep. They are generally enhanced by emotional stress and by voluntary activity. In some cases, abnormal movements or postures occur only during voluntary activity and sometimes only during specific activities such as writing, speaking, or chewing.

ETIOLOGY

Table 11-3 lists some of the conditions in which these movement disorders are encountered. Perinatal anoxia, birth trauma, and kernicterus from hyperbilirubinemia are the most common causes. In these circumstances, abnormal movements usually develop before 5 years of age. Careful questioning usually discloses a history of abnormal early development and often of seizures. Examination may reveal signs of cognitive dysfunction or a pyramidal deficit in addition to the movement disorder.

Dystonic movements and postures are the cardinal features of isolated torsion dystonia (discussed later). Torsion dystonia may also occur as a manifestation of Wilson disease or Huntington disease or as a sequela of encephalitis.

Acute dystonic posturing may result from treatment with dopamine receptor antagonist drugs (discussed later).

Lateralized dystonia may occasionally relate to focal intracranial disease, but the clinical context in which it occurs usually identifies the underlying cause.

MYOCLONUS

Myoclonic jerks are sudden, rapid, twitchlike muscle contractions. They can be classified according to their distribution, relationship to precipitating stimuli, site of origin (Table 11-4), or etiology. Generalized myoclonus has a widespread distribution, whereas focal or segmental myoclonus is restricted to a particular part of the body. Myoclonus can be spontaneous, or it can be brought on by sensory stimulation, arousal, or the initiation of movement (action myoclonus). Myoclonus may occur as a normal phenomenon (physiologic myoclonus) in healthy persons, as an isolated abnormality (essential myoclonus), or as a manifestation of epilepsy (epileptic myoclonus). It can also occur as a feature of a variety of degenerative, infectious, and metabolic disorders (symptomatic myoclonus) affecting the cerebral cortex, brainstem, or spinal cord. Myoclonus is sometimes manifest not by a sudden twitchlike muscle contraction but by a sudden loss of muscle activity (negative myoclonus). This is best seen as asterixis, discussed earlier. Careful clinical evaluation—noting the age of onset, character, and distribution of myoclonus, precipitating stimuli and relieving factors, family history, and presence of any associated symptoms and signs—may suggest the cause and limit unnecessary investigations.

Table 11-4. Anatomic Origin of Myoclonus.

Cortical

Cerebral anoxia (Lance-Adam syndrome)

Metabolic and toxic disorders (eg, uremia, dialysis syndrome, lithium, levodopa)

Neurodegenerative, infective, traumatic, vascular, and neoplastic diseases involving the cerebral cortex (eg, Alzheimer disease, Jakob-Creutzfeldt disease, Parkinson disease, and Parkinson-plus syndromes)

Epilepsies and epilepsia partialis continua

Cortical reflex myoclonus

Subcortical and brainstem

Exaggerated startle (eg, hereditary, static encephalopathies, brainstem encephalitis, multiple sclerosis, paraneoplastic disorders)

Essential, myoclonus-dystonia, and ballistic overflow myoclonus (hereditary or sporadic)

Reticular reflex myoclonus (caudal brainstem lesions; eg, uremia, posthypoxic)

Palatal myoclonus (dentate-olivary lesions)

Spinal

Propriospinal myoclonus (eg, trauma, tumor, idiopathic)

Segmental myoclonus (eg, trauma, infective, inflammatory, tumor, compressive, vascular lesions, idiopathic)

Peripheral

Hemifacial spasm (microvascular compression, tumor, inflammatory)

Peripheral nerve or plexus injury (physical injury, tumor)

Psychogenic

GENERALIZED MYOCLONUS

Causes are summarized in Table 11-5. Physiologic myoclonus includes the myoclonus that occurs upon falling asleep or awakening (nocturnal myoclonus) as well as hiccup. Essential myoclonus is a benign condition that occurs in the absence of other neurologic abnormalities and is sometimes inherited. Epileptic myoclonus may be impossible to differentiate clinically from nonepileptic forms. They may be distinguished electrophysiologically, however, by the duration of the electromyographic burst associated with the jerking, by demonstrating an electroencephalographic (EEG) correlate related temporally to the jerks, or by determining whether muscles involved in the same jerk are activated synchronously.

Table 11-5. Causes of Myoclonus.

Physiologic myoclonus

Nocturnal myoclonus

Hiccup

Essential myoclonus (hereditary or sporadic)

Epileptic myoclonus

Symptomatic myoclonus

Degenerative disorders

Storage diseases (eg, Lafora body disease, lipidoses, ceroid-lipofuscinosis)

Pantothenate kinase-associated neurodegeneration

Wilson disease

Huntington disease

Myoclonus dystonia

Alzheimer disease

Parkinson disease and Parkinson-plus disorders

Spinocerebellar degenerations

Infectious disorders

Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease

HIV-associated dementia

Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis

Viral encephalitis

Whipple disease

Metabolic disorders

Drug intoxications (eg, penicillin, antidepressants, bismuth, levodopa, anticonvulsants)

Drug withdrawal (ethanol, sedatives)

Hypoglycemia

Hyperosmolar nonketotic hyperglycemia

Hyponatremia

Hepatic encephalopathy

Uremia, dialysis syndrome

Hypoxia (Lance-Adams syndrome)

Focal brain or nerve damage

Head injury

Stroke

Tumors

Peripheral nerve or plexus injury (physical injury, tumor)

FOCAL OR SEGMENTAL MYOCLONUS

Focal or segmental myoclonus can arise from lesions affecting the cerebral cortex, brainstem, spinal cord, or peripheral nerve. It can result from many of the same disturbances that produce symptomatic generalized myoclonus (see Table 11-5). Metabolic disorders such as hyperosmolar nonketotic hyperglycemia can cause epilepsia partialis continua, in which a repetitive focal epileptic discharge occurs from the contralateral sensorimotor cortex and leads to segmental myoclonus. Brainstem involvement of the dentatorubroolivary pathway by stroke, multiple sclerosis, tumors, or other disorders can produce palatal myoclonus, which may be associated with an audible click or synchronous movements of ocular, facial, or other bulbar muscles. Rhythmic vertical oscillation of the soft palate occurs that is best regarded as a tremor. An irritative lesion of a peripheral or cranial nerve may lead to myoclonus, as exemplified by hemifacial spasm (discussed in Chapter 9, Motor Disorders). Segmental myoclonus is usually unaffected by external stimuli and persists during sleep.

PROPRIOSPINAL MYOCLONUS

Propriospinal myoclonus arises in the spinal cord and then spreads up and down the cord, leading to a brief bodily contraction. Electromyographic surface recordings may be necessary to show the spread of muscle activity in an orderly sequence and may help to localize the site of origin of the myoclonus. The underlying spinal lesion may be revealed by imaging in some cases.

TREATMENT

Although myoclonus can be difficult to treat, cortical myoclonus in particular sometimes responds to anticonvulsant drugs such as valproic acid 250 to 500 mg orally three times daily or levetiracetam titrated up to 500 to 1,500 mg orally twice daily. It may also respond to piracetam (not available in the United States). Benzodiazepines such as clonazepam 0.5 mg orally three times daily, gradually increased to as much as 12 mg/d may help all types of myoclonus. A combination of medications is often necessary. Postanoxic action myoclonus is remarkably responsive to 5-hydroxytryptophan, the precursor of the neurotransmitter 5-hydroxytryptamine (serotonin). The 5-hydroxytryptophan is increased gradually to a maximum of 1 to 1.5 mg/d orally and may be combined with carbidopa (maximum, 400 mg/d orally) to inhibit metabolism in peripheral tissues. Localized myoclonus, regardless of origin, may respond to botulinum toxin injections. A variety of other medications have been used to treat different types of myoclonus, including carbamazepine, primidone, topiramate, zonisamide, diazepam, and—for essential myoclonus—anticholinergic agents, with anecdotal reports of benefit.

TICS

Tics are sudden, recurrent, quick, coordinated abnormal movements that can usually be imitated without difficulty. The same movement occurs repeatedly and can be suppressed voluntarily for short periods, although doing so may cause anxiety. Tics tend to worsen with stress, diminish during voluntary activity or mental concentration, and disappear during sleep.

CLASSIFICATION

Tics can be classified into four groups depending on whether they are simple or multiple and transient or chronic.

1. Transient simple tics are common in children, usually terminate spontaneously within 1 year (often within a few weeks), and generally require no treatment.

2. Chronic simple tics can develop at any age but often begin in childhood, and treatment is unnecessary in most cases. The benign nature of the disorder must be explained to the patient.

3. Persistent simple or multiple tics of childhood or adolescence generally begin before 15 years of age. There may be single or multiple motor tics, and often vocal tics, but complete remission occurs by the end of adolescence.

4. The syndrome of chronic multiple motor and vocal tics is generally referred to as Gilles de la Tourette syndrome, after the French physician who described its clinical features. It is discussed in detail later. Tics also may occur with levodopa or amphetamine use and after chronic neuroleptic use (tardive tic), after head trauma or viral encephalitis, and in autistic children. They can occur in association with degenerative disorders of the basal ganglia, such as Huntington disease, and are well described in neuroacanthocytosis, when they may have a self-mutilating character.

BRADYKINESIA & HYPOKINESIA

Bradykinesia (slowed movement) and hypokinesia or akinesia (poverty or lack of movement) are major features of parkinsonism and may be quite disabling. Manifestations include a fixity of facial expression (the so-called masked facies, with reduced blinking, widened palpebral fissures, and an apparently impassive appearance) and a paucity of spontaneous movement of the limbs (eg, a reduced arm swing on walking). Some patients have “freezing,” that is, a temporary inability to move. Such symptoms are difficult for patients to describe and are often attributed erroneously to weakness.

These phenomena are tested clinically by, for example, asking the patient to make repetitive alternating movements of each extremity in turn. This can involve tapping of the index or third finger on the pad of the thumb, pronation and supination of the raised arm (as if screwing a light bulb into the ceiling), opening and closing of the fist, stomping with the foot on the ground, and tapping the foot on the floor while the heel is maintained on the ground. A progressive reduction in amplitude or speed of the movements, irregularity in rhythm, or arrests in movement indicate abnormality. Activity should be continued until at least 15 repetitions have occurred, and sometimes for longer. Abnormalities must be distinguished from the slowness of movement without fatiguing and decrement that may occur in patients with pyramidal or cerebellar dysfunction (often with an irregular rhythm in the latter context). The inexpressive face of depressed patients may simulate the masked facies of parkinsonism and should be distinguished by the lack of other extrapyramidal findings and the abnormal affect.

CLINICAL EVALUATION OF PATIENTS

HISTORY

AGE AT ONSET

The age at onset of a movement disorder may suggest the underlying cause. For example, onset in infancy or early childhood suggests birth trauma, kernicterus, cerebral anoxia, or an inherited disorder; abnormal facial movements developing in childhood are more likely to represent tics than other involuntary movements; and tremor presenting in early adult life is more likely to be of the benign essential variety than due to Parkinson disease.

The age at onset can also influence the prognosis. In isolated torsion dystonia, for example, progression to severe disability is much more common when symptoms develop in childhood rather than later life. Conversely, tardive dyskinesia is more likely to be permanent and irreversible when it develops in the elderly than during adolescence.

MODE OF ONSET

Abrupt onset of dystonic posturing in a child or young adult suggests a drug-induced reaction; a more gradual onset in an adolescent suggests a chronic disorder such as isolated torsion dystonia or Wilson disease. Similarly, the abrupt onset of severe chorea or ballismus suggests a vascular cause, and abrupt onset of severe parkinsonism suggests a neurotoxic cause; more gradual, insidious onset suggests a degenerative process.

COURSE

The manner of progression from onset may also be helpful diagnostically. For example, Sydenham chorea usually resolves within about 6 months after onset and therefore should not be confused with other varieties of chorea that occur in childhood.

MEDICAL HISTORY

Drug History

Drug History

An accurate account of all drugs taken by the patient over the years is important, because many movement disorders are iatrogenic. Neuroleptic drugs may lead to abnormal movements developing either while patients are taking them or after their use has been discontinued, and the dyskinesia may be irreversible, as discussed later.

Reversible dyskinesia may develop in patients taking certain other drugs, including oral contraceptives, levodopa, and phenytoin. Several drugs, especially lithium, tricyclic antidepressants, valproic acid, and bronchodilators, can cause tremor. Serotonin reuptake inhibitors have been associated with a number of movement disorders including parkinsonism, akathisia, chorea, dystonia, and bruxism.

General Medical History

General Medical History

1. Chorea may be symptomatic of rheumatic fever, thyroid disease, systemic lupus erythematosus, polycythemia, hypoparathyroidism, or cirrhosis of the liver.

2. Movement disorders, including tremor, chorea, hemiballismus, dystonia, and myoclonus, may occur in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). Opportunistic infections such as cerebral toxoplasmosis or cryptococcosis are often responsible, and infection with human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) may also have a direct pathogenic role.

3. A history of birth trauma or perinatal distress may suggest the cause of a movement disorder that develops during childhood.

4. Encephalitis lethargica, epidemic in the 1920s, was often followed by a wide variety of movement disorders, including parkinsonism. Various other viral encephalitides (Japanese encephalitis, West Nile, St Louis, herpes simplex, dengue, mumps, measles) may be accompanied or followed by movement disorders.

Family History

Family History

Some movement disorders have an inherited basis and a complete family history must be obtained, supplemented if possible by personal scrutiny of close relatives. Any possibility of consanguinity should be noted.

EXAMINATION

Clinical examination indicates the nature of the abnormal movements, the extent of neurologic involvement, and the presence of coexisting disease; these in turn may suggest the diagnosis.

Psychiatric illness or cognitive impairment raises the possibility that the movement disorder is related to that or its treatment with psychoactive medication—or that the patient has a disorder with both abnormal movements and behavioral disturbances, such as Huntington disease or Wilson disease.

Focal motor or sensory deficits raise the possibility of a structural space-occupying lesion, as does papilledema. Kayser-Fleischer rings suggest Wilson disease. Signs of vascular, hepatic, or metabolic disease may suggest other causes for a movement disorder, such as acquired hepatocerebral degeneration or vasculitis.

INVESTIGATIVE STUDIES

BLOOD & URINE TESTS

1. Serum and urine copper and serum ceruloplasmin levels are important in diagnosing Wilson disease.

2. Complete blood count and sedimentation rate are helpful in excluding polycythemia, vasculitis, or systemic lupus erythematosus, any of which can occasionally lead to a movement disorder. A wet film of the blood may reveal circulating acanthocytes.

3. Blood chemistries may reveal hepatic dysfunction related to Wilson disease or acquired hepatocerebral degeneration; hyperthyroidism or hypocalcemia as a cause of chorea; or a variety of metabolic disorders associated with myoclonus.

4. Serologic tests are helpful for diagnosing movement disorders caused by systemic lupus erythematosus or lupus anticoagulant syndrome. Neurosyphilis and HIV-1 infection should always be excluded by appropriate serologic tests in patients with neurologic disease of uncertain etiology.

ELECTROPHYSIOLOGIC TESTS

An EEG may help in evaluating myoclonus and in distinguishing paroxysmal dyskinesias from seizures; otherwise, it is of limited usefulness. Electromyography and somatosensory evoked potentials may help to determine the level of neural involvement in myoclonus.

IMAGING

In some patients, intracranial calcification may be found by skull x-rays or computed tomography (CT) scans; the significance of this finding, however, is not always clear. CT scans or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may also reveal a tumor or other lesion associated with focal dyskinesia or dystonia or with symptomatic myoclonus, caudate atrophy due to Huntington disease, or basal ganglia abnormalities associated with Wilson disease. Positron emission tomography (PET) using 18F-dopa can monitor the loss of nigrostriatal projections in Parkinson disease and may be helpful diagnostically in patients with incomplete parkinsonian syndromes, but is not widely available. Dopamine transporter imaging using single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) can also be used for this purpose.

GENETIC STUDIES

Recombinant DNA technology has been used to generate probes for genes that determine certain inheritable movement disorders, such as Huntington disease and Wilson disease. Their use may be limited, however, by the genetic heterogeneity of some diseases, imprecise gene localization by certain probes, ethical concerns about adverse psychologic reactions to the presymptomatic diagnosis of fatal disorders, and the potential for misuse of such information by prospective employers, insurance companies, and government agencies.

PSYCHOLOGIC EVALUATION

Cognitive and affective disturbances can be documented and characterized by neuropsychologic evaluation. This may be helpful in diagnosing certain disorders such as Huntington disease or diffuse Lewy body dementia. Some movement disorders, such as Gilles de la Tourette syndrome, are associated with behavioral abnormalities such as attention deficit disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder. The findings also may be important in guiding decisions regarding invasive interventions such as deep brain stimulation, which is contraindicated in patients with atypical parkinsonian syndromes or in classic Parkinson disease when significant dementia or major depression is also present.

SELECTED MOVEMENT DISORDERS

The more common and well-defined diseases or syndromes characterized by abnormal movements are discussed here together with the principles of their treatment.

FAMILIAL OR ESSENTIAL TREMOR

PATHOGENESIS

A postural tremor may be prominent in otherwise normal subjects. Although the pathophysiologic basis of this disorder is uncertain, it often has a familial basis with an autosomal dominant mode of inheritance. At least four gene loci have been implicated: three using linkage studies—hereditary essential tremor 1 (ETM1), ETM2, ETM3—and one using exome sequencing, ETM4; in some cases (ETM1), the disorder is related to a polymorphism in the D3 dopamine receptor gene (DRD3). There is evidence of involvement of olivocerebellar and cerebello-thalamo-cortical pathways. Decreased levels of GABAA and GABAB receptors have been found postmortem in the dentate nucleus. Patients with essential tremor have a higher risk of developing Parkinson disease than the general population.

CLINICAL FINDINGS

Symptoms may develop in the teenage or early adult years but often do not appear until later. The tremor typically involves one or both hands, the head, the voice, or some combination of these, but the legs tend to be spared. Examination usually reveals no other gross abnormalities, but some patients may have mild ataxia or personality disturbances. Although the tremor may increase with time, it often leads to little disability other than cosmetic and social embarrassment. In occasional cases, tremor interferes with the ability to perform fine or delicate tasks with the hands; handwriting is sometimes severely impaired. Speech is affected when the laryngeal muscles are involved. A small quantity of alcohol sometimes provides remarkable but transient relief; the mechanism is not known. The diagnosis is made on clinical grounds by the type of tremor and absence of other causes of tremor or neurologic abnormalities.

TREATMENT

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree