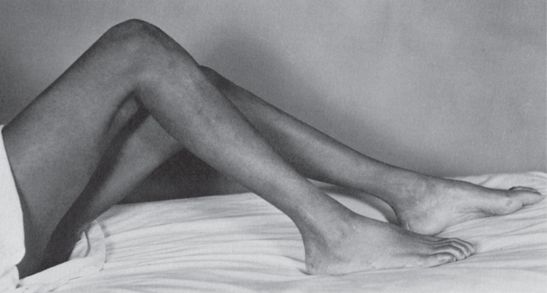

FIGURE 29.1 A patient with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis showing advanced atrophy of the muscles of the hands and shoulders.

Involvement of nerve roots, plexus elements, or peripheral nerves leads to atrophy of the muscles supplied by the diseased or injured component. With severe lesions involving a peripheral nerve or nerve plexus, atrophy may develop within a short period of time. Within 1 month after denervation, there may be a 30% loss of weight in the affected muscle and a 50% loss within 2 months; thereafter, the atrophy progresses more slowly and replacement by connective tissue and infiltration by fat follows. Lesions involving single nerve roots usually do not cause much atrophy, because most muscles are innervated from more than one level. Marked wasting in a disease that appears consistent with radiculopathy suggests multiple root involvement. In generalized peripheral neuropathy, weakness and wasting are usually greatest in the distal portions of the extremities. The amount of atrophy depends on the severity and chronicity of the neuropathy. The hereditary peripheral neuropathy, Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease (peroneal muscular atrophy), typically causes marked atrophy in a characteristic distribution involving the lower legs (inverted champagne bottle deformity, Figure 29.2).

FIGURE 29.2 A patient with Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease (peroneal muscular atrophy) showing wasting of distal muscles and contractures of the hands and feet.

The complete syndrome of peripheral nerve dysfunction, with paralysis, atrophy, sensory impairment, areflexia, and trophic changes in the skin and other tissues is the result of interruption of motor, sensory, and autonomic fibers. Interruption of sensory nerve fibers alone does not lead to muscular atrophy except as related to disuse, but loss of pain sensation may predispose one to painless injuries, including ulcerations following minor trauma and burns. The autonomic system is involved in trophic function by regulating the nutrition and metabolism of muscle and other tissues. Because of interruption of autonomic pathways, diseases of the lower motor neuron may be associated with trophic changes in the skin and subcutaneous tissues: edema, cyanosis or pallor, coldness, sweating, changes in the hair and nails, alterations in the texture of the skin, osteoporosis, and even ulcerations and decubiti. Autonomic fibers may be a factor in muscle atrophy because of “trophic dysfunction” and loss of vasomotor control.

Upper motor neuron lesions in adults are usually not followed by atrophy of the paralyzed muscles except for some generalized loss of muscle volume and secondary wasting because of disuse, which is seldom severe. With lesions dating from birth or early childhood, there may be a failure of growth of the contralateral body. Such congenital hemiatrophy may involve one side of the face or the face and corresponding half of the body; it is characterized by underdevelopment not only of the muscles but also of the skin, hair, subcutaneous tissues, connective tissue, cartilage, and bone. Congenital hemihypertrophy is rarer than the corresponding hemiatrophy, and there are usually other anomalies. There may be underdevelopment of one-half of the body due to either lack of development or atrophy of the opposite cerebral hemisphere (cerebral hemiatrophy). Severe cerebral insults in early life may lead to hemiplegia, hemiatrophy, partial or hemiseizures, and the development of delayed hemidystonia (“4-hemi” syndrome). Experimentally, lesions of the motor cortex and the descending corticospinal pathways may be followed by muscular atrophy, and on occasion, severe wasting appears with cerebral hemiplegias. The atrophy progresses rapidly if it appears early and slowly if it appears late. Usually, there are associated trophic and sensory changes, and the wasting may in part be secondary to involvement of the postcentral gyrus or parietal lobe, lesions of which are known to be followed by contralateral atrophy. The loss of muscle bulk associated with lesions of the parietal lobe may appear promptly; the degree of atrophy depends upon the size and character of the lesion and the extent of the hypotonia and sensory change. The distribution is determined by the localization of the process within the parietal lobe. It is most severe if the motor cortex or pathways are involved along with the sensory areas of the brain. Hemiatrophy may also complicate hemiparkinsonism. Rarely, hemiatrophy is idiopathic.

Other Varieties of Muscular Atrophy

Myogenic, or myopathic, atrophy occurs as a result of primary muscle disease. In some conditions, there may be prominent wasting without much weakness. In most of these, the primary pathologic change is type 2 fiber atrophy. Wasting with little weakness occurs in disuse, aging, cachexia, and some endocrine myopathies. Weakness out of proportion to wasting occurs in inflammatory myopathy, myasthenia gravis, and periodic paralysis.

Muscle wasting is common in muscular dystrophy, and the distribution of the wasting parallels the weakness. In dystrophinopathies, the weakness and atrophy primarily involve the pelvic and shoulder girdle muscles (Figure 29.3). As the disease progresses, there is increasing wasting of all muscles of the shoulders, upper arms, pelvis, and thighs. In the face of all of the atrophy, certain muscles—particularly the calf muscles—are paradoxically enlarged due to pseudohypertrophy. The limb-girdle syndromes also primarily involve the pelvic and shoulder girdles. In facioscapulohumeral (Landouzy-Dejerine) dystrophy, the atrophy predominates in the muscles of the face, shoulder girdles (especially the trapezius and periscapular muscles), and upper arms, especially the biceps (Figure 29.4). Involvement is often asymmetric, and occasionally, there is pseudohypertrophy of the deltoid and other shoulder muscles. Distal myopathies, affecting the muscles of the hands and feet, are occasionally seen. Wasting involving the distal extremities, with relative sparing of the hands and feet, is likely to be myopathic. In contrast, denervation atrophy involves the entire distal extremity, including the hand or foot. Some myopathies cause striking weakness and atrophy involving certain muscles or muscle groups. In myotonic dystrophy, there is prominent atrophy of the sternocleidomastoid muscles. Scapuloperoneal syndromes involve the periscapular and peroneal muscles. Selective involvement of the quadriceps occurs in inclusion body myositis and type 2B limb-girdle muscular dystrophy (dysferlin deficiency).

FIGURE 29.3 A patient with muscular dystrophy showing wasting of the musculature in the shoulders and thighs; weakness and atrophy of the glutei cause difficulty in assuming the erect position, and the patient “climbs up on his thighs” (Gowers maneuver) in order to stand erect.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree