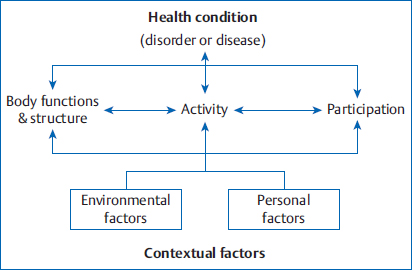

3 Neuro-Developmental Treatment Practice and the ICF Model The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) was developed by the World Health Organization to provide a common language with which to organize, label, and classify multiple health conditions. The ICF taxonomy is presented, and the implications for Neuro-Developmental Treatment (NDT) practice are discussed. The emphasis is on the particular problem-solving process within NDT practice that includes analysis of the relationships between the ICF domains and the contextual factors during information gathering, examination, evaluation, and intervention for clients with cerebral palsy or a traumatic brain injury or for those who have had a stroke. Learning Objectives Upon completing this chapter the reader will be able to do the following: • Describe, define, and give clinical examples of the components of the ICF. • Describe how an NDT practitioner will relate, analyze, and prioritize the components of the ICF model. • Apply the ICF model within the NDT Practice Model. • Analyze a plan of care for an individual with disabilities based on an NDT interpretation of the ICF model. The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health1,2 (ICF) is a framework that organizes, labels, and categorizes biological and social perspectives of health and disability. It was approved by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2002 and revised multiple times. It was developed as a complement to the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-10),2,3 a diagnostic tool that classifies diseases and other health problems. The ICF taxonomy describes the many facets of human functioning that may be affected by a health condition, as seen in Fig. 3.1. It provides a common language that permits comparisons of data across countries, health care disciplines, services, and time.2 The framework is a classification system and not a measurement system, although it is possible to identify the severity of each factor. The classification system explores health or disability within three different domains: social functions (participation or participation restriction), individual (activities or activity limitation), and body structure and function (integrities or impairments). The classification system considers domains as interactive and dynamic rather than linear and static. In addition, the ICF taxonomy includes contextual factors that are either facilitators (contribute to health, wellness, or functioning) or barriers (contribute to disability). The contextual factors take into account both the environmental impact as well as multiple personal factors that affect an individual’s ability to participate, affect functional activity, and affect the body structures and function themselves. In the ICF framework, functioning and disability are viewed as encompassing a complex interaction between the individual, the environment, and the health condition. Health and disability are seen in a different light, with these conditions appearing as an ever-changing continuum rather than as two separate distinct categories. An individual may display different degrees of functioning or disability across time or when one is considering different aspects of functioning. Therefore, the classification schema is applicable to all people because it does not address specific health conditions or diseases. The ICF model has also been modified to more adequately address the information in children and youth who are rapidly developing and demonstrating dramatic changes in physical, social, and psychological function. The ICF used for children and youth (ICF-CY)4,5,6 has been derived from the ICF to document the characteristics of children and youth in the first 2 decades of life. It now includes descriptions of functions that are more unique or particularly relevant to childhood, such as play. It omits descriptions that are not related to childhood or youth, such as menopause. Fig. 3.1 The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health model demonstrating the Health/Disability Continuum.1,2 Reproduced, with the permission of the publisher, Towards a Common Language for Functioning, Disability and Health: ICF, Geneva, World Health Organization, 2002 (http://www.who.int/classifications/icf/training/icfbeginnersguide.pdf, accessed September 8, 2014). Both the ICF and ICF-CY include the same three domains (social: participation and participation restriction; individual: activity and activity limitation; and body structure and function: integrities and impairments). Each domain is subdivided into chapters which are listed in the first column of Tables 3.1, 3.2, and 3.3. Participation reflects a person’s functional involvement in a life situation at any point in the life span. Participation restrictions, on the other hand, reflect problems that an individual may encounter in those same real-life situations, no matter what the cause. Function in the social domain includes the performance of an activity within a specific relevant environment or within a specific societal context, as seen in Table 3.1. Participation includes how the person functions in multiple environments and therefore considers all contextual factors. It is more likely to include multiple functional activities and sequences of those activities. It usually involves other people and is based on the person’s value systems or goals. It is related to the overall quality of life. Within the ICF model, each domain is subdivided into chapters that more clearly focus the attention. For adults, we look at participation as reflecting how individuals meet their expected social roles.7,8,9,10 It can include the roles in family life, including accepting roles within a nuclear and extended family, whether as a child in the family, a spouse in a young couple, a parent raising a child, or an adult caring for an aging parent. It also includes the roles related to education, both formal and informal, and work or employment. It includes descriptions of involvement in the community, such as in churches, community groups, and government and within the worldwide community. For a young child the social roles may initially appear less clear.11,12,13,14 However, there are still definite participations, even in infancy. In the first months, the infant is typically expected to be an active participant in home and family life. Initially, this participation may be as simple as sleeping when the rest of the family sleeps and eating when everyone else eats. With age, the expectation of participation increases to include playing with the parents and siblings, taking turns with others, waiting, and eventually taking on simple chores to improve the family’s overall quality of life. The roles gradually expand to include a wider expanded family and then a network of friends. The child begins to expand the roles learned in the family to include those outside the family. These participations extend to community settings as well as schools. The child may attend a day care center, mother’s-day-out program, or preschool. Most children start attending school and are expected to learn to play and to be part of larger groups, such as a class of 20 children, rather than as a member of a family only. For quite some time, these participations are led or supervised by an adult. However, before the age of 10 children begin to develop a network of friends and play without direct supervision or leadership of the adult. The child may play in the yard alone or with friends, with a parent checking in sporadically. They may have sleepovers with friends or visit the grandparents without the parents being present for short stays. This is the age where children join clubs with other peers in their age group, such as Boy Scouts, Rainbow Girls, or church groups. The ICF and ICF-CY use the term chapter to subdivide participation or participation restrictions.1,4 Clinical examples that might be encountered in clinical practice are described in the following section. A comprehensive clinical example of the social function domain and the chapters within it can be found in Case Report B8. Also look at Thieme MediaCenter for photo gallery. Brandon is a child diagnosed with cerebral palsy. He has a twin brother and a younger brother who also live at home with their parents and a half-sister. His life demonstrated the ever-changing shifts on the health well-ness/disability continuum in the social function domain. He was born at 25 weeks gestation and lived for 4 months in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), as did his twin. He was not able to participate in the typical home life of a newborn infant; rather, he required the support of an entire medical team. He was discharged from the NICU at 4 months of age and lived at home with his parents while his twin brother continued to be supported at the NICU. He developed increasing medical problems, had to return to the hospital, and was readmitted to the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) for an additional month and a half. Once he returned home he began fuller participation in family life. As a young infant Brandon lived at home, although he and his twin brother had separate rooms to accommodate the medical equipment necessary for Brandon’s care. He attended a school in his community for his pre-school and early elementary years, although he attended a self-contained class for children with severe cognitive impairments. He therefore demonstrated participation in that he attended the same school as his brother, yet he had participation restrictions because he could not ride the same school bus as his friends or attend classes with his neighborhood peers. He could not participate in play in his neighborhood. He did not develop friendships outside of his family. As his health diminished across the early years, he could no longer attend classes but was provided home-bound education. He could continue to participate in public education, but his participation restrictions now included that his education was provided in his own home with a teacher, but without the interaction of children or other teachers from the school. He no longer participated in bus rides, even on the school bus with a wheelchair lift. He did participate in outpatient therapy services and participated not only with a physical therapist (PT), occupational therapist (OT), and speech-language pathologist (SLP) but also observed those same services with his brother. He met other professionals who interacted with him and his family. He met other families, including children with special needs. He also met the children’s parents as well as their siblings, who functioned both typically and atypically. He had nursing care from a variety of adults and adjusted to new caregivers. The additional care allowed him to remain at home for as many years as feasible. As his respiratory difficulties and seizures increased, his participation restrictions continued to increase. Brandon had frequent hospitalizations that limited the opportunity to participate as fully in family life. In addition, Brandon had more frequent absences from therapies due to his illnesses.

3.1 The ICF Model of Health and Disability

3.1.1 Social Function (Participation and Participation Restriction)

Participation/Participation Restriction Case Report Example

Participation examples | Participation restriction | |

Learning and Applying Knowledge | Learns at age level at neighborhood school. | Must attend self-contained class with limited curriculum so graduates without high school diploma. |

General Tasks and Demands (undertaking single or multiple tasks) | Able to complete science project on time with all steps. | Unable to handle stress of moving to new school and meeting new teachers and peers, so elects homebound education. Forgets to pick up children at school because sidetracked at grocery store doing weekend shopping. |

Communication (communication with spoken and nonspoken messages, speaking and holding conversations, producing nonverbal messages | Able to communicate wants, concerns, and ideas with friends in setting without adults present. | Unable to tell stranger name or phone number when lost at the mall. |

Mobility (lifting and carrying objects, picking up and grasping objects, walking, moving around using equipment, using transportation, driving) | Able to move in crib to obtain pacifier to return to sleep at night. | Unable to walk across community playground and get on and off equipment. |

Self-Care (washing, toileting, dressing, eating, drinking, caring for body, and looking after own health) | Able to drink from cup provided by fast food restaurant while on family trip. | Unable to locate and put on coat and backpack at end of school day in time to catch bus to go home. |

Domestic Life (housework, acquisition of goods and services, assisting others) | Able to load and unload dishwasher after dinner without request as chore for the good of the family. | Unable to help younger sibling with homework while parent prepares dinner. |

Interpersonal Interactions and Relationships (basic and complex interactions, relating with strangers, formal relationship family relationships, intimate relationships) | Able to be calmed by staffat day care setting in addition to being calmed by both parents. | Does not have any friends outside of the immediate family. |

Major Life Areas (formal and informal education, employment, economic self-sufficiency) | Able to attend neighborhood school in regular classroom setting. | Unable to learn rules of simple childhood games, so excluded from playing with others at recess. |

Community, Social, and Civic Life (community, recreation and leisure, religion and spirituality, human rights, political life and citizenship) | Able to attend YMCA summer camp program with friends. | Unable to participate in community soccer league because walker is not permitted on field of play. |

If one considers the habilitation/rehabilitation field, it is clear that a major role of therapists is to improve an individual’s ability to participate and to limit participation restrictions. Carey and Long15 outline a role of the therapist for advocating for and evaluating pediatric participation. There is, however, great diversity in participation in all individuals with neuromuscular disorders.7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14 Multiple factors impact the person’s participation, ranging from contextual factors, such as the family priorities,12 to the availability of assistive technology or adaptive equipment.16 In addition, the individual’s functional activity level is related. Those individuals who are more severely involved physically or with significant communication limitations are more likely to participate with individuals only within the family or within the home.9,11

3.1.2 Individual Function (Activities and Activity Limitations)

Activities1,3 describe an individual’s functioning as a whole person. They reflect the execution of a task or an action by a person. Activity is a person’s positive performance of a task, and activity limitation is the difficulty that the individual may have in executing that task. The tasks are more discrete in nature. This domain does, however, still include contextual factors in the description of the task. The concept includes the fact that performing a task in one setting can be very different from performing the same task in a different setting. For example, a person may be able to feed him- or herself a meal at home, but eating the same meal at a restaurant with a large group of the spouse’s coworkers may not be feasible. There are usually multiple activities that must be performed in complex and specific environments to allow participation. Outcome measures for both adults and children are being designed to specifically examine a client’s abilities to perform functional activities.17,18

The line between the social and individual domains is not, however, always distinct. A task at one point in life may be a focus for an individual, such as when a child learns to walk or when an adult first walks with a cane after a stroke. The activity may have such relevance and value to the family that it is viewed as participation. The child who has learned to walk may no longer have to be carried by an adult and therefore moves freely through the yard for play. Or the adult who is able to walk 50 feet with a cane can be discharged from the inpatient rehabilitation facility. However, later this same skill may become only one activity in a more complex participation, such as walking from the classroom to the school bus while carrying books and talking with friends, or cleaning the house, including vacuuming, dusting, and putting away household items in appropriate cabinets.

This individual function domain includes the entire spectrum of activities and activity limitations, as seen in Table 3.2. The chapters for activities are the same as those listed under the participation domain.

Activity/Activity Limitation Case Report Example

In Dennis’s case report (A6) in Unit V, the therapist looked initially at reports from him and his wife concerning what he could do and what he could not do. This information was supplemented by the therapist’s observation during sessions. Initially, Dennis and his wife reported the he was able to move in bed independently but slowly. Dennis provided much of the information to the therapist, so he was able to communicate with others verbally.

Activity | Activity limitation | |

Learning and Applying Knowledge | Able to label items in environment, such as “ball,” “book,” “car.” | Unable to learn multiplication tables. |

General tasks and Demands | Able to finish homework independently. | Unable to turn on IPad and select correct icon for desired game. |

Communication | Able to call parent loudly enough to be heard from another room. | Unable to be understood by an unfamiliar person. |

Mobility | Able to get in and out of bed. | Unable to ascend or descend stairs. |

Self-Care | Able to “go potty” when requested. | Unable to put on a T-shirt. |

Domestic Life | Able to clean up room. | Unable to open food packages. |

Interpersonal Interactions and Relationships | Able to play with a same-aged peer for 5 minutes without adult intervention. | Unable to initiate play with unfamiliar but same aged peer. |

Major Life Area | Able to play independently for 10 minutes. | Unable to ride bicycle independently. |

Community, Social, and Civic Life | Able to play a game with family. | Unable to sit through church service without being disruptive. |

Dennis’s goals were to return to work and to be able to walk, ride his bike, and travel again. He and his wife were also planning to be able to spend more time after retirement with their grandchildren who lived nearby. The therapist in the case report reveals how these goals related to desired participation and activities of the client, his current activities, and activity limitation level to shape long-term and short-term outcomes for therapy, as well as including these valued activities within intervention sessions.

3.1.3 Body Function and Structures (Integrities and Impairments)

The third domain in the ICF model considers the functioning of systems within the body itself. Body structures are anatomical parts of the body, including the organs, limbs, and trunk and their components. Body functions1,3 are the physiological and psychological functions of body systems. The functioning/health end of the continuum in this domain is referred to as integrities, and the disease or disability end of the continuum is labeled as impairments. Body structure impairments are problems in structure seen as a significant deviation or loss. Impairments of body structures or function are the inability of body parts or organs to function typically.

The system integrities and impairments can be linked to a single system, such as a deficit in the auditory system, or may be linked to multiple systems, such as poor balance, which may include the interaction of deficits in the visual and vestibular systems as well as limited axial strength and decreased spinal mobility in the musculoskeletal system, and a deficit in the timing and sequencing of muscle activation reflecting deficits in the neuromuscular system. Once again within the ICF model, the body functions and structure are divided into nine chapters. In this domain the chapters have a specific organ or system focus.

• Mental functions related to the nervous system structure.

• Sensory and pain functions related to sensory structures such as the eyes or ears.

• Voice and speech functions related to the structures of voice and speech.

• Functions of the cardiovascular, hematological, immunological, and respiratory systems based on the structures of the cardiovascular system, the immunological system and the respiratory system.

• Functions of the digestive, metabolic, and endocrine systems based on those structures.

• Functions of the genitourinary and reproductive systems based on those structures.

• Functions of the neuromuscular system and movement-related functions based on the structures related to movement.

• Functions of the skin and related structures and the structures of the skin and related structures.

In evaluating an individual for health care intervention, it is important to be able to identify specific body structure and function abilities (integrities) and impairments, as seen in Table 3.3.

Table 3.3 Body structure and function integrities and impairments with examples across the life span

Chapter | Integrity | Impairment |

Mental functions | Behaves appropriately in different settings, demonstrating executive function. | Short attention span. |

Sensory and pain functions | Two-point discrimination abilities. | Poor midline orientation. |

Voice and speech functions | Articulates with voice loud enough to be heard across room. | Dysarthria. |

Cardiovascular, hematological, immunological respiratory systems | Energy Expenditure Index is age appropriate. | Blood pressure drops when in upright postures. |

Digestive, metabolic, and endocrine systems | Eats regular diet. | Reflux after each meal. |

Genitourinary and reproductive systems | Controls bladder for toileting. | No menstrual cycle occurs. |

Skin and related structures | Skin and fascia heal rapidly after surgery. | Skin breakdown over both ischial tuberosities. |

Neuromuscular system–and movement-related functions | Good single-leg standing balance Full passive range of motion (PROM) | Inability to recruit postural motor units. Weakness of scapular adducto rs or depressors. |

3.1.4 Contextual Factors

ICF and ICF-CY models also include the impact of contextual factors1,4 on each domain. These contextual factors can be identified as either facilitators or barriers according to the impact on the individual. The contextual factors include environmental influences as well as personal factors as seen in Fig. 3.1 previously in this chapter.

Environmental factors are those features of the physical, social, and attitudinal world that create the backdrop of an individual’s life. The environmental factors could include scene-setting factors, such as the climate or culture, and can change the opportunities or imperatives for the individual’s involvement in the participation domain. Examples of these environmental factors could include a region’s job market or the family’s economic status. They could also include a family’s religious beliefs, a teacher or boss’s perspective on inclusion of individuals with disabilities in standard environments, or a given culture’s perspective on the importance of play. It could include immediate environmental factors, such as the family home, school, or work setting, and potential living environments, such as group homes or nursing homes. They could also include the availability and use of assistive technology, such as the type of AFO selected, the particular walker that is ordered, the availability of an augmentative communication device, or even the clothing that the individual wears.

The personal factors1,3 are divided into three proposed categories that include scene setting personal factors, potentially modifiable personal factors, and social relationships. Some of these factors include simple identifying factors, such as gender, age, height, weight, or educational background. Personal factors can also include more complex factors, such as personal goals and motivations, the ability to cope with changes or learn new motor tasks, the ability to deal with frustration, or a knowledge base pertaining to general health or the condition a person is facing. The contextual factors influence all activities and all body structures and functions and are also a major link to participation or participation restrictions.

3.1.5 Interaction of Concepts

The ICF model treats the domains as interactive and dynamic. Domains are not viewed as being linear or causative in nature. The ICF model shifts the focus from a disease- or condition-based approach to one based on varying levels of functioning. Therefore, practitioners should no longer plan care for the “right hemiplegic” or even for the “child with diplegia” but instead should plan to meet the desired outcomes within each domain based on the individual’s status at a given moment in time.

The ICF model is integrated into all aspects of health care. In evaluation and diagnosis, individuals may be classified within each domain rather than receiving only a global diagnosis based on pathology. In terms of a therapist’s examination, standardized tests are being developed and evaluated based on each of the different domains. For example, there has been a shift from tests that considered generalized developmental milestones to tests that now focus on participation and activities or that specifically test a single body structure or function, such as testing muscle strength, range of motion, blood pressure, or respiratory rate.17,18 There are also separate tests that look at balance, gait pattern, or the swallowing mechanism. The overall outcomes from therapy are viewed as targeting improved participation or activities with supporting objectives targeting body structure and function. Intervention strategies are developed and implemented to address each domain specifically. Interventions are then evaluated based on how they influence that specific domain. Franki19,20 specifically reported on the effectiveness of Neuro-Developmental Treatment (NDT) on each of the domains within the ICF model.

This individualized intervention planning is at the heart of NDT. The ICF model provides a compatible framework with consistent vocabulary to discuss NDT practice. However, to understand the NDT Practice Model it is necessary to delve further into the ICF model from the perspective of the NDT philosophy, theoretical assumptions, and principles as presented previously in the first two chapters of this unit.

3.2 The ICF Model from an NDT Perspective

NDT practitioners recognize that they work within a large health care environment and an even larger global environment. A key to successful integration of NDT is clear communication among therapists, health care practitioners, researchers, outside governmental agencies, and international groups that regulate or influence the provision of health care to individuals in all practice settings across the life span. Although the ICF framework is very effective in providing consistency in vocabulary, it was not designed to describe how the different domains are related to each other.

In NDT practice, the clinician looks very specifically and carefully at each domain and the relationships among the domains presented in the ICF model. Hypotheses about these relationships are made during information gathering, examination, evaluation, and intervention planning, and within every intervention session. The NDT clinician also looks at the body structure and function domain and further discriminates general issues of posture and movement (multisystem functions) from issues of single-system function. In addition, the therapist carefully analyzes the impact of the environmental and personal contextual factors on each of the domains.

The ICF model does not suggest to a clinician how to help an individual to reach desired activity outcomes or how to improve a client’s participation. It does not aid the clinician in developing an intervention plan. This clinical decision-making process is what the NDT Practice Model does (see Chapter 5). NDT describes, explains, and demonstrates the relationships of the domains and the processes of clinical decision making.

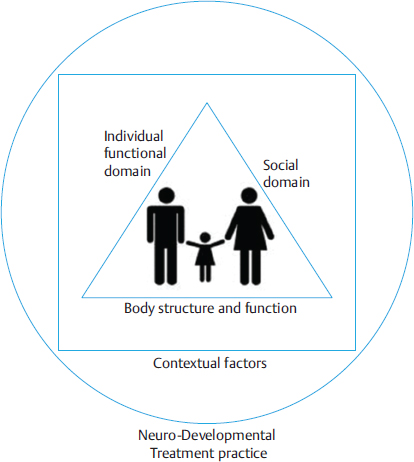

In the NDT philosophy it is clear that the individual is at the center of the entire information gathering, examination, and evaluation process, as seen in Fig. 3.2. The task of organizing all of the information can be challenging, however, for the clinician to develop a plan of care that is most effective. The ICF model can be helpful in organizing all of the observations. The clinician moves from getting to know the individual to categorizing information into the different domains.

When using the NDT Practice Model the therapist moves outward in the schematic seen in Fig. 3.2 to considering the three sides of the triangle. Initially, the therapist gathers information about the social and individual functioning domains, noting specific examples of the participations/participation restrictions and activities/activity limitations that are reported and observed, as seen on two sides of the triangle. The examination then moves to the more detailed review of the bottom line of the triangle, that of the body structures and functions. The participation/restrictions and activities/limitations are viewed as growing out of the underlying body structure and function integrities and impairments. Yet they also interact and lead to changes in body structure and function status. No side of the triangle exists in isolation of the other two sides. The examination and intervention is thus always based on the ongoing interaction of these three elements.

The NDT practitioner then moves further outward in the problem-solving process as seen in the square of Fig. 3.2 to consider the influence of the contextual factors on each of the domains individually and also on the interactive group (the triangle). The contextual factors include both the personal factors and the environmental factors.

The practice of NDT then is represented as the circle because it encompasses how the therapist gathers, examines, observes, handles, evaluates, and prioritizes information, and then intervenes, within all the domain and contextual factors for each individual. The remainder of this chapter focuses on a more detailed review of this process as a foundational model of NDT that will then be expanded in the remaining chapters of the book.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree