Onset: acute, subacute, and insidious

Preceding symptoms: headache, vertigo, vision or hearing complaints, focal neurologic findings, fever, and signs of systemic illness

Environment: recent trauma, access to toxins or medications

Medical history: medical problems (epilepsy), medications

Mental Status: Eyes open or closed? Responds or regards? Follows any commands?

Cranial Nerves: Blink to threat (CN II). Reactivity of pupils (CN III). Spontaneous eye movements or tracking (CN III, IV, VI). Corneal reflexes (CN V, VII). Oculocephalic reflex, assuming no cervical trauma (CN VIII, III, VI). Gag (CN IX, X, XII).

Motor: Asymmetries in tone or spontaneous movements. Response to noxious stimuli with localizing, withdrawal, or posturing. Asymmetries in reflexes.

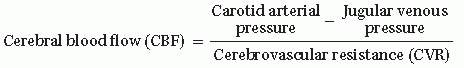

physiology of cerebral perfusion and brain oxygenation, followed by general pathophysiology.

TABLE 13.1 Neuromonitoring in the ICU | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

CPP = Mean arterial pressure (MAP) – Intracranial pressure (ICP)

MAP = 2/3 Diastolic pressure (DP) + 1/3 Systolic pressure (SP)

MAP = DP + 1/3 (SP – DP)

Therefore, increases in blood pressure lead to increases in CPP and increases in ICP lead to decreases in CPP

Normal range for CPP is age dependent since MAP increases with age while ICP remains mostly unchanged (Table 13.2; note that these values vary slightly based on gender and height)

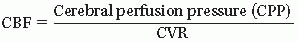

Cerebral vasculature mechanisms to maintain CPP (Fig. 13.1)

Metabolic mechanisms based on plasma osmolality

Neural mechanisms can be intrinsic and extrinsic

Intrinsic: Autoregulation (A, Fig. 13.1)

occur with dysfunctions of ventricular shunts and their valves (ventriculosubgaleal, ventriculoperitoneal, ventriculoatrial, and ventriculopleural shunts).

FIGURE 13.1 Cerebral Vasculature Mechanisms to Maintain Cerebral Perfusion Pressure (CPP). Cerebral blood flow (CBF) = CPP over cerebral vascular resistance (CVR). With a MAP 50 to 150 mm Hg in older children and adults (lower range in infants and younger children). Autoregulation maintains stable CBF with changes in CVR. (Adapted with permission from Westover MB, Choi E, Awad KM, et al., eds. Pocket Neurology. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins; 2010:46-47.) |

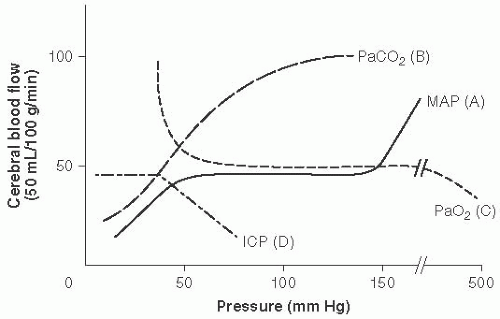

The cranial vault contains:

Brain parenchyma, 80%; blood, 10%; CSF, 10%.

The amount of CSF ˜150 mL, with 500 mL made daily (about 20 mL/h).

In adults and older children the ICP is generally between 11 and 28 cm H2O or 8 to 20 mm Hg, although this range decreases with age2 (see Table 13.2).

Any increase in brain parenchyma, blood, or CSF can produce changes in mechanical forces and may lead to herniation (Fig. 13.2).

Both cytotoxic and vasogenic mechanisms can lead to cerebral edema.

Cytotoxic edema is caused by cellular injury that leads to excitatory amino acid release, leading to cell depolarization and sodium traveling into the cell, causing swelling.

Vasogenic edema is the result of dysfunctional vessels, such as those of a tumor, which allow passage of intravascular fluid into the interstitial space.

to cause brain contusions, focal injuries, and coup-contrecoup injuries. Rotational injuries occur in motor vehicle accidents and sports injuries, and nonaccidental trauma leads to shearing forces causing traumatic axonal injury occurring in white matter fiber tracts. All of these injuries lead to increased excitatory neurotransmission and neurometabolic cascades, leading to axonal injury and cell death.4 Furthermore, children’s brains seem to be more susceptible to cerebral swelling following head injury as compared with those of adults.5

|

FIGURE 13.2 Types of Brain Herniation. 1. Uncal: ipsilateral CN III palsy and contralateral hemiplegia or posturing. 2. Central transtentorial: coma with bilateral small pupils and progression of posturing from decorticate to decerebrate with loss of brainstem reflexes. 3. Subfalcine: coma and contralateral weakness to posturing. 4. Extracranial (when craniectomy is present): deficits from herniated territory. 5. Upward cerebellar: cerebellar symptoms to coma and bilateral posturing. 6. Tonsillar (downward cerebellar): decreased arousal, pyramidal signs, respiratory insufficiency, coma. (Adapted with permission from Westover MB, Choi E, Awad KM, et al., eds. Pocket Neurology. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2010:46-47.) |

Noncontrast head CT remains the best neuroimaging modality for quickly assessing for bony abnormalities, hemorrhage, and swelling.

MRI will be more sensitive for ischemia and subtler structural abnormalities.

Lab testing should be focused on assessing for cause of the injury (urine toxicology) and systemic injury (e.g., liver and renal function).

Osm 300-360

Measure BP (MAP). Goals: Maintain CPP (see Table 13.2)

PaCO2 35-40

ultimately Ca2+ influx into the cells, leading to cell necrosis and apoptosis. Additionally, creation of free radicals, accumulation of toxic by-products, and local inflammatory response, as well as reperfusion injury contribute to cell necrosis and death.20

TABLE 13.3 Treatment of Increased Intracranial Pressure (ICP) | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|